12 Pancreas

The pancreas is a challenging organ to visualize with ultrasonography (US), and it is less commonly scrutinized than other intra-abdominal organs. It is a long, multilobular gland with important endocrine functions that include the secretion of insulin, glucagon, and somatostatin, as well as important exocrine functions that include the excretion of the enzymes amylase and lipase through the pancreatic ducts to the duodenum. The endocrine functions of the pancreatic islet cells regulate blood glucose levels, whereas the exocrine functions of the pancreas promote the digestion of carbohydrates and fat in the alimentary tract.

A thorough evaluation of the pancreas may reveal significant abnormalities, either isolated or in combination with lesions elsewhere. US is an excellent screening tool for the evaluation of the pediatric pancreas, although there are age groups and conditions in which other modalities may serve better. High-frequency transducers (7–12 MHz in neonates, 5–7 MHz in older children) and state-of-the-art machines equipped with Doppler imaging provide excellent visualization of the pediatric pancreas that compares favorably with that of other cross-sectional imaging techniques.

A complete US evaluation of the pancreas requires a meticulous technique with multiple views, in addition to knowledge of the important anatomical landmarks, normal changes in the appearance of the organ with age, and disorders that most frequently affect the pediatric pancreas. US changes looked for include alterations in size with focal or diffuse enlargement or atrophy, alterations in echogenicity, focal cystic or solid lesions inside or at the periphery of the organ, calcifications, adjacent lymphadenopathy, and alterations in the size of the pancreatic duct.

The pancreas should be scrutinized routinely during abdominal US, particularly in children with acute or chronic abdominal pain, increased amylase levels, known inherited diseases that can potentially affect the pancreas morphologically or functionally, hypoglycemic attacks, vomiting, a palpable mass, weight loss, increased levels of tumor markers, failure to thrive, jaundice, or anorexia.

The following paragraphs will describe conditions that affect the pediatric pancreas, with an emphasis on those that are appreciable with US.

12.1 Examination Technique

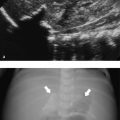

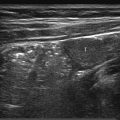

Examination of the pancreas with US usually occurs as part of an upper abdominal study, or of an upper and lower abdominal study. It is important to start the ultrasound examination with an evaluation of the pancreas before the child swallows air by talking or crying, and before air normally migrates toward the gastric antrum and transverse colon. The patient is scanned in a supine position. The hepatic left lobe is used as an appropriate window, combined with a subxiphoid transverse view. An oblique transverse view, following slight rotation counterclockwise parallel to the oblique orientation of the organ, evaluates as much of the body and tail as possible ( Fig. 12.1 ). More caudal views in the same direction, in an attempt to visualize the uncinate process of the pancreas, may be achieved by displacing the probe more caudally or by tilting the probe toward the patient’s feet ( Fig. 12.2 ). The distal body and tail of the pancreas may prove difficult to visualize anteriorly, and a rotated clockwise coronal view through the splenic hilum while the patient is turned toward the right ( Fig. 12.3 ), or through the left kidney while the patient is lying prone, may prove useful. Longitudinal views of the head and body through the hepatic left lobe complement the evaluation ( Fig. 12.4 ).

Gaseous distention of the stomach, small bowel, or colon may compromise an evaluation of the pancreas. Gentle or graded compression and patience are usually what works during sonography of the pancreas, together with tilting the probe toward the patient’s feet and slight rotation counterclockwise. Drinking liquids may not be as effective in children as in adults because children tend to swallow air as well, unless the examiner allows enough time for the bubbles to settle ( Fig. 12.5 ). One trick is to turn the patient on the right side for a few minutes and then back to a supine position, so that liquids may occupy the antrum and gas may move toward the fundus and colonic flexures for a few seconds, enough time to compress with the probe ( Fig. 12.6 ). The pancreas is better visualized after fasting; therefore, lastly, you may repeat the test following a 4-hour fast in children and a 3-hour fast in neonates.

Tips from the Pro

The pancreas should be the first organ evaluated during an upper abdominal study and the second organ (after the urinary bladder) during an upper and lower abdominal US examination.

Scanning the child in the prone, lateral decubitus, or erect position may improve visualization through the liver or left kidney and may move the transverse colon out of the way. Asking a cooperative child to exhale or push the tummy out for seconds may also help.

12.2 Normal Anatomy, Variants, and Pseudo-lesions

The pancreas is a long, unencapsulated, retroperitoneal organ that has an oblique orientation. It extends from the duodenal loop medially to the splenic hilum laterally and is located in the anterior pararenal space at the upper part of the abdomen, anterior to the splenic vein and portal venous confluence ( Fig. 12.1 , Fig. 12.2 , Fig. 12.5 , Fig. 12.7 ). The pancreas is comma-shaped on transverse scans with a uniform echotexture and a smooth outline.

The pancreas consists of the head (which ends caudally and medially as the uncinate process), the isthmus (or neck), and the body and tail, with no clear distinction between them. The pancreatic head envelops the teardrop-shaped portal vein just at the junction of the splenic vein and superior mesenteric vein and extends caudally to wrap under the superior mesenteric vein as the uncinate process, which resembles a hook on transverse scans ( Fig. 12.2 and Fig. 12.7 ). This area is particularly important to examine because it includes the distal common bile duct and pancreatic duct and may reveal important pathology ( Fig. 12.8 ). A vascular landmark at this point is the gastroduodenal artery, which arises from the common hepatic artery and courses downward by the anterior surface of the pancreatic head or isthmus, parallel to the common bile duct ( Fig. 12.7 and Fig. 12.8 ).

The neck or isthmus of the pancreas is the thinner part between the head and the body, anterior to the portal venous confluence ( Fig. 12.9 ). The pancreatic body lies posterior to the stomach or liver and anterior to the superior mesenteric artery. The superior mesenteric artery is anterior to the aorta and appears as the hole in a doughnut on transverse section because it is surrounded by a collar of echogenic fat ( Fig. 12.7 and Fig. 12.9 ). The bifurcation of the celiac artery into the hepatic and splenic arteries resembles a seagull in flight and is an important vascular landmark for the upper part of the pancreatic body ( Fig. 12.10 ). The tail of the pancreas is located anterior to the splenic vein and extends to the splenic hilum ( Fig. 12.1 and Fig. 12.3 ).

Nonvascular landmarks are the pancreatic duct and common bile duct. The common bile duct courses downward parallel to the gastroduodenal artery and posterior to the pancreatic head, and it may not be visible in children unless dilated ( Fig. 12.8 and Fig. 12.11 ). The pancreatic duct courses centrally within the pancreatic parenchyma from the tail to the head, and parts of it can be identified by US as an echogenic line ( Fig. 12.1 ) or as an echo-free lumen with echogenic walls ( Fig. 12.12 ). A ductal diameter of 1.5 mm or more should be considered abnormal in children up to 6 years age until proved otherwise. The hypoechoic muscular wall of the stomach should not be mistaken for the pancreatic duct, especially when the body is imaged obliquely and the gastric contents are isoechoic to the pancreas and may be erroneously mistaken for the pancreatic body ( Fig. 12.13 ).

The size of the pancreas varies depending on age. Measurements are shown in Fig. 12.14 and normal values in Table 12.1 . As a rule of thumb, when the thickness of the body is more than 1.5 cm, the pancreas is enlarged. The pancreatic head appears relatively voluminous compared with the body in children, which is normal. Care should be taken not to include the duodenal loop in the measurements or in the appreciation of the pancreatic head ( Fig. 12.15 ).

Age | Head | Body | Tail | Duct of Wirsung |

Newborn infants | 1.0 (0.4) | 0.6 (0.2) | 1.0 (0.4) | |

1 month–1 year | 1.5 (0.5) | 0.8 (0.3) | 1.2 (0.4) | |

1–3 years | 1.7 (0.3) | 1.0 (0.2) | 1.8 (0.4) | 1.13 (0.15) |

3–5 years | 1.7 (0.3) | 1.0 (0.2) | 1.8 (0.4) | 1.35 (0.15) |

5–10 years | 1.6 (0.4) | 1.0 (0.3) | 1.8 (0.4) | 1.67 (0.17) |

10–12 years | 2.0 (0.5) | 1.1 (0.3) | 2.0 (0.4) | 1.78 (0.17) |

13–15 years | 2.0 (0.5) | 1.1 (0.3) | 2.0 (0.4) | 1.92 (0.18) |

16–19 years | 2.0 (0.5) | 1.1 (0.3) | 2.0 (0.4) | 2.05 (0.15) |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation. Source: Reprinted with permission of the Radiological Society of North America from Siegel MJ, Martin KW, Worthington JL. Normal and abnormal pancreas in children: US studies. Radiology 1987;165(1):15–18. Note: In total, 273 patients (sex distribution not reported) were included in this retrospective ultrasound study. The maximum anteroposterior diameters of the head, body, and tail of the pancreas ( Fig. 12.14 ) were measured on transverse and oblique images. | ||||

The echogenicity of the pancreas varies; in general, it is equal to or slightly greater (but not much) than that of the normal liver, and its echotexture is smooth or minimally coarse ( Fig. 12.16 ). In about 10% of infants and children, it may be less echogenic than the liver. Care should be taken to evaluate the liver echogenicity as well, and not to mistake an isoechoic pancreas for a hypoechoic one in cases of hepatic steatosis ( Fig. 12.17 ) or for a hyperechoic one in cases of a hypoechoic liver due to hepatitis, in which the liver is also characterized by a starry sky appearance of the hepatic parenchyma.

An important feature is the different echogenicity of the posterior pancreatic head and uncinate process. This area originates embryologically from the ventral anlage and exhibits a hypoechoic appearance because of its relatively low fat content. It has a geographic border like an area of focal fatty sparing and no mass effect ( Fig. 12.18 ). A cause of pseudo-lesions is the acoustic shadowing produced by the gastric contents ( Fig. 12.19 ) or by the fibrofatty ligamentum teres ( Fig. 12.20 ). Scanning with slight obliquity should help to distinguish a true focal lesion from a pseudo-lesion.

Tips from the Pro

Knowledge of the vascular and nonvascular landmarks and multiple views with and without obliquity ensure visualization of all the pancreatic parts and avoid the misinterpretation of pseudo-lesions as true lesions. Routine measurements of the pancreas and pancreatic duct, and appreciation of its echogenicity compared with that of the liver, may increase the sensitivity of US in the detection of focal and diffuse pancreatic abnormalities.

12.3 Pathology

12.3.1 Developmental Anomalies

A knowledge of basic embryology is helpful in understanding the morphology and clinical importance of the most common developmental pancreatic abnormalities ( Fig. 12.21 ). The ventral anlage forms the uncinate process and part of the pancreatic head, while the dorsal anlage forms the remaining, larger part of the organ.

Pancreas divisum is the most common congenital anomaly of the pancreatic ductal system and is encountered in 4 to 10% of the population. Pancreas divisum results from failure of fusion between the ventral and dorsal pancreatic ducts ( Fig. 12.21 c). The ventral duct (duct of Wirsung) drains only the ventral pancreatic anlage, whereas most of the gland empties into the minor papilla through the dorsal duct (duct of Santorini). Pancreas divisum may be asymptomatic or present with chronic abdominal pain and recurrent pancreatitis in children ages 5 to 15 years because of functional stenosis at the minor papilla. US usually fails to diagnose this condition. Endoscopic retrograde pancreatography or magnetic resonance (MR) pancreatography demonstrates noncommunicating dorsal and ventral ducts, independent drainage sites, and a dominant dorsal pancreatic duct. The ventral duct is typically short and narrow.

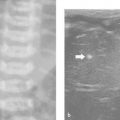

Annular pancreas is a rare congenital anomaly (1 in 2,000 persons) in which incomplete rotation of the ventral anlage causes a segment of the pancreas to encircle the second part of the duodenum ( Fig. 12.21 d). It occurs either in isolation or together with other congenital abnormalities, including tracheoesophageal fistula, duodenal stenosis or atresia in infants, Down syndrome, and congenital heart defects. Annular pancreas presents with proximal obstruction causing a “double-bubble” sign on radiographs in neonates, and with bile duct obstruction, associated pancreatitis, and “peptic ulcer”-like disease in older children. Annular pancreas can be diagnosed by US as pancreatic tissue encircling the duodenum, with proximal duodenal dilatation ( Fig. 12.22 ). Computed tomography (CT) and MR imaging may confirm these findings. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) may demonstrate an annular duct encircling the descending duodenum.

Ectopic pancreas occurs in 0.6 to 13.7% of the population and may be found in the stomach, duodenum, jejunum, a Meckel diverticulum, or ileum, and rarely in other abdominal sites ( Fig. 12.23 ). The ectopic tissue measures around 0.5 to 2.0 cm in diameter and is usually located in the submucosa. Ectopic pancreas is asymptomatic, although complications due to mass effect (stenosis, intussusception), ulceration, bleeding, pancreatitis, cystic degeneration, or malignancy may develop.

Other congenital abnormalities include pancreatic agenesis, which is extremely rare and incompatible with life, and partial agenesis or hypoplasia or congenitally short pancreas, which can occur in isolation or be associated with heterotaxy/polysplenia syndromes. The pancreas in hypoplasia consists of a short, enlarged, or globular pancreatic head and agenesis of the pancreatic body and tail due to the absence of dorsal anlage development ( Fig. 12.24 ). Patients who have agenesis of the dorsal pancreas often present with nonspecific abdominal pain, which may or may not be caused by pancreatitis, and they are at increased risk for diabetes mellitus. Situs inversus is inversion of the intra-abdominal contents and anatomical landmarks, with an intact pancreas ( Fig. 12.25 ).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree