Aortic Aneurysms

Coarctation of the Aorta

Congenital Heart Disease

Congestive Heart Failure

Pleural Effusion

Pulmonary Edema

Pulmonary Thromboembolism

Acquired Valvular Heart Disease

BACKGROUND

IMAGING FINDINGS

Chest radiographs of patients with valvular heart disease typically demonstrate changes in the size of the cardiac shadow, alterations in the size and configuration of specific heart chambers, and alterations in pulmonary vascularity (Figs. 23-1 and 23-2). Valvular calcification also may be present, suggesting mitral and aortic stenosis of the involved value. Specific radiographic findings are listed in Table 23-1. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be helpful in providing anatomic and functional information about patients with valvular heart disease. 8,17

|

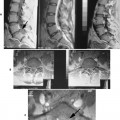

| FIG. 23-1 Raised pulmonary venous pressures in a patient with mitral stenosis. Note that the vessels in the third and fourth interspace (arrows) are large compared with equivalent vessels in the lower zones of the lung. (From Armstong P et al: Imaging of diseases of the chest, ed 2, St Louis, 1995, Mosby.) |

|

| FIG. 23-2 Marked enlargement of the right atrium consistent with tricuspid valve disease in this 86-year-old man. (Courtesy John A.M. Taylor, Seneca Falls, NY.) |

| Condition | Radiographic appearance |

|---|---|

| Mitral stenosis | Large left atrium, right ventricle, and pulmonary trunk; long, straight left heart border; cephalization of pulmonary blood flow; narrowed retrosternal clear space and occasional calcification |

| Mitral insufficiency | Large left atrium and left ventricle, pulmonary edema in severe cases |

| Mitral prolapse (floppy mitral valve syndrome) | Normal (unless regurgitation develops) |

| Aortic stenosis | Large left ventricle, prominent ascending arch, small aortic knob, valve calcification |

| Aortic insufficiency | Large left ventricle, prominent aortic knob |

| Tricuspid stenosis | Large right atrium |

| Tricuspid insufficiency | Large right atrium and right ventricle, dilated superior vena cava and dilated azygous vein |

| Pulmonary stenosis | Large left pulmonary artery, increased left lung vascularity, and large right ventricle |

| Pulmonary insufficiency | Large right ventricle |

CLINICAL COMMENTS

The diagnosis of valvular heart disease is made based on the patient’s clinical history, a physical examination, electrocardiography, chest radiography, and echocardiography. 45 In the past, acquired valvular disease most often was caused by rheumatic fever. This is still the case in underdeveloped countries, but other causes predominate today in developed countries.

• Acquired valvular heart disease presents with a variety of symptoms and findings that vary according to the specific valve involved.

• Radiographic changes in the size of the heart and specific chamber, along with the degree of pulmonary blood flow and presence of calcification, aid in locating the valve involved.

Aortic Aneurysms

BACKGROUND

Aneurysms are circumscribed dilations of an arterial wall. Saccular aneurysms involve part of the circumference of the vessel, whereas fusiform aneurysms involve the entire circumference. If all three arterial layers (the tunica intima, media, and adventitia) are affected, the aneurysm is called a true aneurysm. False aneurysms disrupt arterial walls but are contained by the surrounding connective tissue. A number of conditions, including atherosclerosis, syphilis, mycoses, posttraumatic conditions, congenital conditions, cystic media necrosis, and arteritis, have been named as possible causes of aneurysms (Table 23-2; FIG. 23-3FIG. 23-4FIG. 23-5FIG. 23-6 and FIG. 23-7). Atherosclerosis is the most common cause and usually involves the descending aorta.

| Type | Comments |

|---|---|

| Cystic media necrosis–related | An aneurysm seen in patients with Marfan’s syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, and other diseases in which collagen production is altered; commonly involves the ascending aorta or sinus of Valsalva |

| Atherosclerotic | An aneurysm in which the vasa vasorum is impaired; often demonstrates calcification; commonly affects the aortic arch or descending aorta |

| Congenital | An aneurysm involving a congential discontinuity of arterial wall; commonly involves the sinus of Valsalva |

| Arteries-related | An aneurysm seen in patients with Takayasu’s disease and other diseases involving intimal proliferation and fibrosis; most often affects the ascending aorta |

| Mycotic | A saccular aneurysm caused by infection; does not result in calcification |

| Posttraumatic | An aneurysm involving a vessel tear; common near the ligamentum arteriosum; has a poor prognosis |

| Syphilitic | An aneurysm in which the vasa vasorum has been impaired by Treponema organisms; most commonly affects the ascending aorta and aortic arch |

|

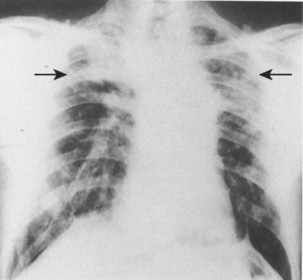

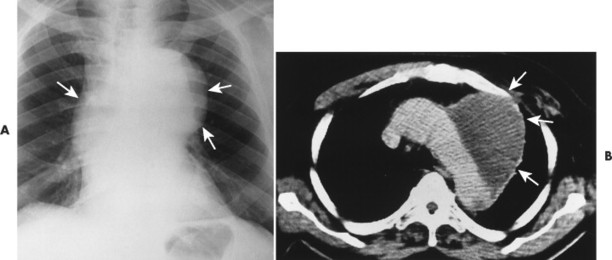

| FIG. 23-3 A and B, Arteriosclerotic aneurysm in the aortic arch (arrows). |

|

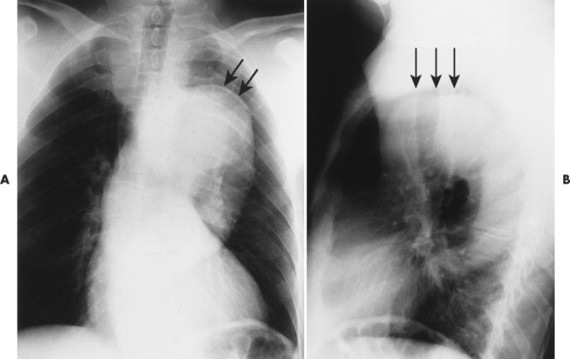

| FIG. 23-4 A, Plain film and, B, angiogram of 21-year-old car accident victim with a traumatic tear of the proximal descending aorta (arrows). (Courtesy Steven P. Brownstein, MD, Springfield, NJ.) |

|

| FIG. 23-5 Angiogram showing an aneurysm in the aortic arch (arrows). (Courtesy Steven P. Brownstein, MD, Springfield, NJ.) |

|

| FIG. 23-6 A, Plain film and, B, computed tomography scan demonstrating an aneurysm in the aortic arch (arrows). |

|

| FIG. 23-7 An 86-year-old man with an enlarged aortic knob (arrow) that is suspicious of aneurysm. Computed tomography is indicated as follow-up. In addition, pneumonia is seen as an air-space pattern in the middle right (reading left) lung field. (Courtesy John A.M. Taylor, Seneca Falls, NY.) |

Aortic dissection occurs when a hematoma in the middle to outer third of the aortic wall longitudinally separates the aortic wall proximally and distally. Hematomas often develop as a result of a vasa vasorum hemorrhage, which is seen in patients with hypertension. The tunica intima may rupture and reconnect the hematoma with its aortic lumen, creating a “double barrel” aorta. A number of classification schemes have been developed to describe the nature and region of aortic involvement (e.g., DeBakey, Stanford).

The radiographic features of an aneurysm are limited to contour changes in the frontal and lateral projections. Although it does not indicate the presence of an aneurysm, vessel calcification provides a means of visualizing distortions of the vessel’s wall. Aortic dissection is suggested by mediastinal widening, cardiomegaly, pleural effusion, and (in rare cases) medial displacement of the calcified plaque more than 1 cm inward from the outer vessel wall of the descending aorta (which is called the calcification sign). 10,11 MRI and computed tomography (CT) provide the best initial and follow-up evaluations of the aorta. 27,56 Angiography may be used preoperatively to better define the vessel.

CLINICAL COMMENTS

The clinical presentation of an aneurysm depends on its size and location; the majority are asymptomatic. 41 Compression of the vena cava (vena cava syndrome), stridor, hoarseness (caused by laryngeal nerve compression), dysphagia, and sternal chest pain may develop in patients who have a large aneurysm mass.

The risk of rupture is related to the size of the aneurysm. Aneurysms of the aortic arch or descending aorta that have a diameter of less than 5 cm rarely rupture. Those exceeding 6 cm have a significant risk of rupturing; 40% of those greater than 10 cm rupture. A patient with a rapidly expanding aneurysm of any size has a poor prognosis. 41

• Aneurysms are localized dilations of all (true aneurysms) or some (false aneurysms) of the arterial wall layers and involve part (saccular aneurysms) or all (fusiform aneurysms) of the vessel’s circumference.

• Although many have no clinical symptoms, large aneurysms are significant and life-threatening.

BACKGROUND

Juxtaductal, or adult type, coarctation of the aorta is a discrete narrowing of the aortic isthmus (the region between the arch and descending aorta) distal to the origin of the left subclavian artery and near the ductus or ligamentum arteriosus. 46 Tubular hypoplasia, or infantile-type coarctation of the aorta, is less common and involves narrowing of a segment of the transverse aortic arch. Coarctation is more common in males and often develops in conjunction with other cardiovascular defects, particularly when it is found in infants.

Although the aorta is narrowed, the collateral circulation typically prevents hypoperfusion of the trunk and lower extremities. In one such collateral path, blood from the subclavian arteries (before the coarctation has developed) enters the internal mammary arteries. It flows to the anterior intercostals and across the intercostal anastomoses, reversing the normal blood flow of the posterior intercostals and causing it to enter the aorta distal to the coarctation that developed. The hypertrophy of the intercostal arteries causes characteristic inferior rib notching.

Pseudocoarctation is kinking of the aorta that commonly is seen secondary to arteriosclerosis in elderly patients.

IMAGING FINDINGS

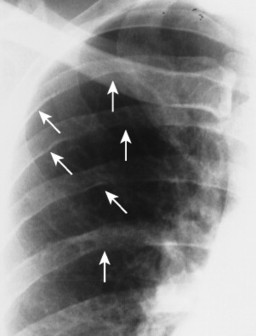

Imaging features of infants with coarctation of the aorta may include cardiomegaly and possibly increased pulmonary vascular markings. In children and adults a characteristic inward deformity of the proximal descending aorta may be present with bulging of the vessel immediately above and below (the “figure 3” sign). This sign is seen uncommonly on images of infants because the aortic arch is difficult to observe. Although not pathognomonic for coarctation, bilateral inferior rib notching is common at the posterior angles of the third through ninth ribs (Fig. 23-8). Rib notching is not seen in the infant. MRI is the modality of choice for further assessment.

|

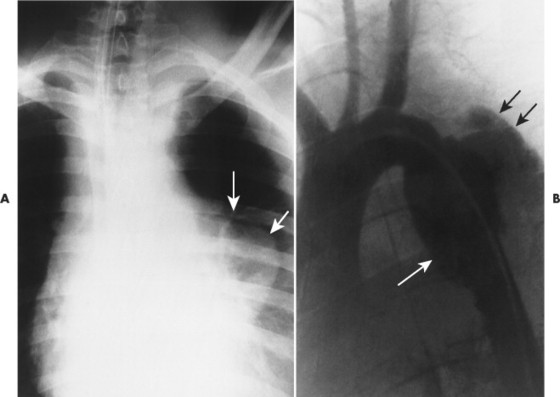

| FIG. 23-8 Notching defect at the lower margin of several ribs in a patient with coarctation of the aorta (arrows). (Courtesy Steven P. Brownstein, MD, Springfield, NJ.) |

CLINICAL COMMENTS

Most symptomatic infants with coarctation of the aorta have concurrent cardiovascular abnormalities (e.g., aortic stenosis, patent ductus arteriosus, ventricular septal defect). 42 Associated cardiac anomalies are uncommon in adults. A blood pressure difference of 20 mm Hg between the arms and legs is strongly indicative of coarctation. 33,42 Treatment involves surgical correction of the deformity. 25

• Coarctation of the aorta is localized postductal (adult-type) or generalized preductal (infantile-type) stenosis of the aortic isthmus.

• Adult-type coarctation of the aorta is characterized by an inward deformity of the proximal descending aorta on frontal projections and typically demonstrates inferior rib notching.

• Infantile-type coarctation of the aorta is more serious than the adult type, usually is associated with other anomalies, and has few common radiographic features.

Congenital Heart Disease

BACKGROUND

Congenital heart disease (Table 23-3) encompasses a wide variety of defects that appear at birth as either isolated anomalies or part of larger complexes. Patients with congenital heart disease are categorized based on the presence or absence of cyanosis. Further subdivisions can be made based on the heart size and pulmonary vascularity.

| *A, Acyanotic; C, cyanotic. | ||||

| †↑, Increased; ↓, decreased: =, normal. | ||||

| ‡Frequency of congenital heart disease cases in children. | ||||

| Defect | Physical appearance* | Pulmonary vascularity† | Frequency‡ | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ventricular septal defect (VSD) | A | ↑ | 25% | A defect that is usually in the fibrous portion of the septum; second most common congenital heart defect (with bicuspid aortic valve defect being the most common); asymptomatic if small30 |

| Atrial septal defect (ASD) | A | ↑ | — | Defect of the ostium secundum; most common congenital defect recognized in adults; often asymptomatic |

| Patent ductus arteriosus | A | ↑ | 15% | Defect in which the ductus arteriosus fails soon after birth, resulting in aorticpulmonary artery shunt |

| Coarctation of the aorta | A | = | 12% | Localized or generalized stenosis of aortic isthmus; results in a large heart in infants and rib notching in adults25,43 |

| Aortic stenosis | A | = | 10% | Valvular or vessel stenosis; usually asymptomatic; in severe cases in infants, results in congestive heart failure |

| Pulmonary stenosis | A | = | 10% | Valvular or vessel stenosis; usually asymptomatic; results in loud systolic murmur and poststenotic dilation of pulmonary trunk |

| Tetralogy of Fallot | C | ↓ | 10% | (1) Obstructed pulmonary outflow tract, |

| (2) ventricular septal defect, (3) right ventricular hypertrophy, (4) aorta overriding interventricular septum18 (in addition, normal heart size); most common congenital heart defect with cyanosis after 1 year of age | ||||

| Pentalogy of Fallot | C | ↓ | — | Defect comprising the tetralogy of Fallot and an ASD; increased heart size |

| Ebstein anomaly | C | ↓ | — | Defect in which a caudally displaced tricuspid valve creates an enlarged right atrium and small right ventricle; increased heart size |

| Tricuspid atresia | C | ↓ | 2% | Absence of tricuspid valve and presence of ASD; increased heart size |

| Total anomalous pulmonary venous return (TAPVR) | C | ↑ | — | Aberrant communication between pulmonary and systemic veins; an ASD is needed for the defect to be compatible with life; “figure 8” or “snowman” configuration of heart shadow |

| Truncus arteriosus | C | ↑ | — | Defect in which a failure of septation forces the pulmonary, systemic, and cardiac arteries to share a single cardiac outlet |

| Transposition of great vessels | C | ↑ | 10% | Defect in which the aorta arises from the right ventricle and the pulmonary trunk arises from the left ventricle; most common cause of neonatal cyanosis; results in a wide heart shadow55 |

| Double outlet right ventricle | C | ↑ | — | Defect in which the aorta and pulmonary trunk arise from the right ventricle; VSD present |

| Single ventricle | C | ↑ | — | Defect in which the ventricular septum is absent and associated defects of the atrioventricular valves are present |

IMAGING FINDINGS

Plain film radiography is used to evaluate pulmonary vascularity, heart size, and configuration of the great vessels (Fig. 23-9). 15,50 Echocardiography, angiocardiography, and MRI are all useful imaging modalities for evaluating congenital heart defects. 13,55

|

| FIG. 23-9 “Figure 8,” or “snowman,” configuration of total anomalous pulmonary venous return. (Courtesy Steven P. Brownstein, MD, Springfield, NJ.) |

CLINICAL COMMENTS

Although congenital heart disease can be so severe that an affected unborn fetus cannot survive, also it can be largely asymptomatic. Many infants with the condition seem to be healthy immediately after birth, but their condition changes as the ductus arteriosus closes and adult circulation begins. Some congenital heart diseases may not appear until adulthood (e.g., floppy mitral valve syndrome).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree