JUVENILE IDIOPATHIC ARTHRITIS

Seropositive and Connective Tissue Arthropathies

Seronegative Spondyloarthropathy

CRYSTAL-INDUCED ARTHRITIDES

Gouty Arthritis

Calcium Pyrophosphate Dihydrate Crystals

Hemochromatosis

Hydroxyapatite Deposition Disease

DEGENERATIVE ARTHRITIDES

Degenerative Joint Disease

Intervertebral Disc Herniation

Spinal Stenosis

Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis

Neuropathic Arthropathy

Arthritis is the most common self-reported chronic condition among whites, the second most common among Native Americans and Hispanics, the third most common among blacks, and the fourth most common condition among Asians. For all groups, arthritis is a more prevalent chronic condition than heart disease, hearing impairments, chronic bronchitis, asthma, and diabetes. 106 Arthritis and its related conditions have a significant impact on activities of daily living, such as housekeeping, sleeping, driving, and working. Early recognition and appropriate management of arthritis are important to limit its progression and related disabilities.

IMAGING

Plain film radiography is still the most widely used and useful imaging modality for diagnosing, differentiating, and evaluating the various arthropathies. 552 Despite some limitations (e.g., insensitivity to very early joint changes), it is difficult to imagine proceeding to more advanced imaging techniques without first evaluating the patient with plain film radiography. It adequately demonstrates bone erosions, osteophytes, alterations of joint space, and misalignment. Plain film radiographs yield a relatively low dose of radiation, are inexpensive, and are readily and rapidly obtained. These factors make it perfect for baseline and serial studies that can be used to provide important information about the progression of the disease and the effectiveness of any treatment regimen. The addition of intraarticular injections of air or contrast allows limited demonstrations of the internal components of joints.

Advanced imaging modalities are being used in conjunction with plain film radiography because they may provide early detection of subtle findings such as synovitis, periarticular osteoporosis, and early erosions, when plain films are negative or inconclusive. Advanced imaging also is useful in evaluating joints with complex anatomy such as the sacroiliac (SI) articulations, which may be difficult to evaluate by the use of plain film. Computed tomography (CT) provides excellent anatomic detail and images in an axial plane. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is used to evaluate the cartilaginous and ligamentous joint structures and marrow of the adjacent bone. Scintigraphy provides a useful method of gathering functional information to aid in morphologic assessments provided by other imaging modalities. Ultrasonography has the capability to define joint effusions and identify edematous connective tissues.

CLASSIFICATION

In general, arthritis can be grouped into three major categories: inflammatory (rheumatoid), crystal-induced (gout), and degenerative (osteoarthritis). Inflammatory arthritides are subdivided into rheumatoid arthritis (and related diseases) and connective tissue disorders. They also can be subdivided into rheumatoid types (seropositive) and rheumatoid variants (seronegative) based on the likelihood of the serologic presence or absence of the rheumatoid factor, as established by the latex fixation test.

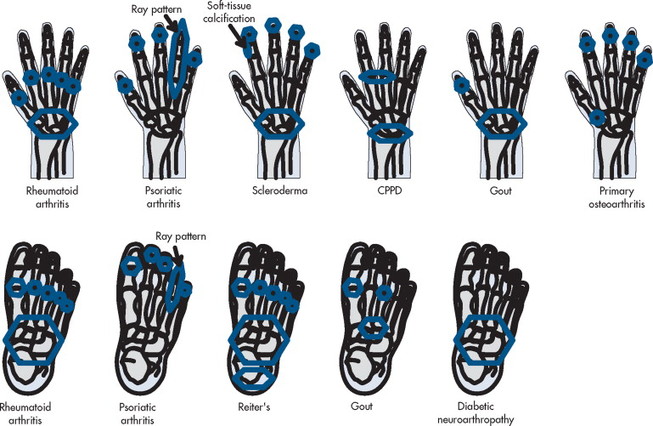

Arthritis may be monoarticular or polyarticular. All types of arthritis may be monoarticular early in their pathologic course. Joint abnormalities that are caused by trauma or infections usually remain monoarticular. Arthritides are differentiated on the basis of clinical data and imaging studies (Table 9-1 and Fig. 9-1). The most useful information about them comes from plain film radiographs coupled with clinical data that relate to skeletal distribution, patient age, patient gender, joint swelling, joint stiffness, joint range of motion, symptom response to physical activity, and laboratory tests (e.g., erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR], antinuclear antibodies [ANAs], human leukocyte antigen [HLA] typing).

| ANA, Antinuclear antibodies; AS, ankylosing spondylitis; CPK, creatinine phosphokinase; CPPD, calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; HADD, hydroxyapatite deposition disease; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; JIA, juvenile idiopathic arthritis; LBP, low back pain; MCP, metacarpophalangeal; MTP, metatarsophalangeal; PIP, proximal interphalangeal joint; RF, rheumatoid factor; SI, sacroiliac. | ||||||||

| Arthritismode | F:M ratio | Age of onset | Target joints | Distribution | Radiographic features | Clinical features | Lab | Extraarticular manifestations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rheumatoidinflammatory | 3:1 | 40–70 | MTP, MCP, PIP, knees, hips, cervical spine | Bilateral, symmetric | Capsular swelling, symmetric joint space narrowing, juxtaarticular osteoporosis, marginal erosions; joint deformity | Morning stiffness, joint swelling | +RF (IgM), ↑ESR, 10%–50% ANA, ↑C-reactive (CR) protein | Rheumatoid subcutaneous nodules, pulmonary, cardiovascular |

| JIA/inflammatory | 3.5:1 | <16 | Knees; ankles; elbows; wrists; cervical spine | Bilateral, symmetric if polyarticular | Capsular swelling, symmetric joint space narrowing, juxtaarticular osteoporosis, marginal erosions, ankylosis, growth abnormalities, periostitis | Varies with subtype: systemic-fever, adenopathy; arthralgia; rash; limp | ± RF, HLA-B27 and ANA depending on subtype; ↑ESR and C-R protein; systemic = leukocytosis | Varies with subtype; hepatosplenomegaly subcutaneous nodules; iridocyclitis |

| SLE/inflammatory | 9:1 | 30–50 | MCP; PIP of the hands primarily | Bilateral, symmetric | Nonerosive, reversible, joint deformities; osteonecrosis as possible complication | Arthralgia; butterfly rash; constitutional signs and symptoms | ANA (98%); anti–DNA antibodies; LE cells (70%–85%); RF (20%–35%); ↑ESR and C-R protein | Rash; renal disease; interstitial lung disease |

| Scleroderma/inflammatory | 8:1 | 35–65 | Distal tufts; DIP; PIP of the hands primarily | Bilateral, symmetric or asymmetric | Acroosteolysis, erosions, subcutaneous calcifications | Raynaud phenomenon; skin fibrosis; arthralgia of hands; telangiectasia | ANA in 60%; +RF (30%); ↑ESR | Skin fibrosis; renal fibrosis; GI fibrosis; interstitial lung disease; pericarditis |

| Polymyositis/dermatomyositis/inflammatory | 2:1 | 40–60 | Large muscles of the proximal appendicular skeleton; DIP, PIP, and MCPs | Bilateral, symmetric muscle involvement | Muscle edema; subcutaneous, intermuscular, and periarticular calcifications; transient osteopenia, soft-tissue swelling | Muscle weakness and atrophy; rash; arthralgia of hands, wrists, and knees | ↑CPK; muscle biopsy = inflammation and degeneration | Interstitial lung disease; pericarditis |

| AS/inflammatory | 1:10 | 15–35 | SI; spine: vertebral bodies and apophyseal articulations; hip; shoulder | Bilateral, symmetric | Erosions; periostitis; ankylosis; thin, marginal syndesmophytes | LBP and stiffness; limited chest expansion | +HLA-B27 (90%); − RF, ↑ESR, and C-R protein | Interstitial fibrosis; aortic insufficiency; iritis |

| Enteropathic/inflammatory | Varies with underlying bowel disorder | Varies | SI; spine; knee | Symmetric in axial skeleton; asymmetric in extremities | Mimics AS in the axial skeleton; nonerosive in the extremities | LBP and stiffness; IBD | +HLA-B27; − RF; ↑ESR | Underlying bowel disorder |

| Psoriatic/inflammatory | 1:1 | 30–50 | Predilection for upper extremity; DIP and PIP; SI; spine | Bilateral, symmetric, or asymmetric in SI joints; asymmetric in extremities | Sausage digit; marginal or central erosions with periostitis; early joint space widening with eventual narrowing; bulky, nonmarginal syndesmophytes; SI erosions and ankylosis | Psoriasis; nail changes (thickening, pitting, discoloration); LBP | +HLA-B27; − RF; ↑ESR | Psoriatic skin and nail changes |

| Reiter’s/inflammatory | 1:5 | 15–35 | Predilection for lower extremity; MTP; calcaneus; SI; spine | Asymmetric in foot; bilateral, symmetric, or asymmetric in SI joints | Mimics psoriatic in the spine and extremities; calcaneal enthesopathy | LBP; heel pain, urethritis; conjunctivitis | Leukocytosis; ↑ESR; HLA-B27 (75%); − RF | Pulmonary fibrosis; urethritis; conjunctivitis |

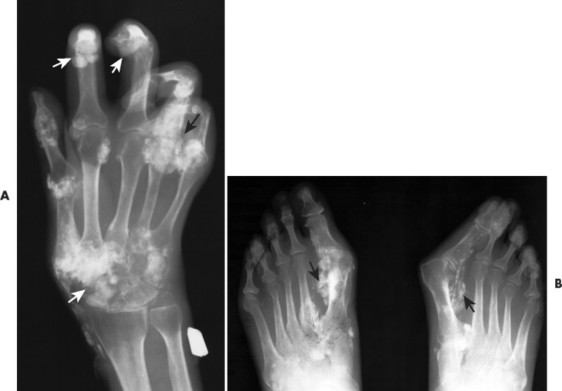

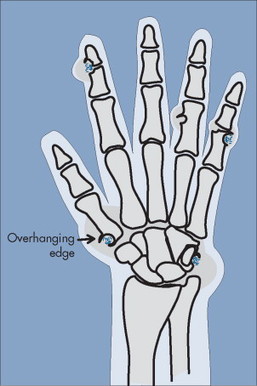

| Gout/crystal deposition | 1:20 | 40–50 | MTP of first digit; other MTPs, DIP, midfoot, ankle, DIPs of hand | Asymmetric; often monoarticular | Soft-tissue nodules (tophi) with calcification; paraarticular erosions; overhanging edge; preserved joint space; lack of osteopenia | Red, hot, swollen joint; usually monoarticular | Hyperuricemia; sodium urate crystals in synovial fluid | Tophus in bursa or helix of the ear |

| CPPD/crystal deposition | Varies with site of involvement | Varies; increases with age | Knee; wrist; hip; MCP | Often bilateral, asymmetric | Chondrocalcinosis; DJD–like changes; subchondral cysts | Varies from asymptomatic to acute goutlike pain. | Calcium pyrophosphate crystals in synovial fluid | None |

| HADDcrystal deposition | 1:1 | 40–70 | Shoulder | Asymmetric; usually monoarticular | Cloudlike periarticular calcification | Varies from asymptomatic to acute joint pain | Hydroxyapatite crystals by electron microscopy | None |

|

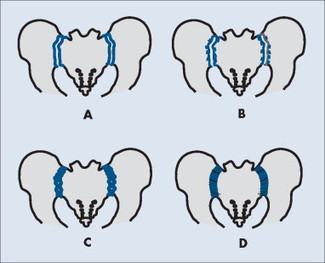

| FIG. 9-1 Distribution of selected joint diseases. |

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Adult Rheumatoid Arthritis

BACKGROUND

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an autoimmune disorder, and the most common chronic inflammatory arthritide, affecting approximately 1% of the general population and 2% of the population over 60 years old. 243,607,610 However, studies indicate that the incidence may be on a decline in certain populations. 155,289,303,304,503 The disease primarily affects the synovial lined joints and is frequently associated with a variety of extraarticular manifestations. RA is characterized by an inflammatory, hyperplastic synovitis (pannus), resulting in cartilage and bone destruction and consequent loss of function. Although it is known that genetic and immunologic factors play a role in its pathogenesis, the underlying etiology remains uncertain. 316,537 Proposed etiologic theories revolve around a combination of genetic susceptibility, hormonal changes or imbalances (e.g., pregnancy), and environmental or biologic triggers or risk factors (e.g., smoking, obesity). 30,129,338,679 The T cell is involved in initiating and possibly propagating the chronic inflammatory disease process. Competing theories hold that the T cell initiates the disease process, but the chronic inflammation is self-perpetuated via macrophages and fibroblasts independent of the T cell.

Joint involvement typically is bilateral and symmetric, involving the peripheral and axial skeleton, with the small joints of the hands and feet, the wrists, knees, elbows, hips, and shoulders particularly affected. 89 Changes in SI articulations are relatively infrequent. Although the peak occurrence of disease onset has previously been reported as 20 to 50 years of age, recent trends indicate an increased age of onset as 40 to 70 years old, with the peak occurrence at age 58. 155,303 Women are affected more often than men, and although some studies have shown a ratio as high as 7:1, it is generally accepted that women are affected two to three times more frequently than men. 63,129,406,610 If the disease onset occurs at a more advanced age (>60 years), this ratio approaches 1:1. 488,658

IMAGING FINDINGS

Plain film radiography is an inexpensive tool and may be used by practitioners on a frequent basis in clinical practice to support clinical and laboratory findings consistent with a diagnosis of RA, aid in eliminating possible differential diagnoses, and follow the progression of RA and the effectiveness of its treatment. 568,590 Ultrasonography and MRI are superior in detecting synovitis, and many of the initial subtle joint changes are visible much earlier with MRI; however, it is not used routinely because of its high cost. Therefore this section focuses on plain film findings. 123,165,513

RA is classically symmetric and may involve any synovial joint. The general radiographic findings reflect the underlying pathologic change of chronic synovial joint inflammation with associated hyperemia, edema, and pannus formation. The first feature, which is usually the sole finding for the first few months, is fusiform periarticular soft-tissue swelling arising from capsular distention caused by excessive fluid accumulation seen clinically. Increased blood flow to the synovium leads to a second early radiographic finding of juxtaarticular osteoporosis, which later becomes more generalized because of patient inactivity. 298,380

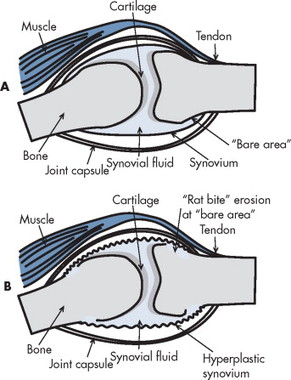

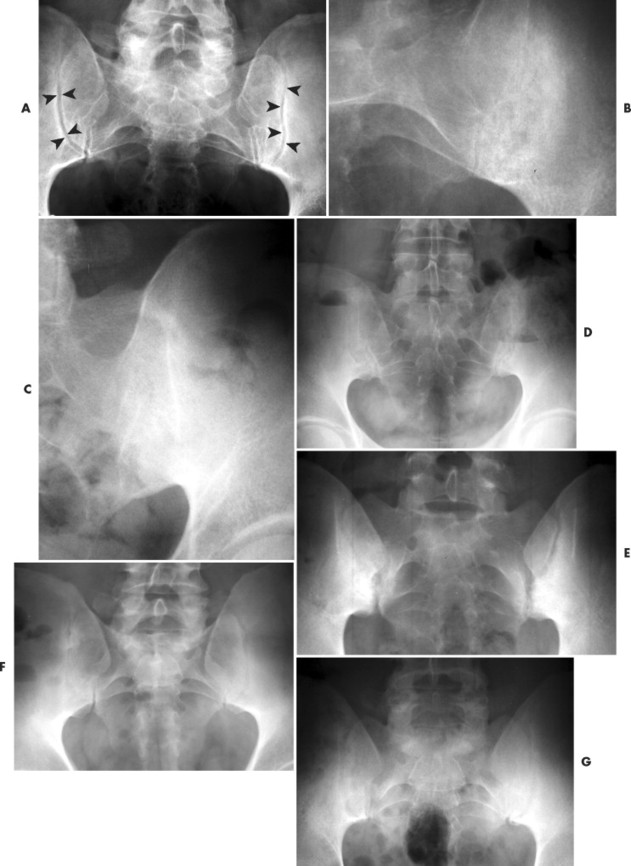

Joint spaces eventually narrow uniformly as the cartilage is destroyed by the enzymatic nature of pannus. Osseous erosions usually become apparent within the first 2 years of the disease, 84,212,512 first occurring at the unprotected bone margins or “bare areas” (Fig. 9-2) in which the pannus has direct osseous contact, and later involving the subchondral bone. The appearance of alternating pattern of erosions and normal cortical bone has been termed a “dot dash” appearance. Multiple, nonmarginated subchondral cysts or geodes typically develop and may communicate with the synovium. 400,652

|

| FIG. 9-2 A and B, Inflamed, hyperplastic synovitis of rheumatoid arthritis, known as pannus, classically demonstrates early osseous erosions at the margins of the synovial joint that are unprotected by articular cartilage (“bare area”). |

Later stages of the disease give rise to joint deformities resulting from tendon and ligament laxity, ruptures, and contractures. During periods of prolonged remission, radiographic signs of secondary osteoarthritis (OA) may develop, fibrous ankylosis may occur, and bony ankylosis may develop on rare occasions.

Hands and feet.

The earliest clinical and radiographic changes are characteristically found in the hands and feet. 652 Although evaluation methods of RA focus on radiographs of the hands, the feet appear to show osseous erosions first and to a greater extent. 84,272,284,512,651 The initial involvement is of the head of the fifth metatarsal, with erosion and narrowing of the fifth metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint.

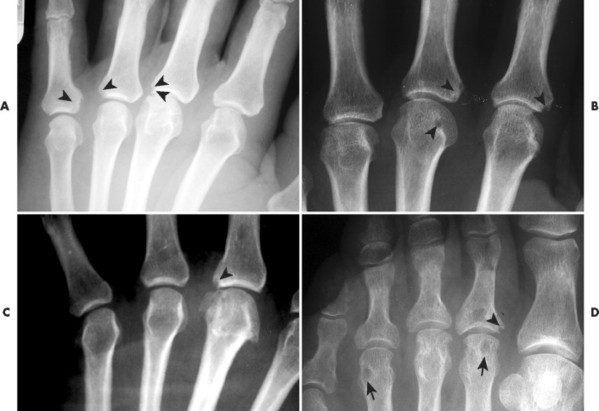

The classic joint distribution of RA in the hands is bilateral and symmetric involvement of the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) and proximal interphalangeal joint (PIP) articulations. Some or all of the general radiographic features may be seen, with the earliest osseous erosions occurring at the MCP joints of the second and third digits of the dominant hand, 357 and at the radial aspect of the metacarpal heads (Fig. 9-3). Norgaard and Brewerton’s views may aid in visualization of these early joint erosions, although it is difficult to duplicate the exact positioning on serial radiography. 652 In Norgaard’s view, the hands are 45 degrees supine, with the fingers straight, 461 and in Brewerton’s view (ballcatcher’s view), the MCP joints are flexed at 65 degrees. 79

|

| FIG. 9-3 Small marginal “rat bite” erosions (arrowheads) occur in the region of the joint that is unprotected by overlying articular cartilage, known as the bare area. A to C, Small marginal erosions of the metacarpophalangeal and, D, metatarsophalangeal joints are hallmark features of rheumatoid arthritis, noted here in three patients. Subchondral cysts also are noted in case D (arrow). |

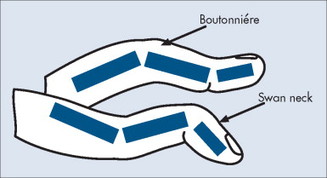

Characteristic joint deformities include the swan neck deformity, boutonnière deformity, ulnar deviation of the fingers (doigts en coup de vent), and the hitchhiker’s or Z-shaped deformity of thumb. The swan neck deformity results from hyperextension of the PIP and hyperflexion of the distal interphalangeal joint (DIP) (FIG. 9-4FIG. 9-5FIG. 9-6 and FIG. 9-7), whereas the boutonnière deformity represents the opposite configuration of hyperflexion of the PIP and hyperextension of the DIP. The hitchhiker’s thumb is secondary to MCP flexion and interphalangeal (IP) extension (see Fig. 9-5). Ulnar deviation at the MCPs is called ulnar drift; when combined with radial deviation in the radiocarpal articulations it results in a “zigzag” deformity (see Fig. 9-5). Loosening or disruption of the distal attachment of the extensor tendon to the terminal phalanx leads to a “mallet” finger.

|

| FIG. 9-4 Rheumatoid arthritis. The ulnar deviation of the fingers, especially prominent at the fifth digit of the right hand, and Z-deformity of the left thumb are the most obvious features of rheumatoid arthritis in this patient. (Courtesy Steven P. Brownstein, MD, Springfield, NJ.) |

|

| FIG. 9-5 Ulnar deviations of the fingers and advanced arthropathy of the metacarpocarpal joints and wrist are consistent with rheumatoid arthritis. (Courtesy Steven P. Brownstein, MD, Springfield, NJ.) |

|

| FIG. 9-6 Rheumatoid arthritis characteristically manifests with interphalangeal joint misalignments. The misalignments express either swan neck deformity (flexion of distal and extension of the proximal interphalangeal joints) or boutonnière deformity (extension of the distal and flexion of the proximal interphalangeal joints). |

|

| FIG. 9-7 Rheumatoid arthritis with ulnar deviation of the fingers, metacarpal joint involvement, and advanced destruction of the wrist. (Courtesy Gary Longmuir, Phoenix, AZ.) |

Changes in the feet tend to parallel those of the hands, with the MTP articulations commonly being affected first and other deformities, including lateral or fibular deviation at the MTPs of the first through fourth digits, flexion of the DIPs (hammer or claw toes), and extension of the MTPs eventually developing (FIG. 9-8FIG. 9-9FIG. 9-10 and FIG. 9-11). Pathologic changes in the deep transverse tendons may lead to spreading of the metatarsals or forefoot. Pathologic changes in supporting ligaments also may lead to hallux valgus. Retrocalcaneal bursitis, plantar fasciitis, Achilles tendonitis, or Achilles tendon rupture may occur in the heel.

|

| FIG. 9-8 Rheumatoid arthritis presenting with subchondral cysts (arrowheads) and reduction of the first metatarsophalangeal joint bilaterally (arrows). |

|

| FIG. 9-9 Rheumatoid arthritis of the foot with advanced changes of the fibular misalignment of the toes, osteopenia (more pronounced in the periarticular regions), reduced joint spaces, and generalized atrophy of the bones. |

|

| FIG. 9-10 Fifty-year-old male rheumatoid patient demonstrating marked symmetric and bilateral fibular deviation of the toes. (Fibular deviation with posterior subluxation of the metatarsophalangeal joints is termed Lanois deformity.) |

|

| FIG. 9-11 Rheumatoid arthritis manifests with bone reapportion. In this 64-year-old woman, rheumatoid arthritis has caused a tapered appearance of the distal metatarsals. |

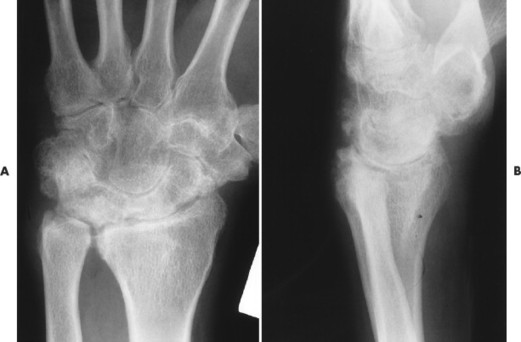

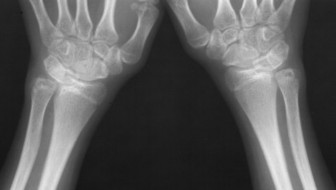

Wrist.

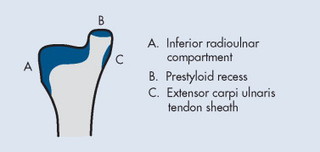

Pancompartmental involvement typically is in the wrist, with the earliest erosions usually involving the radial and ulnar styloid processes; distal radioulnar and radiocarpal joints; and waist of the scaphoid, triquetrum, and pisiform (FIG. 9-12FIG. 9-13FIG. 9-14FIG. 9-15 and FIG. 9-16). 357 Ligamentous instability results in patterns that parallel posttraumatic lesions, such as scapholunate dissociation, distal radioulnar dissociation, and dorsiflexion or volar flexion instability.

|

| FIG. 9-12 Rheumatoid arthritis presenting with wrist and metacarpal destruction with slight ulnar deviation of the fingers. (Courtesy Steven P. Brownstein, MD, Springfield, NJ.) |

|

| FIG. 9-13 Rheumatoid arthritis presenting with bilateral, symmetric destructive changes of the intercarpal joints of the wrist. |

|

| FIG. 9-14 Erosions of the ulnar styloid may manifest in each of the areas that have adjacent synovial tissue: radiocarpal joint, prestyloid recess, and extensor carpi ulnaris. |

|

| FIG. 9-15 A and B, Erosions of the styloid process in two patients (arrows). |

|

| FIG. 9-16 A and B, Rheumatoid arthritis in the wrist. Inflammation is most notable in the proximal row of carpals, radiocarpal compartment, and distal ulna. Mild osseous proliferation is noted, suggesting clinical quiescence. |

Elbows.

Joint effusion is recognized by a positive fat pad sign. Osseous erosions may be noted at each of the articulating surfaces.

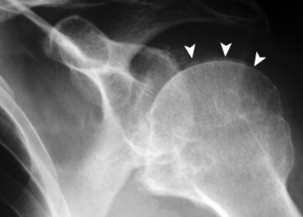

Shoulders.

The glenohumeral and acromioclavicular (AC) joints may be affected. Resorption of the distal clavicle, in addition to erosions at the coracoclavicular ligament insertion on the undersurface of the clavicle, is not uncommon. Erosion may be observed on the medial aspect of the humeral neck as it abuts the glenoid process from elevation of the humerus, which is caused by a rotator cuff tear secondary to a chronically inflamed supraspinatus tendon. The acromiohumeral distance narrows with progressive elevation of the humeral head, and sclerosis and cyst formation are noted on the adjacent portions of the humeral head and acromion process.

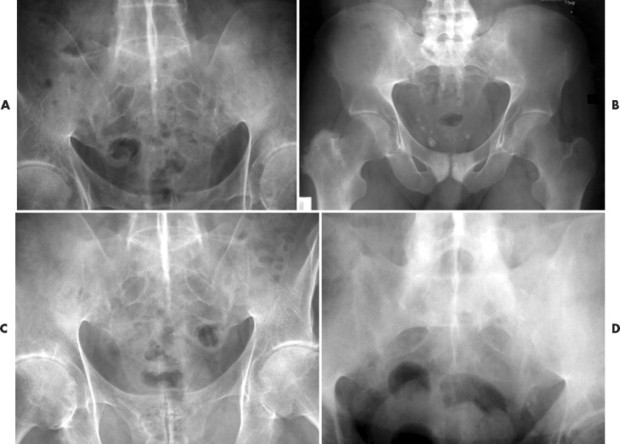

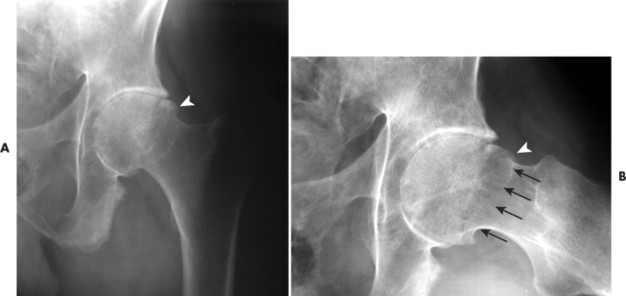

Hips.

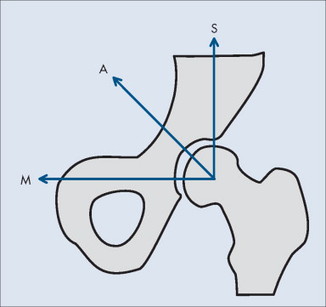

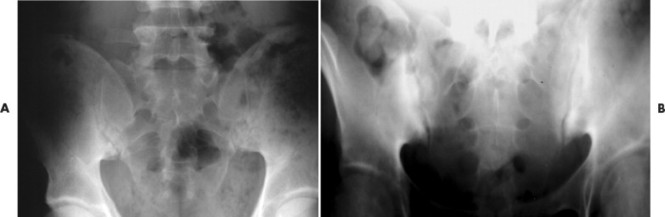

Abnormalities of the hips generally are bilateral and symmetric. Axial migration of the femoral head and bilateral acetabular protrusion are common findings that accompany the other general features of concentric joint space narrowing, erosions, and subchondral cysts associated with RA (Figs. 9-17 and 9-18). 134 There is an absence of sclerosis and osteophyte formation unless secondary OA has developed.

|

| FIG. 9-17 The iliofemoral joint is divided into an, M, medial; A, axial; and, S, superior component. The inflammatory arthritides, inclusive of rheumatoid arthritis, tend to decreased all of these spaces symmetrically, whereas degenerative joint disease reduces the superior, weight-bearing aspect of the joint and increases the medial joint space. |

|

| FIG. 9-18 Early rheumatoid arthritis of the hip shown by concentric loss of joint space, small erosions of the femoral head and acetabulum, and osteopenia. Note the lack of osteophytosis and eburnation. |

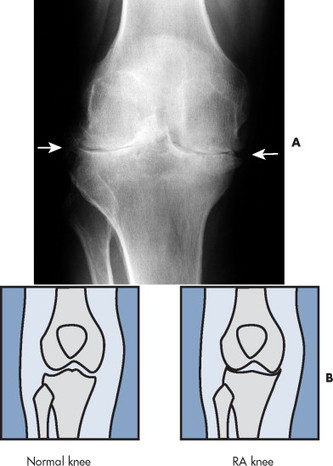

Knees.

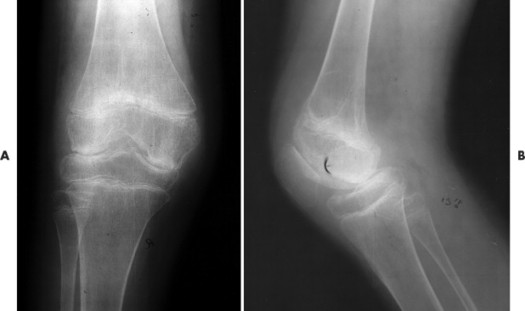

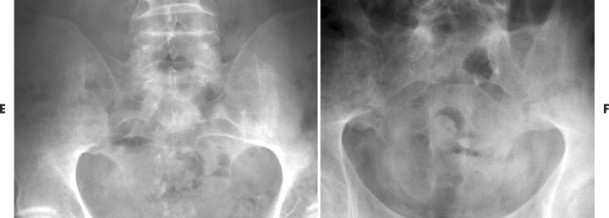

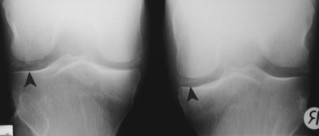

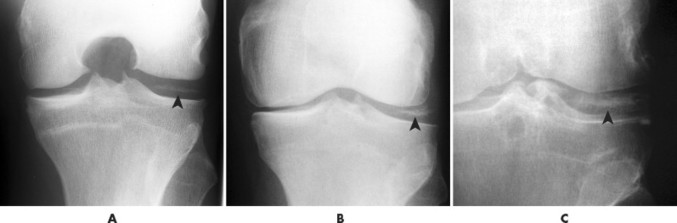

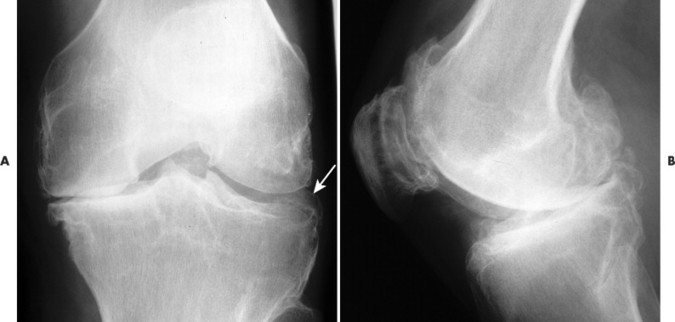

Tricompartmental involvement that includes the general features of joint space narrowing and osseous erosions is typical (Figs. 9-19 and 9-20). A genu valgus deformity is more likely to develop than a varus joint deformity (Fig. 9-21). Soft-tissue swelling may be present in the form of suprapatellar effusion or a large popliteal (or Baker’s) cyst. Subchondral sclerosis and osteophytes may be noted with the development of secondary osteoarthritis.

|

| FIG. 9-19 A and B, Rheumatoid arthritis noted by symmetric reduction of both the medial and lateral femorotibial joint spaces (arrows). |

|

| FIG. 9-20 Rheumatoid arthritis. In this case, rheumatoid manifests with osteoporosis and symmetric loss of the femorotibial joint spaces. The symmetric loss of joint space noted in these cases is contrary to what is expected with degenerative joint disease. Degeneration presents with asymmetric loss of joint space (more advanced in the medial femorotibial compartment) and osteophytes. |

|

| FIG. 9-21 Genu valgus deformity is noted in this 57-year-old woman. The film is annotated in preparation for surgical placement of a prosthesis. |

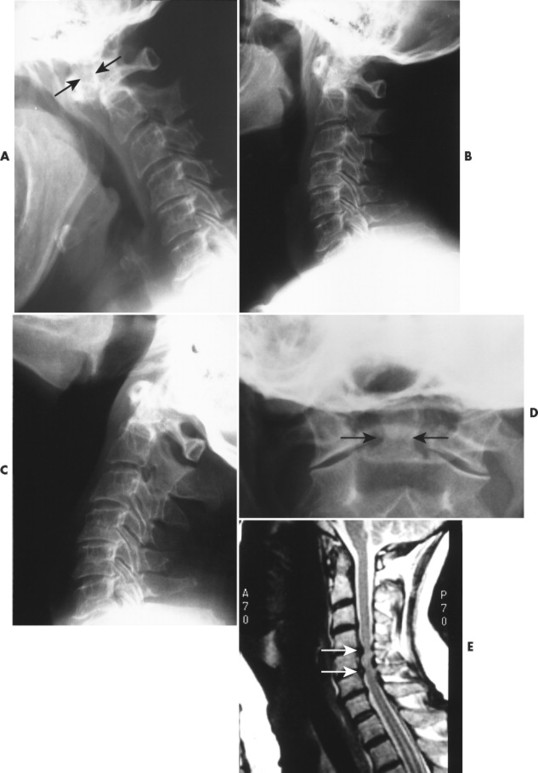

Cervical spine.

RA involvement is rare in other regions of the axial skeleton but affects the cervical spine in more than half the patients within the first 10 years of disease onset, 531,652 with a preference for the apophyseal and atlantoaxial joints. The more chronic the disease, the greater is the likelihood of cervical involvement. 466 Radiographs of the cervical spine are a prudent consideration in all patients with RA regardless of symptoms, because many patients are asymptomatic despite cervical involvement. 117 These should include lateral views with the patient in flexion and extension.

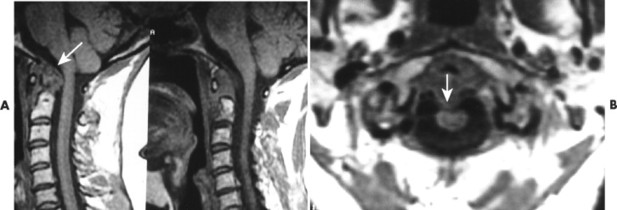

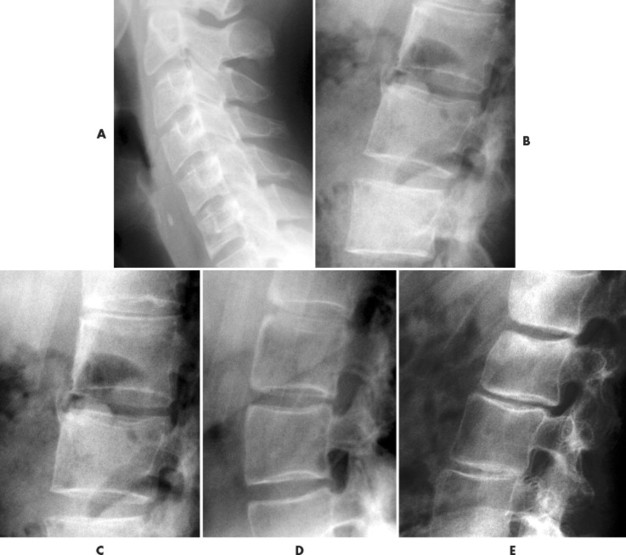

Atlantoaxial subluxation or instability is the most common radiographic abnormality encountered in the cervical spine, with the prevalence varying from 19% to 70% depending on the patient selection and radiographic examination (Fig. 9-22). 311 Movement may occur in several directions (listed in order of decreasing frequency): anterior (most frequent, 9.5% to 36%), lateral, vertical, or posterior. 55,107 Movement is usually the result of odontoid erosions or transverse ligament laxity, although the alar and apical ligaments also may be involved.

|

| FIG. 9-22 Anterior atlantoaxial subluxation. A, Lateral radiographs of the cervical spine in flexion; B, neutral; and, C, extension positions revealing an atlantoaxial subluxation that is most notable on the flexion radiograph. Note the wide gap between the posterior surface of the anterior arch of the atlas and anterior aspect of the odontoid (arrows). D, The anteroposterior open mouth radiograph of the same patient reveals rheumatoid erosions at the base of the odontoid process (arrows). The lateral atlantoaxial joints appear unaffected. E, Sagittal T2-weighted magnetic resonance image (MRI) of same patient revealing marrow changes of the odontoid process, synovial inflammation, and multiple subaxial subluxations in the middle and lower regions of the cervical spine with disc protrusions (arrows) and resulting cord compression. Instability resulting from rheumatoid pannus is a concern for neck movement, including chiropractic adjustments, neck movement with spinal surgery, or placement of an endotracheal tube related to emergency medicine. If instability is suspected, flexion-extension studies, computed tomography, or MRI are warranted for further investigation. |

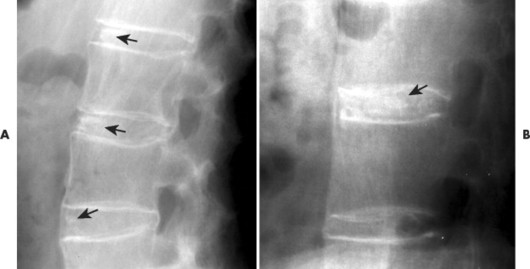

The degree of anterior subluxation shown on conventional radiography correlates poorly with neurologic signs and the presence of cord compression, which is in part a result of the unknown thickness of the synovial pannus not visible on plain films. 55,542 The standard method for determining anterior atlantoaxial subluxation has been an anterior atlantodental interval* (ADI) of greater than 3 mm, but it has been shown that a posterior atlantodental interval† (PADI) of 14 mm or less may be a more reliable predictor for neural compression and necessitate an MRI for evaluation of true cord space (Fig. 9-23). 55

*The ADI is the distance between the posteroinferior aspect of the anterior arch of the atlas and the most anterior point of the odontoid process. Measurements of greater than 3 cm are considered abnormal. The measurement should be obtained from a lateral flexion radiograph.

†The PADI is measured from the posterior wall of the dens to the anterior aspect of the C1 lamina.

|

| FIG. 9-23 A, Sagittal T1-weighted gradient echo and, B, axial gradient echo magnetic resonance images revealing prominent synovial inflammation (pannus) in the posterior median atlantoaxial joint (arrow) with apparent destruction of the dens and mild compression of the spinal cord (arrow). |

Vertical atlantoaxial subluxation also is known as cranial settling, atlantoaxial impaction, and pseudobasilar invagination. Superior migration of the odontoid occurs with erosion of the occiput-C1 and C1-2 articulations, resulting in approximation of the dens and brainstem, which can lead to direct compression or cause neurologic damage by excessive kyphosis. 92,542 McGregor’s line may be used to assess superior migration, or the Sakaguchi-Kauppi method may be used, which was developed for screening purposes and evaluating the position of C1 in relation to C2. 312

Subaxial subluxations may occur in 10% to 20% of patients and often are at multiple levels. C3-4 and C4-5 are the most common areas of involvement, producing a “stepladder” or “doorstep” deformity and associated kyphosis on the lateral radiograph. 478 Although these are less common than upper cervical spine subluxations, they are potentially more important neurologically because of the smaller spinal canal dimensions. 55,107 A canal measurement may be taken from the lateral radiograph in a similar way that the PADI is taken. If the subaxial canal diameter measures less than 14 mm, MRI is advised. 55

Disc height narrowing, mild subchondral sclerosis, and erosions of the vertebral endplates, facet joints, and spinous processes are other less severe signs of rheumatoid involvement. These signs often are subtle and difficult to diagnose on plain film radiographs.

Lungs.

Lung involvement is common, although not always clinically significant. Pleural involvement (e.g., pleurisy, pleural effusion) is the most common lung manifestation and usually is asymptomatic. 13 Other pulmonary manifestations include pulmonary fibrosis or honeycombing, constrictive bronchiolitis, bronchiectasis, pulmonary nodules, and subpleural micronodules (Fig. 9-24). High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) is useful for this avenue of investigation. These findings have been observed on CT in patients with symptoms, and those asymptomatic patients with no abnormalities noted on chest plain film. 546 Caplan syndrome describes inflammation and scarring of pulmonary tissue in people with RA who have exposure to coal dust.

|

| FIG. 9-24 Radiodense linear shadows most prominent in the lower lung fields as a feature of pulmonary fibrosis in a rheumatoid patient. (Courtesy Steven P. Brownstein, MD, Springfield, NJ.) |

The criteria for the diagnosis of RA, which were designed originally to aid in research consistency, have been revised and are now easier for the clinician to use. 22 The diagnosis can be made if the patient meets at least four of the following criteria established by the American College of Rheumatology. The first four must be present for at least 6 weeks.

1. Stiffness in the morning that lasts at least 1 hour

2. Swelling of at least three joints

3. Swelling of the wrist, MCP, or PIP joints

4. Symmetric swelling

5. Rheumatoid nodules

6. Positive rheumatoid factor test

7. Radiographic changes consistent with RA

The joint stiffness is sometimes termed jelling phenomenon and occurs in the morning or after periods of inactivity. Jelling also is described in fibromyalgia.

Although the main sites affected by RA are the joints, extraarticular manifestations are common. Rheumatoid nodules are the classic extraarticular lesions. These subcutaneous lesions are found in approximately 25% to 40% of patients and are typically located on the extensor surfaces at sites subject to trauma. 406,610 These nodules also can be present in visceral organs. Pulmonary and cardiovascular systems often are affected in patients with RA. Two syndromes associated with RA are Felty (a combination of RA, splenomegaly, and neutropenia) and Sjögren (marked by RA and dry eyes and mouth). A laboratory clue to Felty syndrome is decreased white blood cells, which occurs with splenomegaly.

Patients with RA tend to have reduced life expectancies and decreases in their ability to perform activities of daily living and work. 454,510 The disease course is variable, ranging from mild with periods of remission to severe and quickly progressive. The highest rate of joint damage and progression occurs early in the disease; therefore treatment should begin immediately after the diagnosis is made so that irreversible joint damage is prevented. 652 Known risk factors may increase the possibility of developing the severe stages of the disease and early mortality, so these patients may need a more aggressive treatment. 509,510,658,661

Laboratory tests.

Laboratory tests aid in establishing the diagnosis and assessing disease activity. The test for the presence of rheumatoid factor is positive in approximately 70% to 80% of patients with RA (95% if presenting with subcutaneous nodules) but also is positive in approximately 5% of individuals who do not have RA, and in patients with other nonrheumatoid diseases. 368,384 Therefore a positive or negative rheumatoid factor test must be correlated closely with other clinical features. A complete blood count, ESR, C-reactive protein, and ANA assay also may be performed to initially evaluate and as follow-up for rheumatoid patients. 684

Treatment and management.

RA has become one of the most costly musculoskeletal disorders because of loss of work and limitations in daily activities caused by pain and functional disability, 6,10,194,693 and because of the associated treatment cost. More aggressive treatment is being used at the initial onset of RA to combat unfavorable long-term outcomes. 650,656

Treatment is multifaceted and geared toward reducing pain and limiting or slowing the progression of deformities and associated disability. Conservative therapy should include patient education (inclusive of pain coping techniques) and emotional support; 318,367,645 rest; application of heat or cold; dietary changes or supplementation; and resistance training, exercise, and joint mobilization to improve joint range of motion, strengthen muscles, and minimize joint deformity. *

Pharmacologic treatment includes nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), corticosteroids, and more aggressive second-line of therapy or disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), such as antimalarial drugs, intramuscular gold, and penicillamine. Infliximab and etanercept are biologic response modifiers that block specific immune factors leading to RA; these treatments have now been approved as second-line therapy. Third-line drugs or immunosuppressants inhibit the immune system and may have serious side effects. 65,610

At the disease onset, radiographs of the hands, wrists, and feet should be obtained as a baseline and then repeated at 6-month intervals for a minimum of 2 years to aid in identifying those patients at risk for serious joint damage and deformity. 85,494 MRI of the spine should be performed on patients with radiographic abnormalities combined with neurologic deficits, and should be considered in patients with superior migration of the dens, a PADI of less than 14 mm, and a subaxial canal diameter of less than 14 mm regardless of symptoms. MRI with contrast (gadolinium) should be used to differentiate synovial fluid from pannus. Surgical intervention may be indicated to replace joints (Fig. 9-25), correct severe deformity, 229 or treat neurologic compromise. 207

|

| FIG. 9-25 A, Anteroposterior and, B, lateral radiographs showing changes typically associated with rheumatoid arthritis of the knee. The most striking finding is tricompartmental loss of joint space and joint effusion. Small marginal osteophytes indicate secondary osteoarthritis (arrows). C and D, Because of ongoing pain and disability related to the advanced rheumatoid arthritis, the patient underwent total resurfacing knee arthroplasty. |

• Females are more likely to develop the disease than men (two or three times more likely, less in older populations), with the peak incidence occurring between 40 and 70 years of age.

• The primary sites affected are the synovial tissues of the hands, feet, wrists, hips, knees, elbows, and shoulders. Affected metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints of the hand and atlantoaxial subluxation of the cervical spine are most characteristic. The sacroiliac articulations are rarely affected.

• This arthritide is marked by a bilateral symmetric distribution, periarticular soft-tissue swelling, initial juxtaarticular osteoporosis progressing to generalized uniform loss of joint space, marginal erosions (bare areas) progressing to subchondral erosions, subchondral cysts, and joint deformities.

• Hip involvement may lead to bilateral acetabular protrusion.

• Subluxations and joint deformities, including swan neck, boutonnière, and hitchhiker’s thumb, are characteristic.

• Treatment is directed toward limiting pain and disability and may include surgery for joint replacement or to address neurologic complications.

Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis

BACKGROUND

In the United States juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA) and juvenile chronic arthritis (JCA) are terms often used interchangeably to encompass the three major subsets of JRA, whereas in Europe the designation of JCA includes not only JRA (and its subsets), but also the addition of the juvenile spondylarthropathies (ankylosing spondylitis [AS], enteropathic arthritis, and psoriatic arthritis). 104,105,689 To unify these previous classifications and decrease confusion, which in turn would facilitate research and aid in identification of homogeneous groups of children, a new classification known as juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) has been developed. 506,639 The definition of JIA basically is consistent with the definitions of JRA and JCA, although additional subsets have been added to the new classification system.

Classification according to the International League against Rheumatism: JIA

1. Systemic arthritis

2. Oligoarthritis

a. Persistent

b. Extended

3. Polyarthritis (rheumatoid factor negative)

4. Polyarthritis (rheumatoid factor positive)

5. Enthesitis-related arthritis

6. Psoriatic arthritis

7. Other or unclassified arthritis

Classification according to the American College of Rheumatology: JRA

1. Systemic

2. Pauciarticular or monoarticular

3. Polyarticular

a. Seronegative

b. Seropositive

Classification according to the European League against Rheumatism: JCA

1. Juvenile-onset adult type (seropositive)

2. Seronegative chronic arthritis (Still’s disease)

a. Classic systemic disease

b. Polyarticular

c. Pauciarticular or monoarticular

3. Juvenile spondyloarthropathy (AS, psoriatic arthritis, enteropathic arthritis)

The terms JIA, JRA, and JCA all indicate an inflammatory disease of unknown cause, occurring in childhood (<16 years of age), characterized primarily by arthritis (joint inflammation and stiffness) persisting for a minimum of 6 weeks (JCA symptoms must last at least 3 months). The term juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is used in this book.

JIA is the most common type of arthritis affecting children. 677 It is an autoimmune disorder with a prevalence that appears to range between 12 and 148 cases per 100,000, 503,601,646 and an incidence rate of 17 per 100,000, that appears to on the decline. 304,503 It targets predominantly the synovial joints, in which synovial proliferation leads to joint and soft-tissue destruction. It is suspected that genetics may predispose a patient to the disease, and an infectious or environmental factor may trigger its onset.

The first four subsets of the new classification system of JIA encompass the vast majority of cases and are essentially the same subsets listed by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) as representative of JRA. They are the main focus of this section. They are divided according to the presence or absence of rheumatoid factor, systemic symptoms within the first 6 months of onset, and number of joints involved within the first 6 months of onset. Subsets 1, 2, and 3 comprise approximately 70% of all JIA patients. Subset 4 represents approximately 5% to 10% of all JIA cases.

1. Systemic arthritis (essentially classic systemic onset disease) is the most serious. It occurs in children under 5 years of age; affects males and females equally; and presents with spiking fevers, a characteristic salmon-colored rash on the trunk and thighs, hepatosplenomegaly, serositis, adenopathy, leukocytosis, and mild polyarthritis, usually of the wrist, knees, and ankles.

2. Oligoarthritis (essentially pauciarticular or monoarticular) is the most common variety, and is found in young children under 5 years of age and affects no more than four joints during the first 6 months, generally affecting large joints (e.g., knees, ankles, elbows, wrists). This form frequently is accompanied by asymptomatic chronic iridocyclitis, uveitis, cataracts, and (in a minority) blindness. There is a large association with antinuclear antibodies. Two additional subcategories are recognized: persistent oligoarthritis and extended oligoarthritis. Persistent oligoarthritis affects no more than four joints throughout the course of the disease. Extended oligoarthritis affects a cumulative total of five or more joints after the first 6 months of onset.

3. Polyarthritis (rheumatoid factor negative, essentially polyarticular seronegative) involves more than five joints during the first 6 months of the disease, is more prevalent among females between 12 and 16 years of age, and has an early onset between the ages of 1 and 3 years. Symmetric small joint involvement of the hands and feet is common, which is similar to the distribution of adult RA.

4. Polyarthritis (rheumatoid factor positive, essentially polyarticular seropositive) develops in teenage girls and is similar clinically and radiographically to adult RA. 15,572 Juvenile patients may present with subcutaneous nodules, although this symptom occurs less frequently in juveniles than adults. More than five joints are affected, most commonly the hands, wrists, feet, knees, hips, and cervical spine.

5. Enthesitis-related arthritis usually occurs in males over 8 years old and indicates the presence of arthritis and enthesitis, or arthritis or enthesitis with at least two of the following: SI tenderness or inflammatory spinal pain, presence of HLA-B27, or family history of confirmed HLA-B27 in at least one first- or second-degree relative.

7. Other or unclassified arthritis indicates childhood arthritis of unknown cause persisting for at least 6 weeks that does not fulfill criteria for subsets 1 to 6, or fulfills criteria for more than one of the other subsets.

IMAGING FINDINGS

Although other imaging modalities may be more sensitive for early detection of joint pathology, plain film radiography continues to be the primary method of imaging for the diagnosis and follow-up evaluation of JIA. The radiographic presentation in the majority of JIA cases is similar in appearance to adult RA with few exceptions (Table 9-2). Although features within each subset of JIA can differ, there are features that may be common to all. These include early manifestations such as fusiform periarticular soft-tissue swelling and juxtaarticular osteopenia (which may include growth recovery lines) that may become diffuse. Intermediate or later-stage manifestations may include joint space narrowing, osseous erosions, growth disturbances, bony ankylosis, joint contractures, subluxation, or dislocation. Early plain film radiographs may be negative, and a technetium bone scan, CT, or MRI may be more helpful.

| Radiographic finding | Juvenile rheumatoid | Adult rheumatoid |

|---|---|---|

| Joint space narrowing | Common in late stages of disease | Common in early stages of disease |

| Marginal bony erosion | Common in late stages of disease | Common in early stages of disease |

| Intraarticular fusion | Common | Uncommon |

| Growth abnormalities | Common | Absent |

| Periostitis | Common | Absent |

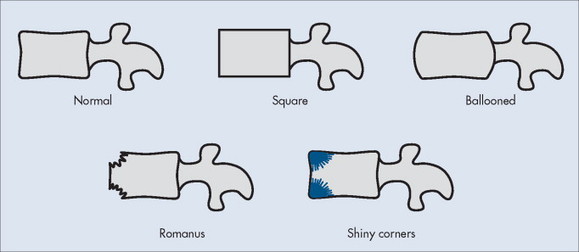

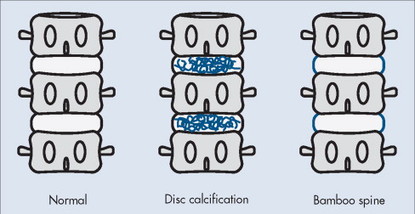

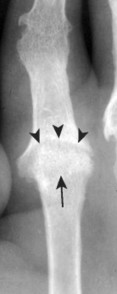

Distinct features of JIA include periostitis and growth abnormalities, which are the result of the disease process combined with skeletal immaturity. Periostitis commonly involves the diaphysis of the metacarpals, metatarsals, and proximal phalanges and may be an early and prominent finding that is likely explained by the exposure of loosely attached periosteum to an inflammatory and hyperemic process. Growth abnormalities result from hyperemia to the epiphysis and growth plates, causing an overgrown “ballooned” or “squared” epiphysis. Hyperemia also may lead to premature growth plate fusion, resulting in shortening of limbs or limb length discrepancies.

Overall joint involvement mimics that of adult RA in the majority of cases, although JIA has more of a predilection for large joints. Individual joint manifestations are noted in the following explanations.

Knees.

The knee is the most commonly affected joint in JIA. Effusion; joint space narrowing; osteopenia and enlargement, or “ballooning” of the metaphysis and epiphysis of the distal femur and proximal tibia; widening or expansion of the intercondylar notch; and patellar squaring are the most distinctive findings associated with JIA in the knee (Fig. 9-26). Growth arrest lines may result from temporary reduction in growth velocity, and frequently are seen around the knee. A discrepancy in leg lengths may occur with knee inflammation. If the inflammation is controlled and occurs before the age of 9, the leg lengths equalize and no residual discrepancy remains. If involvement exists after the age of 9, early epiphyseal closure may occur and result in a permanently shorter leg on the involved side. 600

|

| FIG. 9-26 A, Anteroposterior and, B, lateral knee radiograph in a patient with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. The femoral condyles are enlarged and the intercondylar notch is widened, both of which are common features of the disease in this joint. (Courtesy Steven P. Brownstein, MD, Springfield, NJ.) |

Ankles and feet.

Swelling may be noted on the dorsum of the foot because of involvement of the subtalar and tibiotarsal joints (Fig. 9-27). Tibiotalar slant, valgus, and varus deformities may result. 545

|

| FIG. 9-27 Juvenile idiopathic arthritis. A, Symmetric findings include generalized osteopenia, diaphyseal overtubulation, widespread joint space narrowing, evolving ankylosis (arrows), and diffuse muscle wasting. B, Another patient exhibits widespread ankylosis (arrows) in the hindfoot and midfoot with a cavus deformity secondary to the disease and stabilizing surgery. Osteopenia and muscle atrophy also are evident. Differential diagnosis should include consideration of other causes of disuse beginning in childhood, and certain congenital foot deformities. (From Sartoris DJ: Musculoskeletal imaging: the requisites, St Louis, 1996, Mosby.) |

Hands and wrist.

Early findings include soft-tissue swelling and juxtaarticular osteoporosis of the carpals, MCPs, and PIPs; preservation of joint space; lack of erosions; and periosteal new bone formation, resulting in a widened midportion of the phalanges (Figs. 9-28 and 9-29). Accelerated skeletal maturation; osseous erosions in the carpus, distal radius, and ulna; joint space narrowing; carpal and carpometacarpal ankylosis; and boutonnière and swan neck deformities (see description in previous section of adult RA) may present in later stages. Growth defects may be seen in the ulna and the fourth and fifth metacarpal bones (positive metacarpal sign).

|

| FIG. 9-28 Juvenile idiopathic arthritis demonstrating enlarged radial and ulnar epiphyses, carpals, osteoporosis, thin cortices, and soft-tissue swelling in this 14-year-old boy. (Courtesy Steven P. Brownstein, MD, Springfield, NJ.) |

|

| FIG. 9-29 A and B, Bilateral symmetric expression of osteoporosis, soft-tissue swelling, carpal and hand joint erosions, and enlarged epiphysis of the distal radius and ulna consistent with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. (Courtesy Steven P. Brownstein, MD, Springfield, NJ.) |

Hips.

JIA may be indicated by lack of growth of the iliac bone, femoral head flattening and enlargement, early growth plate closure, coxa valga deformity, and acetabular protrusion. Osteonecrosis also may develop as a complication of the disease but more often is related to treatment (corticosteroids).

Cervical spine.

Atlantoaxial subluxation and odontoid erosions occur, but not as frequently as in patients with adult-onset RA. Cervical spine flexion and extension radiographs should be a consideration. Apophyseal joint ankylosis may occur after facet erosions in the upper and middle cervical spine (Fig. 9-30), and appears to be the most common abnormality of the cervical spine occurring more frequently at multiple levels than at a single level. 172,343,344,401 The ankylosis is thought to cause vertebral body and disc hypoplasia. The so-called juvenile cervical vertebra is more commonly found in patients with early-onset disease172,344 than in those with late-onset disease.

|

| FIG. 9-30 Juvenile idiopathic arthritis with vertebral hypoplasia and fusion of the posterior joints (arrow) in the cervical spine. Although inflammation may affect the posterior facets in both adult and juvenile forms of rheumatoid arthritis, resultant apophyseal fusion is common in children and unlikely in adults. Vertebral body and disc hypoplasia also are prominent features in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. (Courtesy Jack C. Avalos, Davenport, IA.) |

Mandible.

Micrognathia may be observed clinically, but more often radiographically in children with JIA.

Radiographic changes in enthesitis-related arthritis.

The SI joint is involved, but usually not at the onset of the disease. There is widening of the joint space with erosions on the inferior aspects of both articulating surfaces. CT may best assess these changes given the presence of a normally wide SI joint space in children. In the feet, the MTP and IP joints of the first digit frequently are affected. Plantar enthesitis also may be noted. Hip involvement may be noted with enlargement of the femoral epiphysis, iliofemoral joint space narrowing, and femoral neck osteophytosis (similar to that seen in adult AS).

CLINICAL COMMENTS

Presentation.

Because there is no single test to diagnose JIA, it is considered a diagnosis of exclusion, 76 as other conditions such as infection; trauma; congenital, hematologic, and collagen vascular disorders; and malignancies are eliminated. The clinical presentation may be a child with persistent joint swelling, pain, and stiffness; a painless limp; or a presentation with systemic symptoms (e.g., fever, rash, lymphadenopathy). Symptoms should be present for 6 weeks before the diagnosis of JIA is made. Children with JIA may be undersized and have generalized or localized growth abnormalities.

Laboratory abnormalities.

Laboratory abnormalities reflect the inflammatory process, and studies are used only to support the clinical suspicion of or monitor the progression of JIA. Depending on the subtype, anemia, leukocytosis, proteinuria, antinuclear antibodies, rheumatoid factor, HLA-B27, and an elevated ESR may be present.

Therapy and management.

The approach to therapy is similar to that for adult-onset RA and varies depending on the course of the disease. It should focus on pain relief, preservation of joint function, maintenance of normal growth and muscle strength, and psychosocial development. Adequate nutrition is essential. Active exercise, maintaining joint range of motion, and physical therapy may aid in preserving or restoring joint space and leading to clinical improvements. 491 Aspirin and NSAIDs usually are given to help with inflammation, whereas the use of systemic corticosteroids initially is avoided because growth retardation is a major complication, but may be used in low doses, or for children with life-threatening complications, and topically for eye involvement. The more “hard-core” second- or third-line therapies are considered with unresponsive patients or those with life-threatening systemic disease. Ophthalmologic examinations should be given at least semiannually to detect asymptomatic iridocyclitis. Eye examinations are given more often in ANA-positive patients.

• Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA) and juvenile chronic arthritis (JCA) are often used synonymously in the United States, whereas the additional subset of juvenile spondylarthropathies is included with JRA to form JCA in Europe. For unification, a new classification, juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), has been developed to encompass and expand on these two systems.

• JIA is the most common childhood arthritis, affecting children under 16 years of age.

• The subsets of JIA are based on the number of joints involved, systemic involvement, and the presence or absence of rheumatoid arthritis factor.

• Although joint involvement mimics that of adult rheumatoid arthritis, JIA has a greater predilection for large joint involvement and intraarticular fusion. Periostitis and growth abnormalities are noted in juvenile-onset disease, and not adult-onset disease.

• Hands, wrists, knees, hips, and the cervical spine are commonly affected.

• Therapy is similar to that used for adult rheumatoid arthritis, although more caution is used with regard to use of corticosteroids and more “hardcore” lines of defense because of the potentially devastating side effects.

Seropositive and Connective Tissue Arthropathies

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

BACKGROUND

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an inflammatory connective tissue disorder that involves multiple organ systems and is characterized by excessive immunoreactivity (an autoimmune disorder) in which the antibodies are directed against cell nuclei. 457,540 Although the factor that activates this immune response is unclear, a major element of the underlying pathogenesis is widespread vasculitis, which may be secondary to local deposition of immune complexes. 39 Virtually any tissue can be damaged, but the joints, skin, kidneys, and serosal membranes are most frequently affected. 70,346 There is a genetic predisposition or a familial link associated with SLE. In addition, factors known to trigger flare-ups include exposure to sunlight and certain medications.

SLE usually follows an irregular chronic course of exacerbations and remissions. The mean length of time between the initial onset of symptoms and diagnosis is 5 years. The prevalence of SLE is approximately 24 cases per 100,000, 288 with some evidence of an increasing incidence rate. 648 Recent population-based studies reveal that SLE may now occur at a later age of onset, 30 to 50 years, 268,295,418,648 than the previously reported range of 20 to 40 years. Women are affected up to nine times more often than men, 288 and the most significant ratio variance occurs during the childbearing years. The ratio appears to lessen if disease onset occurs in childhood or at more than 50 years of age. SLE typically occurs 5 to 10 years earlier in women than men, although this difference may be limited to white patients. 418 In the United States, blacks are at a higher risk than whites for the development of SLE; in addition, the age at diagnosis is approximately 7 years younger among blacks. 418

IMAGING FINDINGS

Although up to 90% of patients complain of articular problems, prominent and severe radiographic changes are uncommon. 342 The most frequently affected joints are the hands, feet, wrists, and knees. Soft-tissue swelling and minimal periarticular osteoporosis are the earliest radiographic manifestations and usually present bilaterally and symmetrically. Joint deformities may ensue in later stages. Subcutaneous calcifications (calcinosis cutis) are not common in SLE, but when they occur they have a predilection for the lower extremities and can be diffuse or nodular. 675 These calcific densities are prone to ulceration and infection.

Hands.

In the hands, SLE has a joint distribution similar to RA, affecting the MCPs and PIPs. 456,543 Joint spaces typically are not narrowed. Chronic joint inflammation and effusion may lead to ligamentous laxity and result in joint deformities. The most common deformities include ulnar deviation at the MCPs, flexion and extension deformities of the IP articulations resembling swan neck and boutonnière deformities, and malalignment of the first carpometacarpal joint. These deformities are typically nonerosive and reducible (Jaccoud’s-type) and therefore are more visible on an oblique or lateral radiograph of the hand as compared with a postero-anterior radiograph, in which the pressure of the cassette may make the subluxations less pronounced. These nonerosive, flexible deformities are considered pathognomonic and are present in less than one half of patients with SLE who demonstrate articular abnormalities. Rarely these deformities eventually become permanent or fixed. Erosive changes may be seen with lupus, if subtle, and periarticular MRI may be needed for their detection. 474

Axial skeleton.

Although spinal changes are uncommon, atlantoaxial subluxation has been reported in patients with SLE. It is wise to obtain a lateral cervical flexion radiograph because this abnormality may be present and not apparent on a neutral lateral radiograph. 28

Unilateral or bilateral sacroiliitis, with radiographic features that are similar to those associated with seronegative spondylarthropathies, has been reported as an uncommon manifestation of SLE. 337

Chest.

Plain film chest radiography may be normal, or may reveal pleural or pericardial effusion, acute infiltrate, interstitial reticulation, or cardiomegaly. High-resolution chest CT may find evidence of airway disease and interstitial lung disease in patients without respiratory symptoms and with normal chest radiographs. 31,191 Chronic intersitial changes appear to predominate in the lower lung fields. 471

Osteonecrosis.

Avascular necrosis is a common complication in patients with SLE. The radiographic features are identical to those associated with osteonecrosis caused by factors other than SLE (see Chapter 11). The femoral condyle, humeral head, and femoral head are the most common sites involved; the latter is most affected. Other common sites include the proximal tibia and distal tibia. Although high doses of corticosteroids can significantly increase the risk of osteonecrosis, some treatment regimens may reduce this risk. 260 The disease process itself also seems to increase risk for developing osteonecrosis, because patients not receiving steroids also develop this condition. 336

Presentation.

The revised criteria for SLE must include four of the following: 629

• Malar rash

• Discoid rash

• Photosensitivity

• Oral ulcers

• Arthritis

• Serositis

• Renal disorder

• Neurologic disorder

• Hematologic disorder

• Immunologic disorder

• Antinuclear antibody

The clinical presentation varies according to the distribution of lesions and extent of systemic involvement. Many patients initially present with constitutional signs and symptoms (malaise, fever, and weight loss), polyarthritis, or a skin rash. The classic malar “butterfly” erythema may be noted but is only one of several cutaneous lesions that may present intermittently during the course of the disease. 346 The renal system is almost always involved, but the extent differs widely from one patient to the next. 18 Manifestations in any organ system (e.g., respiratory, cardiac, gastrointestinal, central nervous) may appear eventually. 579 Associated life-threatening conditions may include intestinal perforation and vasculitis, seizures, stroke, pulmonary embolus, and nephritis. Pregnancy may be related to an increase in the disease morbidity. 504

Laboratory tests.

The screening test for SLE detects the presence of ANAs, which are present in virtually all patients with SLE. Although this test is sensitive for SLE, it is not specific and therefore may be positive in nonlupus conditions. However, the presence of antibodies to native (double-stranded [ds]) DNA and anti–Sm antibodies strongly suggests SLE. Lupus erythematosus cells* also may be observed. Rheumatoid factor is found in a minority of patients, which may indicate an overlap syndrome other than true SLE.

*ANAs react with nuclei of damaged cells, which disrupt the cells’ chromatin structures and transform them into lupus erythematosus bodies. These bodies undergo phagocytosis by neutrophils to form lupus erythematosus cells.

Treatment and management.

The diagnosis of idiopathic lupus should be made only after ruling out the possibility of a drug-induced condition, which can be concluded if discontinuing use of a suspected drug alleviates all signs and symptoms. 260 Treatment depends on the location and severity of the disease. In mild cases it may involve counseling, use of sunscreen, exercise, and NSAIDs, whereas in more severe disease immediate corticosteroid or other immunosuppressive drug therapy may be necessary. 133,382 Unfortunately, the use of immunosuppressive drugs increases the risk of infection, which is currently a major cause of morbidity and mortality in these patients. 282 New drug therapies are being tested that may reduce disease activity. 263,642 Sex hormones are being investigated as potential therapeutic agents because of their immunomodulatory properties. 659

• Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an inflammatory connective tissue disorder that affects many organs (skin; vascular endothelium; central nervous system; and renal, hematologic, musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, pulmonary, and gastrointestinal organs).

• The disease is more common in blacks, 90% of cases are in women, and the majority of cases develop between 30 and 50 years of age.

• The metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints of the hands are affected, and nonerosive, flexible deformities are characteristic.

• Although not common, atlantoaxial subluxation may occur; therefore lateral flexion-extension radiographs of the cervical spine should be a consideration.

• The clinical presentation is marked by arthralgia, “butterfly” rash, ulcers in the nose and mouth, and constitutional signs and symptoms (e.g., fever and fatigue).

• Infection and nephritis are major causes of mortality in all stages of SLE.

• Laboratory tests include a test for the presence of antinuclear antibodies, anti–Sm antibodies, lupus erythematosus cells, and rheumatoid factor.

Scleroderma

BACKGROUND

Scleroderma, which literally means “hard skin,” describes progressive thickening of the skin from increased collagen deposits. The disease also is known as progressive systemic sclerosis (PSS), a term that more appropriately describes the entire disease process, because it is a connective tissue disorder characterized by small vessel disease, fibrosis, and excessive deposits of collagen that may affect not only the skin, but also the musculoskeletal system and internal organs (e.g., gastrointestinal tract, lungs, heart, kidneys). Scleroderma has been divided into two major classifications, localized and systemic, and subclassifications depend on the existence and extent of systemic involvement, as well as the rapidity of the disease progression. Localized scleroderma usually only involves the skin and may affect the musculoskeletal system to a limited degree. There are three subtypes: morphea (localized), generalized morphea, and linear scleroderma. Systemic sclerosis causes more widespread skin changes and may be associated with internal organ damage (lungs, heart, and kidneys). Systemic sclerosis has two subtypes: limited and diffuse. Systemic limited scleroderma also is known as CREST, an acronym for its most prominent features: calcinosis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, esophageal dysfunction, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasia. Systemic diffuse scleroderma is the most serious form of the disease because of its severe onset and rapid progression.

Although the etiology is unknown, genetics, hormonal events, the immune system, and an environmental agent or trigger are believed to play important roles in its pathogenesis. * A positive family history appears to be the greatest risk factor, although the familial risk is still relatively low (<1%). 23 The prevalence in the United States has been noted to be 4.4 to 27.6 cases per 100,000, 414,613 with an incidence rate reported to range between 1.4 to 1.9 cases per 100,000. 414,613 It is unclear as to whether this rate is stable or on the rise. 413,426 The female-to-male ratio has been reported as 3:1, although in the United States it is approximately 8:1, 414,612,613 with the highest rates occurring during the childbearing years. There is evidence to suggest that the age of onset is later than has been reported in earlier studies, with the age of occurrence typically 35 to 65345,414 rather than 20 to 50. 611,612 In the United States African Americans are at a higher risk of developing scleroderma compared with whites, and young African American women appear to be stricken most often and most severely. 345,414,426,613

The majority of patients with scleroderma eventually develop joint involvement. The major abnormalities discovered on plain film examination are noted in the hands and include soft-tissue atrophy, osseous resorption, and subcutaneous calcification. Gastrointestinal contrast studies may reveal characteristic findings in the esophagus, small intestine, and large bowel that are primarily caused by fibrosis and atrophy. Plain film chest radiography may be negative or reveal signs of pulmonary hypertension or interstitial fibrosis.

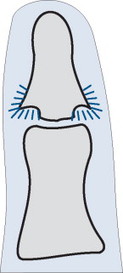

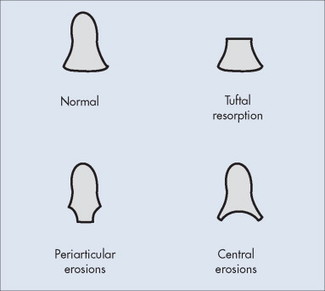

Hands.

Atrophy of the soft tissues of the fingertips (acral tapering) is a very common feature, the incidence of which increases if the patient has accompanying Raynaud’s phenomenon. 35 Involved digits often have accompanying bony changes (acroosteosclerosis, acroosteolysis) and soft-tissue calcification. Bone resorption or erosion is noted frequently, primarily involving the tufts of the terminal phalanges (acroosteolysis) (FIG. 9-31FIG. 9-32 and FIG. 9-33). 581 Resorption may of lead to a “penciled” or pointed appearance of the phalanx; most of the entire distal phalanx may be destroyed with continued resorption. Erosions also involve the DIP and PIP articulations, but to a lesser degression distal tuft. 158 Erosion at the first carpometacarpal joint is a distinctive feature also, 582 and may lead to radial subluxation of the metacarpal base. Juxtaarticular or diffuse osteoporosis may be present. Joint space narrowing and marginal erosions are noted in up to 15% of patients. 51

|

| FIG. 9-31 Scleroderma presenting on a bilateral posteroanterior hand view demonstrating characteristic resorption of the distal margins of the distal phalanges (acroosteolysis) (arrows) and foci of radiodense soft-tissue calcifications (arrowheads). |

|

| FIG. 9-32 Acroosteolysis (arrow) and soft-tissue calcifications (arrowhead) of scleroderma. (Courtesy Gary Longmuir, Phoenix, AZ.) |

|

| FIG. 9-33 Scleroderma causing prominent acroosteolysis of the hand (arrows). (Courtesy Joseph W. Howe, Sylmar, CA.) |

Subcutaneous calcifications.

The presence of subcutaneous and periarticular calcinosis is prominent in the hands and also may develop around other joints and over bony eminences (Fig. 9-34). 158,178,670 These calcifications may have a varied appearance, ranging from punctate, to sheetlike, to large focal conglomerations. Ulcerations, especially over bony prominences, may be a complicating factor. Paraspinal calcifications may lead to localized pain, stiffness, dysphagia, or neurologic compromise. 505,580

|

| FIG. 9-34 Scleroderma exhibiting subcutaneous and periarticular soft-tissue calcification (arrows) of the, A, hand and, B, feet in this 62-year-old patient. Although fibular subluxations of the phalanges at the metatarsophalangeal articulations are evident, no signs of significant erosions are present. |

Gastrointestinal tract.

The gastrointestinal tract is frequently involved in systemic scleroderma, with the esophagus being involved up to 85%. Smooth muscle dysfunction causes esophageal aperistalsis and reduced lower esophageal sphincter pressure, resulting in gastroesophageal reflux and an increased incidence of peptic stricture and Barrett’s esophagus. The esophageal changes lead to dysmotility and may be reflected on plain film as air or air-fluid levels within the esophagus. 468 Esophageal involvement may be diagnosed by a barium swallow, which shows a “stiff glass tube” appearance. Barium studies initially may reveal rapid transit; esophageal reflux; dilatation of the esophagus and small bowel; and large-mouthed sacculations or pseudodiverticula in the colon, jejunum, and ileum. Over time barium studies reveal decreased motility and possibly obstruction.

Chest.

The lung is the most commonly involved internal organ after the gastrointestinal tract. The two major pulmonary manifestations associated with scleroderma are pulmonary hypertension and interstitial lung fibrosis. Pulmonary arterial hypertension has a high mortality rate and may occur in approximately 15% of PSS patients. It may develop secondary to pulmonary fibrosis or as an isolated complication. Therefore screening procedures should include Doppler-echocardiography and pulmonary function tests. 145

If the interstitial fibrosis is extensive enough to be visible on a plain chest radiograph, it will predominate in the lower lungs. The radiographic findings are characterized by fine reticular, partly nodular fibrosis. There may be thick linear radiopacities and thickened septae near the blood vessels. In later-stage or end-stage fibrosis, a more cystic or “honeycomb” pattern appears. HRCT significantly increases early detection of alveolitis and fibrosis, given that plain film chest radiography may appear unremarkable in the early stages.

Mandible.

Thickening of the periodontal membrane may create an increase in the radiolucent area between the tooth and mandible that is best noted on dental radiographs. The involvement is most visible around the molars or posteriorly located teeth.

CLINICAL COMMENTS

The patient should fulfill the major criterion or two of the minor criteria as defined by the American College of Rheumatology. 619

• Major criterion: proximal diffuse (truncal) sclerosis (skin tightness, thickening, nonpitting induration)

• Minor criteria:

• Sclerodactyly

• Digital pitting scars or loss of substance of the digital finger pads (pulp loss)

• Bibasilar pulmonary fibrosis

Changes in the skin’s appearance (e.g., thickness and fibrosis, tightening, shininess, atrophy), Raynaud’s phenomenon, 299 and arthralgias of the fingers may be the first signs of systemic sclerosis, although visceral involvement may have occurred already. 147,280,628 A thorough, multisystem evaluation is necessary to detect serious problems that may exist in a seemingly asymptomatic patient. 359 As noted, the gastrointestinal tract is the most common internal site affected, with complications including dysphagia, gastroesophageal reflux, Barrett’s esophagus, small bowel bacterial overgrowth, malnutrition, and intestinal pseudoobstruction. 26,206,602 Periodontal membrane thickening causes loose teeth, which further complicates maintaining good nutritional status. The heart, lungs, and kidneys also may become involved; pulmonary disease causes higher mortality than renal failure. 113,147,247,359 Scleroderma renal crisis, a condition that was considered almost certainly fatal, now is being treated successfully with angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors. 611

Laboratory tests.

No single test accurately and definitively determines a diagnosis of scleroderma. Laboratory tests may reveal an elevated ESR, the presence of rheumatoid factor in approximately 30% of patients, and the presence of serum ANAs in more than 90% of cases. A variety of disease-specific autoantibodies (e.g., anticentromere antibodies, anti–Schl-70) have been discovered, and are not only useful in the diagnosis of PSS, but also provide markers for certain clinical features. 24,264

The nail fold capillary test is a useful noninvasive test that examines the skin beneath the fingernail to determine the presence or absence of normal capillary function. Absence of normal capillary function may aid in confirming a suspicion of scleroderma, given that an early sign of systemic scleroderma is the disappearance of the capillaries in the skin of the extremities. 392,573

Treatment includes patient education, avoidance of temperature extreme, cessation of smoking to reduce digital vascular complications, 245 dietary modification, physical therapy and exercise, drug therapy, and surgery. Treatment and management are directed toward the varied systemic manifestations of the disease. 427,448,459,602 No generalized therapy for progressive systemic sclerosis has been proved to be effective. Evidence suggests that drug therapy should target one or all of the involved disease processes: vascular disease, autoimmune disorder, and tissue fibrosis. The extent of specific organ involvement must be known to make an appropriate treatment decision. 621 The continuous accumulation of information about pathogenesis of fibrosis in scleroderma and the numerous therapies that are being studied provide hope for the development of a successful treatment or disease-modifying therapy for the complications of this condition. 335,343,459,570

It should be noted that certain chemical compounds (vinyl chloride), solvents (aromatic hydrocarbons), minerals (silica), pesticides, and drugs can induce scleroderma-like disease. 249,251 This should be a consideration if exposure is a possibility in the patient’s work environment or the patient’s drug history is suspicious.

• Scleroderma is a connective tissue disorder that affects the skin, musculoskeletal system, and internal organs.

• It is divided into two major classifications, limited and systemic, based on the extent of involvement.

• In the United States, women are eight times more likely to develop the condition than men.

• The disorder typically develops between 30 and 50 years of age.

• The hands develop distal tuft resorption (acroosteolysis), acral tapering caused by soft-tissue atrophy, and subcutaneous calcinosis.

• Major pulmonary manifestations include hypertension and interstitial fibrosis.

• Gastrointestinal manifestations include esophageal dysmotility and large-mouthed (wide-mouthed) bowel sacculations.

• Laboratory tests may reveal an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, the presence of rheumatoid factor in 30% of patients, and the presence of serum antinuclear antibodies in 90% of patients.

• Specific autoantibodies may aid in the diagnosis of lupus, and provide clues about the onset and prevalence of related clinical feature.

• Certain chemicals and drugs may produce scleroderma-like disease.

Polymyositis and Dermatomyositis

BACKGROUND

Polymyositis and dermatomyositis are two of the three idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. The third, inclusion-body myositis, has most recently been discovered to be a separate entity from polymyositis. The incidence of polymyositis/dermatomyositis has been noted at 0.8 cases per 100,000, with a prevalence of 5.1 cases per 100,000, 288 although these estimates may not be not reliable because the criteria used likely failed to separate inclusion-body myositis from polymyositis. 130,407 The widely used classification system61 was developed before these two entities were found to be distinct. The female-to-male ratio is approximately 2:1. 288 The age at the time of diagnosis typically ranges from 40 to 70 years, with 52 years of age being the mean onset. 393 Dermatomyositis may affect children and adults. 240 Polymyositis is rarely seen before the second decade of life.

The etiology is unknown. However, like most connective tissue disorders, it is believed that an autoimmune disorder631 is responsible for the mechanism of damage, which revolves around a genetic predisposition (there is an association with HLA genes) 208,587 and an environmental trigger or initiating factor. 539 Failure of apoptosis, or programmed cell death, is believed to play a major role in the pathogenesis of inflammatory muscle disease. 507 Both polymyositis and dermatomyositis are nonsuppurative inflammatory disorders that lead to subsequent fibrosis and degeneration of striated muscle and result in muscle atrophy and weakness. Predominant muscle involvement is that of the large muscles of the proximal portions of the upper and lower extremities. In addition, dermatomyositis involves the skin.

IMAGING FINDINGS

The radiographic manifestations of polymyositis and dermatomyositis usually are discussed by dividing them into two major categories: soft-tissue and articular abnormalities.

Soft-tissue abnormalities.

Initial soft-tissue changes are associated with swelling and edema in the subcutaneous tissue and muscle, particularly affecting the proximal appendicular skeleton in a bilaterally symmetric presentation. 616 Radiographically these changes appear as an increase in the soft-tissue density and poor delineation, blurring, or loss of the fascial plane lines. Extensive edema of the subcutaneous tissue may allow visualization of thickened septa. Chronic disease is associated with a loss of soft-tissue mass or bulk resulting from muscle atrophy and marked osteoporosis of the long bones and vertebral bodies.

Soft-tissue calcification is the most striking radiographic abnormality in polymyositis and dermatomyositis. It is uncommon in adults but occurs in approximately 25% to 50% of children (Fig. 9-35). 622 Soft-tissue calcifications can be subdivided by location into subcutaneous and intermuscular. Calcinosis cutis, or scleroderma-like subcutaneous calcifications, may appear as firm nodules or plaques commonly over bony prominences. These may be associated with skin ulcerations, infection, and pain, 132especially at sites of compression. Small, diffuse, linear or curvilinear subcutaneous calcifications also may be evident. Calcification at the fingertips may be associated with terminal tuft erosion.

|

| FIG. 9-35 Soft-tissue calcifications of dermatomyositis. (Courtesy Steven P. Brownstein, MD, Springfield, NJ.) |

Intermuscular calcifications generally are asymptomatic and predominate in the proximal large muscles of the upper and lower extremities. The classic radiographic appearance is large calcareous masses or “tumoral” deposits in the fascial planes. In severe forms they may cause loss of function or bone formation in place of calcification.

Joints.

Joint involvement occurs but is infrequent. Typically the associated arthritis is transient and nondeforming. The most common abnormalities are periarticular osteoporosis and soft-tissue swelling. Destructive joint changes have been reported, although there is discussion as to whether this erosive presentation is representative of overlap syndromes. Radiographic changes that have been described include soft-tissue swelling, small periarticular calcifications and erosions involving the DIP, PIP, and MCP articulations of the hands, and radial subluxations or dislocation of the IP joint of the thumb (“floppy thumb” sign). 91 Joint contractures may occur and are most commonly associated with dermatomyositis.

CLINICAL COMMENTS