Cholelithiasis (Gallstones)

Colon Polyps

Colorectal Carcinoma

Crohn’s Disease

Diverticular Disease

Hiatal Hernia

Pancreatic Lithiasis

Peptic Ulcer Disease

Ulcerative Colitis

Radiographic Anatomy of the Gastrointestinal Tract

A thorough understanding of the normal plain film appearance of the gastrointestinal tract is critical when evaluating for the presence of serious conditions that may affect this system. For example, swallowed air within the stomach has a different appearance than gas within the small bowel or colon. Table 30-1 reviews the plain film appearance of the gastrointestinal tract.

| Organ | Visibility | Location | Retro peritoneal versus intraperitoneal | Fixed versus mobile | Appearance specifics | Plain film abnormalities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Esophagus | Air occasionally visible in cervical region | Anterior and left of spine from laryngopharynx to diaphragm | Not applicable | Fixed | None on plain film | Abnormalities including dilation or neoplasm may present as posterior mediastinal mass (hiatal hernia) |

| Stomach | Air in fundus on upright with inferior fluid level, spreads to body of stomach and may outline rugae on supine image | Magenblase immediately inferior to left lung base on upright image; should not extend to midline or lateral body | Intraperitoneal | Fixed proximal and distal; mobile body | None on plain film | Displacement of magenblase laterally suggests hepatomegaly |

| Duodenum | Occasional air in bulb | Right upper quadrant medially | Retroperitoneal (most) | Fixed | None | None |

| Small bowel | Occasional small segment air-filled | Most of abdomen; jejunum primarily left upper quadrant and middle lower ileum | Intraperitoneal | Mobile | Small, thin mucosal folds | Long segments air-filled; dilated air-filled (>3 cm) |

| Cecum | Fluid feces and gas bubbles mixed | Right lower quadrant | Intraperitoneal | Mobile, usually right lower quadrant location | None | Distention (>10 cm risk of rupture); volvulus (“coffee bean” sign) |

| Appendix | May be visible gas in appendix | Considerable variation, although usually in right lower quadrant | Intraperitoneal | Can move with the cecum | None | Normal or may show slight distention of adjacent ileum; possible appendicolith |

| Ascending and descending colon | Visible gas in haustra | Ascending along right flank; descending along left flank | Retroperitoneal | Fixed | Widely spaced, thick mucosal folds Lateral margin of both should be within 2 to 3 mm of adjacent flank stripe (fat plane medial to abdominal muscle wall). Splenic flexure should be most superior portion of colon. | Dilation |

Cholelithiasis (Gallstones)

BACKGROUND

The incidence of gallstones in patients in the United States approaches 20% of men and 35% of women by the age of 75 years; 24 thus, gallstones exhibit a greater prevalence in women and in older age groups. Obesity and certain diseases also are associated with the development of gallstones (Table 30-2).

| Associated factors | Comments |

|---|---|

| Obesity | Rapid weight loss resulting in increased risk of symptomatic gallstone formation |

| Increasing age | Associated with increased cholesterol secretion |

| Northern European ethnic group | Associated with increased cholesterol secretion |

| Estrogen replacement therapy and oralcontraceptive use | Increases biliary output of cholesterol and also reduces synthesis of bile acid in women |

| Pregnancy | Associated with increased risk of gallstones and symptomatic gallbladder disease |

| Sickle-cell anemia or other hemolytic conditions | Hemolysis increases bilirubin excretion |

| Crohn’s disease | Disease of the terminal ileum causing disruption of bile acid reabsorption |

IMAGING FINDINGS

Ultrasonography generally is the preferred imaging modality for evaluating patients for possible gallstones or biliary duct obstruction. Gallstones produce hyperechoic foci with acoustic shadowing, and mobility of the stone usually is apparent (Fig. 30-1). 5,15 The patient should fast for 4 or more hours because these stones can be missed in a contracted gallbladder. 25

|

| FIG. 30-1 Choleliths. Ultrasound image shows multiple echogenic foci within the gallbladder lumen (arrows) with posterior acoustic shadowing (curved arrows). (Courtesy John A.M. Taylor, Seneca Falls, NY.) |

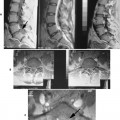

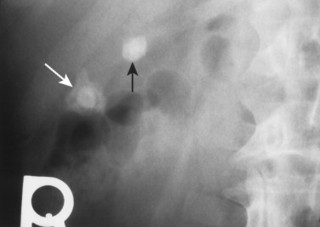

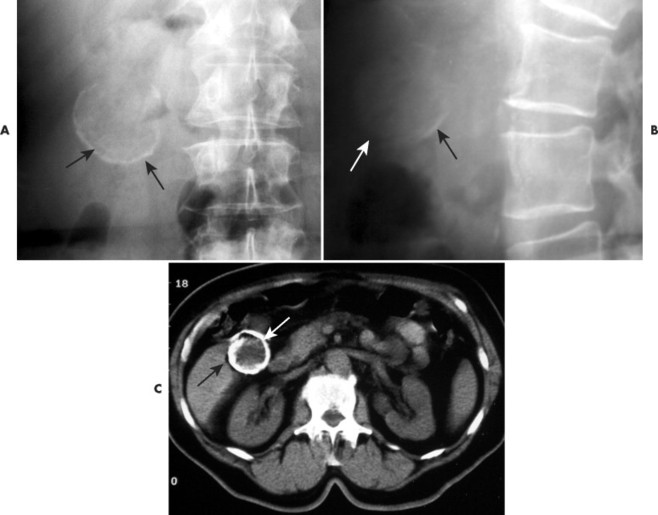

These stones may be imaged incidentally on plain film radiographs even in asymptomatic patients, but only 10% to 15% of them contain enough calcium to be visible (FIG. 30-2FIG. 30-3 and FIG. 30-4). 11,31 Oral cholecystography (OCG) requires the patient to take an oral contrast agent, which is absorbed from the bowel, excreted by the liver, and concentrated in the gallbladder (except when the gallbladder cystic duct is blocked or sometimes when the gallbladder is inflamed). The gallbladder also is not seen in cases of a lack of absorption or significant liver damage.

|

| FIG. 30-2 Choleliths. Two laminated and faceted calculi in the gallbladder characteristic of concretion calcifications (arrows). |

|

| FIG. 30-3 Oral cholecystographic appearance of gallstones. A, Oral cholecystogram with the patient in the recumbent position demonstrates several nonopaque stones within the gallbladder (arrows). B, With the patient in the upright position, the stones float just above the fundus (arrows). (Courtesy John A.M. Taylor, Seneca Falls, NY.) |

|

| FIG. 30-4 Gallstones appearing as radiodense calculi of the right upper abdominal quadrant on, A, an anteroposterior and, B, lateral lumbar projection; and, C through E, in three other patients (arrows). |

OCG does demonstrate most gallstones, but since the development of ultrasound to accomplish this task, it is thought by some to be most useful for providing information about the functional status of the gallbladder (see Fig. 30-3). 7 However, the clinical usefulness of this is still controversial.

Uncommonly, the noncontrasted gallbladder forms a radiodense “milk of calcium” bile that mimics the gallbladder’s appearance during OCG (Fig. 30-5). This phenomenon is thought to develop from chronic obstruction of the cystic duct by one or more gallstones in patients with chronic cholecystitis. The duct obstruction leads to decreased gland function, bile stasis, and radiographic visible accumulations of a radiodense calcium carbonate in viscous intraluminal bile. Review of the patient’s history to exclude any recent intake of contrast material (oral or intravenous) must be accomplished before the milk of calcium bile diagnosis can be made. On radiographs, the fluid is found in the gravity-dependent portion of the gallbladder. The ultrasound appearance is not consistent because the composition of the milk of calcium bile varies from a semisolid to fluid suspension.

|

| FIG. 30-5 Milk of calcium bile. Multiple gallstones are noted in the lower portion of the gallbladder. The stones are contrasted by an opaque fluid of calcium carbonate, known as milk of calcium bile. (Courtesy Ian D. McLean, LeClaire, IA.) |

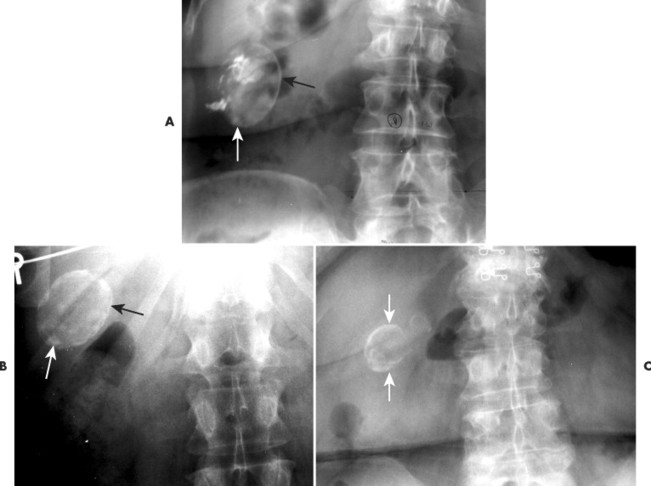

“Porcelain gallbladder” describes extensive calcification of the wall of the gallbladder; also known as calcifying cholecystitis or cholecystopathic chronica calcarea (Figs. 30-6 and 30-7). Specifically the term refers to the blue-greenish discoloration and brittle condition of the gallbladder observed at surgery. A porcelain gallbladder typically is found incidentally on plain film studies. Patients generally are asymptomatic and more commonly are women (5:1 ratio). Concurrent gallstones are usual. A porcelain gallbladder is associated with higher incidence of adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder, typically warranting prophylactic excision.

|

| FIG. 30-6 Porcelain gallbladder. A, Anteroposterior and, B, lateral plain films exhibit curvilinear radiodense shadows in the right upper abdominal quadrant that correspond to partial calcification of the wall of the gallbladder. C, On computed tomography without contrast, the circumference of the gallbladder is calcified. Gallstones are not present (arrows). (Courtesy Kevin Paustian, Durant, IA.) |

|

| FIG. 30-7 A through C, Porcelain gallbladder in several patients (arrows). The finding of a porcelain gallbladder typically warrants surgical excision because of the approximately 20% associated increased risk of developing gallbladder carcinoma. |

CLINICAL COMMENTS

Cholelithiasis usually is discovered incidentally during other studies. In the first 5 years after diagnosis, only approximately 10% of patients experience symptoms resulting from gallstones. 31 Right upper quadrant pain is the most commonly reported symptom. 31 The pain usually is steady, lasting for several hours. Radiation to the lower abdomen, back, or tip of the right scapula is not uncommon; vomiting may occur. 5

Complications seen with gallstone disease include cholecystitis, choledocholithiasis, pancreatitis (migration of a stone to the distal common duct where the pancreatic duct enters), cholangitis, stone perforation of the duodenum or colon, and gallstone ileus (Table 30-3). 2,3,5,19,31 Symptomatic gallbladder disease may require surgical intervention if nonsurgical techniques such as lithotripsy (using strong ultrasound waves to break up the stone) are ineffective, unsuitable, or unavailable. 31

| Complications | Comments |

|---|---|

| Acute cholecystitis | May remit temporarily, but sometimes progresses to gangrene and perforation |

| Choledocholithiasis | Gallstones obstructing the common bile duct |

| Cholangitis | Infection of the bile ducts following obstruction possible |

| Acute pancreatitis | Probably secondary to transient obstruction of the main pancreatic duct |

| Gallstone ileus | Follows perforation of the duodenum or bowel by gallstone; classic plain film triad: small bowel obstruction, biliary tract air, and an opaque concretion in the small bowel |

• The prevalence of cholelithiasis increases with age.

• It is more common in women.

• Obesity is a risk factor.

• Symptoms vary and clinical correlation is required.

• Plain film radiography plays a minor role.

Colon Polyps

BACKGROUND

Colon polyps are found in up to 12% of the population. 33 The adenomatous polyp is considered the precursor to colorectal cancer. 16 Therefore detection of colonic polyps is extremely important. The incidence of malignancy increases with increased size of the polyp (Table 30-4). Most polyp development is incidental, but polyps also appear as part of familial polyposis syndromes (not common). Table 30-5 reviews the characteristics of several polyposis conditions.

| 5 mm or less | 5 mm to 10 mm | 10 mm to 20 mm | More than 20 mm |

|---|---|---|---|

| <0.5% | 1% to 2.5% | 10% | 46% |

| Complications | Comments |

|---|---|

| Nonfamilial adeonomatous polyps | Present in 30% of adults over 50 years of age; malignancy correlates with polyp size, villous features, and degree of dysplasia |

| Familial adenomatous polyposis | Autosomal dominant; it begins to appear between ages of 10 and 35 years; colon cancer usually occurs by age 50 |

| Gardner syndrome | Variant of familial adenomatous polyposis; it is characterized by extraintestinal osteomas, fibromas, and desmoid tumors |

| Familial juvenile polyposis | Autosomal dominant; most common—colon |

| Peutz-Jehgers syndrome | Autosomal dominant; mucocutaneous pigmented macules appear on lips, buccal mucosa, and skin; 50% of patients develop malignancies in gastrointestinal and nonintestinal organs |

| Turcot syndrome | Autosomal recessive; central nervous system neoplasm |

IMAGING FINDINGS

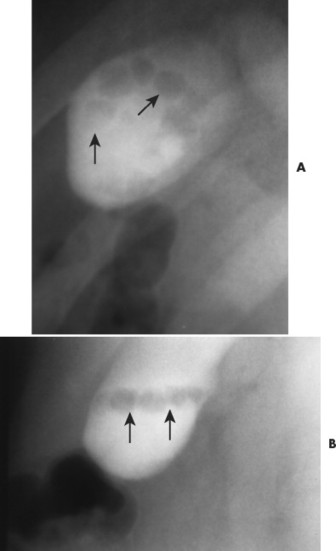

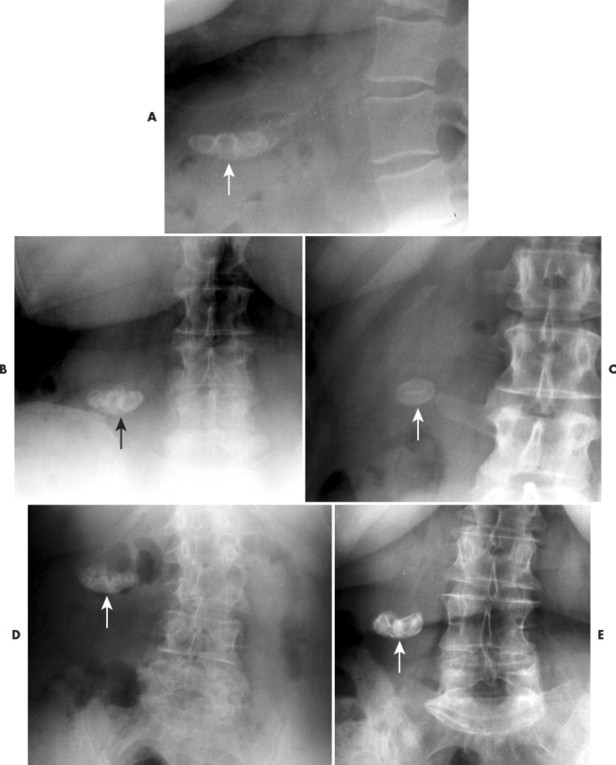

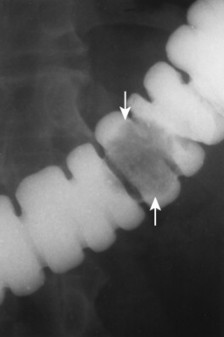

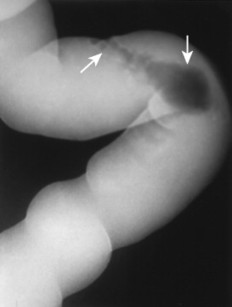

Barium examination and endoscopy are the most important methods for detecting polyps. 32 Polyps appear as discrete masses, sessile or pedunculated, which protrude into the lumen of the gut (FIG. 30-8FIG. 30-9 and FIG. 30-10). Recent investigations report up to 98% accuracy in identification of polyps by double-contrast barium enema. Older studies report less accuracy, but the accuracy depends on the meticulousness and quality of the exam. Lesions smaller than 1 cm in diameter are more difficult to detect.

|

| FIG. 30-8 Sessile polyp. Filling defect of a sessile-based polyp is well demonstrated (arrows). |

|

| FIG. 30-9 Polyp with stalk. A pedunculated polyp is visualized within this contrast-filled bowel (arrows). |

|

| FIG. 30-10 Polyp with stalk. Double-contrast (air and barium) study reveals a pedunculated polyp (arrows). Diverticulae are seen with this study also (crossed arrow). |

In general the inner margin of a polyp appears sharper than the outer margin because it is an intraluminal mass surrounded by barium. On occasion a diverticulum coated with barium and filled with air can mimic a polyp on one or more x-rays, but with meticulous evaluation it should not be misdiagnosed.

CLINICAL COMMENTS

Most patients with multiple small polyps or even small carcinomas have no overt symptoms. Chronic occult blood loss from polyps may lead to iron deficiency. Occasionally, symptoms from large polyps are related to complications such as intussusception or colonic obstruction. 32 Polyps measuring 1 cm or larger definitely should be removed and histologically examined, although some experts believe even smaller ones should be removed also.

• Colonoscopy and barium enema are two possibly equal modalities in evaluating the colon for polyps.

• Adenomatous polyps may be a precursor to colon cancer.

• The incidence of malignancy increases with increased size of the polyp.

Colorectal Carcinoma

BACKGROUND

Colorectal cancer is second only to lung cancer in men and breast and lung cancer in women as a cause of death. 38 The incidence of colorectal cancer increases after 35 to 45 years of age; however, high-risk persons (Table 30-6) develop colorectal cancer at a much younger age. 26,34 Most colorectal cancers are thought to arise from malignant transformation of an adenomatous polyp. 34

| Risk factors | Comments |

|---|---|

| Familial polyposis | 100% risk of cancer if untreated |

| Gardner’s syndrome | Characterized by precancerous colorectal polyps; associated with osteomas, fibromas, soft-tissue desmoids, and lipomas |

| Ulcerative colitis | Patients with long-standing and extensive ulcerative colitis at high risk |

| Crohn’s disease | Risk not as high as for those with ulcerative colitis |

| Family history | Positive family history for colorectal cancer or polyps |

| Hereditary cancer of multiple anatomic sites |