Q: “Dr. Smith, do you have an opinion, to a reasonable degree of medical certainty, as to the cause of 6-month-old baby Johnson’s condition when he arrived at the City Hospital at 4 am on November 23?”

A: “Yes, I do have an opinion.”

Q: “What is that opinion?”

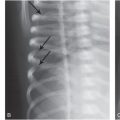

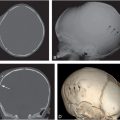

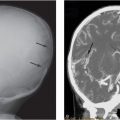

A: “My opinion is that the recent injuries, i.e., a metaphyseal fracture and several rib fractures suffered by the child, were due to abuse.”

Q: “Dr. Smith, would you please explain to the Court the reasons for your opinion that the metaphyseal fracture and rib fractures of Baby Johnson, which you believe to be 7 to 14 days old as of November 23, were due to abuse?”

You would then begin to discuss specifically how certain of the foundation evidence you have already testified to was specific for child abuse: e.g., that the location and nature of the metaphyseal corner fracture and the rib fractures were highly specific for infant abuse and not accidental injury (Box 26.2).

Q: “Doctor, are there any other reasons that you believe the 7- to 14-day-old injuries you found on November 23 were due to abuse and not accidental?”

A: “Yes. The previous injuries, one occurring sometime in early October and yet another sometime in August, are metaphyseal corner fractures characteristic of abuse and not accident. Additionally, the presence of a previous rib fracture at the costovertebral junction is highly indicative of previous abuse. Both the type and the repetitive nature of injuries is highly specific for abuse.”

You would then explain the reasons why the type and location of the rib fractures, in conjunction with the other injuries and the history given, contributed to your opinion that the injuries suffered by the six-month-old baby were due to abuse and not to accident. It is extremely helpful and very persuasive if you are able to demonstrate the likely mechanics of the infliction of such trauma at this time. This is where a demonstration, either with a doll or with charts, would assist the jury in understanding your opinion.

If counsel has learned of before the trial or anticipates a defense of genetic causation in addition to “accident,” you may be asked in the course of your direct testimony if you considered other possibilities to explain the child’s condition. You might offer an opinion that the baby’s condition is not as a result of, for example, osteogenisis imperfecta, and say that you have ruled out that differential diagnosis, even though there were no clinical or other reasons to suspect that the baby had a genetic disorder. (This area might be left to re-direct questioning, after defendant’s counsel has cross-examined you.)

Cross-examination

It is unlikely that you will be attacked on your “credibility”; i.e., counsel is not likely to suggest you are fabricating intentionally, but rather will seek to limit the authority the jury may give to your opinion. Cross-examination by opposing counsel will generally seek to show the jury that your testimony, especially your opinion, is flawed or qualified in some way and entitled to little or no weight in the jury’s deliberations. The cross-examiner may try to undercut your experience or knowledge in the particular area at issue; he or she may seek to show that even though your opinion sounds authoritative, the actual reason(s) underpinning your conclusions is/are inaccurate or incomplete, or that current research and studies, if not proving you wrong, may suggest a reasonable doubt about your conclusions. Indeed, as discussed above, challenging the science underpinning SBS/AHT has been fertile ground for defense counsel. However, the particular strategy will vary and may depend on whether the defense will offer its own expert at trial.

Assume that skillful cross-examiners will have done their homework on the subject matter at hand as well as on your own qualifications, and will attempt to expose any weaknesses or gaps in the testimony you have just given. They may focus on the lack of experience or publication you have in the particular area on which you are offering an opinion. (This will more likely to happen if defense offers an expert witness whose credentials, they may believe, are more impressive.) They may attack the completeness of the number or type of studies or procedures actually performed or the completeness of documentation of the studies or procedures that were done.

If your records are incomplete or unclear, it may provide fodder to the attorney to attack the soundness and reliability of your opinion even if your oral testimony is clear and convincing. If you have not reviewed all the existing relevant documents, especially if you are a consulting expert, counsel will attack the reliability of an opinion based on an incomplete review of data. Sound preparation to ensure the thoroughness of your foundation evidence and your opinion testimony is the best defense for this kind of attack on your reliability.

