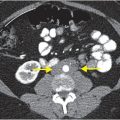

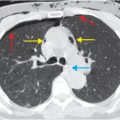

Diagnosis: Perforated duodenal ulcer

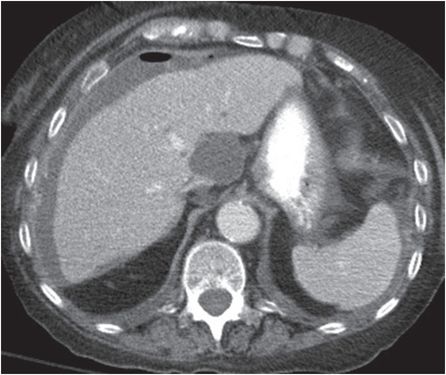

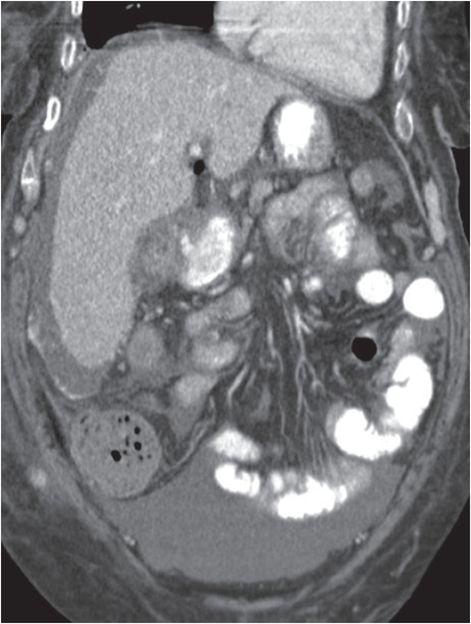

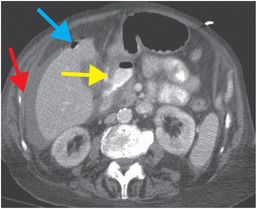

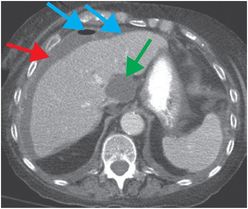

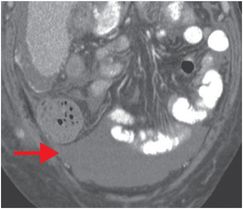

Axial and coronal oral and intravenous contrast-enhanced CT images show a thickened duodenal wall, with oral contrast extravasating through a wall defect (yellow arrow). There is perihepatic and pelvic ascites (red arrows), with several locules of gas (blue arrows) in the prehepatic space indicating pneumoperitoneum. A focal portocaval fluid collection (green arrow) compresses the inferior vena cava.

Discussion

Overview of peptic ulcer disease

The most common cause of nontraumatic gastrointestinal tract perforation is perforated duodenal ulcer.

The vast majority of duodenal ulcers are related to Helicobacter pylori infection, with a markedly reduced incidence in the past decades due to treatment with antibiotics and acid blocker medications. Other risk factors for duodenal ulcer disease include alcohol, smoking, and chronic corticosteroids. Duodenal ulcers and gastric ulcers share risk factors; however, duodenal ulcers are approximately 2–3 times more common than gastric ulcers, and duodenal peptic ulcers are less commonly malignant in comparison to gastric ulcers.

Duodenal ulcers occur most frequently in the duodenal bulb. Ulcers distal to the duodenal bulb are suspicious for Crohn’s disease or Zollinger–Ellison syndrome, and ulcers distal to the ampulla of Vater are very rare but should raise concern for duodenal adenocarcinoma. Secondary inflammation of the duodenum, which may be seen in pancreatitis, tends to be more diffuse than inflammation in primary ulcer disease.

Complications of untreated duodenal ulcer include bleeding, rupture, and stricture that may lead to gastric outlet obstruction. Perforation of the anterior duodenal wall may lead to peritonitis and pneumoperitoneum, whereas perforation of the posterior wall may lead to catastrophic bleeding from injury to the gastroduodenal artery, which lies posterior to the first portion of the duodenum.

Treatment of ruptured duodenal ulcer is typically emergent surgery; however, percutaneous drainage may be performed in patients who are poor surgical candidates.

Imaging of peptic ulcer disease

Uncomplicated duodenal peptic ulcer disease may be difficult to diagnose by CT because mucosal ulcers and wall thickening are most often not apparent. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy has higher sensitivity for uncomplicated peptic ulcer disease. CT is reserved for evaluation of patients with signs and symptoms of complicated disease.

CT findings of perforated duodenal ulcer include focal mural thickening, periduodenal fluid, and free peritoneal or retroperitoneal gas (the majority of the duodenum is retroperitoneal—only the proximal segment of the first portion of the duodenum is intraperitoneal). If enteric contrast is administered, there may be free extravasation of contrast through the mural defect, as in the index case; however, this finding is unusual.

Clinical synopsis

The patient was determined to be a high-risk surgical candidate due to her concomitant pulmonary insufficiency. Several image-guided percutaneous periduodenal fluid collection drainages were performed. There was no significant improvement in her tenuous clinical status, and the patient died approximately 10 days later from vancomycin-resistant enterococcus sepsis.

Self-assessment

|

|

|

|

|

|

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree