Bronchial Asthma

Bronchiectasis

Bronchopulmonary Sequestration

Congenital Bronchogenic Cysts

Emphysema

Atelectasis

BACKGROUND

General.

Atelectasis is defined as incomplete air filling and underexpansion of pulmonary tissue. It should be distinguished from consolidation, which also represents incomplete air filling of the lung. However, in consolidation, the missing air is replaced by blood, edema, pus, or another space-occupying substance, whereas missing air of an atelectatic region is not replaced, resulting in segmental collapse. Atelectasis may involve the entire lung or appear localized to a lobe, segment, or subsegment of the lung. It is not a disease itself, but rather a radiographic sign suggesting the presence of another pathology. Based on the underlying mechanism, atelectasis is divided into five categories: obstructive, passive, compressive, adhesive, and cicatrization.

Obstructive atelectasis.

The first and most common type of atelectasis is termed obstructive or resorptive atelectasis. It is caused by intrinsic or extrinsic obstruction of an airway by such phenomena as neoplasm, infection, foreign body, and heavy secretions. 2,6 Over time, air distal to the airway obstruction is resorbed and not replaced, leading to an airless, radiolucent, collapsed portion of lung tissue (FIG. 22-1FIG. 22-2FIG. 22-3FIG. 22-4FIG. 22-5 and FIG. 22-6). Often the lung distal to bronchial obstruction exhibits increased radiopacity correlating to replacement of the alveolar air with inflammatory transudate, exudate, or other substance. Less commonly, a check-valve or obstruction develops, creating a hyperlucent, overinflated portion of lung tissue.

|

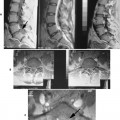

| FIG. 22-1 Pulmonary tissue may collapse secondary to a bronchial obstruction (obstructive), expanding intrapleural lesion (passive), expanding intrapulmonary lesion (compressive), and scarring contracture of the lung tissue (cicatrization). A fifth type, adhesive, is less common and presents in infants with hyaline membrane disease. |

|

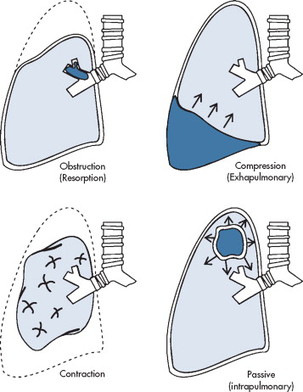

| FIG. 22-2 Collapse of the patient’s left lung with proximal shift of the patient’s left hemidiaphragm, heart, and trachea. (Courtesy John A.M. Taylor, Seneca Falls, NY.) |

|

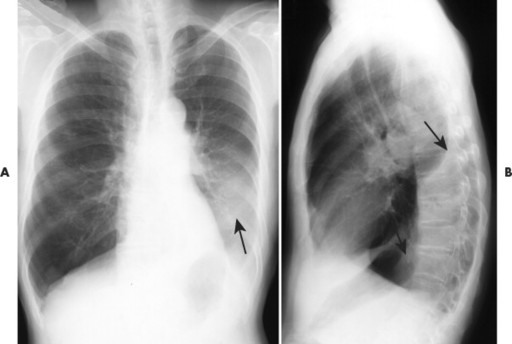

| FIG. 22-3 A 53-year-old male patient with a fracture of the left sixth rib (arrow). The elevated left hemidiaphragm suggests volume loss of the left lung. Also, blunting of the lateral costophrenic angle denotes pleural effusion (crossed arrow). (Courtesy John A.M. Taylor, Seneca Falls, NY.) |

|

| FIG. 22-4 A, Atelectasis of the left lower lobe presenting as a hazy radiodense shadow in the left lower margin of the lung field (arrow) and, B, posterior shift of the oblique fissure (arrows). (Courtesy John A.M. Taylor, Seneca Falls, NY.) |

|

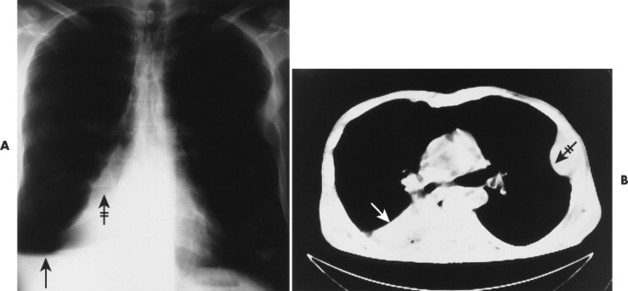

| FIG. 22-5 Obstructive atelectasis of the right middle and lower lobe. A, The plain film radiograph demonstrates an elevated right hemidiaphragm (arrow) and loss of the silhouette of the right heart border (crossed arrow). B, Computed tomography reveals an airless lung mass in the right costal angle (arrow) and left rib mass, representing costal metastasis (crossed arrow). |

|

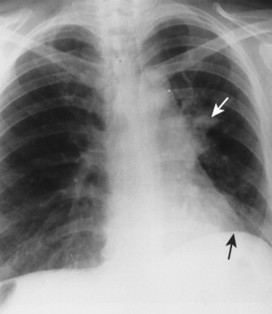

| FIG. 22-6 Tracheal carcinoma with left hilar mass (white arrow) and partial obstructive atelectasis of the left lung and elevation of the left hemidiaphragm (black arrow). (Courtesy Steven P. Brownstein, MD, Springfield, NJ.) |

A check-valve mechanism involves accumulation of air distal to an airway obstruction. Airways dilate during inhalation, permitting air to pass by a partial bronchial obstruction. Airways constrict tightly around an obstruction during exhalation, effectively limiting the expiration of air distal to the obstruction. With each breathing cycle, more air is “pumped” into the overinflated lung tissue distal to the obstruction. Check-valve obstructions in a small airway are of limited clinical significance; however, they may result in respiratory distress when present in a large airway.

Passive atelectasis.

Passive (relaxation) atelectasis is the second type of atelectasis and results from the presence of a space-occupying lesion external to the lung. Pleural fluid (blood, exudate, transudate, and chyle) or air may accumulate to such an extent that the adjacent lung is “pushed” aside, resulting in partial or complete pulmonary collapse. Diaphragmatic elevation or herniation of abdominal viscera also may compress the lung. The amount of collapse is proportional to the size of the space-taking lesion.

Compressive atelectasis.

Compressive atelectasis is a form of passive atelectasis in which the space-taking lesion is located within the involved lung. Large bullae, neoplasms, abscesses, and other large lesions may result in compressive atelectasis of adjacent lung tissue.

Adhesive atelectasis.

Adhesive atelectasis refers to the nonobstructive, noncompressive pulmonary collapse secondary to decreased surfactant production by the type II pneumonocytes. 31 Pneumonocyte damage results from genetic defects, general anesthesia, ischemia, or radiation damage. Adhesive atelectasis is seen in neonates afflicted with hyaline membrane disease.

Cicatrization atelectasis.

Finally, cicatrization atelectasis represents scarring and contracture of pulmonary tissue after infection, pneumoconioses, scleroderma, radiation, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, and so on. This condition may appear localized (tuberculosis in the lung apices) or generalized (interstitial pulmonary fibrosis).

IMAGING FINDINGS

The presence of atelectasis is suggested by direct and indirect radiographic signs (Box 22-1). Displacements of intralobar fissures are the most reliable findings. The radiographic appearance differs based on the degree of lung involvement, location, and type of atelectasis (Table 22-1). Combined lobar collapse may complicate the radiographic appearance. 16 Rounded atelectasis is a form of peripheral pulmonary collapse that must be differentiated from similarly appearing neoplastic masses. 20,32

BOX 22-1

Direct and Indirect Signs of Lobar Atelectasis

Direct signs

Displacement of interlobular fissures

Increased radiopacity*

*Some sources consider increased radiopacity an indirect sign of atelectasis.

Indirect signs

Elevation of the diaphragm

Mediastinal displacement

Hilar displacement

Overinflation of remaining normal lung

Approximation of pulmonary vessels

Approximation of ribs

| *Multiple lobes may be collapsed, yielding a combination of findings. | |

| Atelectasis | Imaging findings |

|---|---|

| Lung | Opacification of the entire hemithorax, compensatory shift of the mediastinum with overinflation and herniation of opposite lung toward collapsed lung side |

| Lobe* | |

| Right upper lobe | Radiodense lobe displaced superomedially, superiorly displaced diaphragm, oblique and horizontal fissures; can see the characteristic reversed “S-shape of Golden sign”10 when a central mass is found in combination with the displaced horizontal fissure |

| Right middle lobe | Best demonstrated on the lateral projection, where the minor and major fissure approximate one another, bordering a thin, oblique-to-horizontal density; loss of silhouette of the left heart border on the frontal projection; on frontal projection, lordotic projection best for visualizing a wedge-shaped density with base adjacent to heart border |

| Right lower lobe | Radiodense lobe displaced posteromedially with posterior displacement of oblique fissure noted on lateral projection |

| Left upper lobe | Radiodense lobe displaced anterolaterally with overinflation of lower lobe occasionally located between collapsed upper lobe and mediastinum, “Luftsichel” sign35 |

| Left lower lobe | Radiodense lobe displaced posteromedially, often obstructed by heart shadow; posterior displacement of the oblique fissure on the lateral projection |

| Segment | Increased radiodensity and volume loss that correspond to region collapsed and appear less marked than lobe involvement |

| Subsegment | Also known as platelike, discoid, or linear atelectasis; represents peripheral atelectasis of small areas of pulmonary tissue appearing as 2 to 10 cm horizontal linear density in the lower lung field |

| Round (folded lung) | Rare form of atelectasis associated with asbestosis-related pleural disease, in which the involved lung appears as a round mass (2 to 7 cm) in the lower lung |

CLINICAL COMMENTS

Whenever atelectasis is noted, it should prompt a vigorous search for a cause. Although several mechanisms of collapse have been identified, obstruction of the airway resulting from neoplasm is a common cause of lobar or segmental atelectasis that should direct patient management.

• Atelectasis is a sign of underlying disease process, defined as incomplete inflation of the lung.

• The five categories of atelectasis are obstructive, compressive, passive, adhesive, and cicatrization. Obstructive is the most common.

• The radiographic appearance depends on the location and extent of collapse; findings include loss of pulmonary volume, increased radiopacity, and distorted anatomic structures.

Bronchial Asthma

BACKGROUND

Bronchial asthma is characterized by widespread, episodic, reversible narrowing of the airways resulting from smooth muscle spasm, mucosal edema, or excess mucus in the lumen of the bronchi and bronchioles. A wide variety of inciting factors have been identified, including the following: exercise, infection, pharmaceuticals, and hypersensitivity to known allergens, such as pollen, animal fur, and fungi.

IMAGING FINDINGS

Early in the disease process no imaging findings are evident between acute episodes of the disease. However, radiographs taken at the time of an acute attack demonstrate increased radiolucency secondary to general lung overinflation and depression of the diaphragm. 21,23 Patients who suffer from chronic asthma attacks may demonstrate increased prominence of the central interstitial markings and, when projected on end, bronchial wall thickening greater than 1 mm. 13,18 The radiographic findings may be complicated by the presence of infection or mucous plugs resulting in atelectasis5 (Fig. 22-7) or consolidation. 3

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree