SP2 Atlantoaxial Subluxation

SP3 Bony Outgrowths of the Spine

SP4 Calcification of the Intervertebral Disc

SP5 Narrow Intervertebral Disc Height

SP6 Osteolytic Lesions of the Spine

SP7 Paraspinal Mass

SP8 Radiodense “Ivory” Vertebrae

SP9 Radiodense Vertebral Stripes

SP10 Sacroiliac Joint Disease

SP11 Scoliosis

SP12 Diminished Vertebral Height (Collapsed Vertebra)

SP13 Vertebral End-plate Alterations

Altered vertebral shape typically results from congenital conditions. Although a vertebra’s appearance may be altered in a myriad of ways, the following table includes some of the more commonly encountered alterations. Vertebral collapse and vertebral expansion are larger topics and therefore are discussed separately in this chapter.

SP1a. Beaked or Hooked Vertebrae

| DISEASE | COMMENTS |

|---|---|

| More common | |

| Achondroplasia [p. 421] | Congenital defect of endochondral bone formation, producing characteristic rounded lumbar “bulletnosed” vertebrae, lumbar kyphosis, posterior scalloping of the vertebrae, increased intervertebral disc height, flattened vertebral bodies, and narrowed spinal canal; the pelvis may appear hypoplastic; milder forms of the disease may occur. |

| Mucopolysaccharidoses [p. 444] | A group of lysosomal storage diseases marked by a common disorder in mucopolysaccharide metabolism, evidenced by various mucopolysaccharides excreted in the urine; these substances collect in connective tissue, resulting in bone, cartilage, and connective tissue defects; characteristics are platyspondyly with dwarfism, kyphosis, and alterations in the appearance of the vertebrae; mucopolysaccharidosis I (Hurler’s syndrome) is associated with oval, posteriorly scalloped, anterior inferiorly beaked vertebrae; mucopolysaccharidosis IV (Morquio’s syndrome) is associated with flattened, anterior centrally beaked vertebrae. |

| Normal variant | Slightly beaked vertebrae, most often occurring in the thoracic spine; the vertebral defect usually appears more wedged than beaked; the vertebral body may appear anteriorly beaked before ossification of the ring epiphyses; these steplike defects contain the cartilage growth centers of the vertebral endplate; as ossification proceeds, a focus of bone fills the radiolucent defect (6 to 12 years of age), fusing to the vertebral body at 20 to 25 years of age. |

| Less common | |

| Diastrophic dysplasia [p. 429] | Autosomal, recessive, rhizomelic dwarfism secondary to a cartilage disorder; it is characterized by multiple skeletal disorders, including progressive kyphoscoliosis, anteriorly deformed vertebrae, hypoplastic first metacarpal, clubfoot, and deformed flattened epiphyses. |

| Neurofibromatosis (von Recklinghausen’s disease) [p. 942] | Congenital disturbance of mesodermal and neuroectodermal tissue development, appearing clinically with cutaneous markings, bone deformity, and neurofibromas; spinal changes include posterior vertebral scalloping, enlarged intervertebral foramina, kyphoscoliosis, and anteriorly beaked or wedged vertebrae. |

| Cretinism [p. 915] | Congenital hypothyroidism with delayed appearance of ossification centers, skeletal underdevelopment, wormian bones, and poorly developed sinuses; sail-like or tonguelike vertebrae and kyphosis at the thoracolumbar junction are common; changes may regress in adulthood. |

SP1b. Biconcave Vertebrae

| DISEASE | COMMENTS |

|---|---|

| More common | |

| Metastatic bone disease [p. 889] | Metastatic bone deposition and subsequent tumor growth may weaken the vertebrae promoting endplate impaction, producing a biconcave deformity; metastasis typically occurs in patients over the age of 40 years and is more common in those with a personal history of primary malignancy. |

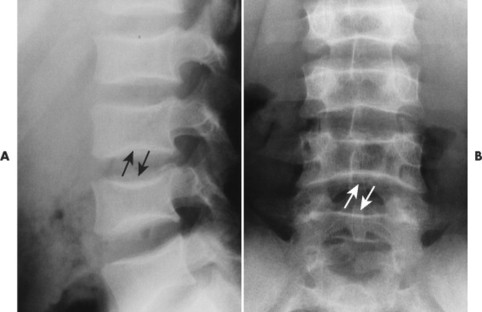

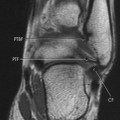

| Notochordal persistence(FIG. 17-1) | Nonfocal, congenital, smooth, inward deformity of all or part of the superior, inferior, or both vertebral endplates; this type of deformity is less focal and involves more of the endplate than Schmorl’s nodes. |

| Osteopenia (metabolic disorders) | Deformity from decreased bone mass secondary to rickets, osteomalacia, steroid therapy, hyperparathyroidism, malnutrition, senile osteoporosis, immobilization, or postmenopausal bone alterations. |

| Schmorl’s nodes [p. 456] | Prolapse of the nucleus pulposus into the vertebrae, producing abrupt, inward deformities of a focal area of the endplate; both endplates and multiple vertebrae may be involved. |

| Less common | |

| Gaucher’s disease [p. 933] | Genetic deficiency of glucocerebroside, with clinical findings of hepatosplenomegaly, osteopenia, osteonecrosis, focal osteolytic bone changes; biconcave vertebrae is a less common feature of the disease. |

| Homocystinuria(FIG. 17-2) [p. 438] | Genetic disorder causing defect in collagen metabolism. Its presentation is similar to Marfan’s disease; vertebrae appear osteopenic and biconcave or flattened. |

| Renal osteodystrophy [p. 910] | Secondary to renal glomerular disease; vertebral changes present with osteosclerosis (“rugger jersey”) and, less commonly, a biconcave appearance. |

| Sickle-cell anemia(FIG. 17-3) [p. 771] | Genetic abnormality in which red blood cells assume a sickled configuration in low oxygen tension; the sickled cells may occlude small vessels with resulting ischemia; skeletal changes include osteopenia, coarse trabeculae, biconcave (more precisely, steplike or H-shaped) vertebrae, and dactylitis. |

|

| FIG. 17-1 Biconcave appearance of, A, the cervical and, B, lumbar vertebrae in different patients’ notochordal persistency (or nuclear impression). |

SP1c. Blocked Vertebrae

| DISEASE | COMMENTS |

|---|---|

| Congenital | |

| Isolated anomalies(FIG. 17-4) | Congenital failure of segmentation; presentation varies from slight hypoplasia of intervertebral disc space to complete fusion of adjacent vertebral bodies and neural arches; interbody fusion and neural arch fusion are most common in the lumbar spine but frequently occur in the thoracic and cervical regions as well; the sagittal diameter of the vertebrae is decreased with an inward concavity of the anterior body margins at the site of segmentation failure; fusion of posterior elements and underdevelopment of the intervertebral disc space is common and used to differentiate congenital from acquired etiology. |

| Klippel-Feil syndrome(FIGS. 17-5and17-6) [p. 439] | Congenital failure of segmentation occurring at multiple levels; associated radiographic findings may include Sprengel’s deformity (elevation and medial rotation of the scapula), syndactyly, platybasia, and renal anomalies; patients usually demonstrate a clinical triad of a short neck, restricted cervical motion, and low posterior hairline. |

| AcquiredAnkylosing spondylitis [p. 739] | Acquired interbody fusion, seronegative spondyloarthropathy characterized by involvement in the sacroiliac joints and spine; the vertebrae appear square with ossification of the annulus fibrosus; disc height maintained; the disease has a strong male predominance and always involves the sacroiliac joints. |

| Infections | Acquired interbody fusion secondary to pyogenic (e.g., Staphylococcus) or tuberculosis infections; disc height usually is decreased or absent. |

| Rheumatoid arthritis(FIGS. 17-7and17-8) [p. 472] | Chronic inflammatory arthritide that may demonstrate acquired interbody fusion; occurs more commonly with juvenile than adult rheumatoid presentations; the spinous processes do not fuse, but the remaining vertebral arches may fuse, particularly in the juvenile form. |

| Surgical fusion | Acquired interbody fusion resulting from surgery; multiple levels may be involved; posterior joints typically are spared, intervertebral disc spaces are not visible; vertebral bodies may have a thick, square appearance, resulting from surgically placed paraspinal layers of bone as part of the fusion surgery. |

| Trauma | Acquired interbody fusion from bone remodeling after severe trauma. |

|

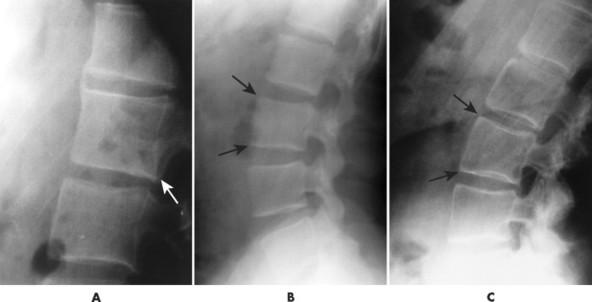

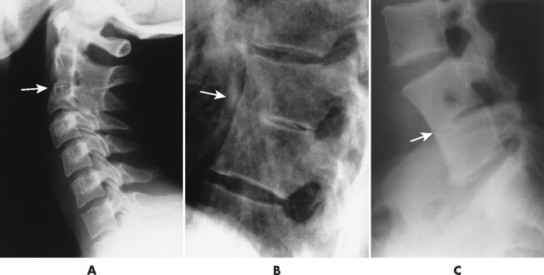

| FIG. 17-4 A, Cervical; B, thoracic; and C, lumbar congenital blocked vertebrae. All three patients exhibit hypoplasia of the intervertebral disc (arrows). |

|

| FIG. 17-6 Multiple congenital blocked segments of Klippel-Feil syndrome. Fusion is noted across the disc spaces and the vertebral arches. |

|

| FIG. 17-7 Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis demonstrating fusion across the posterior joints of C2-4 (arrow) and underdevelopment of the vertebral bodies and disc spaces (arrowheads). |

SP1d. Wide Enlarged Vertebrae

| DISEASE | COMMENTS |

|---|---|

| Acromegaly [p. 907] | Pituitary eosinophilic adenoma that produces excess somatotropin, leading to increased levels of growth hormone; the disorder is marked by progressive enlargement of the hands, feet, head, jaw, and abdominal organs; vertebrae are enlarged with posterior body scalloping; patients may have diabetes mellitus. |

| Expansile bone lesions (FIG. 17-9FIG. 17-10 and FIG. 17-11) | Examples of expansile lesions known to develop in the vertebrae: giant cell tumor, hemangioma, aneurysmal bone cyst, osteoblastoma, Paget’s disease, hydatid cyst, eosinophilic granuloma, fibrous dysplasia, chordoma, metastasis, osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, and angiosarcoma. |

| Paget’s disease(FIG. 17-12) [p. 946] | A generalized skeletal disease in which bone formation and resorption are both increased, leading to abnormally thick and soft bones with disorganized “mosaic” trabeculae; skull, pelvis, and vertebrae are common sites of involvement; vertebrae appear enlarged with thick cortices (“picture-framed” vertebrae). |

SP1e. Tall Enlarged Vertebrae

| DISEASE | COMMENTS |

|---|---|

| Blocked vertebrae [p. 439] | Associated with congenital or acquired etiologies, may appear as a single “tall” vertebra; a congenital etiology is indicated when the posterior arches are fused. |

| Gibbus formation | A gibbus formation, often developed from tuberculosis discitis in a child, may be associated with altered compressive forces on the vertebra, causing the lower segment of the gibbus to appear with increased vertical height along its posterior margin. |

| Marfan’s syndrome (arachnodactyly) [p. 441] | Congenital disturbance of collagen formation primarily expressed as defects of the skeleton and heart valves; skeletal changes include “tall” vertebrae, posterior vertebral scalloping, wide spinal canal, scoliosis, and a long, slender appearance of the metatarsals, metacarpals, phalanges, and long narrow bones (dolichostenomelia). |

| DISEASE | COMMENTS |

|---|---|

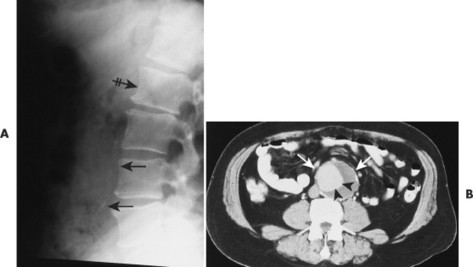

| Aortic aneurysms(FIGS. 17-13and17-14) [p. 1155] | Because of proximity, may cause erosions along the anterior left side of the vertebrae, which are sometimes termed Oppenheimer’s erosions; although not always present, the majority of cases also demonstrate calcification of the dilated vessel walls; the intervertebral disc is not involved. |

| Lymphadenopathy | Enlarged lymph nodes resulting from lymphoma, inflammatory lymphadenopathy, or metastatic lymphadenopathy may cause pressure erosions on the anterior surfaces of the vertebrae, primarily the lumbar vertebrae. |

| Normal variant | Mild in concavity; multiple levels are common; variants are most often seen in the lower thoracic and upper lumbar spine. |

| Tuberculosis [p. 779] | Common to find infectious erosions of the vertebral margins with paraspinal masses and involvement of the intervertebral disc. |

| DISEASE | COMMENTS |

|---|---|

| Achondroplasia [p. 421] | Congenital defect of endochondral bone formation resulting in the following spinal changes: posterior scalloping of the vertebrae, increased intervertebral disc height, flattened vertebral bodies, narrow spinal canal, lumbar kyphosis, “bullet-shaped” lumbar vertebrae; the pelvis may appear hypoplastic; milder forms of the disease may occur. |

| Acromegaly [p. 907] | Excess levels of growth hormone resulting from a pituitary eosinophilic adenoma overproducing somatotropin; the disorder is marked by progressive enlargement of the hands, feet, head, jaw, and abdominal organs; vertebrae are enlarged with posterior scalloping; patients may have diabetes mellitus. |

| Congenital syndromes(FIGS. 17-15and17-16) | Arachnodactyly (see previous Enlarged Vertebrae discussion), mucopolysaccharidosis syndromes (e.g., Hurler’s, Hunter’s, Morquio’s), Marfan’s syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, and others. |

| Increased intraspinal pressure | Increased intraspinal pressure from an ependymoma or communicating hydrocephalus may cause adjacent bone erosions. |

| Neurofibromatosis (von Recklinghausen’s disease) [p. 942] | Congenital disturbance of mesodermal and neuroectodermal tissues, appearing clinically with cutaneous markings, bone deformity, and neurofibromas; selected skeletal changes include kyphoscoliosis, enlarged intervertebral foramina, posterior vertebral body scalloping from dural ectasia or neurofibroma, and bowing deformity of the lower extremities. |

| Tumors | Bone erosion from adjacent spinal canal tumors (e.g., meningioma, ependymoma, lipoma, neurofibroma). |

SP1h. Square Vertebrae

| DISEASE | COMMENTS |

|---|---|

| Inflammatory arthropathies(FIG. 17-17) | Square vertebrae is one of the earliest findings of ankylosing spondylitis; square vertebrae also may be a feature of psoriatic arthritis, Reiter’s syndrome, and rheumatoid arthritis (usually juvenile); the seronegative inflammatory arthropathies usually involve the sacroiliac joints. |

| Paget’s disease [p. 946] | A generalized skeletal disease in which bone formation and resorption are both increased, leading to abnormally thick, soft bones with disorganized “mosaic” trabeculae; skull, pelvis, and vertebrae are common sites of involvement; vertebrae usually appear enlarged and square with thick cortices (“picture-framed” vertebrae). |

SP1i. Wedged Vertebrae

| DISEASE | COMMENTS |

|---|---|

| Congenital syndromes | Possible causes of wedged congenital vertebrae and other characteristic alterations; syndromes include achondroplasia, hypothyroidism, and mucopolysaccharidoses; usually multiple levels are involved. |

| Hemivertebrae(FIG. 17-18) | Focal vertebral hypoplasia, resulting in a lateral, anterior, or posterior wedged hemivertebra at one or multiple levels; lateral hemivertebrae produce scoliosis; posterior hemivertebrae are commonly posteriorly displaced up to 3 mm and produce a kyphosis. |

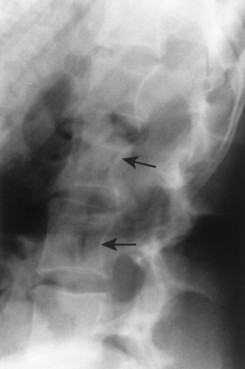

| Infections(FIG. 17-19) | Tuberculosis and pyogenic infections (e.g., Staphylococcus); clues to an infection include involvement of intervertebral disc space, paraspinal masses and calcifications, cortical demineralization, and angular kyphosis. |

| Normal variant Scheuermann’s disease [p. 456] | Slightly wedged vertebrae may occur as normal variants, usually in the thoracolumbar region. Posttraumatic defect of vertebral endplate maturation presenting during adolescence with three or more levels of wedged vertebrae, narrowed anterior disc space, multiple Schmorl’s nodes, and vertebral endplate irregularity; the disease usually develops in the middle and lower thoracic spine. |

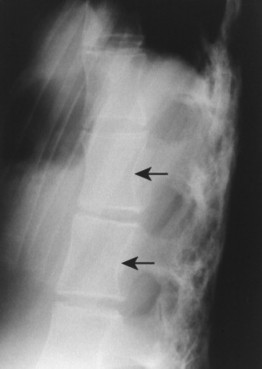

| Trauma(FIGS. 17-20and17-21) | Compression fracture leading to wedged configuration; endplate defects, cortical offset of anterior body margin (“step defect”), horizontal zone of bone impaction within vertebrae (zone of condensation), and history of trauma are clues to traumatic etiology. |

|

| FIG. 17-19 Infection leading to the trapezoidal shape of a middle thoracic vertebra with destructive endplate changes and narrowing of the intervertebral disc space (arrow). |

|

| FIG. 17-20 Compression fracture in the upper lumbar spine (arrow) and multiple levels of costal cartilage calcification (arrowheads). |

The normal measurement of the atlantodental interval (ADI) is less than or equal to 5 mm in children and 3 mm in adults. A measurement beyond these limits suggests instability of the atlantoaxial articulation. Instability results from compromise of the transverse atlantal ligament or C2 odontoid process. Because the joint is most stressed during flexion, forward flexion radiographs provide a more specific measure of ADI enlargement than neutral lateral radiographs. If the anterior tubercle or odontoid process does not represent fixed, clearly defined points of mensuration, atlantoaxial instability can be assessed by choosing another point on the atlas and axis, such as the distance between the posterior surface of the odontoid and the anterior surface of the posterior tubercle of the atlas (this space is known as the posterior atlantodental interval or PADI).

| DISEASE | COMMENTS |

|---|---|

| Congenital conditions | Occipitalization of atlas, Down syndrome (20% of cases), Morquio’s syndrome, and spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia; these are associated with atlantoaxial subluxation secondary to absence or attenuation of the transverse atlantal ligament, occurring as an isolated anomaly or in association with other defects. |

| Inflammatory spondyloarthropathy(FIG. 17-22) | Condition that includes rheumatoid (adult and juvenile types) arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, Reiter’s syndrome, and systemic lupus erythematosus; these are associated with synovitis, ligament attenuation, and odontoid erosions, which may lead to instability of the atlantoaxial articulation; rheumatoid arthritis is the most common inflammatory arthropathy to involve the atlantodental joint. |

| Marfan’s syndrome [p. 441] | Genetic disorder of connective development that leads to ocular, cardiovascular, and musculoskeletal abnormalities; joint instability follows ligamentous laxity. |

| Odontoid anomalies [p. 309] | Aplasia, hypoplasia, or malunion of the odontoid process may lead to instability. |

| Regional infections | Include retropharyngeal abscesses, otitis media, mastoiditis, cervical adenitis, parotitis, and alveolar abscesses. |

| Trauma | Instability resulting from fracture or torn ligaments. |

Most bony outgrowths of the spine represent osteophytes, related to degenerative arthropathy of the intervertebral disc spaces or posterior joints. An appearance of multilevel, flowing, thick, mostly anterior paravertebral outgrowths is characteristic of diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH). Large, coarse, incompletely bridging paravertebral outgrowths are associated with Reiter’s syndrome and psoriatic arthropathy. In contrast delicate, thin, completely bridging outgrowths (marginal syndesmophytes) are characteristic of ankylosing spondylitis. As the terms are generally used, osteophytes denote a degenerative etiology and syndesmophytes an inflammatory etiology. Because the condition is classified as idiopathic, the bony outgrowths of DISH are neither osteophytes nor syndesmophytes; rather, exostasis or another generic term is used to describe the changes.

| DISEASE | COMMENTS |

|---|---|

| More common | |

| Ankylosing spondylitis(FIG. 17-23) [p. 492] | Seronegative spondyloarthropathy characterized by arthritis targeted to the sacroiliac joints and spine; bilateral, symmetric, thin intervertebral connections, known as syndesmophytes, are prominent features, representing ossification of the outermost lamellae of the annulus fibrosis; posterior joint fusion is common; collectively, multiple levels produce a “bamboo spine” appearance; in addition, the anterior body margins appear straight or square. |

| Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis(FIG. 17-24) [p. 583] | Idiopathic disease marked by thick, flowing anterior longitudinal ligament ossifications along the anterior and lateral body margins; diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) is most common in the thoracolumbar region. |

| Reiter’s syndrome and psoriatic arthropathy(FIGS. 17-25and17-26) [p. 510] Spondylosis deformans (degenerative disc disease)(FIG. 17-27) [p. 578] | Inflammatory arthropathies associated with paravertebral ossifications incompletely bridging the intervertebral disc spaces; usual to the thoracolumbar spine; the paravertebral ossifications are typically thick, but uncommonly may appear thin; the latter appearance is identical to those of ankylosing spondylitis. as curved (“claw”) or horizontal (“traction”) vertebral osteophytes, with or without other findings of degenerative disc disease (e.g., endplate osteosclerosis and irregularity, narrowed disc space, misalignment). Osteophytes form in response to increased tension at the Sharpey’s fibers, anchoring the outer annulus into the cortical bone of the adjacent endplate. Degenerative osteophytes are moderately thick (thicker than ankylosing spondylitis, thinner than DISH) and typically incompletely bridge the intervertebral disc space. |

| Less common | |

| Acromegaly [p. 907] | Excess levels of growth hormone resulting from a pituitary eosinophilic adenoma overproducing somatotropin; the disorder is marked by progressive enlargement of the hands, feet, head, jaw, and abdominal organs. Vertebrae are enlarged with posterior scalloping and new bone growth along the anterior body margins. |

| Fluorosis | Chronic fluoride intoxication associated with osteophytosis and vertebral hyperostosis with calcification of the paraspinal ligaments; vertebrae have increased radiodensity; fluorosis is most marked in the innominates and lumbar spine. |

| Hypoparathyroidism [p. 913] | Inadequate parathormone from undersecretion or surgical removal of the gland; skeletal changes include increased or decreased radiodensity, thickened calvarium, premature fusion of ossification centers, and ossification of the paraspinal ligaments. |

| Neuropathic spine [p. 584] | Primarily caused by diabetes mellitus, syringomyelia, and tabes dorsalis; the radiographic appearance is marked by loss of intervertebral disc height, increased bone radiodensity, misalignment, fragmentation, and prominent osteophytosis. |

| Ochronosis | Inherited disorder of excessive homogentisic acid production and subsequent accumulation within connective tissues; the spine is affected by multiple levels of intervertebral disc calcification and massive osteophytosis and ankylosis, especially in the elderly. |

| Trauma | May cause bony outgrowths from degenerative joint changes or dystrophic tissue calcifications. |

|

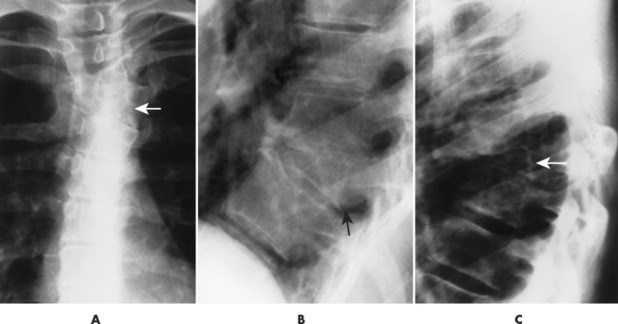

| FIG. 17-23 A through D, Thin, bridging syndesmophytes characteristic of ankylosing spondylitis in four patients (arrows). |

|

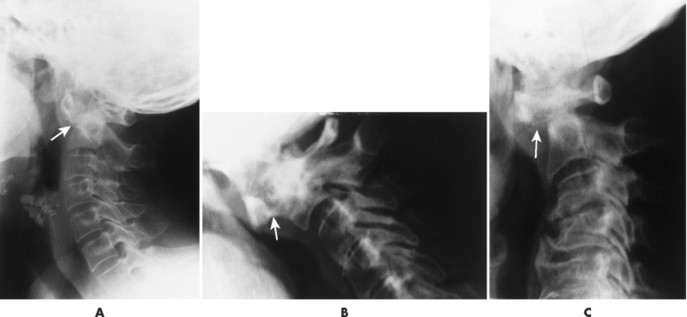

| FIG. 17-24 Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis affecting, A, the cervical and, B, lumbar spines of different patients. |

|

| FIG. 17-26 Psoriatic spondyloarthropathy with characteristic thick syndesmophytes incompletely bridging the disc space (arrow). |