15 Skull and Scalp

15.1 Introduction

The brain is a critical organ for survival. Protection of the brain from physical injury is primarily provided by its osseous and soft tissue coverings, including the meninges, the skull, and the overlying soft tissues of the scalp. Developmental and acquired abnormalities of the skull and scalp can occur throughout childhood. Many of these abnormalities are not commonly encountered in adults, and many radiologists and clinicians may not be familiar with them.

15.2 Normal Skull

The skull and skull base arise from multiple bones, each of which has several parts. These bones are divided between the neurocranium, which consists of the:

Ethmoid bone (cribriform plate)

Frontal bone

Occipital bone

Parietal bone

Sphenoid bone

Temporal bone (petrous and squamous parts)

and the viscerocranium, which consists of the:

Ethmoid bone

Hyoid bone

Inferior nasal concha

Lacrimal bone

Sphenoid bone (pterygoid process)

Temporal bone

Vomer

Mandible

Maxilla

Nasal bone

Palatine bone

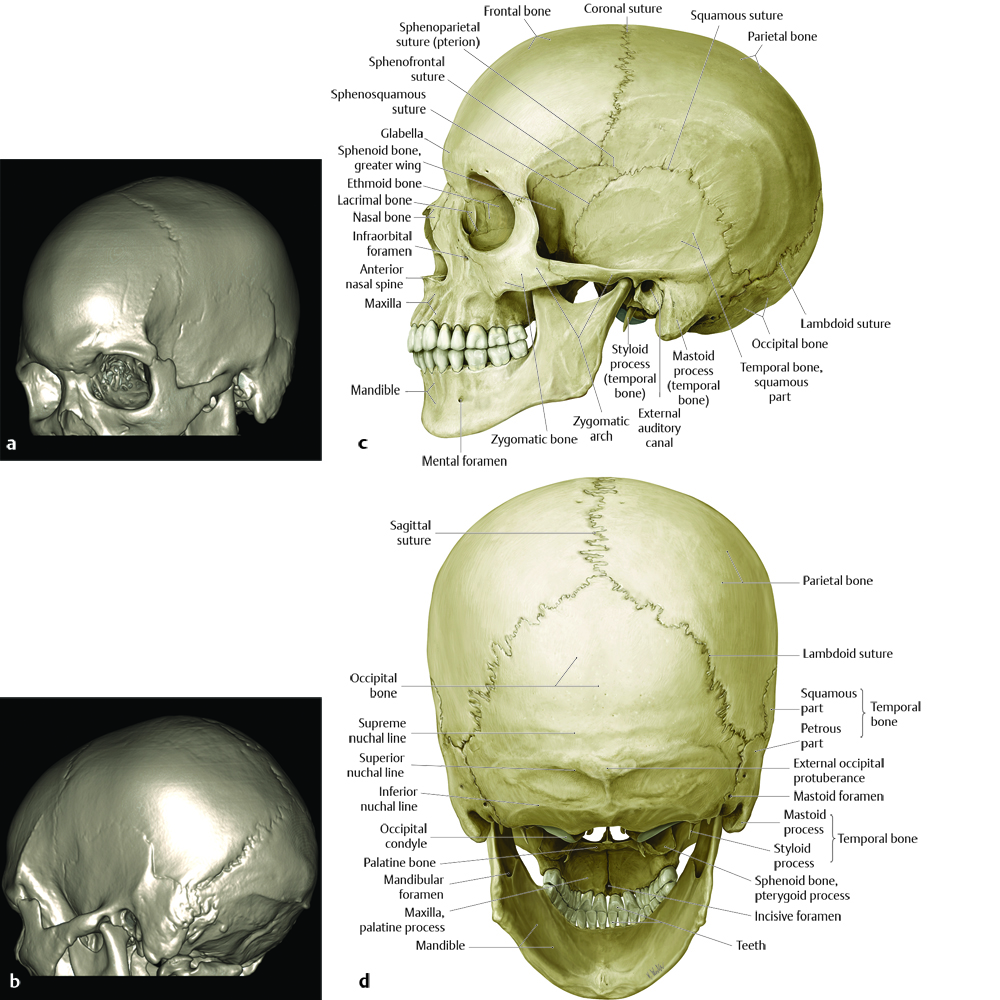

Note that some of the bones named above are divided between the neurocranium and viscerocranium (e.g., the ethmoid bone is mainly in the viscerocranium, the sphenoid bone is mostly in the neurocranium, and the temporal bone is equally present in the neurocranium and viscerocranium). The embryology and development of the skull are important for the correct identification of pathologic conditions, and also for avoiding the diagnosis of a normal developmental pattern as pathologic. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5

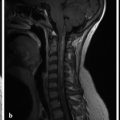

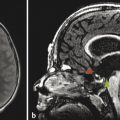

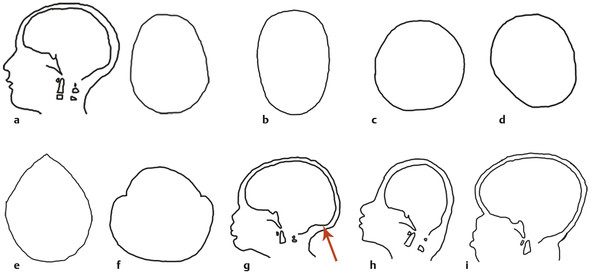

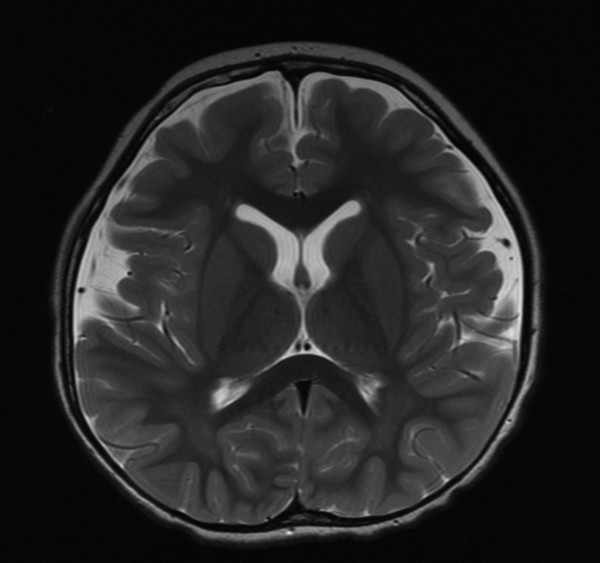

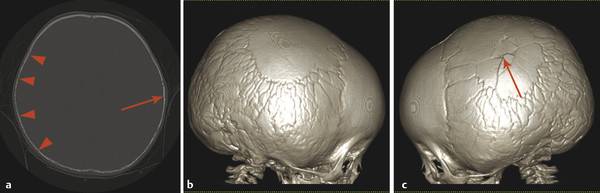

Understanding the anatomy of the developing skull may be easier when starting from knowledge of the mature skull (Fig. 15.1). Early in life, the sutures between the bones of the skull are unfused (Fig. 15.2), and typically mature in a symmetric pattern with a general order but some degree of variability. Three-dimensional (3D) computed tomographic reconstructions can greatly aid in understanding the anatomy of the skull, but familiarity with its anatomy in two-dimensional (2D) computed tomographic images (as well as on radiography) aids in detecting abnormalities.

Because the skull originates without a prominent diploic space, it appears on computed tomography (CT) as a single cortical layer at birth (Fig. 6.9). As the skull matures, the diploic space matures and a separate and distinct cortex develops for the inner cortex and another for the outer table, with trabeculae and marrow-containing spaces developing throughout the diploic space. The newborn skull is more susceptible to fracture than is the skull at later ages, partly because it is thin but also because it consists of a single layer of bone. The formation of two separate layers of cortical bone separated by an intervening trabeculated diploic space is more important than the increased thickness of the skull in providing improved stability as the skull grows. The support provided by the trabeculated diploic space is similar to the support provided by the central core in a sheet of corrugated cardboard, which is stronger than an equally thick layer of paper. Because of its susceptibility to fractures, close attention must be given to the newborn skull even in cases of seemingly minor trauma, and any fractures that do occur can be very difficult to detect without an understanding of the normal pediatric cranial anatomy.

Within the first 3 to 6 months of life, the metopic suture between the two frontal bones closes, and eventually, within the first 2 years, the anterior fontanelle disappears. The sagittal suture closes at a variable time, typically after 2 years of age. The remaining sutures have a somewhat variable pattern, but if the head is of normal circumference and shape, the maturation pattern of the sutures is likely to be normal.

15.3 Craniosynostosis

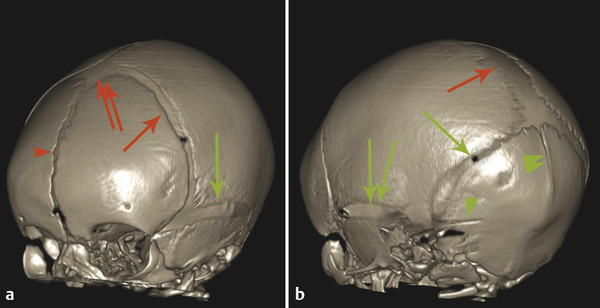

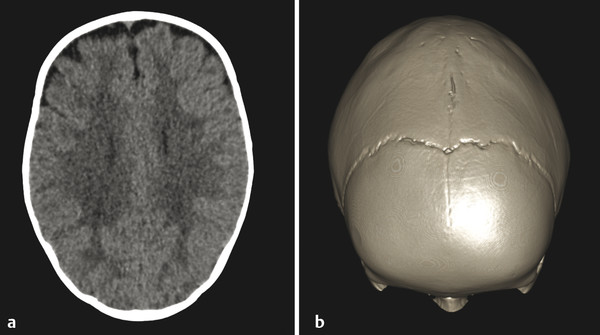

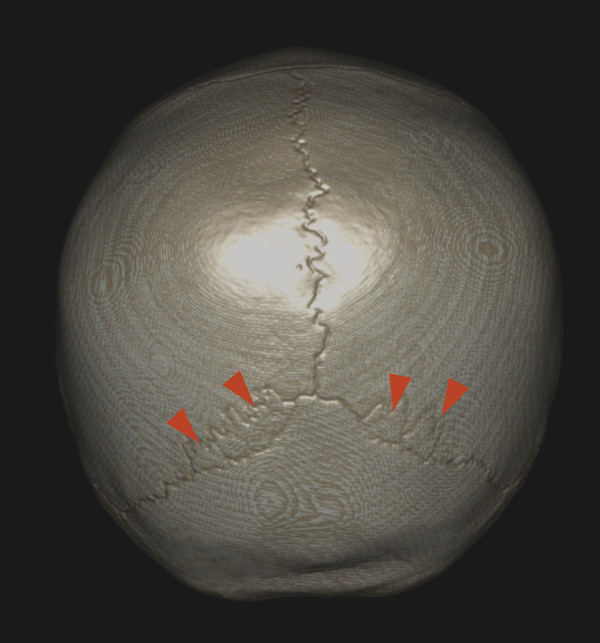

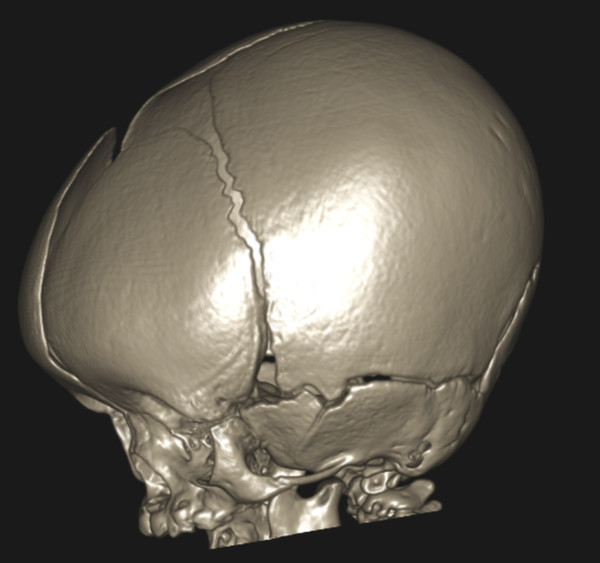

Early or abnormal closure of any cranial suture is referred to as craniosynostosis and can result in an abnormality of head shape (Fig. 15.3). 6 ,? 7 The most common craniosynostosis is premature closure of the sagittal suture (sagittal craniosynostosis), which impairs widening of the skull and results in a compensatorily increased anteroposterior (AP) dimension of the skull. This calvarial configuration is known as scaphocephaly (also known as dolichocephaly) (Fig. 15.4). If a case of scaphocephaly is symptomatic, surgery can be done to provide the cranial vault with the ability to expand. Expansion can both improve cosmesis and prevent elevated intracranial pressures. Isolated sagittal craniosynostosis is typically considered a sporadic finding; craniosynostosis of any other suture, alone or in conjunction with sagittal craniosynostosis, warrants a genetic evaluation.

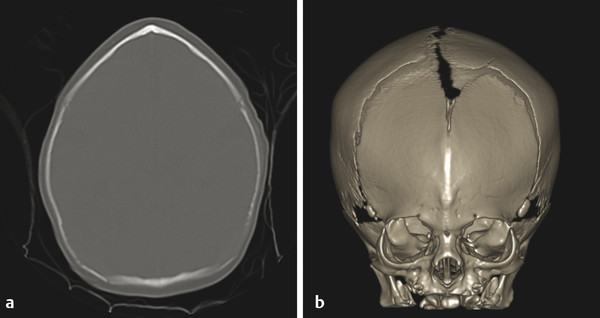

Premature closure of the metopic suture gives the frontal bone a keel-like appearance known as trigonocephaly (Fig. 15.5). 8 By itself, and in the absence of associated clinical signs of dysmorphism, the appearance of mild trigonocephaly on imaging can be a normal variant. Craniosynostosis of the coronal or lambdoid sutures can be unilateral or bilateral. Unilateral lambdoid craniosynostosis can result in asymmetric parieto-occipital flattening. Plagiocephaly, or flattening of one side of the head, can be due to pressure on that side, typically related to an affected child’s always sleeping on that side, and the differentiation of positional plagiocephaly from an abnormality in skull shape caused by craniosynostosis is a common indication for skull radiography or CT in early childhood. In positional plagiocephaly, which is far more common than unilateral lambdoid craniosynostosis, there will be a normal suture-maturation pattern (Fig. 15.6). Bilateral craniosynostosis of the coronal sutures is often associated with craniofacial syndromes like Apert syndrome and Crouzon syndrome, both of which are related to mutations in the FGFR2 gene. The bilateral craniosynostosis in both syndromes prevents skull growth in the AP dimension, resulting in a skull of brachycephalic shape (Fig. 15.7). Craniofacial syndromes and the FGFR gene are discussed in greater detail in Chapter 18.

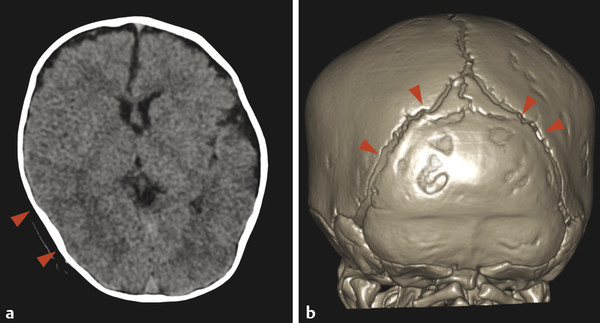

The developing skull can normally have intrasutural ossicles (also known as wormian bones), most commonly in the lambdoid suture (Fig. 15.8), and their presence has been detected with increased frequency through high-resolution CT scanning. An excess of intrasutural ossicles raises the possibility of a metabolic bone disorder, such as osteogenesis imperfecta (Fig. 15.9). 9 Other abnormalities of the pediatric skull related to systemic and/or metabolic bone disorders include persistence of the metopic suture in patients with supernumerary teeth and absence of the clavicle in cleidocranial dysostosis.

Prominence of the frontal bone (“frontal bossing”) and stenosis of the foramen magnum are features of skeletal dysplasias, and particularly of achondroplasia (Fig. 15.10), which is also marked by midface hypoplasia and jugular foraminal stenosis. The jugular foraminal stenosis in achondroplasia can lead to intracranial venous hypertension and a communicating hydrocephalus.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree