Neoplasms |

Metastatic tumor

Fig. 10.40 |

Single or multiple, well-circumscribed or poorly defined lesions involving the vertebral marrow, dura, and/or leptomeninges; low to intermediate attenuation; usually with contrast enhancement, with or without bone destruction, with or without pathologic vertebral fracture, with or without compression of neural tissue or vessels. Leptomeningeal tumor often best seen on postcontrast images. |

Metastatic tumor may have variable destructive or infiltrative changes involving single or multiple sites of involvement. |

Lymphoma

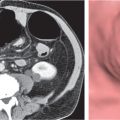

Fig. 10.41a–c |

Single or multiple well-circumscribed or poorly defined infiltrative lesions involving the vertebrae, epidural soft tissues, dura, and/or leptomeninges; low to intermediate attenuation; usually with contrast enhancement, with or without bone destruction. Diffuse involvement of vertebra with Hodgkin lymphoma can produce an “ivory” vertebra. Leptomeningeal tumor often best seen on postcontrast images. |

Lymphoma may have variable destructive or infiltrative marrow/bony changes involving single or multiple vertebral sites. Lymphoma may extend from bone into adjacent soft tissues within or outside the spinal canal or initially involve only the epidural soft tissues or only the subarachnoid compartment. Can occur at any age (peak incidence third to fifth decades). |

Myeloma/plasmacytoma

Fig. 10.42a, b |

Multiple (myeloma) or single (plasmacytoma), well- circumscribed or poorly defined diffuse infiltrative lesions involving the vertebra (e), and dura; involvement of vertebral body typical; rarely involves posterior elements until late stages, low to intermediate attenuation, usually with contrast enhancement, with bone destruction. |

Myeloma may have variable destructive or infiltrative changes involving the axial and/or appendicular skeleton. |

Osteosarcoma

Fig. 10.43a, b |

Destructive malignant lesions, usually with matrix miner-alization/ossification within lesion or within extraosseous tumor extension; can show contrast enhancement (usually heterogeneous). Cortical bone destruction and epidural extension of tumor can compress the spinal canal and spinal cord. |

Malignant bone lesions rarely occur as primary tumor involving the vertebral column, locally invasive, high metastatic potential. Occurs in children as primary tumors and adults (associated with Paget disease, irradiated bone, chronic osteomyelitis, osteoblastoma, giant cell tumor, and fibrous dysplasia). |

Chordoma

Fig. 10.44a–d |

Well-circumscribed, lobulated radiolucent lesions, low to intermediate attenuation; usually shows contrast enhancement (usually heterogeneous); locally invasive associated with bone erosion/destruction; usually involves the dorsal portion of the vertebral body with extension toward the spinal canal. Also occurs in sacrum. |

Rare, slow-growing, destructive notochordal tumors (~3% of bone tumors); usually occur in adults 30 to 70 y; M > F (2:1); sacrum (50%) > skull base (35%) > vertebrae (15%). |

Chondrosarcoma

Fig. 10.45a–c |

Lobulated radiolucent lesions, low to intermediate attenuation, with or without matrix mineralization; may show contrast enhancement (usually heterogeneous); locally invasive associated with bone erosion/destruction, encasement of vessels and nerves; can involve any portion of the vertebra. |

Rare, slow-growing, malignant cartilaginous tumors (~16% of bone tumors), usually occur in adults (peak in fifth to sixth decades), M > F; sporadic (75%), malignant degeneration/transformation of other cartilaginous lesion enchondroma, osteochondroma, etc. (25%). |

Aneurysmal bone cyst

Fig. 10.46a, b |

Circumscribed vertebral lesion usually involving the posterior elements with or without involvement of the vertebral body; with variable low, intermediate, high, and/or mixed attenuation, with or without surrounding thin shell of bone, with or without lobulations, with or without one or multiple fluid–fluid levels, with or without pathologic fracture. |

Expansile blood/debris filled lesions that may be primary or occur secondary to other bone lesions, such as giant cell tumor, fibrous dysplasia, and chondroblastoma. Most occur in patients younger than 30 y. Locations: lumbar > cervical > thoracic. Clinical findings can include neurologic deficits and pain. |

Hemangioma

Fig. 10.47a–d |

Circumscribed or diffuse vertebral lesion, usually radiolucent–destruction of bone trabeculae, located in the vertebral body with or without extension into pedicle or isolated within pedicle; typically low to intermediate attenuation with thickened vertical trabeculae; can show contrast enhancement; multiple in 30%. Location: thoracic (60%) > lumbar (30%) > cervical (10%). Occasionally, lesions extend from bone into the epidural soft tissues. |

Most common benign lesions involving vertebral column, F > M; composed of endothelial-lined capillary and cavernous spaces within marrow associated with thickened vertical trabeculae and decreased secondary trabeculae; seen in 11% of autopsies. Usually asymptomatic; rarely cause bone expansion and epidural extension resulting in neural compression (usually in thoracic region); increased potential for fracture with epidural hematoma. |

Osteochondroma

Fig. 10.48 |

Circumscribed sessile or protuberant osseous lesion typically arising from posterior elements of vertebrae, central zone contiguous with medullary space of bone, with or without cartilaginous cap. Increased malignant potential when cartilaginous cap is > 2 cm thick. |

Benign cartilaginous tumors arising from defect at periphery of growth plate during bone formation with resultant bone outgrowth covered by a cartilaginous cap. Usually benign lesions unless associated with pain and increasing size of cartilaginous cap. Can occur as multiple lesions (hereditary exostoses) with increased malignant potential. |

Paget disease

Fig. 10.49a, b |

Expansile sclerotic/lytic process involving a single or multiple vertebrae with mixed intermediate to high attenuation. Irregular/indistinct borders between marrow cortical bone; can also result in diffuse sclerosis, “ivory” vertebral pattern. |

Chronic disease with disordered bone resorption and woven bone formation. Usually seen in older adults, polyostotic in 66%; can result in narrowing of neuroforamina and spinal canal. |

Melorheostosis

Fig. 10.50a, b |

Attenuation of these lesions is based on the relative proportions of chondroid, mineralized osteoid, and soft tissue components. Mineralized zones typically have high attenuation along sites of thickened cortical bone; typically no contrast enhancement is seen in bone lesions. Nonmineralized portions can have low to intermediate attenuation and can show contrast enhancement. |

Rare bone dysplasia with cortical thickening that has a “flowing candle wax” configuration. Associated soft tissue masses occur in ~25%. The soft tissue lesions often contain mixtures of chondroid material, mineralized osteoid, and fibrovascular tissue. Surgery is usually performed only for lesions causing symptoms. |

Neoplasms and other masses |

Schwannoma (neurinoma) |

Circumscribed or lobulated extramedullary lesions, intermediate attenuation, with contrast enhancement. Contrast enhancement can be heterogeneous in large lesions due to cystic degeneration and/or hemorrhage. |

Encapsulated neoplasms arising asymmetrically from nerve sheath; most common type of intradural extramedullary neoplasm; usual presentation in adults with pain and radiculopathy, paresthesias, and lower extremity weakness. Multiple schwannomas seen with NF2. |

Neurofibroma |

Lobulated extramedullary lesions with or without irregular margins, with or without extradural extension of lesion with dumbbell shape, intermediate attenuation, with contrast enhancement. Contrast enhancement can be heterogeneous in large lesions; with or without erosion of foramina, with or without scalloping of dorsal margin of vertebral body (chronic erosion or dural ectasia/NF1). |

Unencapsulated neoplasms involving nerve and nerve sheath; common type of intradural extramedullary neoplasm often with extra-dural extension; usual presentation in adults with pain and radiculopathy, paresthesias, and lower extremity weakness. Multiple neurofibromas seen with NF1. |

Hemangiopericytoma |

Extra- or intradural extramedullary lesions; can involve vertebral marrow, often well circumscribed, intermediate attenuation, with contrast enhancement (may resemble meningiomas), with or without associated erosive bone changes. |

Rare neoplasms in young adults (M > F) sometimes referred to as angioblastic meningioma or meningeal hemangiopericytoma; arise from vascular cells/pericytes; frequency of metastases > meningiomas. |

Arachnoid cyst |

Well-circumscribed intradural extramedullary lesions with low attenuation similar to CSF, no contrast enhancement; with or without associated erosive bone changes. |

Nonneoplastic congenital, developmental, or acquired extra-axial lesions filled with CSF; usually mild mass effect on adjacent spinal cord or nerve roots. |

Teratoma |

Circumscribed lesions with variable low, intermediate, and/or high attenuation; with or without contrast enhancement. May contain calcifications and cysts, as well as fatty components that can cause chemical meningitis if ruptured. |

Second most common type of germ cell tumors; occurs in children, M > F; benign or malignant types; composed of derivatives of ectoderm, mesoderm, and/or endoderm. |

Disk herniation |

Preoperative

Fig. 10.51

Fig. 10.52a, b

Fig. 10.53a, b

Fig. 10.54a, b |

Disk herniation/protrusion: Disk herniation in which the head of the protruding disk is equal in size to the neck on sagittal reconstructed images; disk herniation usually similar in attenuation to disk of origin.

Can be midline in position, off-midline in lateral recess, posterolateral within intervertebral foramen, lateral or anterior; with or without compression or displacement of thecal sac and/or nerve roots in lateral recess and/or foramen. |

Type of disk herniation (focal > broad-based) that results from inner annular disruption or subtotal annular disruption with extension of nucleus pulposus toward annular weakening/disruption with expansive deformation. |

|

Disk herniation/extrusion: Disk herniation in which the head of the disk herniation is larger than the neck on sagittal reconstructed images; attenuation of disk herniation usually similar to disk of origin.

Can be midline, off-midline in lateral recess, posterolateral within intervertebral foramen, lateral, or anterior. Can extend superiorly, inferiorly, or both directions; with or without associated epidural hematoma; with or without compression or displacement of thecal sac and/or nerve roots in lateral recess and/or foramen. Can be calcified or contain gas if originating from a disk with vacuum phenomenon.

Disk herniation/extruded disk fragment: Disk herniation that is not in contiguity with disk of origin, attenuation of disk herniation usually similar to disk of origin. Can be midline, off-midline in lateral recess, posterolateral within intervertebral foramen, lateral, or anterior. Can extend superiorly, inferiorly, or both directions. Rarely extend into dorsal portion of spinal canal or into thecal sac; with or without associated epidural hematoma; with or without compression or displacement of thecal sac and/or nerve roots in lateral recess and/or foramen. |

Type of disk herniation (focal > broad-based) with extension of nucleus pulposus through zone of annular disruption with expansive deformation.

Herniated fragment of nucleus pulposus without connection to disk of origin. |

Postoperative edema, scar/granulation tissue |

Postdiskectomy changes: Soft tissue material located in anterior epidural space with intermediate attenuation; with or without mass effect on thecal sac resulting from edema and tissue injury from surgery; with or without contrast enhancement; changes progressively involute after 2 months. |

Changes from diskectomy evolve from localized edema with or without hematoma with mass effect on the thecal sac during the immediate postoperative period to granulation tissue and scar (peridural fibrosis), which may show contrast enhancement usually without associated mass effect, with or without retraction of adjacent structures. |

Degenerative changes |

Posterior disk bulge/osteophyte complex

Fig. 10.55a–c |

Diffuse broad-based bulge of disk usually with accompanying osteophytes from the adjacent vertebral bodies. Disks usually have decreased heights, low to intermediate attenuation related to disk degeneration and desiccation of the nucleus pulposus; with or without vacuum disk phenomenon. |

With aging, altered disk metabolism, trauma, or biomechanical overload; the proteoglycan content in a disk can decrease resulting in disk desiccation, loss of turgor pressure in the disk, decreased disk height, bulging of the anulus fibrosus, with or without spinal canal stenosis, with or without narrowing of the intervertebral foramina, with or without thickening of spinal ligaments. |

Degenerative facet hypertrophy

Fig. 10.56a, b |

Hypertrophic degenerative facets indent the dorsal lateral margins of the thecal sac and can result in spinal canal stenosis. |

Degenerative arthritic changes involving the facet joints often lead to facet hypertrophy, which can result in spinal canal stenosis, usually in association with posterior disk bulge/osteophyte complexes. |

Ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (PLL)

Fig. 10.57a, b |

Occurs as midline ossification at the dorsal aspects of the disks and vertebral bodies over several levels. A thin radiolucent line may be seen between the PLL and dorsal vertebral body margin secondary to connective tissue between the nonossified inner layer and ossified outer layers of the PLL. |

The PLL extends from the C2 level to the sacrum and is attached to the anulus fibrosus of the disks and dorsal margins of the vertebral bodies. Ossification of the outer fibers of the PLL consists of lamellar bone and calcified cartilage, involves the cervical spine in 70%, thoracic in 15%, and lumbar region in 15%. Can result in spinal canal stenosis. |

Synovial cyst

Fig. 10.58a, b |

Circumscribed structure located adjacent to the medial aspect of a degenerated facet joint, thin rim of intermediate attenuation surrounding a central zone that can have low or intermediate attenuation. Typically no contrast enhancement centrally. |

Represents protrusion of synovium with fluid (ganglion cyst) from degenerated facet joint into spinal canal; variable MRI signal related to contents that may include mucinous or serous fluid, blood, hemosiderin, or air. |

Fracture fragments

Fig. 10.59a, b |

Acute/subacute fractures have sharply angulated cortical margins, no destructive changes at cortical margins of fractured end plates; with or without convex outward angulated configuration of compressed vertebral bodies, with or without spinal cord and/or spinal canal compression related to fracture deformity, with or without retropulsed bone fragments into spinal canal, with or without subluxation, with or without kyphosis, with or without epidural hematoma. |

Vertebral fractures can result from trauma, primary bone tumors/lesions, metastatic disease, bone infarcts (steroids, chemotherapy, and radiation treatment), osteoporosis, osteomalacia, metabolic (calcium/phosphate) disorders, vitamin deficiencies, Paget disease, and genetic disorders (osteogenesis imperfecta, etc.). |

Epidural hematoma |

Epidural collection with variable low, intermediate, and/or slightly high attenuation, with or without spinal cord compression. |

Attenuation of epidural hematomas can vary secondary to stage of blood clotting and hematocrit. Older epidural hematomas can have mixed attenuation related to the various states of hemoglobin and breakdown products. Can be spontaneous or result from trauma or complication from coagulopathy, lumbar puncture, myelography, or surgery. |

Spondylolysis

Fig. 10.60a, b |

Spondylolisthesis associated with cortical discontinuity of one or both pars interarticularis regions. |

Fractures of the pars interarticularis regions from traumatic or stress injuries can lead to spondylolisthesis with narrowing of the spinal canal and/or neural foramina. |

Epidural abscess

Fig. 10.61a, b |

Epidural collection with low signal attenuation surrounded by a peripheral rim (thin or thick) of contrast enhancement, with or without associated vertebral osteomyelitis/diskitis, with or without air collections, often extend over two to four vertebral segments; can result in compression of spinal cord and spinal canal contents. |

Epidural abscess can evolve from an inflammatory phlegmonous epidural mass, extension from paravertebral inflammatory process or vertebral osteomyelitis/diskitis. May be associated with complications from surgery, epidural anesthesia, diabetes, distant source of infection, immunocompromised status. Organisms commonly involved include S. aureus, gram-negative bacteria, tuberculosis, coccidioidomycosis, candidiasis, aspergillosis, and blastomycosis. Clinical findings include back and radicular pain, with or without paresthesias and paralysis of lower extremities. |

Epidural lipomatosis

Fig. 10.62 |

Increased extradural fat is seen within the spinal canal with resultant narrowing of the thecal sac. |

Epidural lipomatosis is a condition in which there is prominent deposition of unencapsulated mature adipose tissue in the epidural space. May be related to obesity, chronic use of steroid medication, or endogenous hyper-cortisolemia. Thoracic 60%, lumbar 40%. |

Inflammation/infection |

Rheumatoid arthritis

Fig. 10.63a, b |

Erosions of vertebral end plates, spinous processes, and uncovertebral and apophyseal joints. Irregular enlarged synovium (pannus: intermediate attenuation) at atlantodens articulation results in erosions of dens and transverse ligament, with or without destruction of transverse ligament with C1 on C2 subluxation and neural compromise, with or without basilar impression. |

Most common type of inflammatory arthropathy that results in synovitis, causing destructive/erosive changes of cartilage, ligaments, and bone. Cervical spine involvement seen in two thirds of patients, juvenile and adult types. |

Eosinophilic granuloma

Fig. 10.64a, b |

Single or multiple, circumscribed soft tissue lesions in the vertebral body marrow associated with focal bony destruction/erosion with extension into the adjacent soft tissues. Lesions usually involve the vertebral body and not the posterior elements, with low to intermediate attenuation, with or without contrast enhancement, with or without enhancement of the adjacent dura. Progression of lesion can lead to vertebra plana (a collapsed flattened vertebral body), with minimal or no kyphosis and relatively normalsized adjacent disks. |

Single lesion: Commonly seen in male patients younger than 20 y; proliferation of histiocytes in medullary cavity with localized destruction of bone with extension into adjacent soft tissues.

Multiple lesions: Associated with syndromes such as Letterer–Siwe disease (lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly), children younger than 2 y; Hand–Schüller–Christian disease (lymphadenopathy, exophthalmos, diabetes insipidus), children 5 to 10 y old. |

Gout |

Radiographic features may include erosions at the diskovertebral junctions or facet joints, osteophytes, spinal deformities with subluxations and pathologic fractures. Soft tissue swelling with or without calcifications can be seen with tophi that occur in the late phases of gout. Tophi often have 160 HU, which may be used for narrowing the differential diagnosis with respect to other joint diseases. |

Inflammatory disease involving synovium resulting from deposition of monosodium urate crystals. Occurs when the serum urate level exceeds its solubility in various tissues and body fluid (> serum urate level of 7 mg/dL in men and 6 mg/dL in women). Can be a primary disorder of hyperuricemia resulting from inherited metabolic defects in purine metabolism or inherited abnormalities involving renal tubular secretion of urate. Primary gout accounts for up to 90% of cases in men. Secondary gout results from acquired metabolic alterations caused by medications (thiazide diuretics, alcohol, salicylates, and cyclosporine) that diminish renal excretion of uric acid salts. |

Calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease (CPDD)

Fig. 10.65a, b |

Radiographs and CT show chondrocalcinosis, which can be seen at the C1–odontoid articulation. At C1–C2, hypertrophy of synovium may occur, which can have low to intermediate attenuation containing calcifications seen with CT. |

CPDD is a common disorder usually seen in older adults in which there is deposition of calcium pyrophosphate crystals resulting in calcifications of hyaline and fibrocartilage; associated with cartilage degeneration, subchondral cysts, and osteophyte formation. Symptomatic CPDD is referred to as pseudogout because of overlapping clinical features with gout. Usually occurs in the knee, hip, shoulder, elbow, and wrist, rarely at the odontoid–C1 articulation. |