The cross-examination may focus on attempting to establish that there are other possible theories to explain the child’s condition: e.g., that the injuries could have been the result of accident or of a genetic disorder such as osteogenesis imperfecta, or both. You should be prepared to explain the nature of possible differential diagnoses, their manifestations, and why they are not a plausible explanation for the condition of the child in the case at trial. You should be aware of current journal articles or publications, which may be the subject of questioning.

Counsel may also attack you as a “hired gun,” especially if he or she can show? that you always testify for the same “side.” Again, this is less likely to happen if the defense offers its own expert witness. You can be impeached if you have written or spoken in the past about the issues in a manner that contradicts your current testimony. Do not underestimate the extent to which a computer database makes readily available newspaper articles, oral addresses, or lectures you may have given in the past.

You should listen carefully to each question asked by the cross-examiner, but do not worry excessively about why it was asked. Be aware that defense counsel may attempt to seek your agreement to a series of seemingly harmless or irrelevant statements, and if so, consider if you need to qualify your answer with “it depends on the context … .” However, it is not your job at the trial to play lawyer.

Cross-examination questions may also be objectionable; if an objection is made, you should wait for the Court’s ruling before you answer. Occasionally, although the direct examination or cross-examination question may not be objected to, counsel may move for an answer to be struck from the trial record if it offers irrelevant, privileged, or otherwise inadmissible testimony. The jury will be told by the judge to disregard any material that is struck, as if it were never spoken and they never heard it.

Distinguish questions that call for speculation and to which you cannot know the answer from those questions to which you do not know the answer or cannot remember the answer. On cross-examination, as in direct examination, you may suggest that your memory would be refreshed by a review of documents.

Never argue with opposing counsel; try to be neutral when responding to the cross-examiner’s tone of voice or type of questions, particularly if he or she appears to be harassing or attacking. To some extent, counsel and the judge will keep control over the opposing counsel, but you should remain disengaged. Do not get angry or defensive; it will color your judgment and your response to questions and will impair your ability to effectively “teach” the judge or jury. In fact, be cooperative. This does not include volunteering material not asked for, but you should pay attention to each question and make your best effort to answer it.

How does the questioner mechanically attempt to impeach your testimony in all the ways discussed above? Most effective cross-examiners will seek to control your testimony by asking questions to which you must answer “yes” or “no”: e.g., “Do you agree with me, Doctor, that many children under the age of two suffer from skeletal fractures as a result of accidents?” If you cannot answer any question truthfully “yes” or “no,” you should not hesitate to say so. If you have made a mistake or if it appears that you have said something you did not wish to say, you should so indicate, once the question before you is complete, and by correcting or clarifying your answer. You should do this even if you realize your error after you have made the statement and you have progressed to answering other questions. You are entitled to request to clarify an answer or a previous answer if it appears you misspoke or you misunderstood the question. The judge may instruct you that this can be done in your re-direct examination.

Re-direct examination

After cross-examination, the direct examiner has a brief period to try to “rehabilitate” you or clarify your testimony if he or she feels that you did not get a chance to answer completely or that opposing counsel has undercut the impact of your opinion in some way. Questions on re-direct examinations are usually limited by the judge to areas of inquiry pursued in or raised by cross-examination. Usually, only good pre-trial preparation and anticipation of areas likely to be the subject of cross-examination will allow you to be effective in the re-direct portion of your testimony.

Sequestration

You will ordinarily be excused from the courtroom after your testimony if there is a sequestration order. The order also means you cannot discuss with any other witnesses or potential witnesses the contents of your testimony or theirs. The exception is noted above; for some expert testimony, the judge will allow an expert to view certain portions of the trial by the parties’ agreement or by order of the Court.

Conclusion

As soon as you begin to evaluate imaging studies, you are potentially a witness in some form of legal proceeding. If you keep this in mind from the beginning, the process of testifying should be easier and your testimony is more likely to be helpful. Testifying is not a “test” of your memory or character, although it may seem so. It is a slow, often painstaking (and unscientific!) way to try to provide information. As television, computers, smartphones, and other electronic devices make the sending and receiving of information almost instantaneous, the old-fashioned method of question and answer can seem laborious and frustrating. However, every direct examination and every cross-examination question presumably has a purpose. You have been called to testify because you are knowledgeable and have relevant and material information to share. Understanding the process and your role in it should help you become a more productive participant.