6 Trauma and Hemorrhage

6.1 Introduction

Traumatic head injuries are a common occurrence, with an incidence of up to 1.7 million per year in the United States as of 2014. 1 ,? 2 Trauma results in costs for early, follow-up, and possibly long-term care, and also has implications with regard to neural development. Head trauma comes in many forms and has many causes, including accidents and sports injuries. Another type of traumatic injury is purposeful trauma, also known as nonaccidental trauma (NAT) or child abuse. The appearance of the developing skull makes it common for unfused sutures to be mistaken for fractures in young children, and conversely, fractures can be mistaken for normal sutures. Radiolographic evaluation plays a critical role in the diagnosis and characterization of traumatic head injury, and research has suggested an even larger role for it in the future with advanced imaging techniques. 3 ,? 4 ,? 5 A correct understanding of normal developmental anatomy throughout childhood, as well as of the various types of intracranial injuries in pediatric trauma, can allow the appropriate identification of injuries, aiding in their treatment and prognosis.

6.2 Hemorrhage

6.2.1 Appearance of Blood on Computed Tomography

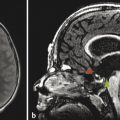

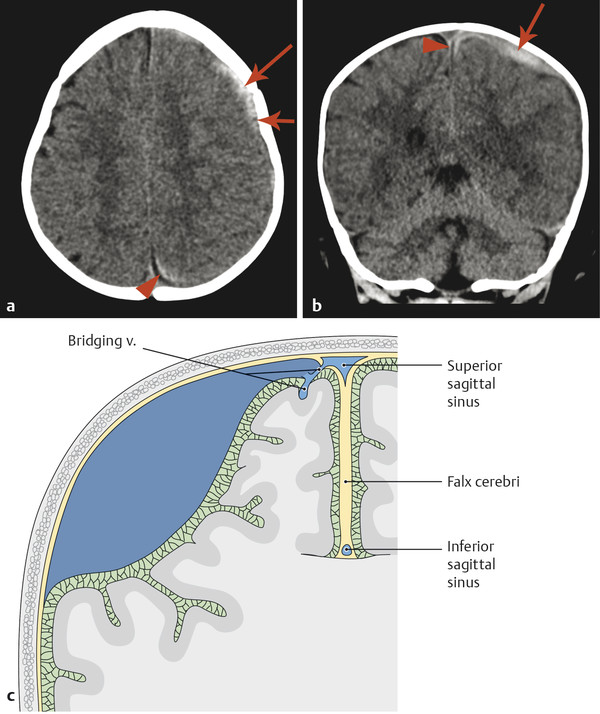

Acutely clotted blood has a density on computed tomography (CT) that is higher than that of brain parenchyma, typically up to 60 to 80 HU. The density is related to the concentrated proteins and heme (which contains iron) in the clot. Unclotted blood will not have this high density, and a hyperacute hemorrhage may not have a uniformly high density, as is the case with the “swirl-sign” of active bleeding into an epidural hematoma (Fig. 6.1). Over time, a hematoma will evolve and decrease in size, and the protein and heme in it are resorbed, resulting in the density of the collected blood decreasing at approximate 1 HU per day. A collection of intermediate density (perhaps 30 HU) is commonly said to be a chronic collection, but may represent an acute collection in a patient with severe anemia.

6.2.2 Dating Hemorrhage on Magnetic Resonance Imaging

The appearance on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of evolving blood products relates to both the chemical species of heme in an image and the integrity of the erythrocyte. The evolution of hemoglobin from oxyhemoglobin to deoxyhemoglobin to methemoglobin and then to hemosiderin occurs in a sequential manner but with a highly variable time frame (Table 6-1). Additionally, there is cell lysis, typically during the methemoglobin stage of the evolution. The timing with which the entities in the evolution appear depends upon factors like the presence of continuing bleeding, temperature, pH, and oxygen tension, among others. It is therefore strongly recommended that exact dating of blood products not be attempted with MRI, and even an approximate time window should be suggested with caution in the absence of a full understanding of all of the factors that influence the evolution of blood. Mnemonics exist to assist in remembering the appearance of blood at various stages in T1 W and T2 W images; however, using a mnemonic for this reflects a lack of understanding the process in which blood products evolve, and no attempt should be made to date the blood products if using a mnemonic approach. We will focus on T1 W and T2 W imaging, and later deal with susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI).

Blood product | T1-weighted imaging | T2-weighted imaging | Approximate time frame | |

Hyperacute | Oxyhemoglobin | Isointense | Hyperintense (with a possible hypointense rim) | 4–6 h |

Acute | Deoxyhemoglobin | Isointense | Hypointense | 6 h–3 days |

Early subacute | Intracellular methemoglobin | Hyperintense | Hypointense | 3–7 days |

Late subacute | Extracellular methemoglobin | Hyperintense | Hyperintense | 1–6 weeks |

Chronic | Hemosiderin | Hypointense | Hypointense | Months to forever |

Oxyhemoglobin is present in the first few hours after bleeding. Within a few hours, the oxyhemoglobin degrades to deoxyhemoglobin, which has a hyperintense signal on T1 W MRI. This evolution takes longer in environments with higher pO2 values. After 1 to 5 days, deoxyhemoglobin metabolizes to methemoglobin. Because of proton–electron dipole–dipole interaction (PEDDI), methemoglobin is bright on T1 W imaging. Its hyperintense signal on T1 W imaging is due to PEDDI, but with intact erythrocytes, methemoglobin has hypointense T2 W imaging because of proton relaxation enhancement (PRE). When the erythrocytes lyse, PRE is no longer a factor in the T2 W signal, which then becomes hyperintense. The shortening of the T1 W signal caused by PEDDI is related to the methemoglobin itself and is unaffected by cell lysis. Eventually, the methemoglobin evolves into hemosiderin, which is hypointense on T1 W and T2 W imaging as well as on SWI. Not only is the exact timing of this evolution highly variable, but the evolution of different portions of a hematoma may vary because all of the chemical species in it do not evolve simultaneously.

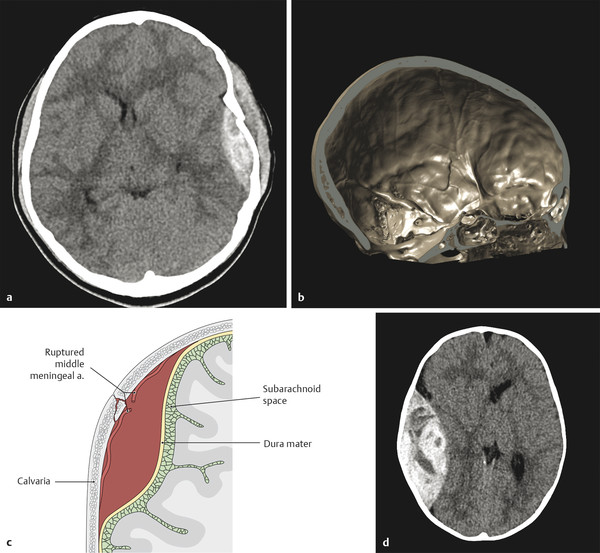

6.2.3 Subdural Hematoma

A subdural hematoma (SDH) is a collection of blood between the inner and outer dural layers, most commonly related to the traumatic injury of bridging veins. The blood collection that produces an SDH is most commonly located directly subjacent to the site of injury, but with the development of communication of the subdural space, the blood collection in an SDH can redistribute. Subdural hematomas are typically characterized by their location, thickness, and resulting mass effect. These collections are typically of low pressure, filled from venous bleeding, and have a crescentic shape. Because the blood collections in SDH are of low pressure and often do not grow, they are typically followed clinically in the absence of a marked mass effect or neurologic symptoms. However, an SDH can be evacuated neurosurgically if there is concern for its enlargement, a significant mass effect, or a neurologic deficit.

The margins of the falx cerebri and tentorium cerebelli are covered with dural layers, and subdural collections of blood can commonly be seen along these structures (Fig. 6.2). Because the subdural space courses along the surface of these structures, a collection that extends across the falx cerebri or tentorium cerebelli without extension overlying the surface is within the epidural space (Fig. 6.3). Trace subdural blood products overlying the occipital poles and cerebellum can be seen in the early postnatal period in relation to parturition (see Chapter 5), but there will typically be no parenchymal abnormality or resulting mass effect in such cases.

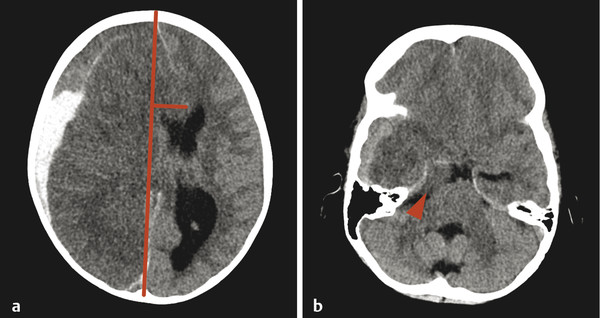

An entity that occurs in young children but rarely in adults is a subdural hematoma with a focal tear in the dural membrane that allows cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) to extend into the subdural space. This is known as a hematohygroma; it can be of lower density on CT than typically expected in an acute collection, and may even be associated with the layering of blood products. An entity with an intermediate-density appearance on CT should not automatically be interpreted as a subacute/chronic hematoma, and the layering of blood products does not automatically indicate an acute-on-chronic hematoma. These concepts are very different from conventional teachings in adult neuroradiology, and awareness of them is exceedingly important (Fig. 6.4). An elderly patient with underlying brain-parenchymal atrophy may have an asymptomatic chronic hematoma. When there is bleeding into this chronic collection, there will be layering of blood products, which are felt to be acute-on-chronic blood products, and in adults this latter belief is usually correct. In children, however, the assumption might be that a volume of low-density material is a chronic hematoma that was previously present but asymptomatic. Given the relative paucity of extra space in the pediatric skull, however, this is not possible; a low-density portion of a collection would be symptomatic. Awareness of this is important because this finding is sometimes described as a mixed-age subdural hematoma suggestive of a hematoma related to NAT. Although the findings in such cases could be related to NAT, they are always likely to be acute. Similarly, patients may have a hematohygroma of intermediate density over one hemisphere and a hematoma overlying the other hemisphere; both of these collections could be acute collections, and should therefore be described as mixed-density subdural collections but not as mixed-age subdural collections.

Layering of blood products can also occur within an acute collection in a patient with impaired coagulation as the result of either an intrinsic coagulopathy or pharmacologic therapy. A subdural collection of low density in an anemic patient, such as a child with leukemia, may be an acute, life-threatening emergency. Even the presence of layering blood products may be due to impaired clotting in these patients, who may have thrombocytopenia. Therefore, especially in a patient with anemia or a coagulopathy, such as a leukemia patient, a collection should not be designated as chronic unless a prior study shows that the collection was previously present.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree