7 Kidney Ablation

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) exhibits unique epidemiologic and pathophysiologic characteristics compared with most other neoplasms. It is mass forming (not infiltrative), usually small at time of diagnosis (approximately 70% of newly diagnosed RCCs are <4 cm), and involves an organ that is duplicated and surrounded by retroperitoneal fat. Additionally, it is slow growing, with a reported doubling time of 500 to 600 days, the risk of metastatic disease is correlated to the size of the primary tumor and thus usually is a late-stage complication, and is easily detectable by current imaging modalities. These factors conspire to render most patients with RCC potentially curable. Because of the drive to preserve as much normal renal parenchyma as possible, the role of percutaneous ablation has been expanding; however, treatment selection is occasionally not straightforward.

♦ Current Treatment Options: Placing Ablation into Context

There are several choices for the treatment of organ-confined renal cancer, including percutaneous ablation, open ablation, open partial nephrectomy, open nephrectomy, laparoscopic nephrectomy, laparoscopic partial nephrectomy, and laparoscopic ablation. Total nephrectomy, whether open or laparoscopic, should be a choice of last resort. Nephron-sparing interventions are the current gold standard. Partial nephrectomy, when technically feasible, has been shown to have the same long-term efficacy as that of total nephrectomy, and this is the treatment most commonly selected. Whether to perform open or laparoscopic partial nephrectomy depends on tumor morphology and operator experience. Percutaneous ablation, building on laparoscopic or open ablation safety and efficacy data that are comparable to those of nephron-sparing surgical options, has carved an expanding niche. Initially reserved only for patients who were not surgical candidates, percutaneous ablation is a very attractive option for patients who wish to avoid surgery. This shift has been partly fueled by the ability of patients to use the Internet to better understand treatment options and by the fact that possible failure of percutaneous ablation does not obviate surgical options.

Radical nephrectomy should be a choice of necessity and selected only if a curative nephron-sparing treatment option is not available. This is usually the only treatment option for large, central renal masses in which adequate surgical margins cannot be obtained without sacrificing the main renal artery or vein. Given the faster recovery and fewer complications in experienced hands, laparoscopic nephron-sparing options are preferred. Those include laparoscopic partial resection and laparoscopic ablation. During the last few years, several authors published their experience with percutaneous ablation for RCC. Despite the lack of prospective randomized studies, the fact that these independent authors report near identical safety and efficacy rates corroborates the utility of percutaneous ablation. For lesions 4 cm or smaller, the reported efficacy hovers around 95% and the risk of significant complications around 6%.1 Even though these numbers compare favorably with the other nephron-sparing options, long-term data are still lacking.2,3 Precisely because RCC is a slow-growing tumor, 1- and 2-year data cannot be interpreted as conclusive, and therefore 5-year data are necessary. Nonetheless, a significant number of patients can benefit from percutaneous ablation.

♦ Patient Selection

Occasionally the treatment choice will be clear. For example, a large RCC in a healthy patient with normal kidney function and without high risk for metachronous occurrence should be removed surgically, preferably avoiding nephrectomy. At the other end of the clinical scenario spectrum, are patients who cannot or should not have surgery for their small RCC. Such patients include high-risk anesthesia/surgery patients, patients with solitary kidney predialysis patients, patients with bilateral tumors, and patients with syndromes that predispose them to metachronous RCC. These lesions generally should be treated with nephron-sparing interventions, including percutaneous ablation. Because of the emerging treatment options and the need to preserve renal function even in patients with two well-functioning kidneys, there is a large gray zone in between. This is further confounded by the fact that many patients drive their own treatment toward nonsurgical options, especially because a possible failure of percutaneous ablation does not exclude the treatment the patient would have had in the first place. Whatever the case may be, the decision on the most appropriate treatment option should be arrived at after consultations with specialists who cover the treatment spectrum, including urologists and interventional radiologists.

The health status of the patient is also important when planning a percutaneous ablation for RCC. Some patients are steered toward percutaneous ablation because of comorbid conditions. Ablation of large tumors in older patients with preexisting cardiopulmonary disease presents a special group that should be approached carefully. Seemingly minor complications can have a more pronounced effect on such patients. Additionally, “cryoshock,” a rare complication of cryoablation, can be seen more frequently in this group. It may be prudent to stage ablation treatment in such patients in two or even three sessions.

♦ Tumor Selection

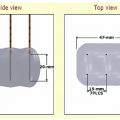

Two factors are the main determinants of the technical feasibility of percutaneous ablation: tumor size and tumor location. Current data appear to support the reported high efficacy and low complication rates of percutaneous ablation, for RCCs that are 4 cm or smaller. Some authors have published very good results in treating lesions larger than that; however, the small number of patients that fall in this category does not allow for definitive conclusions. Tumor location can be a mul-tifaceted challenge. The lesion can be very central, abutting the main renal vessels or collecting system. It can be anterior to the kidney, not allowing for an access window, or it can be adjacent to a vital organ. The operator’s experience is very important in this case. For example, a seemingly untreatable lesion because of location may be successfully approached if the adjacent bowel is pushed away with saline injection. Or, a lesion abutting the collecting system can be ablated safely after the preventive placement of a nephroureteral stent. The following section details these scenarios.

♦ Complications and Anatomic Considerations

Transpulmonary Approach

Occasionally the tumor resides in the upper pole of the kidney, making a transpulmonary approach possible or even necessary. This is not a contraindication to treatment. Figures 7.1 and 7.2 describe such cases. Angling the computed tomography (CT) gantry caudally or using caudal access angle on ultrasound guidance could help avoid crossing the pleura. When a transpulmonary approach is unavoidable, it may result in complications, including pneumothorax or hemothorax. The operator should be capable of recognizing and treating these promptly. If the diaphragm is abutting the target lesion, air dissection or hydrodissection should be used to prevent injury. Though rare, diaphragmatic rupture requiring surgery has been reported, and is more likely to be seen with radiofrequency ablation (RFA) than with cryoablation.

Nerve Injury

There are two nerves that are at risk of injury during percutaneous renal ablation ( Fig. 7.3 ), the first being the lower intercostal nerves that run along the undersurface of each rib. Injury to one of these nerves can cause both motor and sensory deficits. Motor deficits usually go unnoticed because the related muscles (external intercostal muscles, obliquus externus abdominis, transversus abdominis, and obliquus internus) have cross-functionality with other muscles, or the deficit is small. On the other hand, sensory deficits are frequently encountered and include paresthesias and pain along the dermatome. The second is the genitofemoral nerve that runs craniocaudally along the anterolateral surface of the psoas muscle. This nerve is at risk of injury when peripheral lesions on the medial surface of the kidney are targeted. Injury to this nerve results in sensory findings along the inner thigh including pain, numbness, and paresthesias. There are reports asserting that cryoablation is more forgiving than heat ablation, especially related to nerve injury. Indeed, permanent nerve injury after cryoablation is rare, and most patients tend to recover within weeks of nerve injury.

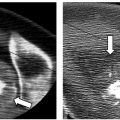

Collecting System Injury

Ablation of central lesions that abut portions of the collecting system may result in segmental or complete obstruction ( Fig. 7.4 ). Calyceal injury may result in stricture and subsequent obstruction of said calyx, which, however, is unlikely to alter renal function. Another possible consequence of collecting system injury is hematuria. Central lesions are at higher risk; however, in most cases hematuria is not clinically significant and is self-limiting, resolving over the following 2 to 4 days. If the patient is able to void and vitals are stable, no intervention or further hospitalization is necessary. Rarely hematuria can be clinically significant, and results in hematocrit drop or even collecting system thrombus and obstruction ( Fig. 7.5 ). Nevertheless, it may result in a urinoma as the system attempts to decompress, which could be further complicated by infection. Anterior, lower pole lesions represent a special case because of their proximity to the ureter. The ureter drapes along the anterior portion of the lower pole of the kidney. Inadvertent nontarget ablation of the ureter may result in complete obstruction, severe hydronephrosis, and possible kidney loss. Postablation ureteral strictures are notoriously difficult to treat, and the placement of a nephroureteral catheter through the stricture may not be possible. The preablation placement of a nephroureteral stent may alleviate this complication. The internal nephroureteral stent is placed just prior to ablation and kept long enough to allow for healing of the injured ureter (at least 4 to 6 weeks).

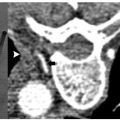

Adjacent Organs

Various organs may be at risk for nontarget ablation. They include the liver, spleen, adrenal, pancreas, and more, frequently, the bowel ( Fig. 7.6 ). Partial nontarget ablation of the liver or spleen is mostly inconsequential, and should not be a contraindication to performing the procedure. Care should be exercised to avoid unnecessarily puncturing these organs, however, because of the risk of hemorrhage. The intentional transhepatic approach has been described and sometimes may be necessary for anterior lesions in the right kidney ( Fig. 7.7 ). RFA offers the added advantage of cauterizing the tract, thus mitigating potential hemorrhage, as opposed to the larger caliber cryoprobes. Nontarget ablation of the bowel ( Fig. 7.8 ) or pancreas, however, may result in serious or life-threatening complications. Certain maneuvers (described later in this chapter) could mitigate this risk and allow the procedure to go forward. However, the inability to avoid ablating the pancreas or bowel should be a contraindication to the procedure. Targeting upper pole exophytic lesions may result in partial or total ablation of one of the adrenal glands. Because ablation of RCC is considered a curative procedure, as long as the patient has two functioning adrenal glands, the risk of partial or even total ablation of one should not be a contraindication to the procedure. Rarely, intentional adrenal ablation may be necessary ( Fig. 7.9 ) as the RCC involves the adrenal gland, by direct extension or as a solitary metastasis. Ablation of a small-enough tumor despite adrenal extension or involvement (stage 3a, N0,M0) ( Table 7.1 ) can still be a curative intervention as long as the rest of the tumor is confined within Gerota’s fascia. The operator, however, should protect against arrhythmia or a hypertensive crisis as a result of catecholamine release during adrenal injury. Beta- as well as alpha-blockade may be required prior to ablation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree