10 Infection and Inflammation

10.1 Introduction

Inflammatory conditions of both infectious and noninfectious origin can result in neurologic symptoms and have a variety of appearances on imaging. The appearances on imaging of some of these disorders are characteristic, whereas others can have nonspecific appearance requiring a differential diagnostic approach. In some instances, the ability to narrow the differential diagnosis can by itself aid in determining the appropriate treatment and/or additional diagnostic tests for an inflammatory condition. Familiarity with the laboratory profiles of CSF abnormalities in different infectious and inflammatory processes is important.

10.2 Infection

10.2.1 Meningitis

The most common infectious condition of the central nervous system (CNS) is meningitis. Meningitis is not a diagnosis based on imaging, and imaging is generally not indicated in this condition unless there are atypical features or focal neurologic deficits. Testing of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is the primary means of confirming the diagnosis of meningitis. In patients with known meningitis, there are two primary reasons why imaging may be performed. The first is to seek signs of a source of the infection, such as osseous erosion from the mastoid air cells or paranasal sinuses, and the second is to seek signs of an abscess. Although computed tomography (CT) can reveal signs of osseous dehiscence, an abscess is best seen on contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI).

On MRI, meningitis will appear as leptomeningeal enhancement, usually without any parenchymal signal abnormality. Leptomeningeal enhancement is most commonly evaluated on post contrast T1 W images, although post contrast fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images are especially sensitive to it. Contrast-enhanced CT is rarely indicated in meningitis, because in most situations a high-quality unenhanced CT scan will identify any extra-axial collections or parenchymal edema, and contrast-enhanced MRI is more sensitive than contrast-enhanced CT in identifying inflammation. Computed tomographic examination without and with contrast enhancement will double the radiation dose delivered to the patient while yielding only slightly more information than will unenhanced CT. Performing only a post-contrast CT scan will limit the ability to detect hemorrhage. Therefore, the preferred diagnostic evaluation in suspected meningitis would be an unenhanced CT scan and, if there are abnormalities or further clinical concern, subsequent MRI without and with contrast enhancement. Ultimately, it should be remembered that a lumbar puncture is the most important tool in diagnosing meningitis. This can also be associated with a callout to (s. Tab.). 1

Condition | Results |

Normal* | Protein 15 to 60 mg/100 mL of CSF, glucose 50 to 80 mg/100 mL, cell count 0 to 5 white cells, no red blood cells |

Bacterial meningitis | Elevated neutrophil count, decreased glucose concentration; protein concentration can be elevated |

Viral meningitis | Elevated lymphocyte count, normal to mildly decreased glucose concentration |

Noninfectious inflammatory process | Minimally elevated lymphocyte count, normal glucose concentration, mildly elevated protein concentration |

Neoplasm with cerebrospinal fluid dissemination | Markedly elevated protein concentration; perform cytology on cerebrospinal fluid sample if concern exists about possible neoplasm |

*Note that normal ranges will vary slightly among laboratories. | |

10.2.2 Abscess

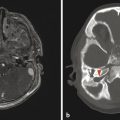

An abscess will typically have a peripheral contiguous rim of enhancement and centrally will demonstrate reduced water diffusion (Fig. 10.1). When the abscess is intra-axial, there will be surrounding edematous changes. An abscess, also known as an empyema, can occur in the subdural or epidural space (Fig. 10.2), in which case it is usually secondary to conditions like sinonasal/mastoid disease or penetrating trauma, or is postoperative.

10.2.3 Encephalitis

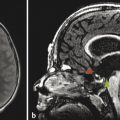

Encephalitis is a condition in which there is inflammation of the brain parenchyma itself, of either infectious or noninfectious origin. Because bacterial infection of the brain will usually lead to necrosis/abscess, encephalitis of infectious origin is typically related to a viral infection. A special consideration among viral encephalitides is herpes simplex virus (HSV) encephalitis, which most commonly presents as a febrile seizure. Such encephalitis is most often related to HSV-1 virus involved in an orofacial infection (such as a cold sore), in which there is reactivation of the virus in the trigeminal ganglion (also known as the gasserian ganglion) (refer to Fig. 9.6). Accordingly, the adjacent portion of the medial temporal lobe will be preferentially involved, as evidenced on imaging through a hyperintense T2/FLAIR signal, reduced water diffusion, and possibly postcontrast enhancement, with the eventual development of hemorrhagic necrosis. If this diagnosis is suspected, treatment with acyclovir should be started immediately (not waiting for confirmation of the diagnosis). Only upon a negative result of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for HSV on a CSF specimen should acyclovir therapy be discontinued.

In the neonatal period, HSV infection is more commonly related to the HSV-2 virus, may not involve the temporal lobes, and can have a scattered and random distribution (see Chapter 5) from hematogenous and/or CSF dissemination.

Other viral encephalitides tend to cause nonspecific edema predominantly in the gray matter, most often without abnormal enhancement, hemorrhagic changes, or diffusion abnormality.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree