VASCULAR DISORDERS

Specific Selected Conditions

INFECTIOUS AND INFLAMMATORY PROCESSES OF THE CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM

Specific Selected Conditions

Spinal Infections

NONINFECTIOUS INFLAMMATORY CONDITIONS

Multiple Sclerosis

Sarcoidosis

Tumors of the Central Nervous System

PRIMARY TUMORS

Glioma

Meningioma

Neurofibroma or Schwannoma

Pituitary Adenomas

Medulloblastoma

Lymphoma

Craniopharyngioma

Teratoma

SECONDARY TUMORS

Metastasis

MISCELLANEOUS SELECTED CONDITIONS

Arnold-Chiari Malformation

Empty Sella Syndrome

Syringohydromyelia

Tarlov or Arachnoid Cyst

Trauma

BACKGROUND

Trauma to the head accounts for more deaths and disability in the United States than any other neurologic disorder among individuals under the age of 50. 185,304 More than 50,000 people die each year because of brain trauma, about one third of all injury deaths, with approximately 11,000 new cases of spinal cord injury reported during the same time. 56,59,151,185 Motor vehicle accidents cause approximately half of the traumatic brain injuries in the United States, with falls and firearms responsible for most of the remaining cases. 151,304 Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a cause of long-term disability that annually affects an estimated 70,000 to 90,000 people. 56 Public health efforts to prevent the occurrence and mitigate the consequences of TBI have received increased attention in recent years because of the serious outcome and large number of people affected. Alcohol is often a precipitating factor in these injuries. 59,67 The clinical assessment of the posttraumatic patient is discussed with emphasis on appropriate diagnostic imaging.

IMAGING FINDINGS

Spinal trauma.

It is appropriate to initially evaluate the posttraumatic patient with plain films. Radiographic examination of the cervical region should include anteroposterior (AP) open mouth, AP lower cervical, neutral lateral cervical, and possibly oblique cervical and flexion-extension projections, depending on patient presentation. If the C7 vertebral body and posterior arch structures are not well demonstrated in the routine examination, overexposed lateral cervicothoracic spot or swim lateral cervicothoracic spot radiographs are recommended. Visualization of the C7 level is extremely important because posterior arch and vertebral body fractures often are overlooked because of summation of shoulder structures. Passive flexion lateral cervical and extension lateral cervical radiographs are particularly helpful for evaluation of intersegmental stability.

Radiographic or clinical assessment may provide justification for more specialized imaging. If fracture is suspected, a three-view cervical series with computed tomography (CT) is prudent. CT is superior to oblique projections and other plain film views to demonstrate the osseous anatomy of the vertebral arch. Axial imaging often allows visualization of fractures that are not discernible on routine radiography. In addition, CT examination may render a more detailed understanding of the extent of fracture deformity previously detected in a routine radiographic examination. CT permits visualization of the central canal, including retropulsed fracture fragments and stenosis caused by misalignment. Occasionally a nuclear bone scan or single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) might be advantageous in those patients who exhibit clinical findings suggestive of an occult posterior arch fracture. These are frequently not well demonstrated with plain films or CT because of the orientation of the fracture. Fractures in a horizontal plane may not be visible in axial imaging, although reformatting in the coronal, oblique, and sagittal planes may be beneficial. Reformatted CT images also may be useful in determining a treatment plan for complex fractures. 190,199

If sufficient clinical indications exist, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan may be necessary to demonstrate the ligaments, intervertebral discs, and soft tissues within the spinal canal or intervertebral foramina. MRI is the preferred examination in patients with spinal cord edema, hematoma, or transection. Space-occupying lesions that may cause mass effect on the spinal cord or nerve roots are well perceived. Late effects of trauma to the spinal cord are best examined by MRI, including gliosis, myelomalacia, and syringomyelia. 192

Examination of the thoracic and lumbar regions should proceed in the same manner as in the cervical spine with initial plain film radiography, including at least AP and lateral projections. One should demonstrate the thoracolumbar junction, because this transitional region is a common area for fracture. Lumbar oblique projections may be added, particularly for evaluation of the posterior arch anatomy. Tilting up lumbosacral spot (L5-S1 AP or Hibb’s projection) and lateral lumbosacral spot radiography may help to better visualize the lumbosacral junction. Special imaging should be performed if indicated by clinical or plain radiographic findings. Lumbar or thoracic trauma may result in different neurologic findings than in the cervical region. For instance, the cauda equina and conus medullaris syndromes are indigenous to the lumbar region, whereas quadriplegia is caused by a cervical spine injury. These patients should be imaged appropriately according to their individual clinical findings. 134,275

Brain and skull trauma.

Patients with head trauma constitute a large percentage of cases referred for neuroimaging. Imaging of hyperacute trauma (<24 hours) to the skull and brain should begin with MRI or CT, particularly in a patient with neurologic deficit, because the diagnostic yield of plain film radiography does not warrant its use. In the first 24 hours after trauma, CT is the imaging modality of choice rather than MRI. Emergency equipment is more easily used with CT rather than MRI because of the incompatibility of equipment with a strong magnetic field. However, recent advances have resulted in the commercial introduction of more MRI–compatible patient stabilization equipment. 171,229,304

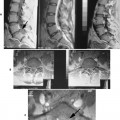

Attenuation of blood in CT scans is dependent on its constituent components because serum is less dense than protein and red blood cells. Therefore serum displays less attenuation than brain tissue, whereas the other products of hemorrhage and hematoma exhibit greater attenuation than the brain. Assessment of fractures and penetrating injuries is easily accomplished with CT in most cases and is fast, reliable, and easily accessible in most communities (Fig. 33-1, A to C). CT is compatible with patient stabilization devices and monitoring equipment. 53 Posttraumatic CT protocol should include 5- to 10-mm thick contiguous axial images from the skull base to the vertex with bone, brain, and subdural windows or level settings. Limitations resulting from beam hardening artifact should be taken into consideration, particularly in the frontal, parietal, occipital, and cerebellar regions. In those patients who require assessment of vascular injury, magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), duplex or transcranial ultrasound, CT with contrast, or conventional catheter angiography is used. 43,93,171,276

|

| FIG. 33-1 Trauma. Closed head injury in a 48-year-old man as the result of a high-speed motor vehicle collision. A, Axial noncontrast soft-tissue window computed tomography image shows an oblique fracture line through the right frontal sinus (large arrow), bilateral frontal lobe hemorrhagic contusions with associated edema (curved arrow), and blunting of the anterior horn of the left lateral ventricle (angled arrow). B, Axial bone window images demonstrate a comminuted nasal fracture and extensive fractures of both maxillary sinuses with air-fluid levels (arrows). C, Axial bone window image of the frontal bone illustrates a displaced fracture through the right frontal sinus (large arrow). This introduces free air into the cranial vault (small arrows) and puts the patient at risk for meningeal infection. |

MRI is superior to CT in the demonstration of blood products in the acute, subacute, and chronic posttraumatic patient, as well as nonhemorrhagic lesions such as diffuse axonal injury, cortical contusions, white matter shear injury, and brainstem lesions. Within the past 10 years, recognition of a deoxyhemoglobin rim in hyperacute injuries has made MRI a reasonable alternative to CT. 22 In addition, MRI is better at visualization of hemorrhages within the brain parenchyma and subcortical gray matter. 93,267 MRI provides direct multiplanar acquisitions in the axial, sagittal, or coronal planes and permits excellent soft-tissue contrast. In imaging hemorrhage or hematoma in the brain, the MRI signal is dependent not only on the length of time that the blood has been present, but also on the strength of the magnet. Familiarity with the MRI system is essential in determining the signal characteristics to be expected in the various time stages after trauma. 23,216,275

Blood products are predominantly oxyhemoglobin with a deoxyhemoglobin rim in the hyperacute stage after trauma (<24 hours). Deoxyhemoglobin is more prevalent in the acute stage (24 to 72 hours), whereas methemoglobin predominates in the subacute/late phase (72 hours to 2 weeks). Methemoglobin remains in the central portion of the lesion, whereas hemosiderin surrounds the periphery after 2 weeks. Eventually hemosiderin deposition dominates the blood products in the late chronic stage with low signal characteristics on both T1- and T2-weighted images (Table 33-1). *

| Time following trauma | Hemoglobinhemosiderin | Magnetic resonance imaging signal characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Hyperacute (<24 hours) | Oxyhemoglobin-deoxyhemoglobin rim | Intermediate T1, high T2, low T2 rim |

| Acute (24–72 hours) | Deoxyhemoglobin | Intermediate T1, low T2 |

| Subacute early (3–7 days) | Early, intracellular methemoglobin | High T1, low T2 |

| Subacute late (1–2 weeks) | Later, extracellular methemoglobin | High T1, high T2 |

| Chronic early (>2 weeks) | Extracellular methemoglobin with a hemosiderin rim | High central signal in both T1 and T2, low signal rim |

| Chronic late (>2 months) | Hemosiderin predominates late | Low T1, low T2 |

CLINICAL COMMENTS

The most common head injuries result from blunt or nonpenetrating trauma. These injuries frequently induce a temporary or longer loss of consciousness, and the brain may suffer gross damage in spite of the absence of skull fracture or penetrating injury. Skull fractures may serve to indicate the presence of significant trauma; however, the presence or absence of a skull fracture cannot be used to predict the presence or severity of intracranial injury.

Trauma to the head and spine often requires emergency evaluation and treatment performed by an emergency team at the site of injury. It is essential that the injury not be compounded by excessive movement immediately after trauma. The cervical spine must be stabilized before transport. If time allows, a cursory physical and neurologic assessment of the patient is recommended. Evaluating the ABCs (airway, breathing, and circulation) is suggested, and the Glasgow coma scale (GCS) is used to assess posttraumatic brain injury. The outcome of the GCS and severity and type of trauma are good predictors of mortality. 284 Spinal cord injury may mask injuries below the level of the trauma, particularly in the abdominal region. 59 Before the arrival of emergency medical transportation, a physician may administer cardiopulmonary resucitation (CPR), treatment for shock, or other life-sustaining procedures, always avoiding further spinal cord injury. State Good Samaritan laws should be understood before initiating care. Even if a Good Samaritan law is in place, some jurisdictions consider it “gross negligence” to provide care at a level beyond which a person is trained.

• In spinal trauma, radiographs should be accomplished first with good visualization of C7, the thoracolumbar junction, and the lumbosacral junction.

• Radiography or clinical findings may suggest the need for special imaging.

• Computed tomography (CT) is particularly useful in evaluation of possible posterior arch fractures.

• Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is helpful in assessing the soft tissues, ligaments, discs, spinal canal, and intervertebral foramina.

• With skull trauma, CT or MRI should be done first; plain film generally is inadequate for patient evaluation.

Specific Selected Injuries

Acute Cortical Contusion

BACKGROUND

By design the skull is a rigid shell that protects the brain from direct injury. The inner table of the vault has roughened edges, ridges and bony prominences along the floor of the anterior fossa, sphenoid wings, and petrous pyramids that can contuse the brain surface during the compressive force of a traumatic event.

Cortical contusions or bruises may occur by direct trauma (coup) or by the brain rebounding and striking the skull (contrecoup) because of acceleration and deceleration. 201,259 A vascular injury must be present for bruising to occur. Parenchymal lesions are found on the surface of the brain in the form of microhemorrhage with edema. Cortical contusions typically are multiple and measure approximately 2 to 4 cm in diameter. Thirty to fifty percent of these lesions are hemorrhagic. 56 Cellular disruption is associated with the release of vasoactive substances. The resulting vascular permeability to serum proteins facilitates a progressive increase of interstitial fluid. Over a short period of time, blood and edematous fluid advance within the white matter and into the subdural and subarachnoid spaces, producing a mass effect on adjacent anatomic structures and positive neurologic findings. Approximately 50% to 75% of cortical contusions involve the frontal and temporal lobes, especially the lateral aspects of both lobes and inferior surface of the frontal lobe. 56 The falx, tentorium, and cranial fossae are especially vulnerable areas. 201,218 Gliding and shearing injuries often are bilateral with tearing of the parasagittal venous structures. 218,249

IMAGING FINDINGS

CT usually is employed for initial evaluation of hyperacute cortical contusion because it is fast, reliable, and readily available. Recognition of hyperacute cortical injury is dependent on increased attenuation in the region of the contusion. However, CT has a tendency to underestimate the size of these lesions soon after injury because of isoattenuation with edema and surrounding brain tissue. Repeat scanning often allows complete visualization of original foci and recognition of other sites of involvement. CT also produces beam-hardening artifacts that hamper imaging of more peripheral parenchymal cortical tissue adjacent to the skull. 321

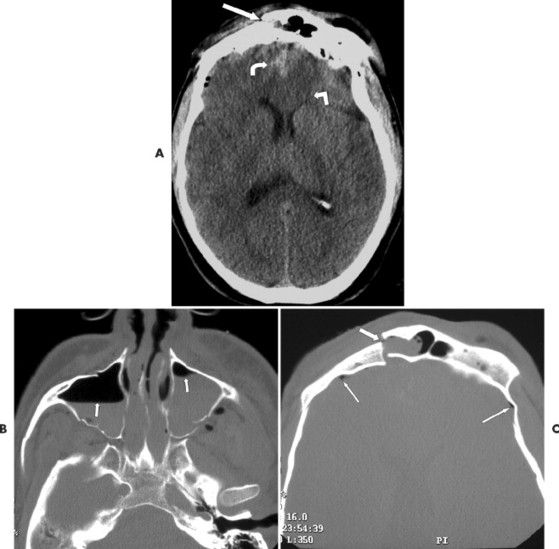

MRI typically demonstrates contusion in the hyperacute stage, particularly if gradient echo and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) protocols are used. 201,250,251 MRI is particularly sensitive to surrounding edema and peripheral cortical foci that may be overlooked on CT. However, many facilities are not equipped with MRI–compatible emergency equipment. In addition, claustrophobia, sedation to reduce motion, and large body habitus must be taken into consideration if MRI is performed instead of CT. MRI is ideal for evaluation of cortical contusions in later stages when emergency equipment is no longer needed. 23,201 The signal intensity of cortical contusion is similar to other blood products produced by trauma (see Table 33-1). Cortical contusion often is associated with other intracranial lesions, such as subdural hematoma (Fig. 33-2, A to C). SPECT scans are being used occasionally for diagnosis of cortical contusion. SPECT scanning also has been used in a monitoring role to follow patients with traumatic brain injury. 155

|

| FIG. 33-2 Cortical contusion. A, Right frontal and left parietal cortical contusions are apparent (long arrow, curved arrow) in the gradient recall axial acquisition with an area of cortical edema in the right posterior parietal region (short arrow). B, Peripheral enhancement is visualized in the right frontal contusion in the postcontrast T1-weighted axial image (arrow). C, The T2-weighted axial image demonstrates heterogenous increase in signal at the right frontal cortical contusion with increased signal in areas of edema adjacent to the posterior parietal region and posterior to the posterior horn of the left lateral ventricle. A subdural hematoma is discernible incidentally anteriorly on the left side (arrows). (Courtesy Bryan K. Hosler, Cincinnati, OH.) |

CLINICAL COMMENTS

Focal neurologic deficits are late-appearing clinical findings. Confusion, focal cerebral dysfunction, seizures, and personality changes are seen more frequently early in cases of cortical contusion.

• Trauma may be coup or contrecoup and result in bleeding into the brain.

• Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be performed in the hyperacute stage depending on facilities.

• MRI is better than CT after 24 hours.

Acute Epidural Hematoma

BACKGROUND

Epidural hematomas may occur within the spine or skull when blood accumulates between the dura and surrounding bone. If the arteries are torn because of a severe shear trauma that separates the dura from the bone, blood may accumulate rapidly in the potential space created by this injury. If there is venous compromise, a slower, more chronic pattern may result. The middle meningeal artery is involved most often after skull trauma, although the ethmoidal artery or sinuses (superior sagittal, transverse, or sigmoidal) may be traumatized depending on the exact site of trauma. A small percentage of epidural hematomas are bilateral (<10%), whereas the great majority exhibit skull fractures (>90%). The calvarial periosteum (dura layer) is bound down at the suture margins, creating an anatomic boundary to hemorrhage. 169,218

There are numerous causes for spinal epidural bleeding other than high-impact trauma. Spinal epidural hematoma often occurs in conjunction with disc herniation because of involvement of the epidural venous plexus and may be responsible for neural effacement. MRI signal characteristics of disc versus blood must be thoroughly explored, because a space-occupying lesion caused by blood resolves much more quickly than disc debris. This characteristic may clarify the rapid resolution of “sequestered” disc herniations that are in reality spinal epidural hematomas. 105In addition, thrombolysis, anticoagulation therapy, lumbar puncture, spinal epidural injections, hypertension, and blood dyscrasias may result in spinal epidural hematoma with compromise of neural structures caused by mass effect. These conditions produce symptoms similar to disc herniation, including back pain, numbness or paresthesias, lower extremity weakness, and incontinence (both urinary and fecal). 169

IMAGING FINDINGS

Imaging of both intracranial and spinal epidural hematomas usually begins with CT, although MRI also is diagnostic in the stable patient or in facilities that are equipped with MRI–compatible emergency and stabilization equipment. MRI is particularly useful in evaluation of spinal epidural hematoma and its consequences with surrounding neural structures. In the brain, considerable midline shift, large hematoma volume, signs of active bleeding (mixed density clot on CT), and the presence of other associated lesions are suggestive of a poor prognosis after skull trauma. These imaging findings are correlated with clinical signs such as age, coma, papillary abnormalities, and GCS or motor score to help determine an outcome. 218,230,258,295 The hematoma typically is lentiform shaped and hyperdense on CT, although less dense areas occur in regions where there is serum or recent bleeding. The area of hematoma usually is homogeneously hyperdense 72 hours after cessation of bleeding. Signal characteristics in MRI scans are typical of other forms of hematoma (see Table 33-1).

CLINICAL COMMENTS

A transient loss of consciousness may occur with intervals of mental lucidity. Palsy of cranial nerve III may be present and is a sign of cerebral herniation. Somnolence, sleepiness, or unnatural drowsiness 24 to 96 hours after injury constitutes a medical emergency.

• Hematomas occur in the epidural space of the brain or spine.

• Computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging scans are used rather than plain film radiography.

• Imaging findings should be correlated with clinical signs.

Acute Subdural Hematoma

BACKGROUND

Subdural hematomas are caused more frequently by venous rather than arterial damage and are often self-limiting because of the slow bleeding process. However, if the hematoma is large, mass effect may take place, shifting cerebral structures and causing edema in the parenchyma of the brain, resulting in a poor clinical outcome. Subdural hematomas arise deep to the dura but external to the arachnoid membrane, and the untreated hematoma may become subacute or chronic. Acute subdural hematoma is more common in older age groups because the veins are less resilient and more easily damaged. Patients taking anticoagulants and alcoholic patients are also prone to acute subdural hematoma. 152,249,304,311

IMAGING FINDINGS

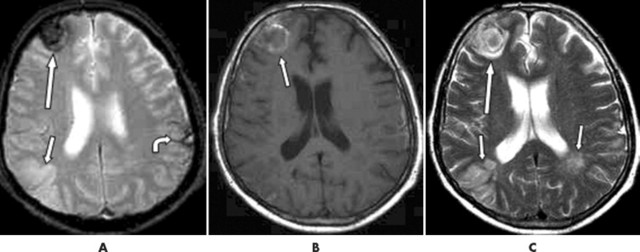

MRI is more accurate than CT in assessing the size of a subdural hematoma and its effect on surrounding parenchymal tissue (Fig. 33-3). 249 Nonetheless, CT frequently is the imaging modality used because of accessibility, rapid acquisition, and compatibility with emergency equipment. On CT scans, increased density is visualized along the inner table of the skull, most commonly in the parietal region. Small hematomas may be difficult to visualize, and adjustment of the window level or width between usual bone and soft-tissue windows may be necessary. Edema is not as easily perceived with CT as MRI. False-negative CT findings may occur as the result of a high-convexity lesion, beam-hardening artifact, or volume averaging with the high density of calvarium obscuring flat “en plaque” hematomas. Approximately 38% of small subdural hematomas are missed on CT. 56 Cerebral edema should be suspected and MRI accomplished if midline shift has occurred. 93,171,190,249,275 A blood-fluid level is appreciated occasionally.

|

| FIG. 33-3 Subdural hematoma. Large subdural hematoma (large arrow) present on the left side of the Gd-DTPA–enhanced T1-weighted coronal acquisition. Smaller subdural hematoma apparent on the right side (small arrows). (Courtesy Bryan K. Hosler, Cincinnati, OH.) |

• Acute subdural hematomas are usually caused by damage to the veins and are often slow to develop.

• Hematomas are more common in older patients and in those who are alcoholics or taking anticoagulants.

• Magnetic resonance imaging may be better for small bleeds adjacent to bone and for visualization of surrounding edema.

Acute Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

BACKGROUND

Extravasation of blood deep to the arachnoid and above the pia mater is defined as subarachnoid hematoma and most frequently is caused by trauma, although often this type of hematoma is caused by vascular compromise, particularly aneurysm and arteriovenous malformation. Laceration of the microvessels in the superficial portion of the subarachnoid space causes subarachnoid hemorrhage. Posttraumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage may be benign. However, a communicating hydrocephalus may develop because of obstruction of the arachnoid villi or a noncommunicating hydrocephalus because there is a blood barrier for cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flow through the third or fourth ventricle. Vasospasm and subsequent cerebral ischemia is another complication of traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage. 43,59,323 Clinical prognosis is dependent on the volume of blood in the subarachnoid space.

IMAGING FINDINGS

CT is an extremely sensitive test for subarachnoid hemorrhage, particularly in the first 12 hours, although 1 hour is necessary for enough clot retraction to take place for sufficient protein concentration to become hyperdense. Within the past 10 years, it has become possible to demonstrate parenchymal and subarachnoid hemorrhage on MRI with confidence. Studies have shown that FLAIR MRI sequences allow visualization of acute subarachnoid hemorrhage better than CT or other MRI pulse sequences, particularly in the posterior fossa because of beam-hardening artifacts in CT. 22,46,102,212,272 Recognition of the deoxyhemoglobin border surrounding areas of oxyhemoglobin in T2-weighted MRI acquisitions also has made it possible to image blood products in the hyperacute patient. 22 Thin slice CT must be performed to recognize small bleeds; blood may be isodense with brain tissue if the hematocrit levels are below 30. 243,265 An extremely small percentage of patients have false-negative CT or MRI scans. Lumbar puncture is indicated in those patients who exhibit symptoms of subarachnoid hemorrhage who have a negative CT or MRI examination. 296 It must be remembered that lumbar punctures often are falsely negative in the first 12 hours after injury. 71,243,265

• Posttraumatic subarachnoid hematoma may be benign but may be associated with hydrocephalus- or vasospasm-induced ischemia.

• Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) scans are used and are extremely sensitive.

• If clinical findings suggest a subarachnoid hemorrhage, a lumbar puncture should be performed, even though MRI and CT scans are negative.

Vascular Injury

BACKGROUND

Blunt trauma to the internal carotid, middle cerebral, and anterior cerebral arteries is more commonly the cause of brain ischemia than injuries to other arteries. The external carotid, vertebral, and subclavian arteries are not common sites of injury; posttraumatic brain ischemia and penetrating injuries cause most damage to these arteries. Fractures at the base of the skull and mandible frequently are encountered with traumatic carotid injuries. 44,67,92,323

With relatively minor trauma, disruption of the vascular intima leads to a hemodynamic situation ideal for platelet deposition and thrombus formation. The thrombus eventually may occlude the entire vascular lumen, resulting in cerebral ischemia and infarction. In addition, traumatic disturbance of atherosclerotic plaque may give rise to an embolus.

Higher-force trauma may lead to more complete tearing of the intima, resulting in dissecting aneurysm as pulsatile high-pressure blood forces its way between the intima and media. 88,323 Dissecting extracranial aneurysms are most commonly found in the cervical portion of the internal carotid as it enters the skull, whereas intracranial aneurysms most frequently occur at branches of the middle cerebral artery. Turbulence may cause the aneurysm to enlarge with thrombus formation and possible distal embolization. 88

IMAGING FINDINGS

Vascular injuries may be examined by MRA, catheter angiography, duplex ultrasound, transcranial Doppler ultrasound, and SPECT. 155,234,267,274,278 MRA is noninvasive and presents a viable alternative to conventional catheter angiography. Reconstruction of thin slice two- or three-dimensional time-of-flight axial images using “flow phenomena” allows visualization of the vessel with an angiographic appearance. Phase contrast studies provide information about volume and velocity of blood flow. The key finding in MRA of an intimal tear with dissection is demonstration of the intimal flap that separates the true from the false lumen of the vessel. The lumen may be narrowed with increased signal within the entirety of the lumen or in the periluminal region. * Catheter angiography reveals an irregular narrowing of the vessel or the classic “string sign,” and the intimal flap also may be visualized. Total occlusion from hematoma or thrombus causes interruption of signal on MRA and flow void on angiography. 90,321 Duplex and transcranial ultrasound rapidly is becoming more popular because it is fast, inexpensive, sensitive, and noninvasive. 274,278

• Trauma to the head or neck may cause arterial thrombus or dissecting aneurysm.

• Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) is noninvasive, and new protocols have made MRA a feasible alternative to catheter angiography.

• Advances in duplex and transcranial diagnostic ultrasound have made these modalities an alternative to catheter angiography.

Traumatic Pseudoaneurysms

BACKGROUND

A pseudoaneurysm or “false” aneurysm is created by rupture of all three arterial walls (intima, media, and adventitia), although egress of blood flow from the vessel is contained initially by surrounding fibrous tissue in the adventitia. These lesions may extravasate blood into the surrounding tissues, which may gradually or abruptly increase in size, resulting in pressure on surrounding structures. Pseudoaneurysm of the vertebral artery is usually observed at the C1-2 level. Rupture or distal embolization may take place. 276 Catheterization (particularly in patients undergoing anticoagulant therapy or antiplatelet medication), rotational trauma, and infection may be causative factors for pseudoaneurysm. 6,116,136 Treatment includes duplex-guided compression (peripheral extracranial vessels), thrombin injection, and surgical repair. 37

IMAGING FINDINGS

Duplex and transcranial Doppler ultrasonography are becoming increasingly more reliable in early diagnosis of traumatic pseudoaneurysms. Various bone windows are being used for transcranial Doppler. For example, the temporal bone is thin and can be used as a window to reveal segments of the middle cerebral, internal carotid, anterior cerebral, and anterior communicating arteries. The ophthalmic artery is visible through the orbital window and the basilar artery by the suboccipital approach. 143,234,239

The ability of transcranial Doppler ultrasound and phase contrast MRI to measure volume and velocity of blood flow is particularly useful. However, patients undergoing surgery should have MRA or catheter angiography. MRA is a practical alternative to catheter angiography when patients are allergic to contrast dye, have renal insufficiency, or desire a noninvasive examination. 275 Accuracy for carotid stenosis is virtually assured if MRA and ultrasound findings correlate. Nonetheless, if there is no correlation between MRA and ultrasound, conventional angiography should be done, if possible. 77,78

• Traumatic pseudoaneurysm takes place when there is a rupture of the vascular wall because of injury.

• Diagnostic ultrasound and phase contrast magnetic resonance imaging allow measurement of volume and velocity of blood flow.

• Diagnostic ultrasound, magnetic resonance angiography, and conventional catheter angiography should be used in conjunction with one another to provide an accurate diagnosis.

Vascular Disorders

Specific Selected Conditions

Stroke

BACKGROUND

Disruption of the local blood supply to the brain produces ischemia and eventual infarction of brain parenchyma. Large infarctions may be associated with marked cerebral edema resulting in gross shifting of midline structures, herniation, and death caused by brainstem compression. Stroke is the third most common cause of death and the primary cause of severe disability in the United States. It is the second leading cause of death in patients over 75 years of age. 56 Stroke may result from ischemia or hemorrhage. The majority (80%) of cases result from ischemia because of extracranial embolus or intracranial thrombosis. Hemorrhagic strokes may be secondary to brain neoplasia, arteriovenous malformation, subarachnoid cyst, and anticoagulant therapy. A sudden loss of circulation to the brain results in infarction and loss of neurologic function. The site of occlusion and size of infarction control the subsequent clinical outcome. Symptoms include nausea, vomiting, headache, vertigo, aphasia, visual disturbances, diplopia, and neurologic deficit such as sudden-onset paresis, hypesthesia, or ataxia. Risk factors include high blood cholesterol, advanced age, smoking, hypertension, atherosclerosis, and cardiac disease. 7,15

IMAGING FINDINGS

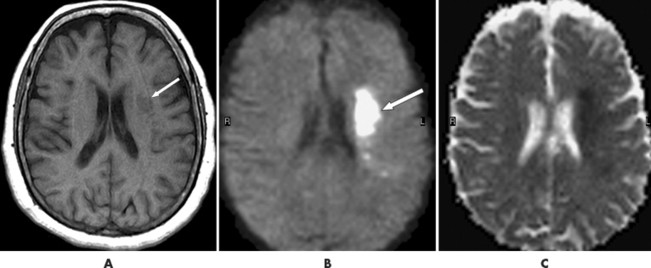

Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) make clinically relevant information available about presence, age, and location of lesions minutes after onset of ischemia that is not appreciated on conventional MRI examinations or CT (Fig. 33-4, A and B). 250,251,317 DWI relies on the differences of tissue water diffusion properties for visualization of lesional tissue. Increase in signal is directly proportional to increased water diffusion on DWI examinations. Both conventional MRI and DWI have been shown to be considerably more accurate than CT in characterization and demonstration of acute cerebral infarct. 156,294,317 Functional MRI (fMRI) permits early evaluation of stroke. The patient is instructed to perform a task during an fMRI examination. The metabolism in the brain accelerates in the area used to accomplish this task, altering MRI signal. fMRI is particularly useful in mapping brain tissue for surgery or radiation therapy.

|

| FIG. 33-4 Acute infarction. Left-sided brain acute infarction. A, Area of hypointensity (arrow) detected in the basal ganglia adjacent to the left lateral ventricle in the postcontrast T1-weighted axial image. Lesion does not enhance with gadolinium-diethylene-triamine-pentaacetic acid (Gd-DTPA) administration. B, Diffusion-weighted imaging demonstrates increased signal (arrow). C, Decreased signal in the apparent diffusion coefficient image typical of an acute infarction. |

Another relatively new technology, diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), uses gradients not only in the x, y, and z planes, but also in six noncollinear directions simultaneously; therefore both the direction and magnitude of water diffusion in space can be measured independently of patient or white matter fiber orientation. In DTI, an echo planar technique is used that allows determination of the structural integrity of white matter fibers by a method called anisotropy. Anisotropy is the diffusion of water or a metabolite in a specific direction. DTI uses the fact that myelin is a barrier to diffusion of water molecules to allow assessment of the integrity of white matter fibers on a microscopic scale. *

CLINICAL COMMENTS

Death during hospitalization occurs in approximately 25% of stroke patients. Patients with an alteration in consciousness, gaze preference, and dense hemiplegia have a 40% mortality rate. Survival with varying degrees of neurologic deficit occurs in 75% of patients. Forty percent of stroke patients can expect a good functional recovery. Indications for cerebrovascular testing include transient ischemic attack (TIA), progressive carotid arterial disease with 95% to 98% stenosis, and the presence of cardiogenic cerebral emboli. 56

• Stroke is caused by interruption of normal blood flow to brain parenchyma.

• Stroke may lead to severe neurologic deficit or death.

• Diffusion-weighted and diffusion tensor magnetic resonance imaging allow early evaluation of stroke patients.

• Transcranial Doppler diagnostic ultrasound may be useful in certain types of stroke.

Nontraumatic Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

BACKGROUND

Approximately one third of all patients diagnosed with subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) have a demonstrable neurologic deficit. Forty to fifty percent of patients with SAH die within the first month. Saccular aneurysms often rupture spontaneously and account for two thirds of all nontraumatic SAH, resulting in more than 18,000 deaths per year. The remaining cases of SAH are caused by arteriovenous malformation, mycotic aneurysm, cortical thrombosis, angioma, and various other invasive neoplasia. Discrete and episodic bleeding from the wall of a saccular aneurysm, known as a “warning leak,” may precede complete rupture. 96,128,209 Severe headache, often described by the patient as “the worst headache ever,” is a common complaint with SAH. These headaches typically are new to the patient with abrupt onset. Meningeal irritation caused by the hemorrhage is likely to produce nuchal rigidity or other signs of meningeal irritation (Brudzinski’s or Kernig’s sign). Other patient complaints include nausea, vomiting, neck pain, seizure, cranial neuropathy, visual disturbances, paresis, loss of consciousness, and coma. A high percentage of SAH patients undergo complications that include rebleeding and vasospasm. Eighty-five percent of all saccular intracranial aneurysms are found in the anterior cerebral circulation and occur at arterial junctions and branches. *

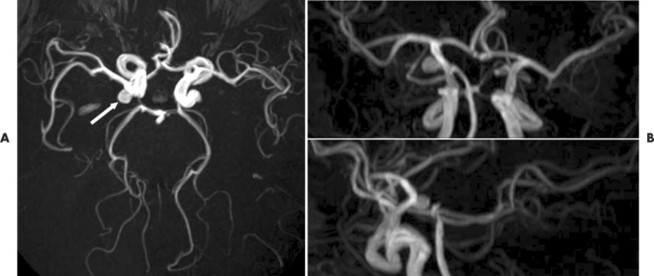

IMAGING FINDINGS

CT is sensitive for the first 24 hours after a SAH. The longer CT is delayed, the less sensitive the test becomes. In addition, it is necessary that the hemoglobin count exceed 10 g/dl or blood will be isodense to the surrounding brain tissue on CT. The bleeding event requires at least 1 hour for clot and protein concentration to be sufficiently dense to be visible on CT scans. 243,265 Catheter angiography is used to localize aneurysms and define their shape before surgery. MRA is sensitive for aneurysms exceeding 3 mm in diameter; this size is constantly decreasing as MRA becomes more sensitive (Fig. 33-5, A and B). MRI also is sensitive in SAH in both the hyperacute and subsequent stages, particularly if FLAIR, DWI, and DTI sequences are employed. † Lumbar puncture is positive in most cases when there is a “warning leak” or SAH, although blood is not found in the CSF until 12 hours after the onset of bleeding. Care also must be taken to exclude traumatic lumbar puncture as a cause for blood in the CSF. Lumbar puncture should not be performed if there are imaging findings suggestive of increased intracranial pressure or mass effect because of the possibility of brainstem herniation. 48,71,243,265

|

| FIG. 33-5 Saccular aneurysm. A and B, Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) of the circle of Willis illustrates a saccular aneurysm on the right side (arrow). MRA is noninvasive and may be accomplished without contrast. (Courtesy Bryan K. Hosler, Cincinnati, OH.) |

• Most nontraumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage is related to aneurysmal rupture.

• Severe headache is usually present.

• Magnetic resonance angiography, magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography, and lumbar puncture are diagnostic methods useful in the evaluation of subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Vascular Malformation

BACKGROUND

Arteriovenous malformation (AVM), cavernous hemangioma, venous angioma, and capillary telangiectasia are common forms of vascular malformation. The latter two are of little clinical significance because they are relatively benign and rarely symptomatic. AVMs may be found in the brain or spine, but are much more common in the brain. The tangled masses of arteries and veins that make up an AVM communicate with one another without normal capillary function. Neural parenchyma lies between the vessels in an intracranial AVM. Blood is shunted directly between the arterial and venous systems in the AVM, resulting in an increased venous pressure that helps to facilitate hemorrhage. Although the great majority of patients with AVMs are asymptomatic, approximately 12% of patients with AVMs present with severe headaches, seizures, and progressive neurologic deficit. Aneurysms are present in more than 5% of individuals with AVM, usually in the arteries feeding the AVM. AVM should be considered in the differential diagnosis if there is a high clinical suspicion of intracranial hemorrhage. This is particularly important in young patients. Spinal AVM may present with weakness, numbness, or motor dysfunction in the extremities that may lead to paresis. Bladder and bowel dysfunction are also a consequence of spinal AVM. Treatment is surgical. 97,232,270

Cavernous hemangiomas are also known as cavernous angiomas and cavernomas. They were previously considered angiographically occult or cryptic vascular malformations because they were not readily discernible on catheter angiography. Cavernous hemangiomas are endothelial-lined sinusoidal spaces and are slow flow lesions rather than rapid shunts. Brain tissue is not interposed between the abnormal vessels as it is in the AVM. Less than 25% of cavernomas are asymptomatic. They often bleed and may cause seizures or neurologic deficit. Hemangiomas may be seen in the spinal cord but are uncommon. The treatment of intracerebral and spinal cord hemangiomas is surgical or stereotactic radiosurgery. 97,189,232

IMAGING FINDINGS

Often CT is used early in the diagnosis of AVM. However, nonhemorrhagic AVMs often are isodense to surrounding brain matter and overlooked on CT. Only 20% to 30% of AVMs calcify and are visible on CT. The high sensitivity of MRI to flow void makes MRI the most accurate modality for imaging of AVM. A diagnosis of AVM is established by the demonstration of multiple tortuous areas of flow void on MRI. Hemosiderin deposition secondary to hemorrhage produces a characteristic low signal, particularly on gradient echo acquisitions. In addition, high signal areas on T2-weighted images are suggestive of ischemia. Multiple serpiginous, irregular tubular structures are the hallmark of AVM in the spinal cord. Supplying arteries, lesional matrix, and venous drainage are discernible on digital subtraction catheter angiography, as well as those small aneurysms that may not be visible on MRA. Angiography usually is performed before surgery. 97,113,232

CT is fast and widely available. For these reasons CT is useful for early diagnostic workup of cavernous hemangiomas in emergent situations. However, MRI and MRA should be considered the imaging modalities of choice because they provide considerably more information about anatomy and pathophysiology than CT. Cavernous hemangiomas are not visible on conventional angiography and CT may not demonstrate all lesions. Edema is identified easily on MRI with high signal intensity on T2-weighted acquisitions. Repeated bleeds cause deposition of hemosiderin that produces a characteristic low signal ring appearance on MRI. Gradient echo MRI sequences are particularly well suited for the discovery and evaluation of small hemangiomas due to the sensitivity of gradient echo imaging to magnetic susceptibility artifact produced by hemosiderin. 24,113

• Arteriovenous malformations and cavernous hemangiomas are the most clinically important of the vascular malformations.

• Magnetic resonance imaging and magnetic resonance angiography are highly sensitive for vascular malformation and should be used if an emergent situation allows.

• Digital subtraction angiography is useful in visualization of small aneurysms, feeding arteries, arteriovenous malformation matrix, and draining veins in arteriovenous malformations and is usually performed before surgery.

• Cavernous hemangiomas are not demonstrated on digital subtraction angiography.

BACKGROUND

The brain, spinal cord, and their associated membranes comprise the central nervous system (CNS). Life-threatening infections may ensue if bacteria, viruses, fungi, protozoa, or parasites enter the CNS. The meninges (meningitis), brain (encephalitis, abscess), epidural region (epidural abscess), and spine (discitis, epidural abscess) are common locations for infection. Brain infections most commonly arise from infections at contiguous sites. The ear, mastoid processes, mouth, and sinuses are frequent primary sites. CNS infections also may appear because of hematogenous spread from remote extracranial sites of infection or through direct penetrating injury. 279,286 Spinal infections are the result of hematogenous spread, penetrating injury, or iatrogenic causes, including injections or surgery. However, more than 25% of patients with spinal infections display no perceivable primary infection. 63,194,225

Neck pain and stiffness, fever, vomiting, seizures, sensitivity to light, headache, weakness, and neurologic deficit are common symptoms. Signs of meningeal irritation include spinal and nuchal rigidity, Kernig’s sign, and Brudzinski’s sign, although these signs are not reliable indicators of infection. Numerous variable pathogens are responsible for CNS infection. Unusual pathogens and other concurrent infections should be considered in immunocompromised patients. Aggressive early treatment of CNS infections with oral or intravenous antibiotics is crucial. However, surgical intervention is necessary in some cases. 38 Antibiotic-resistant organisms have made treatment difficult or impossible in many instances. 194,225

Specific Selected Conditions

Abscess

BACKGROUND

Brain abscesses are not common but may cause severe symptoms, depending on the location and size of the abscess and the presence of surrounding inflammation. The location of the abscess may suggest its etiology. For example, those abscesses stemming from hematogenous dissemination may be multiple and vascular in distribution, whereas those resulting from sinusitis tend to be singular and located in the frontal lobe. CNS abscess is characterized initially by the presence of necrotic tissue surrounded by inflamed brain cells. Suppuration ensues, and mature abscesses are encapsulated pus-filled sacs. Less well-capsulated abscesses are prone to metastasis within the brain, producing multiple sites that usually are monomicrobial. Mass effect from the abscess and inflammation surrounding the abscess causes the brain to swell, permanently damaging adjacent brain tissue. Bacteria are the most common pathogens responsible for brain abscess, although fungi also may cause abscesses. 70,225,231,308

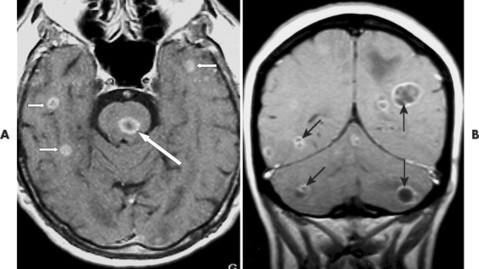

IMAGING FINDINGS

Fatalities have fallen by 90% since CT and MRI have been employed in the diagnosis of brain abscess. 26,186,308 MRI has proved to be more sensitive and specific in the diagnosis and follow-up of brain abscess than CT. 306 CT imaging findings are poor indicators of clinical progress, and CT scans tend to underestimate the number of lesions. Ring enhancement on contrast CT may be helpful in diagnosis, although a similar enhancement can be visualized in granulomas, tumors, and resolving hematomas. MRI with contrast (Gd-DTPA) allows better visualization in the initial stages of abscess formation and produces more complete imaging of the central necrotic tissue, surrounding rim, and edema with earlier detection of small satellite lesions than CT (Fig. 33-6, A and B). For this reason, an MRI scan should be performed even if the CT scan is normal when clinical evidence of infection exists. This is particularly important if the patient is immunosuppressed. 26,308 DWI appears to be a sensitive method in diagnosis of abscess and can help to differentiate necrotic-cystic tumors from abscesses. It should be noted that DWI is not specific for abscess. Treatment with steroids may impair the visualization of lesions on imaging by reducing mass effect and edema. Gallium, thallous chloride, and technetium SPECT imaging may allow discrimination between abscess and primary or metastatic brain neoplasias. 279,291

|

| FIG. 33-6 Brain abscess. A and B, Toxoplasmosis in a 51-year-old woman. Postcontrast T1-weighted coronal images illustrates peripheral enhancement of multiple abscesses in both cerebral hemispheres and the cerebellum (arrows). |

CLINICAL COMMENTS

Symptoms include headache, nausea, vomiting, fever, altered mentation, seizures, paresis, and focal neurologic deficit; none are pathognomonic of abscess. Clinical signs are those of increased intracranial pressure and are dependent on the site of the lesion. A cerebral lesion causes different symptoms than a cerebellar abscess. 26 Complete blood count and blood cultures may be suggestive of infection and the electroencephalogram, positive (although not specific) in those cases of focal neurologic deficit or seizure. A biopsy using stereotactic CT or MRI permits accurate needle placement. 168 The biopsy specimen then is cultured and an appropriate antibiotic regimen is established. A developing cerebral abscess is a medical emergency, and larger lesions (>2.5 cm) should be excised or stereotactically aspirated. 260 Many abscesses can be avoided with the early successful treatment of the primary site of infection. Lumbar puncture should not be employed because of the possibility of transtentorial herniation. CSF assay is within normal limits in an unruptured abscess. 26,70,98

• Although uncommon, abscess may have serious clinical consequences.

• Magnetic resonance imaging is the modality of choice for evaluation of abscess.

• Clinical signs and symptoms are suggestive of a central nervous system lesion but not specific for abscess.

Meningeal Infections

BACKGROUND

Infection of the inner two membranes (leptomeninges) covering the brain and spinal cord may result in meningitis. Spread can be hematogenous or secondary to sinus and ear infections. The blood–brain barrier effectively isolates the infection from the immune system. Untreated pyogenic (bacterial) meningitis may cause death or lifelong disability. Bacterial meningitis presents the most serious clinical implications, causing 2000 deaths in the United States annually. The most common bacteria responsible are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitides, Staphylococcus, and Haemophilus influenza type B bacteria (Hib). Cerebral infarcts, brain edema, paresis, seizures, hearing loss, blindness, and coma are common complications of pyogenic meningitis. In addition to bacteria, fungi and viruses may seed the leptomeninges with tuberculosis and sarcoidosis, affecting the pia mater and arachnoid. Fungal infections often are serious and usually require hospitalization. Viral meningitis is not typically fulminant and usually has a better clinical outcome that may be treated successfully with home care. 8,126,291

IMAGING FINDINGS

MRI is more sensitive than CT in the imaging of meningitis. Contrast MRI with gadolinium (Gd-DTPA) characteristically results in diffuse enhancement of the subarachnoid space. This is not completely specific for infection; diseases such as sarcoidosis, neoplasia, or parasitic disease also may cause leptomeningeal enhancement. MRI without contrast may allow the visualization of cortical edema, distention of the subarachnoid space, and obliteration of the cisterns. 291 Inversion recovery MRI sequences are particularly sensitive to subarachnoid exudate. MRI also is adept at imaging the primary site of infection or pathology resulting from complications such as hydrocephalus, infarction, cerebritis, and empyema. 135,282

CLINICAL COMMENTS

The symptoms of meningitis are nonspecific and include headache, confusion, fever, stiff neck, nausea, vomiting, photophobia, diarrhea, seizures, and coma. Clinical signs include nuchal and spinal rigidity, Kernig’s sign, unilateral or bilateral Babinski’s sign, and Brudzinski’s sign. Petechial or purpuric skin rash may be associated with meningococcal meningitis or septicemia. Intracranial pressure may occur along with rapidly falling blood pressure, causing septic shock. In addition, systemic complications, acute cortical stroke secondary to vasospasm, and massive brain infarction may lead to death. 75

Lumbar puncture should be performed if the patient demonstrates a clinical presentation or imaging findings suggestive of meningitis. Imaging must be performed before lumbar puncture to exclude mass effect or increased intracranial pressure that may lead to herniation of the brainstem. 48 Lumbar puncture with analysis and culture of CSF should be not only diagnostic of bacterial meningitis, but a culture is essential in selecting the most effective treatment program. Septicemia is an occasional consequence of meningitis, and mortality is twice as high in cases with septicemia as with meningitis only. Early treatment with intravenous antibiotics is essential in bacterial meningitis. 8,126

• Infection of the pia mater or arachnoid causes meningitis, an extremely severe disorder.

• Magnetic resonance imaging is the most sensitive imaging examination for meningitis.

• Lumbar puncture should be performed for definitive diagnosis and to establish the most effective antibiotic treatment.

Encephalitis

BACKGROUND

Encephalitis is distinct from meningitis in that encephalitis results from inflammation of the brain parenchyma rather than the leptomeninges. However, the two often coexist, which is reflected in imaging examinations. Encephalitis is responsible for approximately 1400 deaths annually in the United States. 48 Acute encephalitis is associated more frequently with herpes simplex virus type 1 or an arbovirus than any other viral pathogen. If the infection involves the spinal cord and the brain, this is known as encephalomyelitis. Cerebritis implies a fulminant pyogenic bacterial infection that often leads to abscess formation and is not considered encephalitis. Untreated herpes simplex encephalitis has a mortality rate exceeding 50%. The mortality rate is highest in very young and elderly patients. 65,75,160

IMAGING FINDINGS

MRI is considerably more sensitive than CT in its ability to image encephalitis. Approximately 40% of the acute encephalitic lesions caused by herpes simplex are not evident on CT. Comparatively MRI has been shown to demonstrate 94% of similar lesions. 48,194 If clinical indications exist, an MRI scan should be performed even if CT is negative. Mass effect, edema, and hemorrhage are visualized in the inferior frontal and temporal lobes that may be initially unilateral with eventual spread to both sides as the disease progresses. Focal abnormalities in the basal ganglia, cerebral cortex, and substantia nigra often are discernible on MRI examination. Blood–brain barrier abnormalities are best imaged with MRI, particularly postcontrast. 48,65,150

CLINICAL COMMENTS

Symptoms are not specific for encephalitis and include sudden fever, headache, myalgia, vomiting, photophobia, stiff neck and back, confusion, drowsiness, clumsiness, unsteady gait, and irritability. Symptoms that require emergency treatment include stupor, seizure, muscle weakness, paresis, sudden severe dementia, memory loss, impaired judgment, and coma. The GCS should be used to evaluate the level of consciousness and the GCS may be beneficial in formulating a prognosis and treatment plan. Metabolic disease, immunosuppression, medication, or illicit drug use may be indicators of etiology. Lumbar puncture may be diagnostic if increased intracranial pressure or mass effect that may lead to brainstem herniation already has been excluded by advanced imaging. 48 Definitive diagnosis requires brain biopsy that exhibits a 96% sensitivity and 100% specificity. Differential considerations include a low-grade glioma, infarction, and abscess. Antiviral drugs (especially adenine arabinoside) are helpful in herpes simplex and varicella-zoster encephalitis. * The mortality rate approximates 70%. 56

• Acute encephalitis usually results from a virus.

• Magnetic resonance imaging is extremely sensitive and should be ordered, if available.

• Symptoms and signs are nonspecific.

• Brain biopsy is used for definitive diagnosis.

Epidural Abscess

BACKGROUND

An epidural abscess is a pyogenic, necrotic focus of infection superficial to the dura mater and deep to the dermal bone of the cranium or spinal canal. Most cases of intracranial epidural abscess (IEA) are secondary to direct extension from a local paranasal sinus infection, sinusitis, otitis media, mastoiditis, or dental abscess. Generalized septicemia also is a recognized cause of IEA that is often associated with pulmonary infection. Common examples include bronchiectasis, empyema, pneumonia, and bronchopleural fistula formation. IEA occasionally may be iatrogenic secondary to cranial surgery. Up to one fourth of cases of IEA are cryptogenic. Patients with a history of corticosteroids use, immunosuppressive drug therapy, and congenital or acquired immunologic deficiency are at greatest risk for IEA.

Hematogenous spread is implicated in approximately two thirds of all cases of spinal epidural abscess (SEA). The skin and supporting soft-tissue infections are the most common sources of primary infection. Direct extension of infection also has been described in association with spinal osteomyelitis, retropharyngeal abscess, perinephritic abscess, and psoas abscess. An iatrogenic SEA can occur as a complication to the administration of epidural anesthesia, lumbar puncture, and spinal epidural injection. Penetrating injuries are rarely implicated in cases of SEA. Anaerobic varieties of Streptococcus are the common causative organisms of IEA. Other pathogens include Bacteroides and Staphylococcus. Staphylococcus is the most common pathogen involved in SEA. 182,225,315

IMAGING FINDINGS

MRI scans are ideal for use in the diagnosis of both intracranial and spinal epidural abscess. Gadolinium-enhanced MRI is not only useful to demonstrate the abscess formation, but also to identify the primary site of infection. Vertebral osteomyelitis, psoas abscess, and sinusitis are readily visualized on MRI scans. The detection of these conditions should stimulate an imaging search to exclude IEA or SEA if clinical indications are present. CT with contrast is not as sensitive or specific and should be used only if MRI is not available. Plain radiographs are useful only if adjunctive disease is advanced.

Upon use of noncontrast MRI, the abscess appears as an epidural mass that is low signal on T1-weighted images and high signal on T2-weighted acquisitions. The contrasted mass may reveal diffusely homogeneous or slightly heterogenous enhancement. In later stages, enhancement may be limited to a thick rim surrounding the mass (Fig. 33-7, A and B). CT with intravenous contrast is useful in the evaluation of associated osseous involvement; however, the use of intrathecal contrast with CT may be contraindicated due to the risk of dissemination of infection. 218,275,306

|

| FIG. 33-7 Epidural abscess. The patient presented with severe low back pain 2 weeks after discectomy. A, Rounded area of intermediate signal in the T2-weighted sagittal acquisition detected posterior to the L5 vertebral body (arrow). B, Peripheral enhancement demonstrated in the postcontrast T1-weighted sagittal image (arrow). C, Abscess visualized on the right side in the axial image (arrow). High-grade central canal stenosis present on the right side. (Courtesy Bryan K. Hosler, Cincinnati, OH.) |

CLINICAL COMMENTS

An insidious onset of headache (over a period of several weeks or months) may be the only presenting complaint with IEA. A persistent fever also may be present. Nausea, vomiting, neck stiffness, focal neurologic deficit, seizure, or paresis may develop as the subdural space becomes occupied by subdural empyema. Regional signs and symptoms of a primary infection often accompany intracranial epidural abscess. Early diagnosis is essential to preclude the spread of infection to the leptomeninges or brain parenchyma.

SEA may have a similar clinical presentation to that of disc herniation. Back pain, radiculopathy, paresthesias, and cauda equina syndrome are common complaints. A febrile episode may or may not precede these complaints. Acute onset usually results from hematogenous dissemination and a more insidious onset as a result of direct extension from contiguous infection. 75,207,263,315

• Intracranial epidural abscess (IEA) usually is caused by spread of infection from adjacent sites.

• Spinal epidural abscess (SEA) is most often caused by hematogenous spread.

• Magnetic resonance imaging is more sensitive and specific than other modalities in the diagnosis of both IEA and SEA.

• Symptoms are not pathognomonic of either IEA or SEA, but should suggest appropriate imaging.

Spinal Infections

BACKGROUND

Spinal infections may involve the osseous structures (osteomyelitis), intervertebral discs (discitis), or contents of the spinal canal (epidural abscess, meningitis). Meningitis and spinal epidural abscess have been discussed previously. This section emphasizes osteomyelitis and discitis.

Although spinal infections are somewhat uncommon, it is extremely important to recognize them to minimize their potential for devastating long-term effects. Discitis and osteomyelitis typically coexist. Hematogenous osteomyelitis usually is caused by the seeding of bone from a remote site of infection. Primary infective sources commonly include the urinary tract, respiratory tract, and skin. Spread from infected tissues to contiguous structures, open trauma, or postoperative complications are other causes of spinal osteomyelitis. 85,144 Immunocompromise and intravenous drug use are precipitating factors in the development of spinal osteomyelitis. The most common organism causing vertebral osteomyelitis among newborns, children, and adults is Staphylococcus aureus. The vertebral body is richly nourished by vascular structures (both arterial and venous) and is involved in approximately 95% of cases of pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis. Posterior arch structures are infected in only 5% of all cases. 213,299 Osteomyelitis of the vascular vertebral bodies precedes discitis with the spread of infection from the osseous structures to the sparsely vascularized discs. Discitis is more prominent in males and is most commonly found, in descending order of frequency, involving the lumbar, cervical, and thoracic spine. 99,121,193

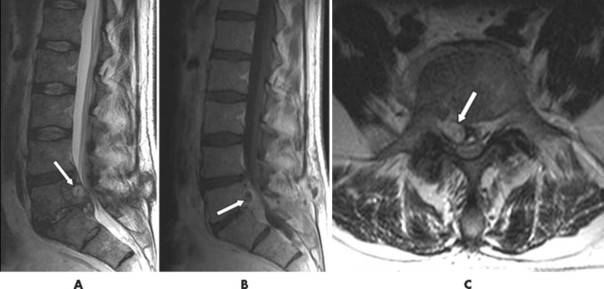

IMAGING FINDINGS

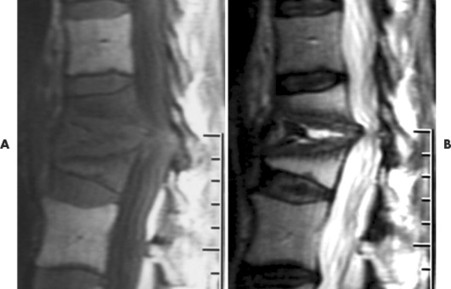

Plain film radiography may be positive in the later stages of both spinal osteomyelitis and discitis. Findings include decreased disc space height and destruction of the subjacent cortical margins. CT is more sensitive to the early detection of spinal infection than plain film radiography. In the presence of contrast enhancement, CT may be useful in the assessment of contiguous soft-tissue involvement. For early diagnosis, the imaging modalities of choice are MRI and nuclear scanning. Radionuclide scans utilizing technetium 99m and gallium 67 demonstrate uptake soon after the onset of symptoms. Nuclear imaging is sensitive; however, not as specific as MRI. MRI scans are useful not only for the early detection of early osteomyelitis and discitis, but also for contiguous soft-tissue involvement and spinal epidural abscess (Fig. 33-8, A and B). Typically, the infected vertebral structures demonstrate a low signal on T1-weighted images and a higher signal than the normal osseous structures on T2-weighted acquisitions. Similarly the infected disc has a slightly lower signal on T1-weighted images and signal is considerably increased in T2 weighting. Gadolinium contrast administration results in easily recognizable enhancement of the infected intervertebral disc and vertebral body. *

|

| FIG. 33-8 Spinal infection. A and B, Kyphotic deformity present at the thoracolumbar junction. High signal is identified within the L1-2 disc in the T2-weighted images with destruction of the adjacent vertebral bodies consistent with discitis and osteomyelitis. Retropulsion of bone and extension of infection into the spinal canal is discernible. (Courtesy Bryan K. Hosler, Cincinnati, OH.) |

CLINICAL COMMENTS

Insidious onset of back pain and minor paraspinal muscle spasm are the most common presenting complaints associated with spinal infection. The pain initially is localized to the area of infection, becoming progressively more intense with consequential limitation of motion. Regional edema, erythema, and tenderness with warmth on palpation commonly are associated clinical findings. Eventually complete bed rest and analgesics do not diminish the patient’s pain. Fever is present in approximately 50% of presenting cases, and leukocytosis may be absent or minimal. Neurologic findings are not present until late in the disease, often secondary to vertebral collapse or the intraspinal mass effect of an epidural abscess. Mass effect has the ability to compress neural structures. Epidural abscess also may lead to infarction of the spinal cord. A rapidly deteriorating neurologic deficit ensues, advancing possibly to paralysis. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) are nonspecific blood chemistry findings associated with inflammation. However, the possibility of infectious spondylodiscitis should be entertained if these tests are positive in a patient presenting with back pain. Although a blood culture is positive in only 33% to 50% of cases, it is still prudent to perform a culture before antibiotic therapy is attempted. In addition, CT-guided needle biopsy with tissue culture is indicated despite a positive return in approximately 50% of cases. 144 Surgical biopsy with débridement must be considered if the infection does not respond to intravenous antibiotic therapy, if needle aspiration biopsy does not yield an appropriate culture, if vertebral collapse occurs, or if there is neurologic compromise. 106,121,144,213,299

• Spinal osteomyelitis and discitis commonly coexist.

• Nuclear scans are sensitive.

• Magnetic resonance imaging scans are both sensitive and specific.

• Insidious onset of localized back pain with minor paraspinal muscle spasm is the most common presenting complaint.

Noninfectious Inflammatory Conditions

Multiple Sclerosis

BACKGROUND

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is the most common demyelinating disease of the central nervous system. More than 350,000 patients suffer from MS in the United States alone. The disease characteristically begins in early adulthood and is slightly more common in females. Approximately 70% of cases of MS undergo progressive exacerbation and remission of symptoms (relapsing-remitting type), whereas the remaining 30% are classified as chronic progressive. 161 It has been theorized that the etiology of MS is autoimmune, viral, genetic, or a combination of these. Evidence at this time is inconclusive, and the cause of MS still must be considered idiopathic. Environmental factors also appear to have an impact on MS, because the incidence of the disease increases in direct proportion to the distance from the equator. 64,82,287,307

A fatty substance known as myelin insulates the neural axons, promoting the virtually instantaneous transfer of neural signals. Neural conduction may be diminished or blocked completely if myelin is damaged. The primary pathologic processes of MS involve the demyelinization and inflammation of axons and the plaquing of white matter parenchyma. Plaques may be found anywhere in the white matter but are most frequent in the periventricular region of the cerebrum, brainstem, optic nerves, basal ganglia, and spinal cord. The prognosis is unpredictable. Onset at an early age, female gender, infrequent exacerbation with long remission, and a small amount of plaque visible on imaging appear to predict a relatively benign course. 82,133,161

IMAGING FINDINGS

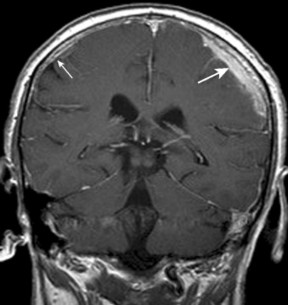

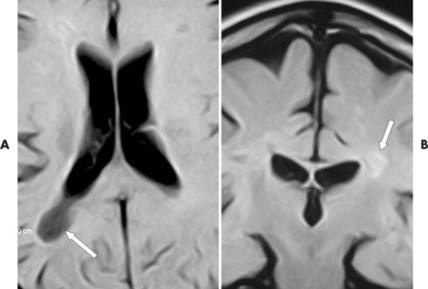

The early diagnosis of MS requires acute clinical awareness on the part of the physician. MRI is the preferred imaging modality for MS and is not only considered diagnostic but also predictive. The presence of three or more plaques in T2-weighted MR imaging is indicative that the patient will develop clinically definitive MS within 7 to 10 years. The presence of plaque is sensitive in 80% of patients who develop MS. Fifty percent of patients with MRI findings of MS are clinically definitive within 2 years. 11,161,165 Increased signal in the periventricular white matter in T2-weighted images is highly suggestive of MS. Enhancement with a gadolinium contrast is characteristic of inflammation or an active lesion (Fig. 33-9, A and B). In approximately 20% of patients with MS, CNS lesions are confined exclusively to the spinal cord. 82

|

| FIG. 33-9 Multiple sclerosis. Multiple sclerosis in a 49-year-old female patient presenting with tingling in the right arm and ataxia. A, Postinfusion T1-weighted axial acquisition displays an area of low signal (arrow) in the posterior right periventricular white matter. B, Peripheral enhancement is discernible in the lesion adjacent to the posterior horn of the right lateral ventricle in the axial image (arrow). Contrast enhancement is detected in a lesion adjacent to the left lateral ventricle visualized in the coronal image. Area without enhancement represents an old or quiescent lesion. |

MS plaques are isointense to hypointense on unenhanced T1-weighted MR images. T2-weighted and inversion recovery acquisitions reveal increased signal in MS plaques. 11 The recent advent of techniques using diffusion-weighted MRI or magnetization transfer permits earlier diagnosis of MS. These techniques take advantage of local tissue perfusion. Inflammation within the myelin sheath becomes evident before the formation of plaque and disruption of the blood–brain barrier. The size of MS plaques may be underestimated by as much as 250% on T2-weighted images compared with DWI. 165,177,314

CLINICAL COMMENTS

The clinical diagnosis of multiple sclerosis often is extremely difficult, because of a frequently variable and conflicting patient presentation. Symptoms include weakness, paresis, and tremor of one or more extremities. Muscle atrophy and spasticity may be present with dysfunctional movement. Numbness, paresthesias, and visual disturbances are common. Incoordination, myasthenia, changes in mentation, and altered speech with facial and extremity pain can occur with frequency in MS. Charcot’s triad of signs is intention tremor, nystagmus, and scanning speech (INS). The Schumacher criteria for MS consists of: (a) CNS dysfunction, (b) involvement of two or more parts of the CNS, (c) predominant white matter involvement, (d) two or more episodes lasting greater than 24 hours less than 1 month apart, (e) slow stepwise progression of signs and symptoms, and (f) onset at 10 to 50 years of age. The hallmark of MS is inconsistency in time and space. For example, a patient may present with speech difficulties and weakness of one of the extremities followed by a period of remission. On exacerbation, the patient may complain of spasticity of a different extremity with visual disturbances. Diagnosis is dependent upon the recognition of this extremely variable pattern and the judicious pursuit of appropriate laboratory testing and MRI. 82,133 Rudick red flags suggest a diagnosis other than MS: (a) absence of visual disturbances, (b) no clinical remission, (c) totally localized disease, (d) no sensory findings, (e) no bladder involvement, and (f) no CSF abnormality. Laboratory tests include lumbar puncture and evoked potentials. Oligoclonal banding and immunoglobulin G (IgG) index in the CSF are positive in approximately 90% of MS cases. Evoked potentials make use of slowed conduction in demyelinated neural structures to permit the assessment of subclinical MS. However, evoked potentials are of no value in patients with known lesions. 217

• Multiple sclerosis is a demyelinating disease of the central nervous system.

• Magnetic resonance imaging is the preferred imaging modality in the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis.

• The pattern of symptoms in multiple sclerosis is extremely variable, often characterized by relapses and remissions.

• Lumbar puncture is specific and sensitive for multiple sclerosis.

Sarcoidosis

BACKGROUND

Sarcoidosis is typically a multisystemic noncaseating epithelioid granulomatous disease process of unknown etiology. Although hilar and paratracheal lymphadenopathy are common, involvement of the lung parenchyma also may occur. Often the symptoms are less severe than the extent of chest involvement seem to suggest. Sarcoidosis of the CNS is localized to the leptomeninges with extended involvement of the brain parenchyma through the Virchow-Robin spaces. Neurosarcoidosis is found at autopsy in less than 10% of patients with sarcoidosis. The mortality rate in neurosarcoidosis is approximately 10%, double that found in sarcoidosis. 52,61,208,215,256

Contrast-enhanced MRI is the preferred modality of investigation for neurosarcoidosis. Typically, the lesions are isointense to gray matter in unenhanced T1-weighted images and isointense or slightly hyperintense in T2-weighted acquisitions. Multiple white matter lesions are detected in 43% of cases. 319 Leptomeningeal enhancement takes place with the administration of gadolinium contrast. However, other diseases may simulate neurosarcoidosis, particularly infectious meningitis and meningioma. Hypermetabolism and hypometabolism in lesional tissue are discernible with positron emission tomography (PET) scans and may be beneficial in establishing a final diagnosis. 68 Spinal involvement usually is limited to the extramedullary portion of the cervical region; however, inflammation and enlargement of the cord could suggest an intramedullary neoplasm. Lesions also may occur within the thoracic and lumbar spinal canal. 224 Atrophy of the spinal cord may be demonstrated in late-stage neurosarcoidosis. A nuclear scan with gallium 67 citrate may prove informative in equivocal cases. 130,269,303