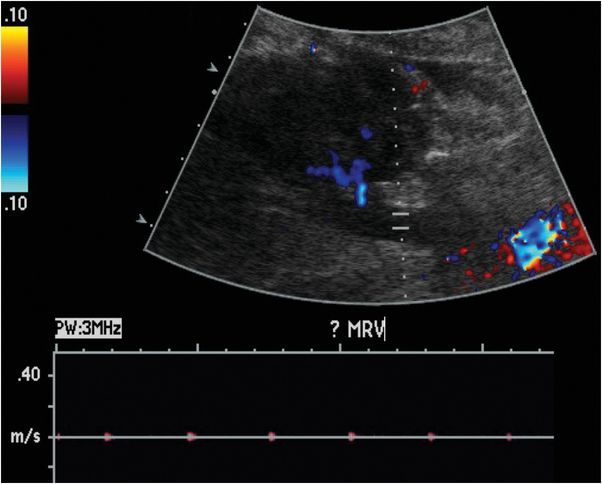

Diagnosis: Renal vein thrombosis in a transplanted kidney

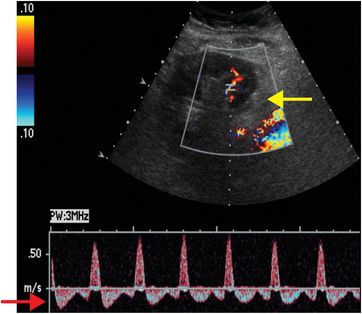

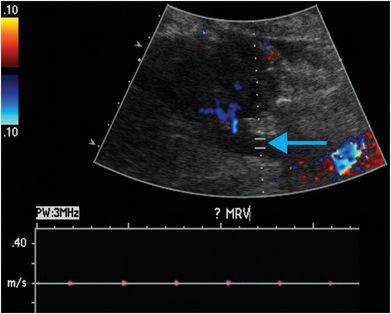

Ultrasound with color Doppler shows a right lower quadrant transplanted kidney, which is edematous and hypoechoic. Spectral Doppler of the lower pole interlobar artery (yellow arrow) reveals elevated intrarenal resistive indices and reversal of flow during diastole (red arrow). No Doppler flow is detected within the main renal vein (blue arrow).

Discussion

Transplanted kidneys are typically placed in an extraperitoneal location in the right iliac fossa with end-to-side or end-to-end anastomosis with the external iliac vasculature.

Donor organs may be cadaveric (cadaveric renal transplant, CRT), from a living related donor (LRT), or from a living nonrelated donor (LNRT). As a donated organ, the left kidney is preferred for its longer renal vein that is easier to anastomose. The type of graft that is available for harvest dictates the type of arterial anastomosis.

From cadaveric donors, a Carrel patch (a small piece of aorta around the origin of the renal artery) may be harvested along with the graft, and anastomosed to the recipient external iliac artery in an end-to-side fashion. The preferred method for restoring ureteral drainage is ureteroneocystostomy, in which the ureter is anastomosed directly to the urinary bladder. If the cadaveric donor is under 5 years of age, both donor kidneys may be transplanted into a single recipient using the donor aorta and vena cava for vascular anastomosis (“en bloc” pediatric transplant).

Early recognition of complications is essential for graft and patient survival.

In evaluating patients who have had a renal transplant, a systematic approach should be utilized. Complications may be categorized by affected anatomic site: the transplant perinephric space, the renal parenchyma, the urinary collecting system, and the renal vasculature.

When sonographic findings are nonspecific, the clinical and laboratory data are often very helpful in narrowing the differential diagnosis; however, biopsy may ultimately be necessary for a more definitive diagnosis.

Perinephric space: postoperative fluid collections containing pus, blood, lymphatic fluid, or urine are common in the transplant perinephric space. Ultimately, these collections may require sampling for diagnosis, as the sonographic appearances overlap. Clinical significance depends on size, composition, location, and degree of mass effect.

Renal parenchyma: parenchymal abnormalities have a nonspecific sonographic appearance. Infarct, rejection, and focal pyelonephritis can appear as focal areas of increased or decreased echogenicity.

Urinary collecting system: complications include urine leak, urinoma, urinary obstruction, and urinary calculi.

Renal vasculature: renal artery occlusion and renal vein thrombosis are devastating complications of the early postoperative period that can rapidly lead to graft loss. Delayed complications include renal artery stenosis and post-biopsy arteriovenous fistulas and pseudoaneurysms. Renal vein thrombosis is more common than renal artery occlusion and typically occurs in the first few days after transplant. Etiologies include suboptimal technique, compression of the renal vein by a fluid collection, and hypovolemia. The affected kidney may appear enlarged and hypoechoic, with lack of Doppler signal in the renal vein. The intraparenchymal renal artery branches are compressed, and spectral Doppler shows increased resistance, often with reversal of flow away from the kidney during diastole (ordinarily, flow is toward the kidney in all portions of the cardiac cycle). Reversal of diastolic flow can also be seen in severe rejection or acute tubular necrosis, but the finding of absent venous flow is diagnostic for renal vein thrombosis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree