AB2 Pneumoperitoneum

AB2a Most Common Causes of Pneumoperitoneum

AB2b Plain Film Technique for Detection of Pneumoperitoneum

AB2c Signs of Pneumoperitoneum on Supine Abdominal Films

AB2d Pseudopneumoperitoneum

AB3 Abnormal Localized Intraperitoneal Gas Collections

AB4 Pneumoretroperitoneum

AB5 Abnormal Bowel Gas Resulting from Obstruction

AB6 Ascites

AB7 Enlarged Organ Shadows

AB7a Hepatomegaly

AB7b Gallbladder Enlargement

AB7c Spleen Enlargement

AB7d Gastric Distention

AB7e Right Kidney Enlargement

AB7f Left Kidney Enlargement

AB7g Adrenal Enlargement

AB8 Abdominal Masses

AB8a True Abdominal Massses

AB8b Pseudomasses

AB9 Diseases of the Gallbladder

AB10 Vascular Calcifications

AB11 Miscellaneous Radiopacities and Abdomen Artifacts

Numerous pathologic processes in the abdomen may cause soft-tissue calcification. A pattern approach that evaluates the morphologic features, location, and mobility of an abnormal opacity often provides sufficient information for a definitive diagnosis or at least narrows the etiologic considerations to a few possibilities. 3 Almost all abdominal calcifications fall into four major morphologic categories. Each one of the four categories possesses characteristic roentgen features based on shape, border sharpness, marginal continuity, and internal architecture. 3 The four morphologic categories are concretions, conduit wall calcification, cystic calcification, and solid mass calcification (Table 32-1). 3 A concretion represents calcification within the lumen of a vessel or hollow viscera. The most common of these are listed in Table 32-2. Concretions typically do not pass through vascular or visceral walls; therefore they seldom are seen outside their expected locations. Calcification with the wall of fluid-containing hollow tubes (e.g., parts of the urinary tract, the pancreatic ducts, vas deferens, biliary ductal system, and arteries and veins) is known as conduit wall pattern. Calcification within the wall of a hollow mass is characteristic of the cystic morphologic category. Lastly, the solid mass calcification can be found anywhere within the abdomen and may be central or peripheral, adjacent to or within organs, or in the intraperitoneal or retroperitoneal spaces.

| Morphology | Shape | Border | Margin | Internal appearance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concretion (stone) | Varied (round or oval, faceted); occasional unique shape such as star-shaped bladder calculi or “staghorn” calculus | Sharp, clearly defined; may occasionally have irregular bulges | Continuous; if outer perimeter is incomplete, it is unlikely a stone | Varied Multiple laminations (unequivocal indication of concretion) Homogenously dense Single central lucency Outer margin is dense and continuous with lucent internal appearance |

| Conduit | Tubular, tracklike appearance when viewed in profile; ringlike appearance when viewed en face | May be indistinct | Discontinuous, irregular | None; presence of internal radiopacity suggests another morphologic category |

| Cystic | Round or oval; may be compressed on one side; shape depends on location | Smooth, curvilinear rim of opacification | Rim calcification may be continuous or interrupted; short arcs may be only visibly calcified portion | Surfaces with extensive calcium deposition that are not tangential to x-ray beam may simulate internal matrix (masslike) calcification; interior calcifications less dense than marginal calcifications |

| Mass | Varied | Irregular calcified border; occasionally, the border is more densely calcified than interior resembling cyst | Interrupted; margins typically appear notched or slightly angulated | Extensive interior calcification; mottled densities with scattered radiolucencies; flocculent calcification superimposed on lucent background |

| Site | Comments |

|---|---|

| Pelvic veins (phleboliths) | Represent calcification within preexisting venous thrombi; typical appearance is round opacity with a central or slightly eccentric single lucency |

| Gallbladder (choleliths) | Circumferential laminations are encountered frequently |

| Urinary tract (nephroliths) | Ureteral calculi are often angular; bladder stones are most often smooth and laminated; renal calculus occupying the pelvicaliceal system may have an appearance of a “staghorn” distinguishing it from other abdominal radiopacities |

| Prostate | Predominantly within elderly men |

| Appendix (appendicolith, fecalith) | Usually encountered in younger patients; appendicoliths often are laminated; essentially considered a surgical indicator |

| Pancreas | Typically present as discrete opacities that cross the midline at the level of the L1-2 vertebral bodies; discrete opacities present in head of pancreas alone (25% of cases) |

Several limitations of classification according to radiographic morphology exist. When a calcification is small, it is difficult to categorize. Furthermore, faint calcification cannot be classified if no information about margins or internal matrix can be ascertained. 3

The following is a brief presentation of each of the four major morphologic categories (AB1a through AB1d) with the most common etiologic considerations.

AB1a. Concretions

A concretion (also called a stone or calculus) is a calcified mass that forms in a tubular or hollow structure such as the lumen of a vessel or hollow viscus. A fairly constant appearance of concretions is a sharp, clearly defined external margin that almost always is continuous. 3 This continuity may help differentiate a concretion in a hollow viscus (e.g., renal pelvis, gallbladder, urinary bladder) from a calcified cyst. Discontinuity of the outer margin makes a diagnosis of a stone unlikely. The internal architecture of concretions may vary in appearance. Concretions may have concentric laminations, contain a slightly eccentric area of lucency, or be homogenously dense. On occasion a concretion’s outer margin is dense and continuous with a lucent internal appearance. Generally concretions are seen in association with anatomic structures and do not pass through the vascular or visceral wall. Concretions appearing outside of common, expected anatomic locations are unusual.

| CONCRETION | COMMENTS |

|---|---|

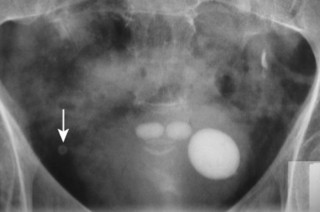

| Appendicolith (FIG. 32-1) | Frequently associated with current or future appendiceal perforation, especially in children; 18 it is seen most commonly in the right lower quadrant but location may vary. |

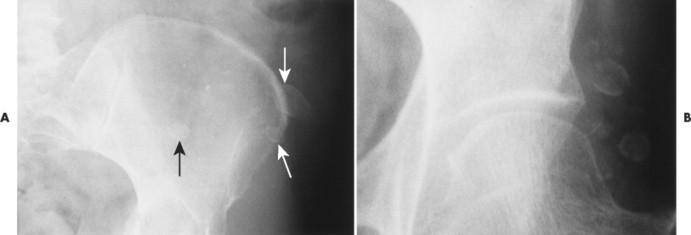

| Cholelithiasis (FIG. 32-2) [p. 1287] | Ten to fifteen percent are calcified and therefore visible on plain film; 30,62 cholelithiasis occurs more frequently in elderly and obese people, predominantly in women; 30 typically cholelithiasis occurs in the right upper quadrant, but location may vary. |

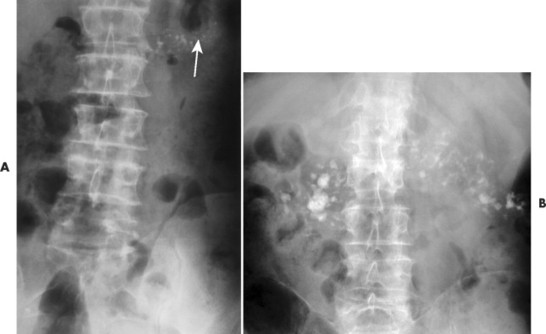

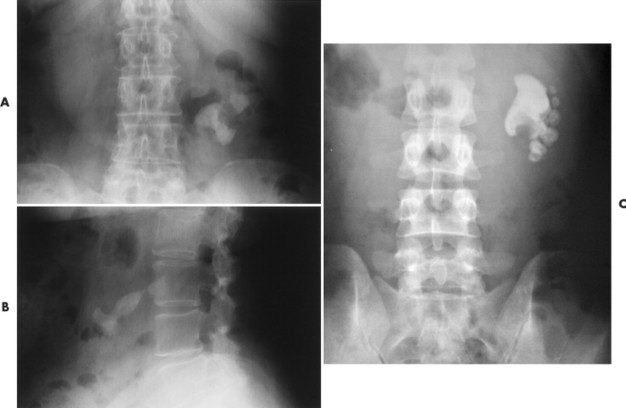

| Pancreatic calculi (FIG. 32-3) | Most commonly associated with chronic pancreatitis secondary to alcoholism; 61 the typical appearance is multiple, tiny, dense, discrete opacities that cross the midline at the level of L1-2. |

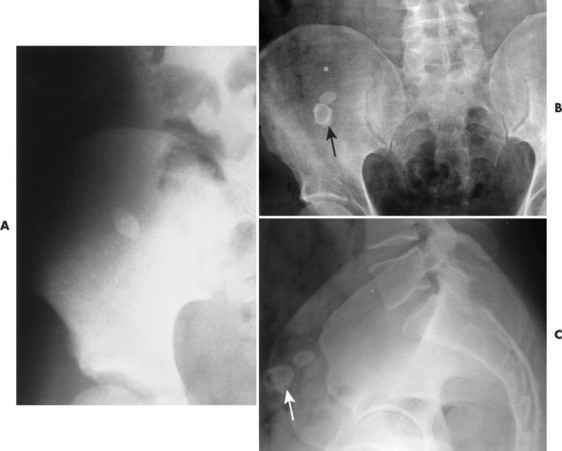

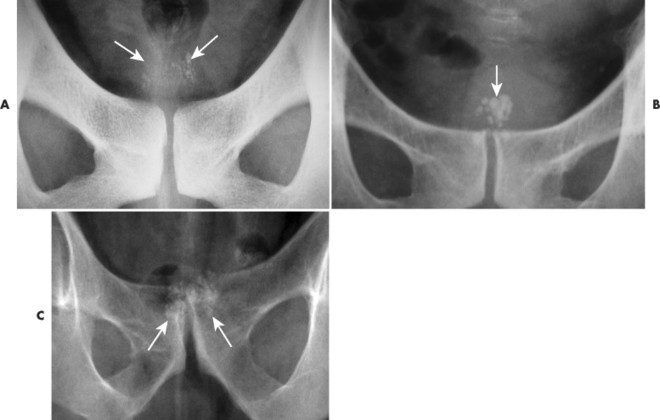

| Phleboliths (FIG. 32-4) | Most commonly encountered calcification in pelvis; 3 they are frequently multiple and bilateral; sometimes a concentric or slightly eccentric interior lucency occurs; they can be confused with urinary tract stones; should not appear midline; collections of phleboliths outside the area of the pelvic bowl veins may indicate the presence of a soft-tissue hemangioma. |

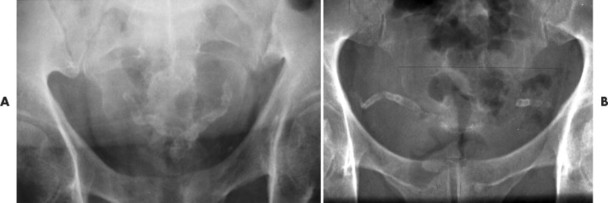

| Prostatic calculi (FIG. 32-5) | Multiple concretions of varied sizes clustered behind pubic symphysis in men usually more than 40 years of age; 3 this condition results from prior prostatitis; prostatic calculi often are asymptomatic. |

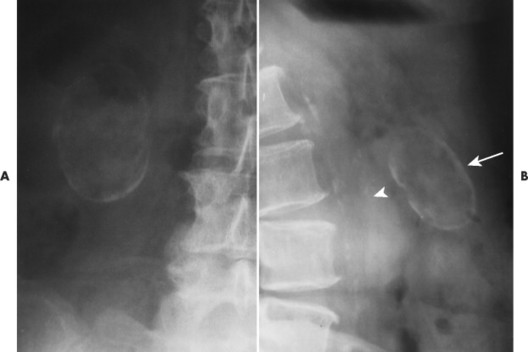

| Urinary tract calculi (FIG. 32-6FIG. 32-7 and FIG. 32-8) | May be seen in the renal calyces or pelvis, ureters, and bladder; they are uncommon in the urethra; 52 sometimes urinary tract calculi are associated with conditions producing hypercalcemia or hypercalciuria. 3 |

|

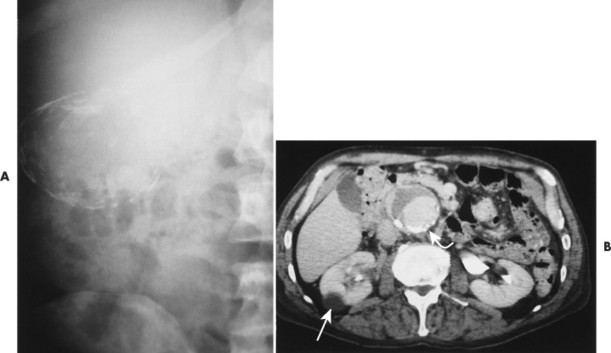

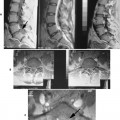

| FIG. 32-2 Cholelith. A and B, Laminated gallstone with continuous outer margin typical of a concretion (arrow) in different patients. |

|

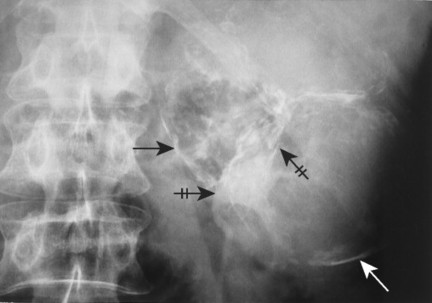

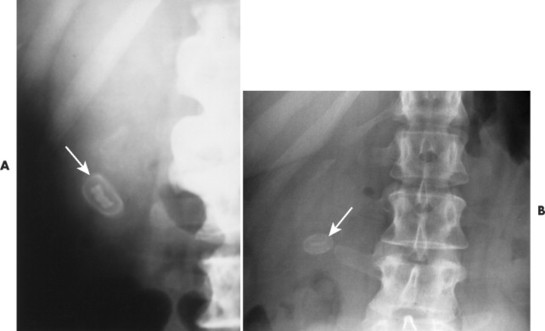

| FIG. 32-7 Ureteral stones. Intravenous urogram demonstrates multiple small opacities located within the lower segment of the ureter (arrows). |

Conduits are channels or tubular structures through which fluids are conducted. 3 Conduit wall calcifications are confined to only the tubular walls, which are seen radiographically as parallel, linear opacities or, when seen on end, as ringlike calcifications. 3 Therefore any internal radiopacity indicates another class of calcification.

The calcification in conduit walls is not homogeneous. The most common site is in the walls of arteries, where one sees interrupted but basically linear calcifications. 3 This feature helps differentiate them from concretions, which usually have a continuous calcified external margin. The calcification also can outline a vessel’s branching pattern. 3

| LOCATION | COMMENTS |

|---|---|

| Aorta and iliac arteries (FIG. 32-9) | Occurs mostly as a result of atherosclerosis; patients younger than 40 years of age are rarely affected; this may be associated with smoking or diabetes; patients can be hypertensive or have coronary artery disease. |

| Renal arteries | Arise from abdominal aorta at or near L1 and usually extend laterally or infralaterally; calcification occurs primarily as a consequence of atherosclerosis or diabetes; 2,59 this often is accompanied by aortic calcification. |

| Splenic artery (FIG. 32-10) | Frequently calcifies and has a characteristic serpentine course in the left upper quadrant. |

| Iliac veins and inferior vena cava | Veins not subjected to either high pressure or pulsatile flow and are relatively protected from the risk of intimal layer damage (see Figs. 32-4 and 32-68). 3 |

| Gallbladder wall (FIG. 32-11) | Also known as porcelain gallbladder, can resemble a large gallstone; a significant percentage of these patients also develop gallbladder cancer, usually adenocarcinoma. * Typically prophylactic surgery is indicated. |

| Vas deferens (FIG. 32-12) | Most often in diabetic patients, rarely secondary to infection; 11,23,35 most often it is bilateral, curved, symmetric, and parallel to the pubic rami. |

| *References 5, 10, 17, 33, 44, 51 | |

|

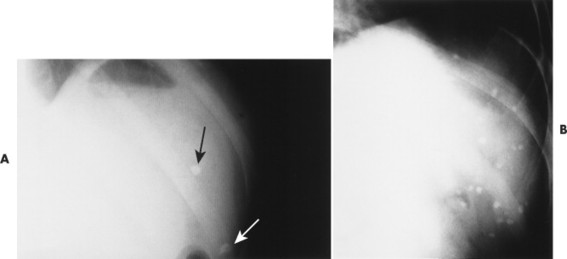

| FIG. 32-10 Splenic artery calcification. A convoluted and tubular appearance is typical of the splenic artery (arrows). |

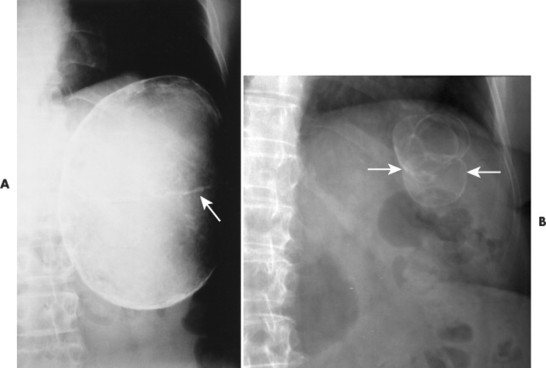

Calcium deposition in the wall of an abnormal fluid-filled structure defines cystic calcification. 3 Calcium around the surface of a tumor occasionally mimics this appearance. Examples of cystic calcification include epithelial-lined cysts, pseudocysts that have fibrous integument, and arterial aneurysms. Calcification shows up as a smooth, curvilinear rim of opacity. 3 This rimlike appearance usually is larger than that of conduit wall calcification; however, calcification may be interrupted in spots in both types, appearing as an incomplete circle. Single, incomplete calcified margins likely represent a cystic density, in contrast to a concretion, in which one should expect a continuous margin of calcification. 3 The external border of the cyst usually is smooth, whereas the internal aspect is irregular, reflecting the interface with the contained fluid. 3 In contrast to a solid mass type of pattern, the outer margin of a cystic structure usually exhibits a relatively well-defined margin. Adjacent organs or vessels may be displaced or distorted by either solid masses or cystic structures.

| CYST | COMMENTS |

|---|---|

| Left upper quadrant (above L3) | |

| Spleen(FIG. 32-13) | Two thirds of splenic cysts caused by Echinococcus granulosis (rare in the United States); 60 other possibilities include hemorrhagic and serous cysts, usually secondary to trauma; 13 cystic changes may be secondary to subcapsular hematoma and metastatic mucinous adenocarcinoma of the ovary; 47 occasionally an aneurysm of splenic artery may mimic a cyst; see also the Renal and Adrenal sections that follow. |

| Right upper quadrant (above L3) | |

| Liver | Rare hepatic cysts except those associated with Echinococcus granulosis; occasionally gallbladder carcinoma calcification can reside high and inside the liver. 7,21 |

| Right or left upper quadrant | |

| (FIG. 32-14) | Benign and malignant neoplasms of the kidney and renal cysts; renal cysts are more common with advancing age, but usually they do not calcify; 31,34,50 renal artery aneurysm and subcapsular hematoma also may present as cystic calcifications. |

| Adrenal(FIG. 32-15) | Infrequent; pseudocysts are the most common cysts to calcify; 46 calcified cystic pheochromocytomas and other benign and malignant tumors are rare. 20,54,68 |

| Midabdomen | |

| Pancreas | Rare calcification of the wall of a pancreatic pseudocyst; 36 cystic calcifications may be seen in benign and malignant tumors. 19 |

| Right lower quadrant (below L3) | |

| Appendix | Mucocele calcification rarely appears as a calcified cyst; it occurs primarily in middle-aged persons and is slightly more common in men. 14 |

| Left lower quadrant (below L3) | Least likely of the abdominal regions to contain calcific densities; when present, they are likely to be ureteral stones, vascular densities, and leiomyomas; cystic calcifications are especially rare. |

| Pelvic bowl | |

| Bladder | Schistosomiasis of the bladder, worldwide, is the most common cause of mural calcification and is seen as a thin, continuous curvilinear calcification of cyst type; it is rare in the United States. 65 |

| Ovary | Most common ovarian lesion: cystic teratoma (dermoid cyst); 67 about 10% of cystic teratomas show calcification of cyst type; 12,67 benign cystadenomas and cystadenocarcinomas may appear as curvilinear calcifications of cystic type; 45 any cystic calcification in this area must be considered a possible malignancy unless proved otherwise. |

| Any location | |

| Mesentery and omentum | Cysts resulting from inflammation, trauma, or congenital rests; 3 they can move on sequential films; they are located anterior to pancreas, kidney, spleen, and adrenal glands. |

| Cystic calcifications that cross midline | |

| Aorta(FIG. 32-16) | Abdominal aortic aneurysm: most common abnormality with the radiographic appearance of the cystic calcification in this location. 3 |

This category comprises the most diverse presentation of the four. Irregularly calcified borders and complex internal architecture are characteristic of solid mass calcification. 3 Prominent but irregular and inhomogeneous calcification in the more central portion of the mass and discontinuity of the outer border are encountered frequently. 3

| MASS | COMMENTS |

|---|---|

| Left upper quadrant | |

| Spleen(FIG. 32-17) | Splenic densities most often resulting from calcium deposition in granulomas, often from histoplasmosis if multiple or occasionally from tuberculosis. 22,58 Frequently they have the morphologic appearance of concretions. |

| Right upper quadrant | |

| Liver | Most common universal cause of solid calcifications: tuberculosis and histoplasmosis; 1,16 calcified metastases (usually from colon and ovary) and benign neoplasms, such as cavernous hemangioma, may cause solid calcifications. 40 |

| Right or left upper quadrant | |

| Adrenal(FIG. 32-18) | In the adult, a normal-sized adrenal gland with calcification may be seen secondary to tuberculosis, |

| Addison’s disease, and old neonatal hemorrhage; solid adrenal calcification in an enlarged gland may result from cortical carcinoma; adenomas rarely calcify. 6 | |

| Renal(FIG. 32-19) | Hypernephromas make up 90% of all solid mass type of calcification involving the kidney; 15 among inflammatory diseases, tuberculosis most frequently shows calcification; 64 solid mass calcification can occur in other primary malignancies, metastases (rare), and hamartomas. 53 |

| Midabdomen | |

| Pancreas(FIG. 32-20) | Pancreatic cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma solid mass calcification varying from a large stellate to closely aggregated solid masses to scattered clumps. 28,48 |

| Pelvic bowl | |

| Bladder | Detectable calcifications seen in only 0.5% of bladder tumors; 43 bladder calcification is rare with urinary tuberculosis; 27 schistosomiasis can calcify but is rare in the United States. |

| Uterine(FIG. 32-21) | Coarse, granular calcifications resembling popcorn or cauliflower developing within necrotic areas of uterine leiomyoma (common) and leiomyosarcoma (rare). 56 |

| Ovary | Two thirds of all ovarian malignancies: papillary serous cystadenocarcinomas that may calcify at the primary site and in metastatic deposits; 8,63 the calcification, known as psammomatous calcification, can vary from a flocculent, sharply demarcated focus to a less well-defined density and sometimes are found throughout the abdomen. |

| Any location | |

| Intestinal tract | Adenocarcinomas or colloid carcinomas of the intestinal tract with characteristically mottled, speckled, or granular pattern calcification; however, calcified small bowel tumors rarely are seen on x-rays; when seen, carcinoid tumors are more common. 32 |

| Subcutaneous(FIG. 32-22) | Extensive calcification resulting from scleroderma, dermatomyositis, and subcutaneous fat necrosis; this calcification can project over the abdomen and seem to be intraabdominal. 26 |

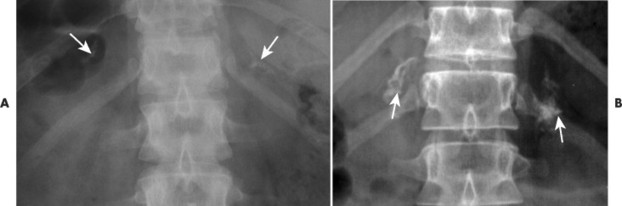

| Lymph node(FIG. 32-23; SEE ALSOFIG. 32-28, A) | Mesenteric lymph nodes: most common abdominal nodes to calcify; 57 they are one of the more common types of abdominal calcifications seen; healed tuberculosis is sometimes the cause of these calcifications, with exposure usually occurring several decades previously. 57 |

| Peritoneal | Psammomatous calcifications appearing within ovarian cystadenocarcinoma and its peritoneal implants; they may be widespread. 63 |

| Scars(FIG. 32-24) | Occasionally peculiar-shaped calcifications, often located in the abdominal wall. |

|

| FIG. 32-21 Uterine leiomyoma. Mass calcification associated with uterine leiomyoma is very common. Location and pattern of calcification are helpful in determining the diagnosis. |

There are numerous sources of free air in the peritoneal cavity. In some patients this is a benign, inconsequential finding, but in others it indicates such grave conditions as perforation of a hollow viscus.

AB2a. Most Common Causes of Pneumoperitoneum

| DISEASE | COMMENTS |

|---|---|

| Recent laparotomy | Usually present for 3 to 7 days after laparotomy, occasionally longer; 55 the volume of air decreases daily; faster resorption is seen in young adults. 25 |

| Trauma | Can be secondary to diagnostic studies such as peritoneoscopy and culdoscopy or from perforation during double-contrast barium enema or with colonoscopy; pneumoperitoneum may occur after severe external trauma. |

| Spontaneous | Most common cause: perforation of gastric or duodenal ulcer; rarely, air enters peritoneum via uterus and fallopian tubes (from puberty on). |

AB2b. Plain Film Technique for Detection of Pneumoperitoneum

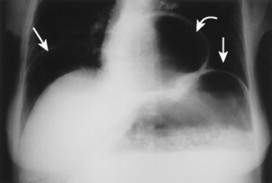

A complete series to detect free air includes erect and decubitus abdomen and upright posteroanterior chest views. 42 This approach occasionally requires up to 30 minutes to allow air to migrate between views, although larger amounts migrate faster and smaller amounts usually do not need more than a few minutes to migrate.

| PROJECTION | COMMENTS |

|---|---|

| Left lateral decubitus | Should be performed first; 43 patient is placed in left lateral decubitus position for 10 or 20 minutes (if the condition affecting the patient permits); lower right lung field is included in the film; chest technique is used. 42 |

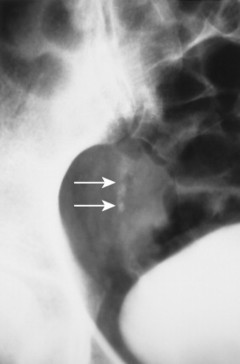

| Upright view (FIG. 32-25) | Patient placed in sitting or standing position for a few minutes, 5 to 10 minutes if possible; film is centered at thoracolumbar junction area. 42 |

| Supine film | May be only film taken in acutely ill patients; however, smaller amounts of air usually are not seen; one must be familiar with these subtle signs of pneumoperitoneum on the supine film if the condition is to be recognized. 42 |