20 Sinuses

20.1 Nasal Cavity and Paranasal Sinuses

The paranasal sinuses are aerated cavities within the facial bones that serve a variety of roles, including the humidification of inhaled air, contributing to immunologic defenses, and decreasing the weight of the skull. A variety of infectious, inflammatory, and neoplastic entities can occur within the paranasal sinuses throughout childhood and adolescence, largely mirroring pathologic conditions in adults. Additionally, there are a variety congenital abnormalities of the paranasal sinuses, and variants of these abnormalities, that require awareness.

20.2 Anatomy

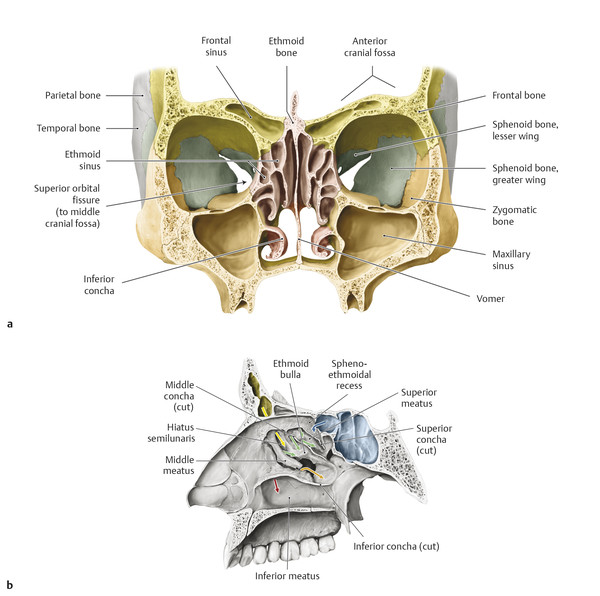

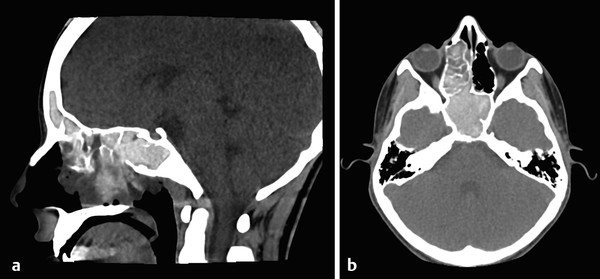

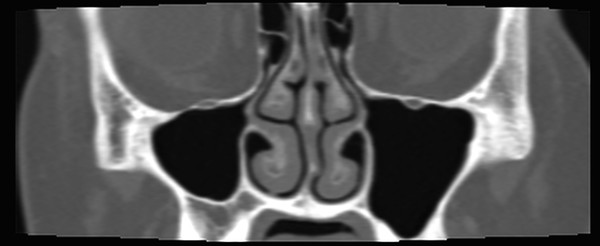

There are four pairs of paranasal sinuses, within different facial bones (Fig. 20.1). The largest are the maxillary sinuses, which are lateral to the nasal cavity, below the orbits and above the posterior maxillary alveolus. The maxillary sinuses communicate with the nasal cavity through the osteomeatal complex, and drain near the hiatus semilunaris. The ethmoid sinuses are a multiseptated series of air cells located above the nasal cavity and medial to the orbit. The ethmoid sinuses are separated from the orbit by the lamina papyracea. Superiorly, the ethmoid sinuses are separated from the anterior cranial fossa by the cribriform plate medially and the fovea ethmoidalis laterally. The frontal sinuses, in the frontal bones superior to the anterior aspect of the orbits, drain through a frontoethmoidal recess that extends toward the hiatus semilunaris. Posterior to the ethmoid bones are the sphenoid sinuses, which develop within the basisphenoid. The sphenoid sinuses drain into the posterior ethmoid sinuses through the sphenoethmoidal recess (s. Tab.).

Sinuses/Duct | Nasal passage | Pathway | |

Sphenoid sinus | Sphenoethmoidal recess | Direct | |

Ethmoid sinus | Posterior cells | Superior meatus | Direct |

Anterior and middle cells | Middle meatus | Ethmoid bulla | |

Frontal sinus | Middle meatus | Frontonasal duct into hiatus semilunaris | |

Maxillary sinus | Middle meatus | Hiatus semilunaris | |

Nasolacrimal duct | Inferior meatus | Direct | |

Used with permission from Gilroy A, MacPherson B, Ross L. Head & Neck: Nasal Cavity and Nose. In: Gilroy A, MacPherson B, Ross L, eds. Atlas of Anatomy. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Thieme;2012:552. | |||

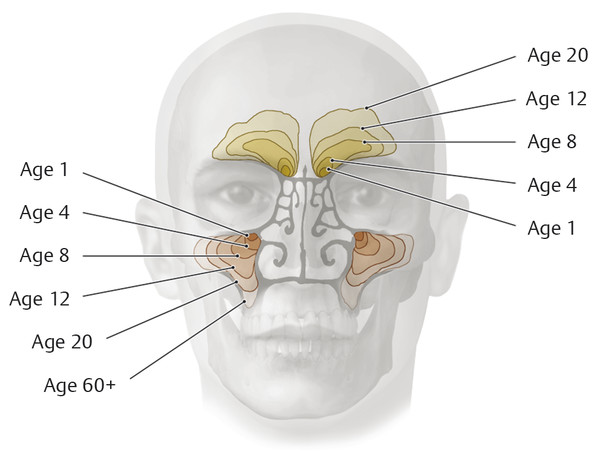

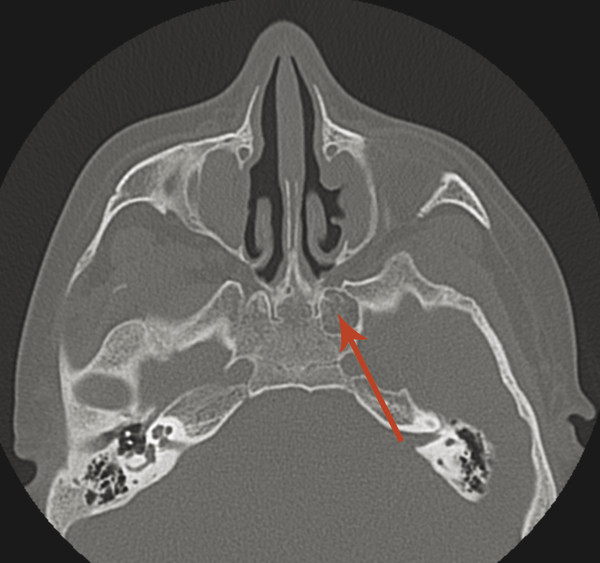

The sinuses develop over the course of childhood. The ethmoid sinuses are present at birth, as are the maxillary sinuses in their rudimentary form. The maxillary sinuses develop over the first decade of life, followed by the sphenoid sinuses and, variably, the frontal sinuses (Fig. 20.2). The sphenoid sinuses develop within the basisphenoid, and at times there is lateral pneumatization of pterygoid recesses extending into the pterygoid process of the sphenoid bone. In some children, the development of the sphenoid sinus is arrested, typically in an asymmetric manner (Fig. 20.3). It is important to be aware of this entity because it can be mistaken for a lesion of the skull base.

20.3 Sinonasal Infections

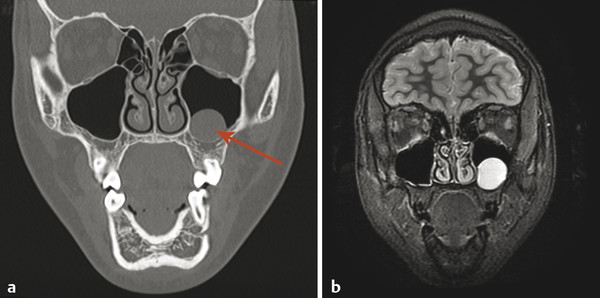

Sinonasal infections are common throughout childhood. Mucosal thickening along the margins of the paranasal sinuses does not necessarily represent an acute bacterial sinusitis. Focal globular thickening usually represents a mucous retention cyst (Fig. 20.4) rather than a polyp. Discrete polyps are typically not visible on cross-sectional imaging. The presence of fluid levels or bubbly secretions may be indicative of acute sinusitis, but fluid levels alone are nonspecific, and can be seen after swimming. The drainage pathways to a sinus can become obstructed, preventing the drainage of infectious debris and possibly exacerbating symptoms of sinusitis (Fig. 20.5). Acute sinusitis can result in bony erosion.

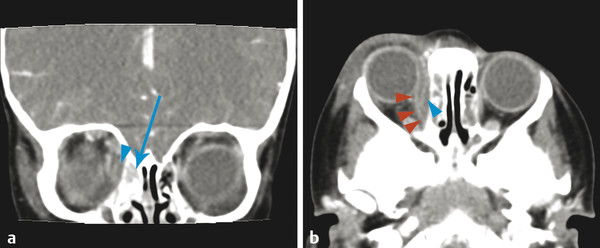

Three complications of acute sinusitis require awareness. The first is erosion through the lamina papyracea, which can result in orbital cellulitis (Fig. 20.6). The other two, Pott’s puffy tumor, and epidural/subdural empyema, originate from the frontal sinuses, and can extend through the anterior wall into the subcutaneous soft tissues of the forehead, resulting in the swelling known as Pott’s puffy tumor (Fig. 10.2) (which despite its name is a non-neoplastic condition). The extension of an infectious process in the frontal sinus through the posterior wall can result in its further intracranial extension and an epidural and/or subdural empyema (Fig. 10.2), which is a surgical emergency.

Chronic infection can result in thickening and sclerosis of the osseous margins of the paranasal sinuses (Fig. 20.7).

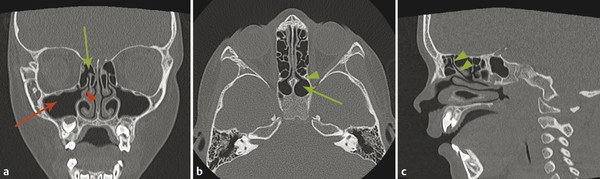

A subtype of chronic sinusitis is allergic fungal sinusitis (Fig. 20.8). The characteristic appearance of this on imaging is that of high-density matter within the paranasal sinuses. The high density represents noninvasive fungal hyphae, with the density possibly also related to the presence of metalloproteases. The chronic space-filling process in this sinusitis can result in expansion of the sinuses and even in hypertelorism (Fig. 20.8). When suggesting this diagnosis, it is important to specifically state that the diagnosis is allergic fungal sinusitis, which is a chronic process. This is in contradistinction to invasive fungal sinusitis, an acute aggressive process seen most commonly in immunocompromised patients and which represents a surgical emergency.

A partial obstruction of the osteomeatal complex of the maxillary sinuses can effectively create a one-way valve. If this allows air to move out of the sinus more easily than it can move into the sinus, it will result in a chronic vacuum effect within the sinus, causing the sinus to become smaller over the course of time. An asymmetrically smaller, or atelectatic, maxillary sinus is a sequela of this chronic sinus problem that may be clinically asymptomatic, yielding the name “silent sinus syndrome” (Fig. 20.9). This is important to recognize because the syndrome can eventually result in lowering of the floor of the orbit, creating visual symptoms, such as double vision.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree