5 Neck

The structures of the neck are superficially located and easily examined with ultrasound. The retropharyngeal region is an exception because of the interposed air-filled pharynx. The deep lobe of the parotid gland is hidden behind the bony ramus of the mandible.

A high-frequency linear array transducer (15.5 MHz) can exquisitely show the structures of the neck. However, a successful examination depends for a great part on the cooperation of the patient. Patience is required. The use of warm coupling gel can be advantageous. A small pillow under the shoulders improves access to the neck but can be perceived as threatening. Its use can be postponed until a later stage of the examination.

The most common reason why an ultrasound examination is requested in our hospital is to assess the patency of the jugular and subclavian veins before the insertion of a central line. The technique is described below. The second most common reason is to evaluate a swelling. Ultrasound can in the vast majority of patients differentiate cystic from solid lesions. If considered in combination with the location of a swelling, the patient’s age, signs, and symptoms, and the laboratory data, ultrasound can often provide a straightforward diagnosis, such as a second branchial cleft cyst or fibromatosis colli.

Another common question is whether inflammation of neck structures has progressed to abscess formation.

The following paragraphs will describe the most common anomalies of the neck that are examined with ultrasound.

5.1 Normal Anatomy and Variants

The structures of the neck are easily imaged. A complete study should include the following:

The echogenic parotid gland over the ramus of the mandible ( Fig. 5.1 , Fig. 5.2 , Fig. 5.3 );

The more hypoechoic and coarse submandibular gland at the tip of the parotid gland, medial to the mandibular angle ( Fig. 5.4 and Fig. 5.5 );

The sublingual gland in the floor of the mouth ( Fig. 5.6 and Fig. 5.7 );

The homogeneous echogenic thyroid gland in the midline in the lower neck ( Fig. 5.8 , Fig. 5.9 );

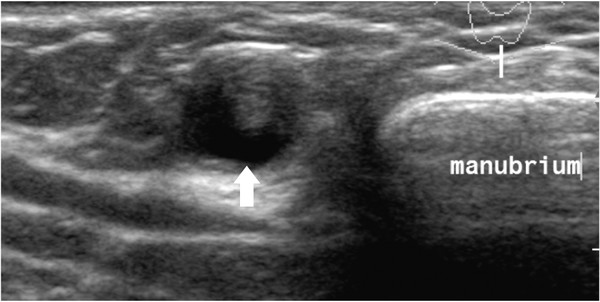

The more hypoechoic thymus in the suprasternal notch ( Fig. 5.10 , Fig. 5.11 );

The carotid and subclavian arteries and the jugular and subclavian veins ( Fig. 5.12 , Fig. 5.13 , Fig. 5.14 , Fig. 5.15 , Fig. 5.16 ).

In healthy children, lymph nodes are almost invariably present. A large node is located laterally under the floor of the mouth, just behind the meeting point of the parotid and submandibular glands. See the section on lymphadenopathy.

Tips from the Pro

Use the highest-frequency linear array transducer that still shows enough of the deeper structures.

5.2 Pathology

5.2.1 Vessels of the Neck

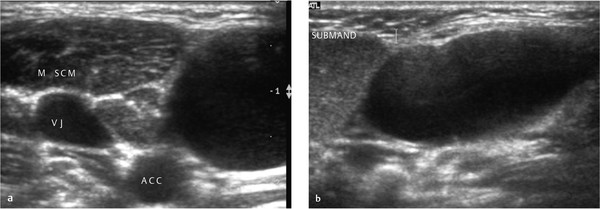

One of the most common reasons why ultrasound of the neck is requested is to demonstrate patency of the jugular, subclavian, and brachiocephalic veins before the insertion of a central venous line. The examination is generally easy to perform, although restlessness of the child can pose a problem, especially if combined with crying, which hampers Doppler measurements.

The internal jugular vein is easily seen lateral to the common carotid artery. The right jugular vein is usually larger than the left jugular vein. The distal subclavian vein can be picked up in the sagittal plane below the collar bone, superficial and caudal to the subclavian artery. After redirection of the transducer along the length of the vein, Doppler measurements can be done. More medially, the subclavian vein can be seen from a window above the collar bone, and its confluence with the jugular vein. The left brachiocephalic vein is seen when the neck of the child is extended or a pillow is placed under the shoulder blades. The superior caval vein can be seen in infants through the thymus, but in older children, it is often hidden behind the lung.

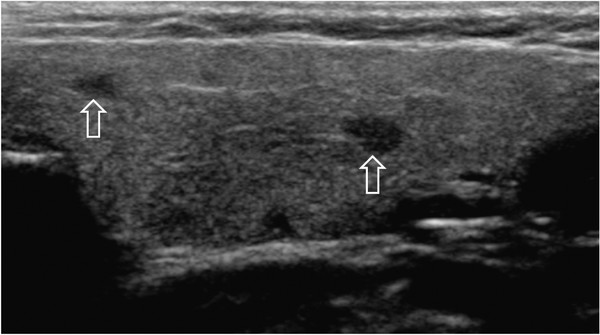

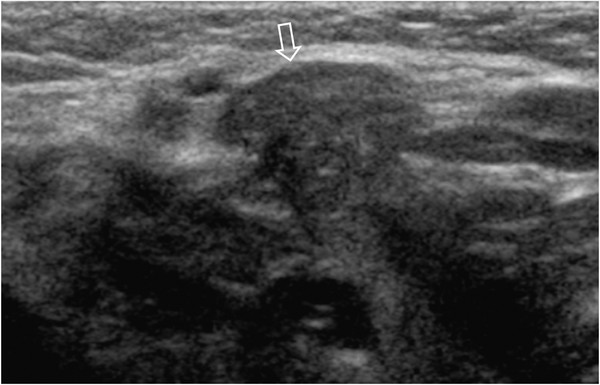

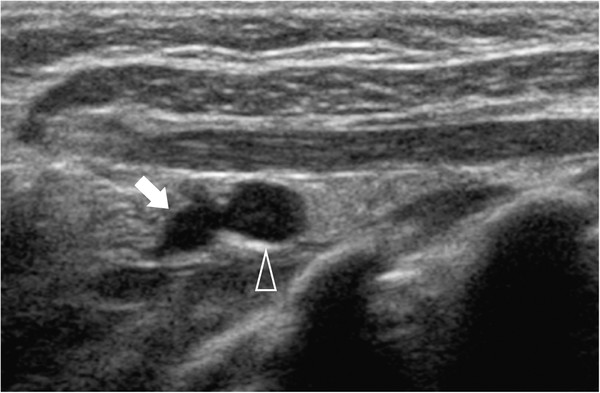

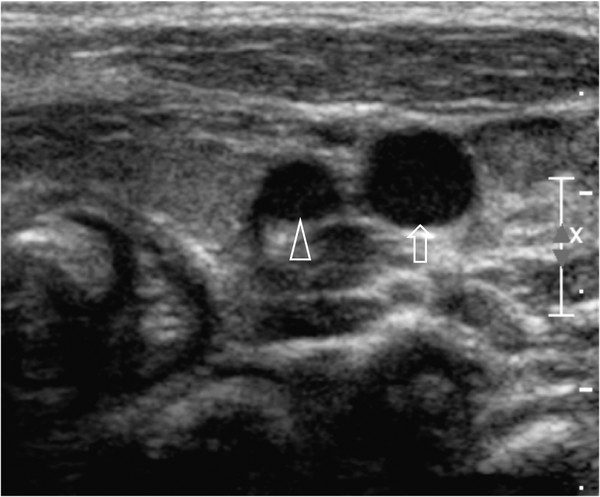

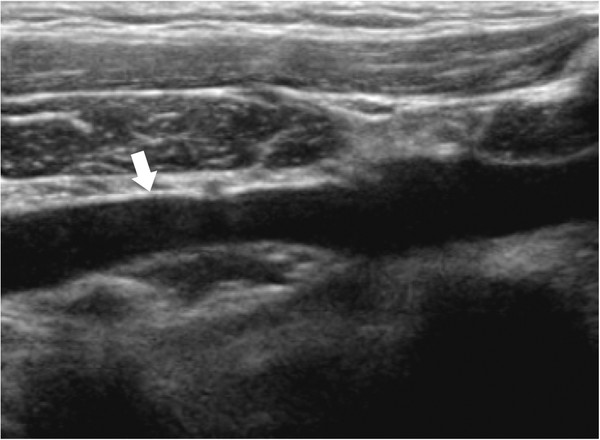

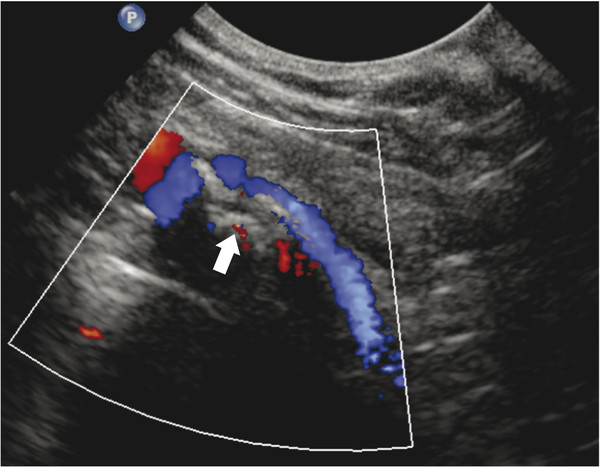

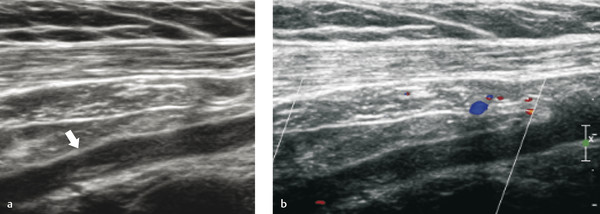

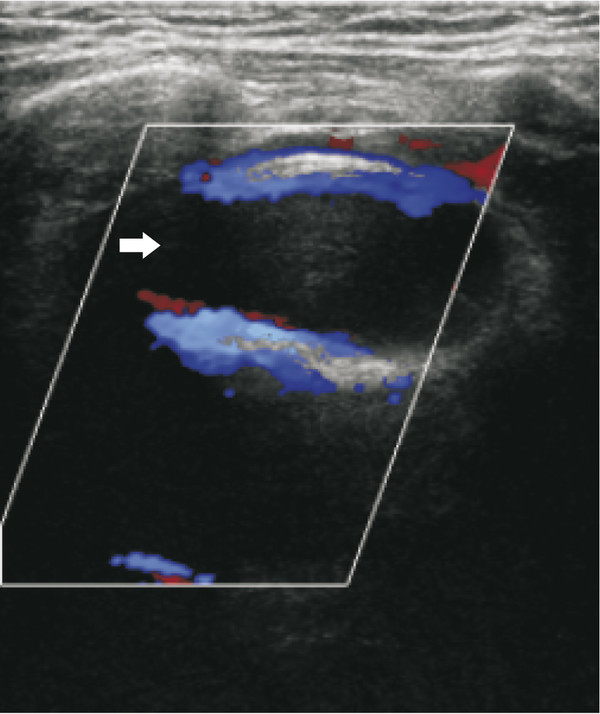

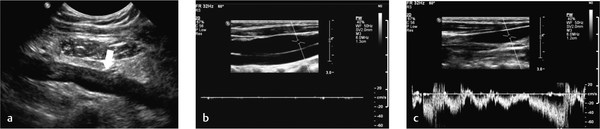

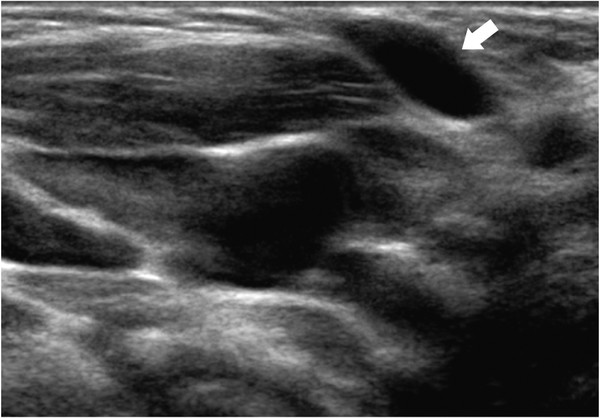

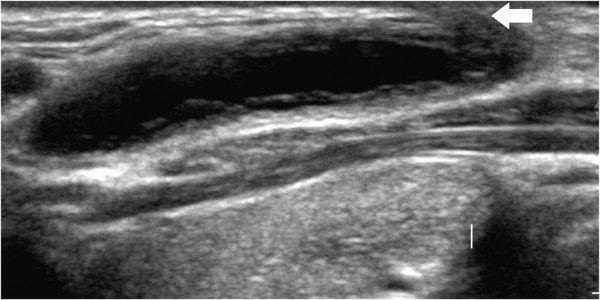

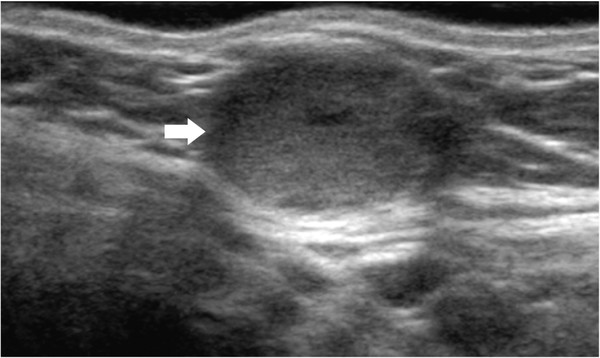

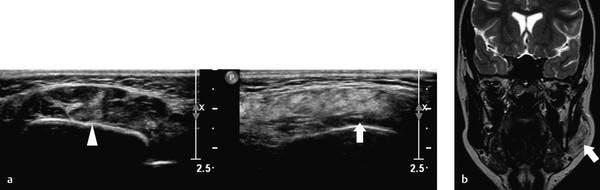

Normal veins vary in caliber with the respiratory cycle. Thrombosed veins do not collapse and cannot be compressed. A thrombus is echogenic ( Fig. 5.17 ), although fresh thrombus can be almost anechoic ( Fig. 5.18 , Fig. 5.19 , Fig. 5.20 ). In thrombosis, collaterals can be present, but a collateral vein can be mistaken for the normal vein. Look for the presence of superficial veins in a patient as a sign of collateral circulation. A thrombosis can be clinically occult.

Sometimes, a large swelling can be seen laterally in the lower neck when a child is crying or pushing. Ultrasound can demonstrate an enlarged, ectatic external jugular vein.

Tips from the Pro

If you are requested to look for a thrombus at the tip of a central venous line, study a plain chest film to locate the tip before you start your sonographic examination.

Know the location of normal veins, and do not mistake a collateral vein for a patent normal vein.

5.2.2 Cystic Lesions

Thyroglossal Duct Cyst

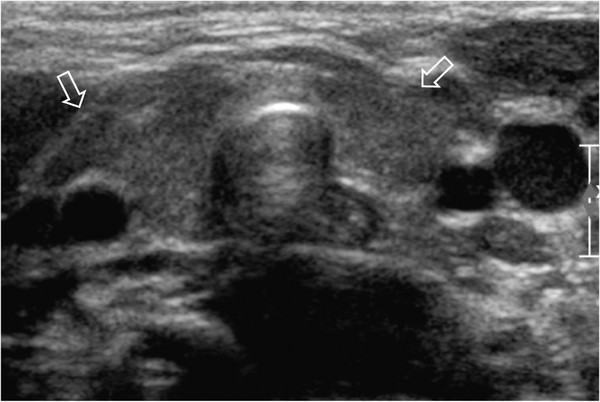

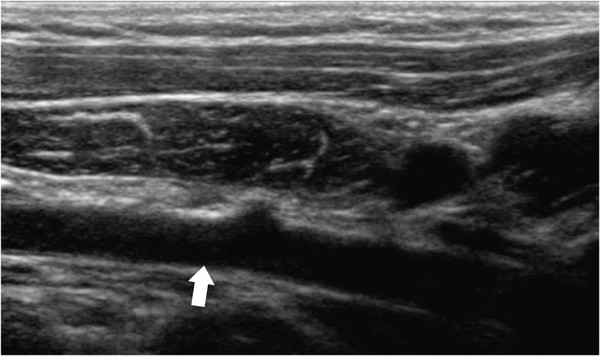

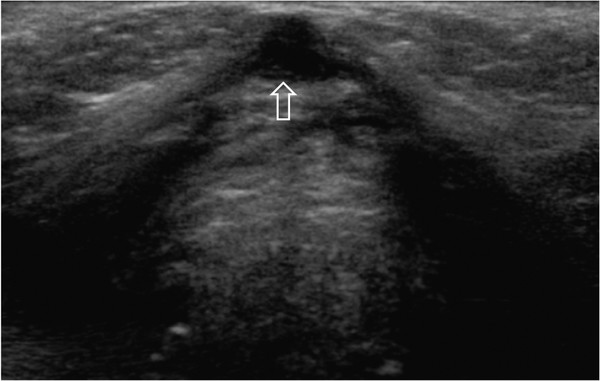

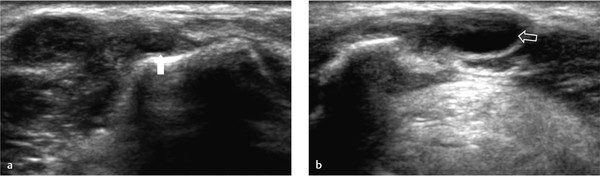

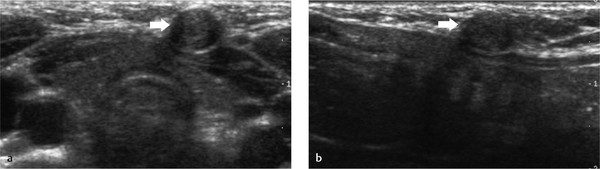

A thyroglossal duct cyst is a remnant of the thyroid gland that is detached during the descent of the gland from the base of the tongue to the lower neck. The cyst is located within 2 cm of the midline. Most are exactly in the midline between the thyroid gland and the hyoid bone, but they can occur above the level of the hyoid bone. The contents can be clear or cloudy, especially after being infected ( Fig. 5.21 , Fig. 5.22 , Fig. 5.23 , Fig. 5.24 ). The cyst should move upward during swallowing. The differential diagnosis of a thyroglossal duct cyst is epidermoid or dermoid cyst.

In postoperative patients, imaging is more difficult. Sometimes, a cystic lesion is visible, but on other occasions an unclear clump of tissue with variable echogenicity is seen ( Fig. 5.25 ).

Always image the thyroid gland itself because anecdotal stories tell of patients whose only ectopic thyroid tissue was located in the cyst itself. If a normal thyroid gland is demonstrated with ultrasound, then confirmation with radionuclear imaging is not necessary.

Cysts are treated surgically with a Sistrunk procedure, which entails excision of the cyst and its track along with the central part of the hyoid bone.

Branchial Cleft Cyst

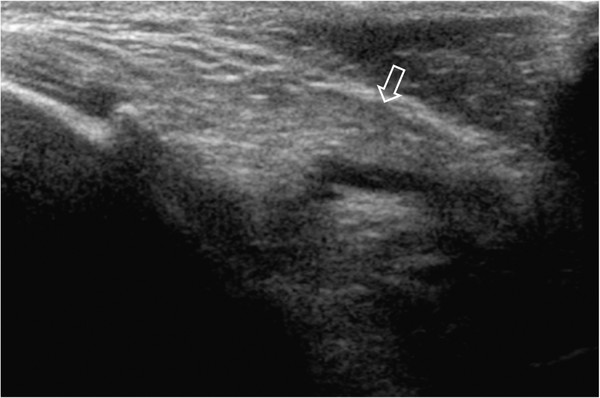

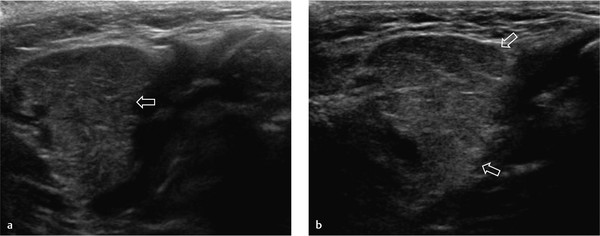

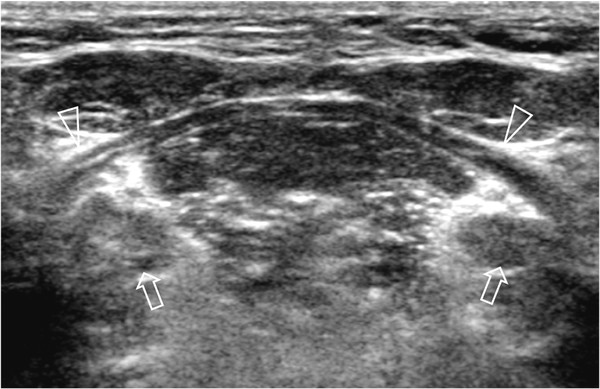

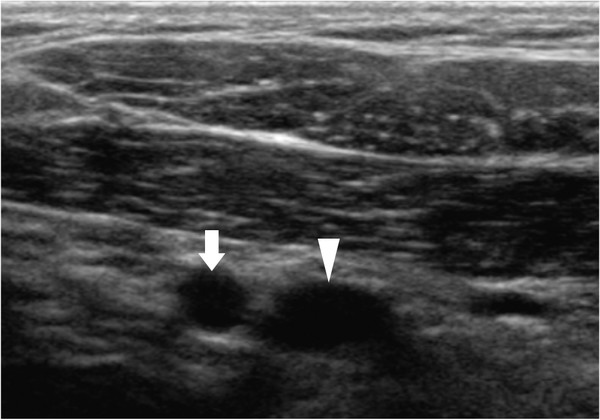

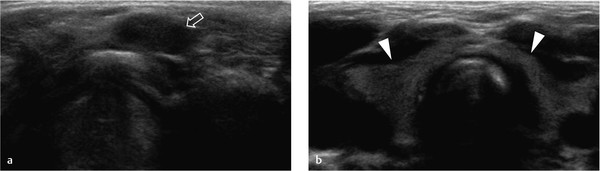

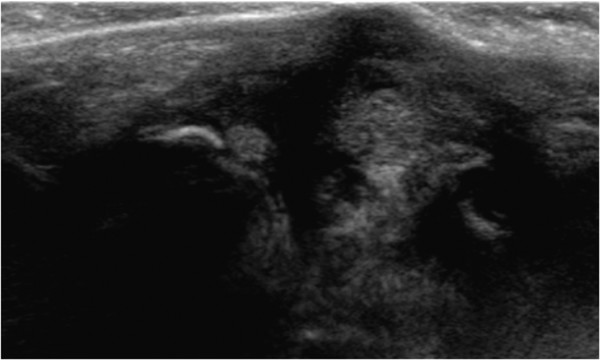

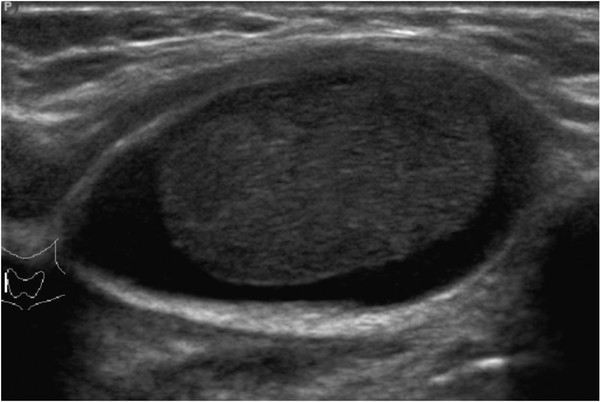

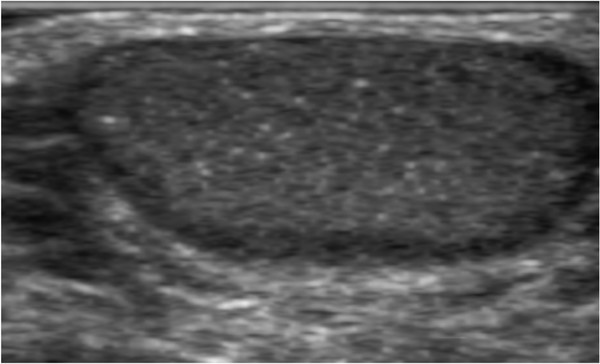

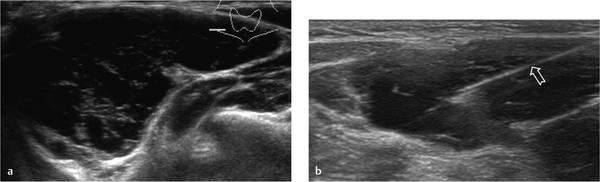

Branchial cleft cysts develop from remnants of the branchial apparatus. Most common are cysts of the second branchial arch and pouch. These lesions usually present in teenagers as a slowly growing mass in the lateral neck or, when infected, as a painful swelling where no tumor was noted before. The location of the cyst is anteromedial to the sternocleidomastoid muscle and anterolateral to the carotid artery and jugular vein ( Fig. 5.26 ). Although a cyst, it usually contains debris ( Fig. 5.27 ). It is sharply demarcated with a thin wall. Ultrasound can be helpful during treatment with sclerosing agents. If the cyst is infected, the wall thickens, with increased flow seen on color Doppler. Debris will be present.

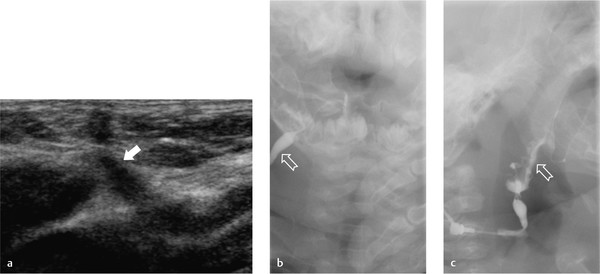

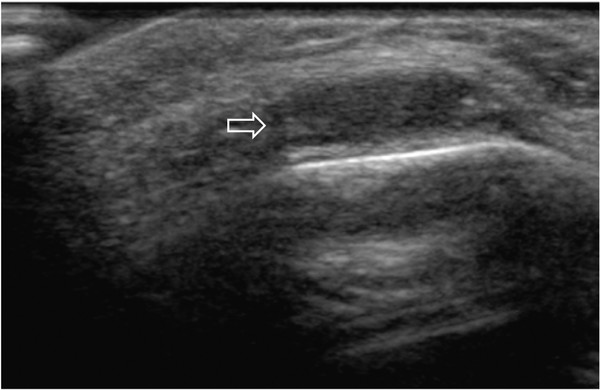

Cysts from the first, third, and fourth arches are less frequent. Sinus and fistulas can be present ( Fig. 5.28 , Fig. 5.29 , Fig. 5.30 ). Ultrasound can demonstrate accompanying cysts, but in producing fistulas, a contrast fistulogram is indicated to demonstrate the tract and a possible connection to the pharynx. This diagnosis is very difficult with ultrasound.

Dermoid Cyst

A dermoid cyst is a cystic teratoma that contains developmentally mature skin and adnexa of the skin, such as sweat glands, hair follicles, hair, and sebaceous glands. Dermoid cysts are benign. An epidermoid cyst is lined by epithelium and contains keratin. Calcifications are absent.

In the head and neck region, two types of dermoid cyst occur: orbital cysts and cysts in the subcutaneous tissue, often in the floor of the mouth or suprasternal notch. The most common site for an orbital dermoid cyst is at the lateral eyebrow, where it develops around the zygomaticofrontal suture. The cyst can also present at the medial orbit or on the skull.

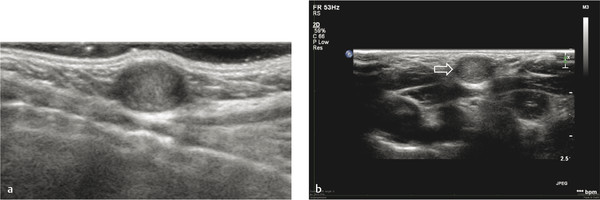

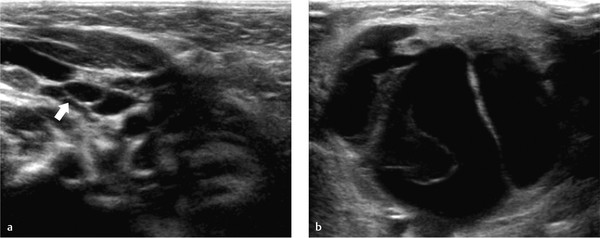

On ultrasound, the lesion is sharply demarcated, oval, and hypoechoic (see Fig. 5.30 ). Where the tumor abuts the skull, a depression of the bone is often visible. A very hyperechoic inner border of the cyst does not necessarily mean that the bone is intact. The dura is also very echogenic. If the cyst is near the midline and one is unsure whether it has eroded through the skull, additional computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance (MR) imaging is indicated. These imaging methods can also demonstrate an encephalocele.

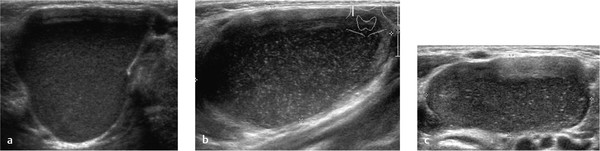

Dermoid cysts ( Fig. 5.31 , Fig. 5.32 , Fig. 5.33 , Fig. 5.34 , Fig. 5.35 , Fig. 5.36 , Fig. 5.37 ) in the neck region are usually in the midline. The tumor is smooth and oval or round, and its contents can be of any echogenicity. It can be homogeneous or mixed because of its contents, which may be fat, hair, blood, keratin, or something else. If a dermoid cyst is found between the hyoid bone and the thyroid gland, differentiation from a thyroglossal duct cyst is difficult. CT or MR imaging can show fatty content in a dermoid cyst; fat is not present in thyroglossal duct cysts.

5.2.3 Hemangiomas and Vascular Malformations

Hemangiomas and vascular malformations are both endothelial malformations. Today, the classification of Mulliken is used. He described a division into hemangiomas and vascular malformations. The latter can be further divided into capillary, venous, arteriovenous, lymphatic, and mixed malformations and fistulas. In the case of vascular malformations, a separation into high-flow lesions and low-flow lesions is even more important. High-flow lesions have an arterial component. Low-flow lesions do not have an arterial component.

Hemangiomas are often called infantile hemangiomas because of the age at which they appear. They are small or absent at birth. They increase in size during the first year of life. Thereafter, they slowly decrease in size and can disappear, often leaving a fibrofatty scar. If they occur in places where their increasing size poses clinical problems, such as around the orbit or near the airway, treatment is necessary. For the past few years, β-blockers have been the first line of treatment.

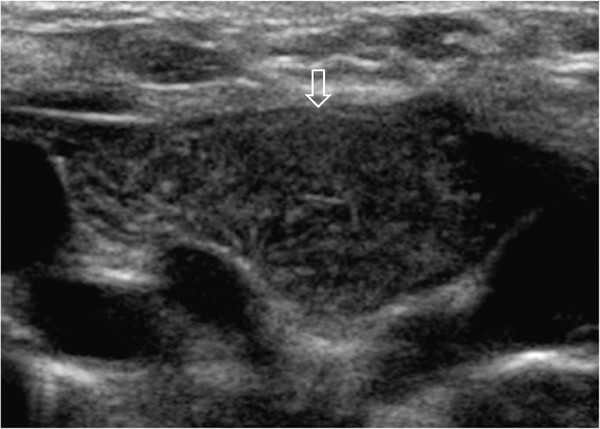

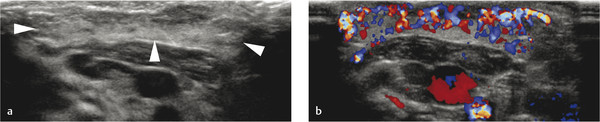

On ultrasound, infantile hemangiomas in the infant are richly perfused tumors ( Fig. 5.38 and Fig. 5.39 ). Ultrasound can show their extent into deeper tissues. If there is any doubt about this, MR imaging is indicated. On color Doppler, the involution of a hemangioma is signaled by decreased perfusion of the mass.

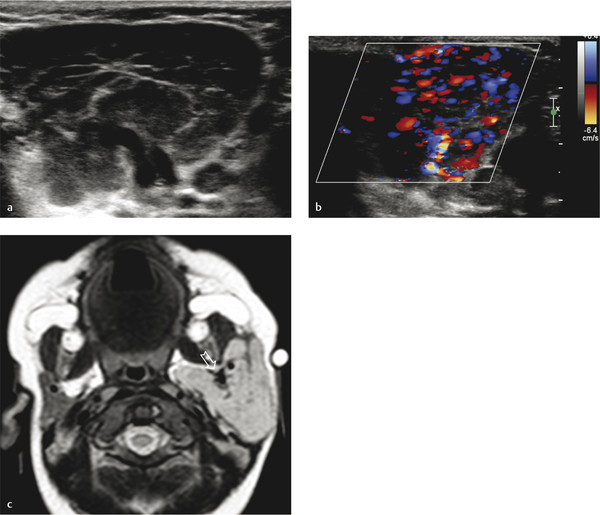

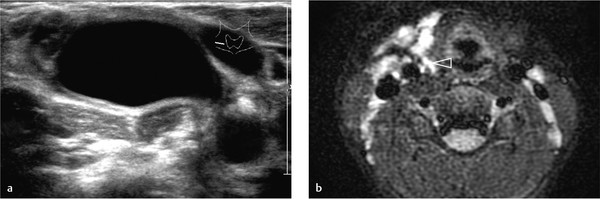

Vascular malformations are present at birth and grow proportionally with the child. They can be asymptomatic or cause symptoms, sometimes at an older age. Ultrasound can show the extent of a lesion, but if this is unclear, MR imaging should be employed ( Fig. 5.40 and Fig. 5.41 ). Doppler ultrasound can demonstrate the presence of arterial Doppler signals and direct further imaging. If Doppler ultrasound shows arterial waveforms suggesting a high-flow lesion, angiography should be done to determine if transarterial embolization is feasible. If Doppler ultrasound shows a low-flow lesion, direct puncture under ultrasound can be done, followed by phlebography and, if possible, sclerosis. Excision is another therapeutic option.

Vascular malformations, especially those with predominantly venous components, can be difficult to depict because they are easily compressed. Use a lot of gel and just touch the lesion lightly.

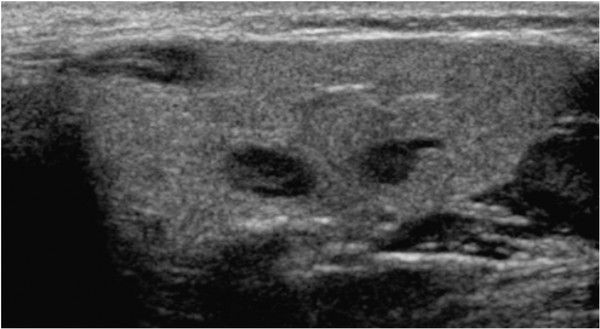

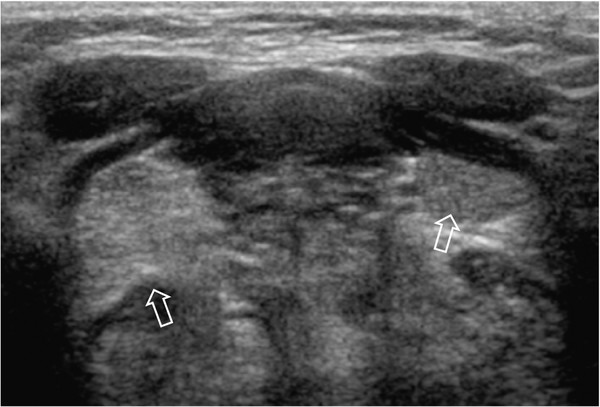

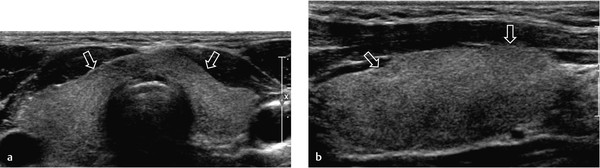

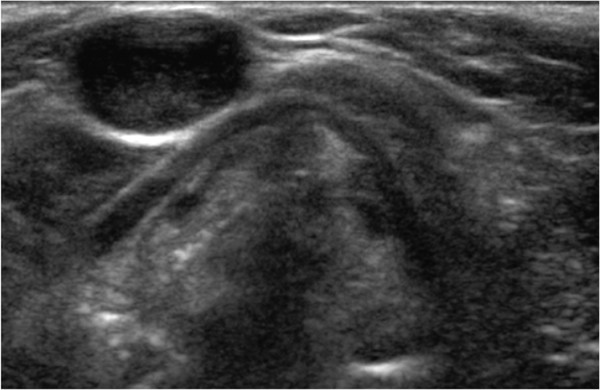

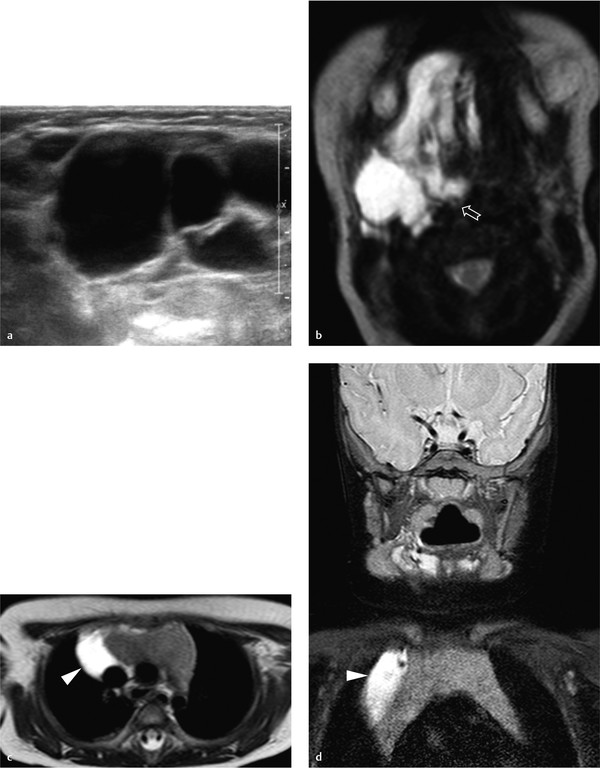

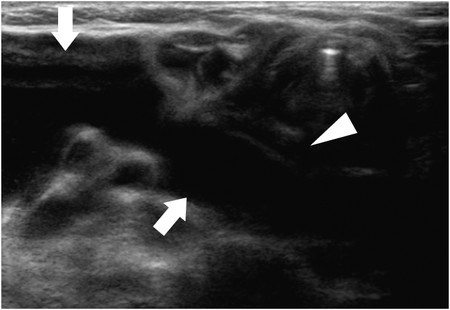

Lesions with mostly lymphatic components, also called lymphangiomas, cannot be easily compressed ( Fig. 5.42 , Fig. 5.43 , Fig. 5.44 , Fig. 5.45 ). In infancy, a multicystic form occurs, composed of innumerable small cysts. This lesion is often apparent at birth as a gross swelling of the neck and is also known as hygroma colli. In older children, lymphangiomas appear mostly in the posterior neck and consist of one or more larger cysts.

Lymphangiomas can extend much farther than ultrasound shows. If there is any doubt about the extent of a tumor, additional MR imaging is indicated.

Surgery is the primary treatment for hygroma colli, but the operation can be difficult because the tumor has a tendency to infiltrate the deeper tissues (see Fig. 5.42 ). The form with larger cysts can be surgically removed, but aspiration and injection with a sclerosing agent is also done (see Fig. 5.43 , Fig. 5.44 , Fig. 5.45 ).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree