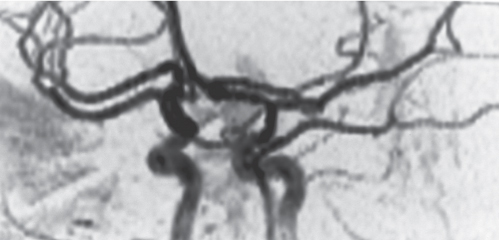

Stenosis/occlusive vascular disease |

Arterial stenosis/occlusion

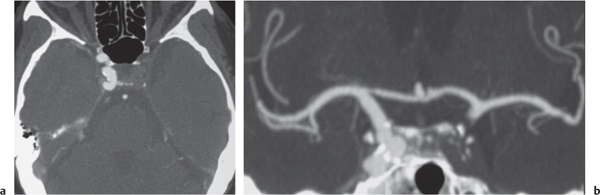

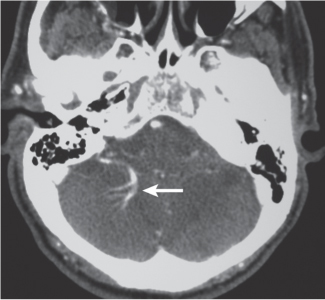

Fig. 4.10

Fig. 4.11

Fig. 4.12

Fig. 4.13

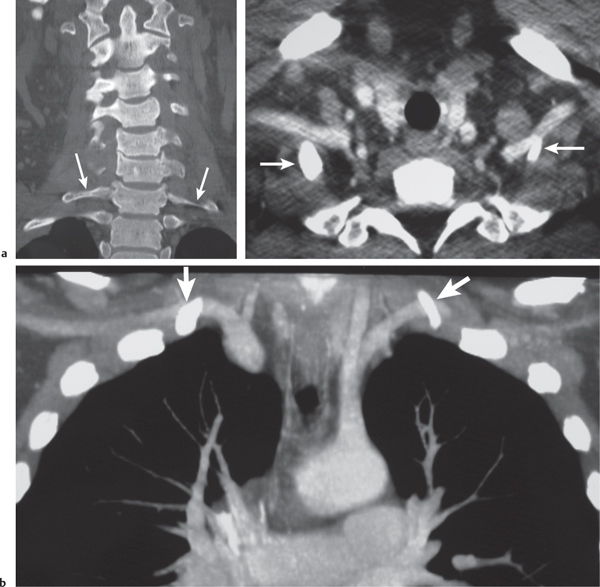

Fig. 4.14a, b |

Focal narrowing (stenosis) or absence (occlusion) of luminal contrast enhancement on CTA in artery, with or without narrowing of flow signal distal to site of stenosis. |

Arterial stenosis or occlusion may result from atherosclerosis, emboli, fibromuscular disease/dysplasia, collagen vascular disease, coagulopathy, encasement by neoplasm, surgery, or radiation injury. |

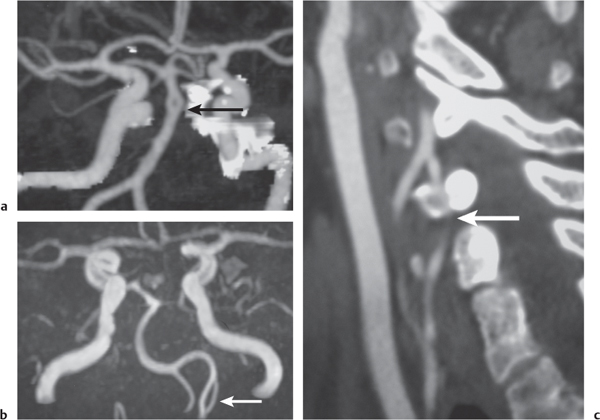

Subclavian steal syndrome

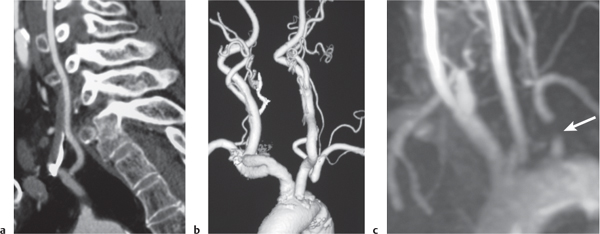

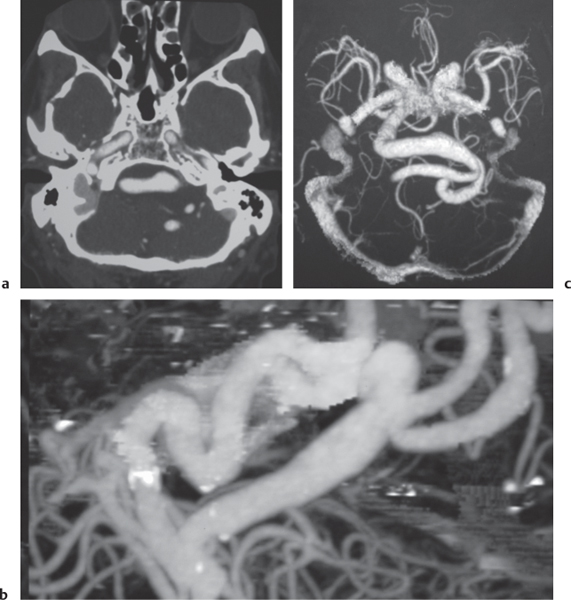

Fig. 4.15a–c |

CTA shows occlusion of the proximal subclavian artery with reconstitution beyond the occlusion via reversed blood flow from the ipsilateral vertebral artery. |

Stenosis or occlusion of the proximal subclavian artery can cause reversal of blood flow of the ipsilateral vertebral artery to supply the subclavian artery distal to the stenosis. The reversed blood flow can result in signs of vertebrobasilar insufficiency (syncope, nausea, ataxia, vertigo, diplopia, headaches, etc.) elicited with exercise of the upper extremity on the same side where the stenosis/occlusion of the subclavian artery occurs. |

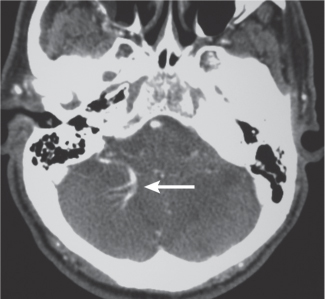

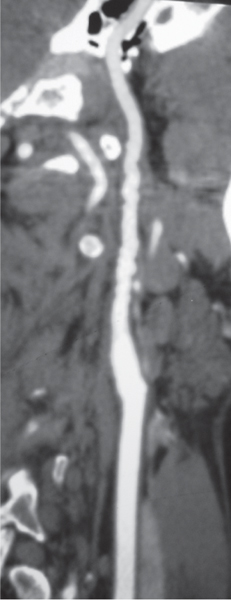

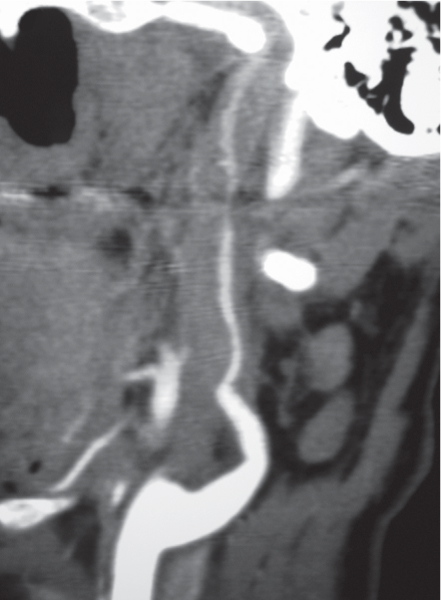

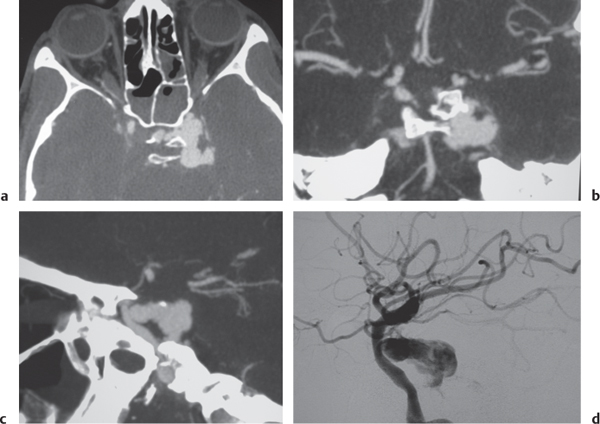

Arterial dissection

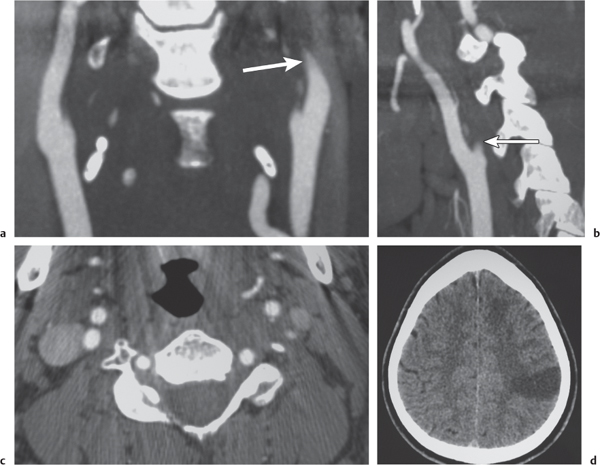

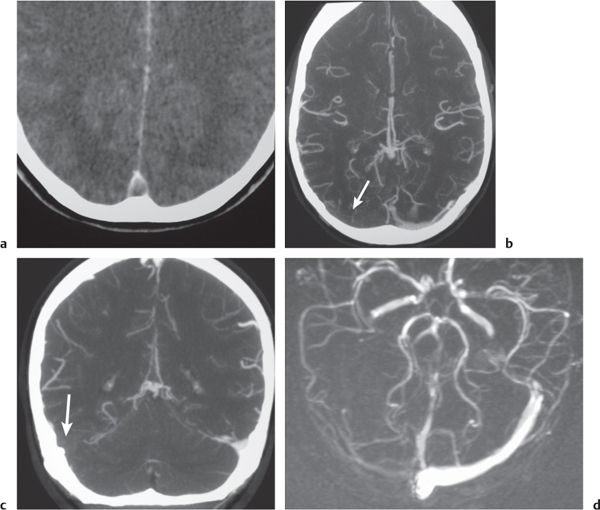

Fig. 4.16a–d |

The involved arterial wall is thickened in a circumferential or semilunar configuration and has intermediate attenuation. Lumen may be narrowed or occluded. |

Arterial dissections can be related to trauma, collagen, vascular disease (e.g., Marfan and EhlersDanlos syndromes), or idiopathic. Hemorrhage occurs in the arterial wall and can cause stenosis, occlusion, and stroke. |

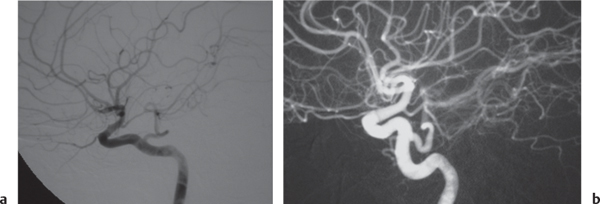

Vasculitis

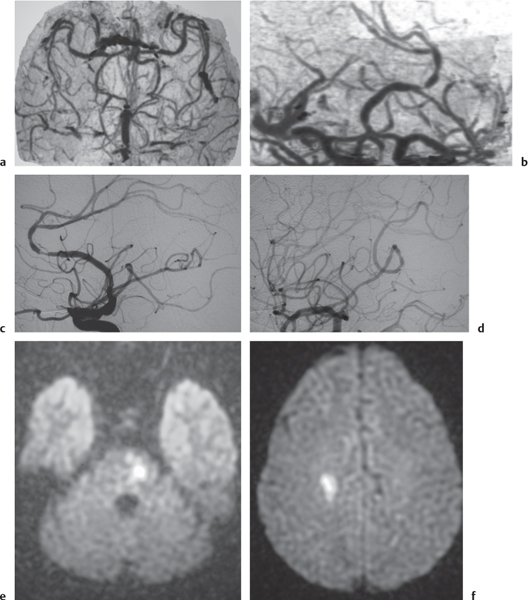

Fig. 4.17a–f |

Zones of arterial occlusion, and/or foci of stenosis and post-stenotic dilation. May involve large, medium, or small intracranial and extracranial arteries. with or without cerebral and/or cerebellar infarcts. |

Uncommon mixed group of inflammatory diseases/disorders involving the walls of cerebral blood vessels. Can result from noninfectious etiology (polyarteritis nodosa, Wegener granulomatosis, giant cell arteritis, Takayasu arteritis, sarcoid, drug-induced, etc.) or be related to infectious causes (bacteria, fungi, TB, syphilis, viral). |

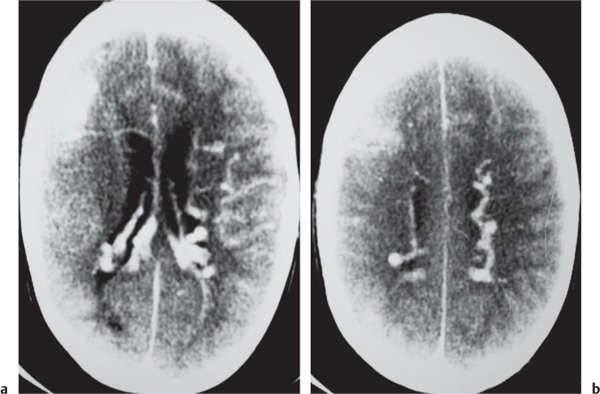

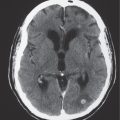

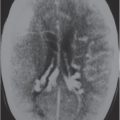

Intracranial venous sinus thrombosis

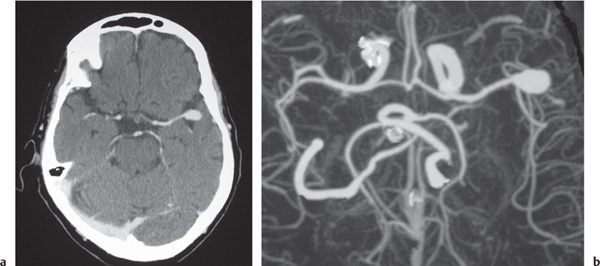

Fig. 4.18a-d |

CTA shows patent veins and venous sinuses to have high attenuation compared with zones of thrombus with lower attenuation. |

Venous sinus occlusion may result from coagulopathies, encasement or invasion by neoplasm, dehydration, and adjacent infectious/inflammatory processes. |

Aneurysms |

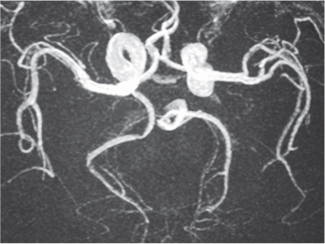

Arterial aneurysm

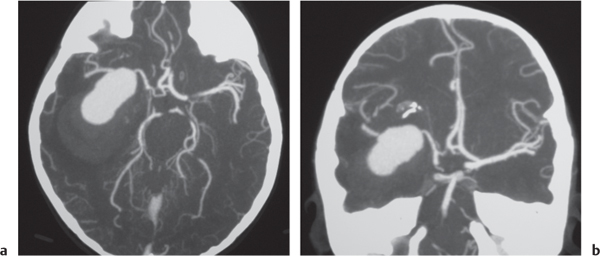

Fig. 4.19a, b

Fig. 4.20a, b

Fig. 4.21a–c |

Saccular aneurysm: Focal, well-circumscribed zone of contrast enhancement.

Fusiform aneurysm: Tubular dilation of involved artery.

Dissecting aneurysms (intramural hematoma): Initially, the involved arterial wall is thickened in a circumferential or semilunar configuration and has intermediate attenuation with luminal narrowing. Evolution of the intramural hematoma can lead to focal dilation of the arterial wall hematoma. |

Abnormal fusiform or focal saccular dilation of artery secondary to acquired/degenerative etiology, polycystic disease, connective tissue disease, atherosclerosis, trauma, infection (mycotic, oncotic), AVM, vasculitis, and drugs. Focal aneurysms are also referred to as saccular aneurysms, which typically occur at arterial bifurcations and are multiple in 20%. The chance of rupture of a saccular aneurysm causing subarachnoid hemorrhage is related to the size of the aneurysm. Saccular aneurysms > 2.5 cm in diameter are referred to as giant aneurysms. Fusiform aneurysms are often related to atherosclerosis or collagen vascular disease (e.g., Marfan and Ehlers-Danlos syndromes). Dissecting aneurysms: hemorrhage occurs in the arterial wall from incidental or significant trauma. |

Vascular malformations |

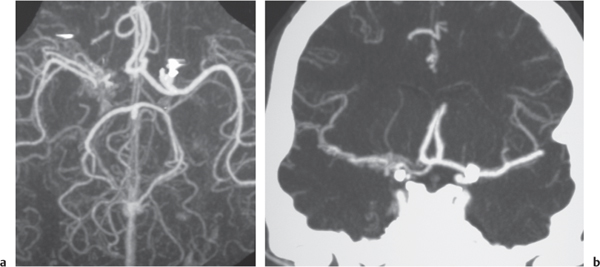

AVM

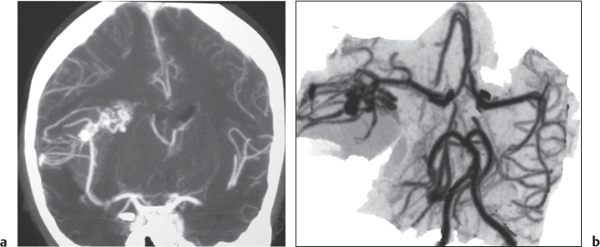

Fig. 4.22a, b

Fig. 4.23a–c |

Lesions with irregular margins that can be located in the brain parenchyma (pia, dura, or both locations). AVMs contain multiple tortuous enhancing blood vessels secondary to patent arteries with high blood flow, as well as thrombosed vessels with variable attenuation, areas of hemorrhage in various phases, calcifications, and gliosis. The venous portions often show contrast enhancement. CTA can provide additional detailed information about the nidus, feeding arteries, and draining veins, as well as the presence of associated aneurysms. Usually not associated with mass effect unless there is recent hemorrhage or venous occlusion. |

Supratentorial AVMs occur more frequently (80%–90%) than infratentorial AVMs (10%–20%). Annual risk of hemorrhage. AVMs can be sporadic, congenital, or associated with a history of trauma. Multiple AVMs can be seen in syndromes: Rendu-Osler-Weber (AVMs in brain and lungs and mucosal capillary telangiectasias) and Wyburn-Mason (AVMs in brain and retina, with cutaneous nevi). |

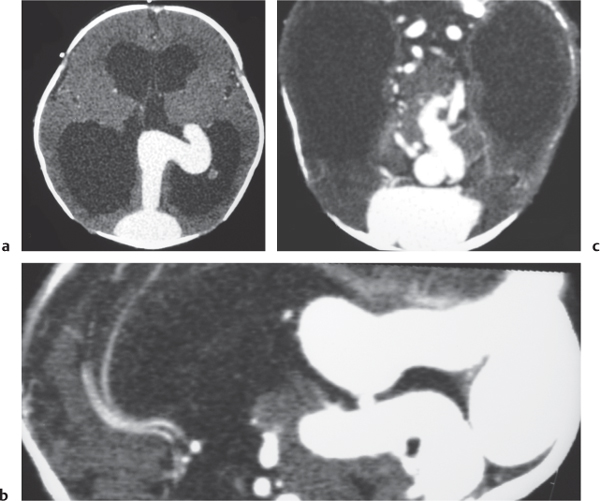

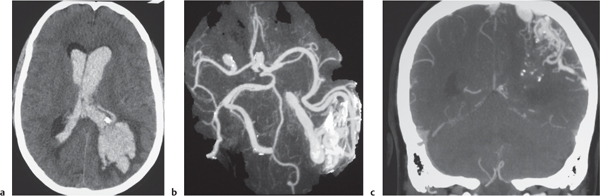

Vein of Galen aneurysm

Fig. 4.24a, b |

Multiple tortuous blood vessels involving choroidal and thalamoperforate arteries, internal cerebral veins, vein of Galen (aneurysmal formation), straight and transverse venous sinuses, and other adjacent veins and arteries. The venous portions often show contrast enhancement. CTA can show patent portions of the vascular malformation. |

Heterogeneous group of vascular malformations with arteriovenous shunts and dilated deep venous structures draining into and from an enlarged vein of Galen; with or without hydrocephalus, with or without hemorrhage, with or without macrocephaly, with or without parenchymal vascular malformation components, with or without seizures, high-output congestive heart failure in neonates. |

Dural AVM |

Dural AVMs contain multiple tortuous tubular blood vessels. The venous portions often show contrast enhancement. CTA can show patent portions of the vascular malformation and areas of venous sinus occlusion or recanalization. Usually not associated with mass effect unless there is recent hemorrhage or venous occlusion. With or without venous brain infarction. |

Dural AVMs are usually acquired lesions resulting from thrombosis or occlusion of an intracranial venous sinus with subsequent recanalization resulting in direct arterial to venous sinus communications. Transverse, sigmoid venous sinuses > cavernous sinus > straight, superior sagittal sinuses. |

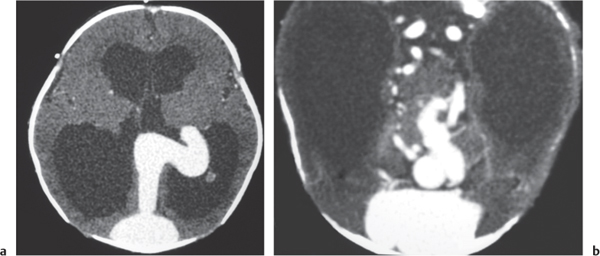

Carotid cavernous fistula

Fig. 4.25a–d |

CTA shows marked dilation of the cavernous sinuses, as well as the superior and inferior ophthalmic veins and facial veins. |

Carotid artery to cavernous sinus fistulas usually occur as a result of blunt trauma causing dissection or laceration of the cavernous portion of the internal carotid artery. Patients can present with pulsating exophthalmos. |

Cavernous hemangioma |

Single or multiple multilobulated intra-axial lesions that have intermediate to slightly increased attenuation, minimal or no contrast enhancement, with or without calcifications. |

Supratentorial cavernous angiomas occur more frequently than infratentorial lesions. Can be located in many different locations, multiple lesions > 50%. Association with venous angiomas and risk of hemorrhage. |

Venous angioma

Fig. 4.26 |

On postcontrast images, venous angiomas are seen as a contrast-enhancing transcortical vein draining a collection of small medullary veins (caput medusae). |

Considered an anomalous venous formation typically not associated with hemorrhage; usually an incidental finding except when associated with cavernous hemangioma. |

Capillary telangiectasia |

No apparent findings on noncontrast enhanced CT; may be seen as small poorly defined zones of contrast enhancement, no abnormal mass effect. |

Small venous malformations consisting of collections of dilated capillaries lacking smooth muscle and elastic fibers in walls; located in pons > other portions of brainstem, brain; typically show no enlargement over time. |