9 Liver and Biliary System

Diagnosing liver and biliary tract disease requires, besides obtaining a solid clinical examination and a thorough clinical history, proper radiologic imaging. As in all pediatric imaging, close collaboration between the radiologist and the clinician is key to success.

Ultrasonography (US) plays an important role in imaging the pediatric liver and biliary tract. As children are optimal candidates for US, this is even more so the case than in adults. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance (MR) imaging are second-line imaging strategies, and because of radiation issues, MR imaging is preferred to CT.

The US examination should start with an overview of the whole liver and biliary tract in order not to miss abnormalities once a more focused examination of the liver is undertaken. A curved transducer with an appropriate frequency (for children who are not obese, in the range of 4 to 9 MHz) suffices. For the detection of more subtle changes in the liver architecture, a high-frequency linear transducer should be used. Assessing flow in the hepatic veins, portal veins, and hepatic artery should be seen as a standard part of liver imaging as abnormalities in flow can lead to a correct diagnosis of disease. For a proper evaluation of the biliary tract, it is important that the patient has fasted before the examination. A normal distended gallbladder is a sign that the patient has indeed fasted ( Fig. 9.1 ).

In addition, imaging of the liver is incomplete if the spleen is not evaluated (see Chapter 10).

Tips from the Pro

Younger children, in general, do not hold their breath if you ask them to do so. However, if you make it a challenge (e.g., a game between the child and radiologist), you will be amazed about how long they can hold their breath.

9.1 Normal Anatomy and Variants

The liver is the largest solid organ of the human body, accounting for approximately 2 to 3% of the total body weight. In young children, the liver is relatively large compared to the liver in adolescents and adults ( Table 9.1 , Table 9.2 , Table 9.3 , Table 9.4 ). The anatomy of the liver can be described in two ways: anatomically and functionally. The anatomical description is based on the external surface anatomy and as such is not useful in daily clinical practice. The functional anatomy is based on the relationship between vessels and the biliary tract. Claude Couinaud (1922–2008) was the first to recognize the importance of this functional segmentation in relation to surgery. For imaging purposes, the liver is divided into eight segments ( Fig. 9.2 ). The middle hepatic vein divides the liver into left and right lobes.

Gestational age (weeks) | Liver length in the midclavicular line (cm) | ||

No. of patients | Mean length (±1 SD) | Minimum–maximum | |

24–31 | 29 | 3.7 (0.7) | 2.8–5.8 |

32–35 | 33 | 4.6 (0.7) | 3.2–6.2 |

36–37 | 35 | 5.4 (0.6) | 3.5–6.3 |

38–41 | 153 | 5.5 (0.8) | 3.9–7.8 |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation. Source: Reprinted with permission of Elsevier from Soyupak SK, Narli N, Yapicioglu H, Satar M, Aksungur EH. Sonographic measurements of the liver, spleen and kidney dimensions in the healthy term and preterm newborns. Eur J Radiol 2002;43(1):73–78. Note: An ultrasonographic study was performed in 261 healthy newborn infants. Craniocaudal dimensions of the liver in the midclavicular line were determined. | |||

Age (years) | Liver length in the midclavicular line (cm) | ||

No. of patients | Mean (SD) | Limits of normal | |

0–0.25 | 53 | 6.4 (1.0) | 4.0–9.0 |

0.25–0.5 | 40 | 7.3 (1.1) | 4.5–9.5 |

0.5–0.75 | 20 | 7.9 (0.8) | 6.0–10.0 |

1–2.5 | 18 | 8.5 (1.0) | 6.5–10.5 |

3–5 | 27 | 8.6 (1.2) | 6.5–11.5 |

5–7 | 30 | 10.0 (1.4) | 7.0–12.5 |

7–9 | 38 | 10.5 (1.1) | 7.5–13.0 |

9–11 | 30 | 10.5 (1.2) | 7.5–13.5 |

11–13 | 16 | 11.5 (1.4) | 8.5–14.0 |

13–15 | 23 | 11.8 (1.5) | 8.5–14.0 |

15–17 | 12 | 12.1 (1.2) | 9.5–14.5 |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation. Source: Reproduced with permission of the American Journal of Roentgenology from Konus OL, Ozdeimer A, Akkaya A, Erbas G, Celik H, Isik S. Normal liver, spleen, and kidney dimensions in neonates, infants, and children: evaluation with sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1998;171(6):1693–1698. Note: This study included 307 pediatric subjects (169 girls and 138 boys). The age range was from full-term newborns (5 days) to 16 years. The subjects were imaged in the supine position. The upper margin of the midclavicular liver dimension was defined as the uppermost edge under the dome of the diaphragm; the lower margin was defined as the lowermost edge of the lobe. | |||

Age (years) | Diameter of common bile duct (mm) | 95% confidence interval |

0 | 0.7 | 0.2–1.6 |

1 | 1.2 | 0.2–1.7 |

2 | 1.0 | 0.3–1.8 |

3 | 1.3 | 0.3–1.9 |

4 | 1.1 | 0.4–2.0 |

5 | 0.8 | 0.5–2.1 |

6 | 1.2 | 0.5–2.2 |

7 | 1.3 | 0.6–2.3 |

8 | 1.5 | 0.6–2.4 |

9 | 1.9 | 0.7–2.5 |

10 | 1.7 | 0.7–2.6 |

11 | 1.7 | 0.8–2.7 |

12 | 1.9 | 0.8–2.8 |

Source: Adapted from Hernanz-Schulman M, Ambrosino MM, Freeman PC, Quinn CB. Common bile duct in children: sonographic dimensions. Radiology 1995;195:193–195. Note: This study included 173 children (100 boys and 73 girls) ranging in age from 1 day to 13 years (median age, 5.0 years). The diameter of the common bile duct was ≤ 3.3 mm in all children. | ||

Gallbladder volume (mL) | ||

Term neonates | Preterm neonates | |

Number of observations | 46 | 50 |

At birth | 1.1 (0.2–2.4) | 0.7 (0.1–1.2) |

At 6 hours after birth | 1.0 (0.2–2.2) | 0.7 (0.1–1.2) |

Number of observations after regular feeding | 46 | 50 |

After 3 hours of fasting | 0.08 (0–0.02) | 0.08 (0–0.2) |

After 6 hours of fasting | 0.7 (0.1–1.3) | 0.3 (0.1–0.9) |

Source: Reprinted with permission from Ho ML, Chen JY, Ling UP, Su PH. Gallbladder volume and contractility in term and preterm neonates: normal values and clinical applications in ultrasonography. Acta Paediatr 1998;87:799–804. Note: Ultrasound assessment of gallbladder volume (length × width × height × π/6) was performed in 50 preterm infants (mean gestational age, 31.7 ± 2.5 weeks) and 46 term infants (mean gestational age, 38.3 ± 1.2 weeks). | ||

The liver vasculature has many normal variants, ranging from a relatively commonly seen accessory hepatic vein draining directly into the inferior caval vein ( Fig. 9.3 ) to hepatic arteries arising from the superior mesenteric arteries. The same holds true for the biliary anatomy, as the classic anatomy (in which the right and left hepatic ducts drain into a common hepatic duct) occurs in only 58% of the population. For surgical planning, these normal variants can be of importance, and in complex cases, cross-sectional imaging with CT or MR imaging is warranted.

In pediatric radiology, it is important, when caring for neonates, to be aware of the fetal vascular anatomy. Especially in premature infants, the umbilical vein and the ductus venosus can be visualized, and sometimes a closing vein can be depicted ( Fig. 9.4 ; Video 9.4).

9.2 Normal Measurements

9.2.1 Portal Venous Flow

The portal vein in children shows a homogeneous hepatopetal flow in the range of 20 cm/s ( Table 9.5 ; Fig. 9.5 ); this is comparable to the adult situation. Respiration leads to a slight fluctuation in the flow pattern.

Portal venous diameter | ||

Age (years) | Mean (mm) | Limits of error |

0 | 4.5 | 3.0–6.3 |

1 | 5.7 | 3.6–7.8 |

2 | 6.5 | 4.2–8.8 |

3 | 7.0 | 5.5–8.5 |

4 | 6.8 | 5.5–8.2 |

5 | 7.0 | 5.2–8.7 |

6 | 7.7 | 5.0–10.3 |

7 | 7.7 | 4.8–10.6 |

8 | 7.2 | 5.3–9.0 |

9 | 7.6 | 5.7–9.5 |

10 | 8.2 | 5.0–11.3 |

11 | 8.7 | 6.1–11.3 |

12 | 9.5 | 6.7–12.1 |

13 | 9.2 | 6.9–11.4 |

14 | 9.0 | 6.2–12.0 |

15 | 10.2 | 9.0–11.5 |

16 | 11.0 | 7.8–14.2 |

Source: Table created from data within Patriquin HB, Perreault G, Grignon A, et al. Normal portal venous diameter in children. Pediatr Radiol 1990:20:451–453, with kind permission from Springer Science+Business Media. Note: The study included 150 children, ages 0 to 16 years, without clinical evidence of liver or intestinal disease referred for abdominal Ultrasound. The portal vein was visualized in the longitudinal axis from the splenomesenteric junction to the liver hilum. The greatest anteroposterior (AP) diameter was measured at the site where the hepatic artery crosses the portal vein. | ||

9.2.2 Hepatic Arterial Flow

The hepatic artery shows a hepatopetal arterial flow with a characteristic low-resistance and high-velocity diastolic flow ( Fig. 9.6 ). In adults, the reported peak systolic flow is 30 to 40 cm/s, and the end-diastolic flow is 10 to 15 cm/s.

9.2.3 Hepatic Venous Flow

The hepatic veins show a triphasic flow consisting of two waves toward the heart (i.e., atrial diastole and ventricular systole) and a small wave away from the heart (i.e., atrial systole) ( Fig. 9.7 ).

Tips from the Pro

Children love it when you tell them that they have a bunny in their tummy. If you try, you can depict the hepatic veins as resembling the well-known playboy bunny sign™ ( Fig. 9.8 ).

9.3 Pathology

9.3.1 Congenital Anomalies

Biliary Atresia

Biliary atresia is a congenital obstruction of the intra- and/or extrahepatic ducts, usually presenting with neonatal jaundice. The overall incidence is approximately 1 in 15,000 births, but it is far more common in the Asian population.

The most common finding on US (seen in almost two-thirds of neonates with biliary atresia) is an absent, small (< 1.5 cm), or empty gallbladder in a neonate who has been fasting for several hours ( Fig. 9.9 a). Furthermore, a triangular or tube-shaped echogenic focus with a thickness of 4 mm or more that follows the portal veins can be seen at the porta hepatis ( Fig. 9.9 b). This so-called triangular cord sign has a reported sensitivity of 62 to 93% and a specificity of 96 to 100%, but can be difficult to distinguish from periportal echogenicity due to inflammation or cirrhosis. Other signs that suggest the presence of biliary atresia include an absent common bile duct, a hypertrophic hepatic artery ( Fig. 9.9 b,c), and increased hepatic subcapsular flow on color Doppler US ( Fig. 9.9 d).

Choledochal Cysts

Choledochal cysts are rare congenital saccular or fusiform dilatations of the biliary tree with an incidence of approximately 1 to 2 in 100,000 to 150,000 live births. Again, they are far more common in the Asian population, with a reported prevalence of 1 in 1,000 persons in Japan. Choledochal cysts are usually classified according to Todani into five subtypes ( Fig. 9.10 ). Type I cysts, the most common, occur in up to 80 to 90% of all cases ( Fig. 9.11 and Fig. 9.12 ). They are often associated with an abnormal junction of the common bile duct with the pancreatic duct. Frequent complications include ascending cholangitis and/or pancreatitis, liver cirrhosis, portal hypertension, and spontaneous cyst rupture. There is an increased risk for developing cholangiocarcinoma, especially after the age of 10 years. In cases of delayed presentation, these cysts can become extremely large ( Fig. 9.13 ).

With US, the location and degree of bile duct dilatation can be easily depicted. Sludge or bile stones can be identified by bile stasis in the dilated ducts. In type V choledochal cysts (Caroli disease), the kidneys should be examined as well because this type is often associated with autosomal-recessive polycystic kidney disease ( Fig. 9.14 ). Pathognomonic for Caroli disease is the so-called central dot sign ( Fig. 9.15 ), which is the result of fibrovascular bundles, consisting of portal vein and hepatic artery branches, crossing the dilated choledochal cysts. Although originally described on CT, this sign is well visualized on US.

The differentiation of a choledochal cyst ( Fig. 9.16 a–c) from a simple hepatic cyst, hepatic abscess, or pancreatic pseudocyst is sometimes difficult. Additional imaging consists of either endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), which can be performed only in specialized centers by well-trained gastroenterologists and allows intervention, and/or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), which can be performed on all modern MR scanners, although sedation may be necessary ( Fig. 9.16 d, e; Video 9.16).

Congenital Portosystemic Shunts

Congenital portosystemic shunts are rare congenital anomalies that are mostly detected on US. The children can present with abnormal liver tests, elevated blood ammonia, and/or serum bile acid levels, or the shunt can be found incidentally on US. A portosystemic shunt can be intrahepatic ( Fig. 9.17 ), in which case there is a connection between a portal vein and either a hepatic vein or the inferior caval vein, or extrahepatic, in which case the portal trunk or a branch of it is in direct contact with the inferior caval vein. Extrahepatic portosystemic shunts are classified according to Abernethy. Type I consists of an atretic portal vein with the splenic and superior mesenteric veins terminating either separately in the inferior vena cava (type Ia) or as a common venous trunk (type Ib; Fig. 9.18 ). In Abernethy type II, there is a normal or hypoplastic portal vein with partial shunting into the inferior vena cava.

Intrahepatic portosystemic shunts can regress spontaneously before the age of 2 years, but if they persist, intervention may be needed. Long-term consequences of these shunts are the development of liver tumors (see later section on focal nodular hyperplasia), hepatic encephalopathy, hepatopulmonary syndrome, and pulmonary hypertension.

9.3.2 Infection

Hepatitis

Hepatitis is an inflammation of the liver. The most common cause is viral infection, but hepatitis can also be a result of autoimmune disease, metabolic disorders, or drug use. In the acute phase, imaging plays no significant role other than to rule out other diseases. The role of imaging is the follow-up of patients with hepatitis, in which case the interest lies in the detection of cirrhosis, portal hypertension, and tumors (especially hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatitis caused by hepatitis B virus or hepatitis C virus; Fig. 9.19 ).

Pyogenic Abscess

Although relatively rare in the Western world, pyogenic liver abscesses are the most frequent abscesses encountered in children. The most common pathogen is Escherichia coli ( Fig. 9.20 and Fig. 9.21 ; Video 9.21). There is a well-known relation between appendicitis and the formation of liver abscesses; however, with the improved detection of appendicitis, this cause is decreasing. The most common pathways of infection are through the biliary tract and the portal system. Also, penetrating trauma can be the cause of abscess formation ( Fig. 9.22 ).

On US, a liver abscess usually appears as a rounded or ovoid hypoechoic lesion, but it can have a heterogeneous appearance, as well. The wall may be thick and irregular. Septa and debris can be encountered. Less commonly, pyogenic microabscesses are encountered ( Fig. 9.23 ). Although not pathognomonic, a diffuse pattern is seen in Staphylococcus aureus infection, and a clustered pattern is seen in E. coli infection.

Fungal Infections

Fungal hepatic infections are characterized by the presence of numerous microabscesses (often also present in the spleen). They are encountered in children with hematologic malignancies or a compromised immunologic system. The most common causative agent is Candida albicans ( Fig. 9.24 ). On US, four patterns have been described: wheel within wheel, bull’s-eye, uniformly hypoechoic, and focally echogenic.

Parasitic Infections

The most common parasitic infection of the liver is due to Entamoeba histolytica, and infection of the liver is actually the most common extraintestinal presentation of this infection. US does not discriminate between a pyogenic abscess and an Entamoeba abscess. However, on aspiration of the abscess, the typical chocolate-colored pus can be encountered.

Hydatid or echinococcal cysts are caused by infection with Echinococcus granulosus, which is endemic around the Mediterranean but can also be encountered in areas where sheep are bred. On US, a purely cystic lesion may be seen, but often daughter cysts and/or calcification of the cyst wall is encountered. A pathognomonic finding is the so-called water lily sign, which is seen if the endocyst becomes detached from the outer pericyst ( Fig. 9.25 ).

Cholecystitis

Cholecystitis is relatively rare in young children, but it becomes more common with increasing age when related to cholelithiasis. Acalculous cholecystitis also occurs, but usually only in critically ill children after trauma, major surgery, or burns, or during sepsis. On US, the gallbladder is typically enlarged and tender, with thickening of the wall. Pericholecystic fluid may be seen, and gallstones may be present ( Fig. 9.26 ). Cholecystitis should be distinguished from hydrops of the gallbladder. In the latter, the distended gallbladder lacks wall thickening, and patients are usually not as ill as in cholecystitis. Isolated gallbladder wall thickening without other signs of cholecystitis does occur in children with ascites and hepatitis/cholangitis.

Infectious Cholangitis

Infectious cholangitis occurs in children and usually has a bacterial origin, although viral, fungal, and parasitic infections are also possible, especially in the immune-compromised host. Infectious cholangitis is often associated with congenital or immune-related bile duct abnormalities, surgically corrected biliary atresia (Kasai procedure; Fig. 9.27 and Fig. 9.28 ), liver transplant, and certain immunodeficiency states. Therefore, the primary goal of US when infectious cholangitis is suspected is to search for anatomical abnormalities and/or obstruction of the biliary tract.

9.3.3 Acquired Biliary Pathology

Chole(docho)lithiasis

Gallstones are relatively uncommon in children, with a reported prevalence of up to 1.9%. They are more frequently detected in asymptomatic children because of the more widespread use of US. Chole(docho)lithiasis may be idiopathic ( Fig. 9.29 ), but in neonates and young infants it is often associated with sepsis, the use of diuretics, or total parenteral nutrition. In older children, gallstone formation may be related to obesity (an increasing problem in the pediatric age group; Fig. 9.30 ), sickle cell disease ( Fig. 9.31 ), hemolytic anemia, cystic fibrosis ( Fig. 9.32 ), and disease of the small bowel.

On US, gallstones will appear as echogenic foci with or without acoustic shadowing ( Fig. 9.33 and Fig. 9.34 ). Gallstones are calcified in approximately 50% of cases, particularly if associated with a hemolytic disorder. When located in the gallbladder, they often change in position with gravity. In the biliary tree, gallstones may cause biliary dilatation due to obstruction, which in most cases can be easily visualized on US ( Fig. 9.35 and Fig. 9.36 ). The differentiation of biliary sludge from small, nonshadowing gallstones may be difficult ( Fig. 9.37 ).

In children treated with ceftriaxone, pseudochole(docho)lithiasis, as a result of biliary precipitation, can be encountered. In these children, follow-up US, after the discontinuation of treatment, will show resolution of the pseudochole(docho)lithiasis ( Fig. 9.38 ).

In cases of symptomatic chole(docho)lithiasis, the surgical technique of choice is laparoscopic cholecystectomy. With this new surgical technique, new complications are encountered, the most important of which is damage to the biliary tree. There are four different types of injury, which can be classified as follows:

Type A: leakage of the cystic duct or peripheral intrahepatic biliary tract;

Type B: leakage from the common bile duct without the presence of a stricture;

Type C: stricture of the common bile duct without leakage;

Type D: complete transsection of the common bile duct with or without resection of a section of the common bile duct ( Fig. 9.39 ).

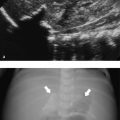

Fig. 9.39 a–c Sixteen-year-old girl with persistent abdominal pain and fever after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. a Ultrasound shows a dilatation of the proximal common bile duct (arrow), which could not be visualized more distally. b Ascites is present. c Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography shows a complete disruption of the common bile duct (arrow), with leakage of contrast into the peritoneal cavity (open arrow).

In these postsurgical patients, US should be used to detect intraperitoneal fluid collections, especially around the liver hilum, and dilatation of the biliary tree.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree