, Stefano Fanti1 and Lucia Zanoni1

(1)

Department of Nuclear Medicine, Universitary Hospital Sant’Orsola-Malpighi, Bologna, Italy

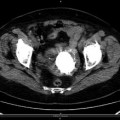

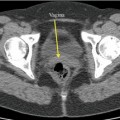

Renal Ectopia or Ectopic Kidney

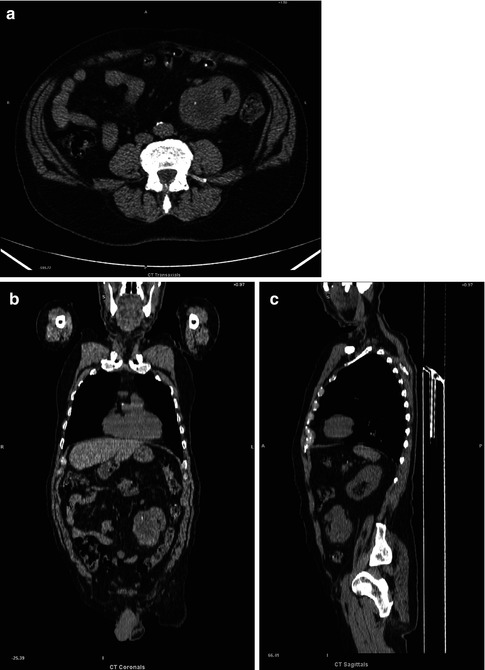

Fig. 4.1

(a–c) Ectopic right kidney in the left iliac fossa

An ectopic kidney is a birth defect in which a kidney is located below, above, or on the opposite side of its usual position. It has an incidence of approximately 1/1,000. Factors that may lead to an ectopic kidney include: poor development of a kidney bud; a defect in the kidney tissue responsible for prompting the kidney to move to its usual position; genetic abnormalities; the mother being sick or being exposed to an agent, such as a drug or chemical, that causes birth defects. An ectopic kidney may not cause any symptoms and may function normally, even though it is not in its usual position. Possible complications of an ectopic kidney include problems with urine drainage from that kidney. Abnormal urine flow and the placement of the ectopic kidney can lead to various problems such as infection, stones, kidney damage, and injury from trauma. No treatment for an ectopic kidney is needed if urinary function is normal and no blockage of the urinary tract is present. Surgery or other treatment may be needed if there is an obstruction, reflux, or extensive damage to the kidney.

Renal Stone

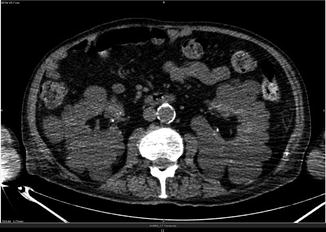

Fig. 4.2

Stone in the left renal pelvis

Renal stones are dense and attenuate strongly. For stones greater than 3 mm, non-contrast CT examinations have a reported sensitivity and specificity of 97–100 %. Both radiolucent and radiopaque stones can be identified. By utilizing computerized mapping techniques, uric acid stones with relatively low-attenuation values can be differentiated from struvite and calcium oxalate calculus stones. On the contrary CT is unable to identify very rare pure matrix stones of mucoprotein and fibrin and Crixivan stones. It is not possible to provide direct physiologic information of the degree of obstruction in patients with kidney stone.

Polycystic Kidneys

Fig. 4.3

Multiple cysts in the kidneys

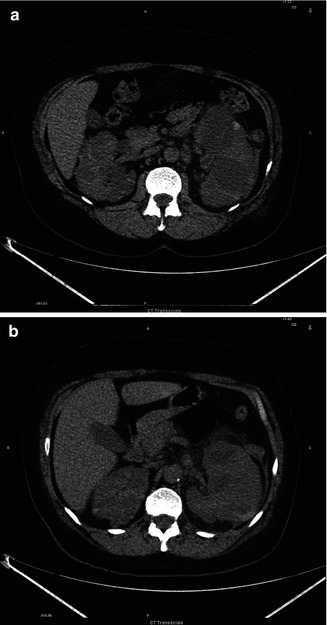

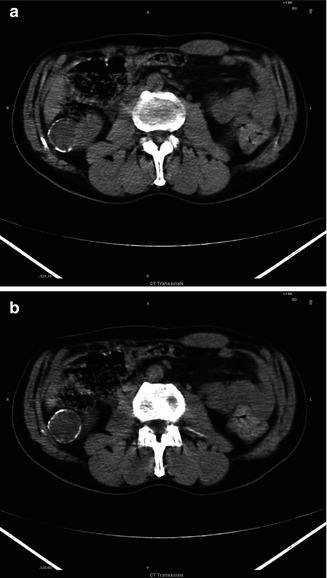

Fig. 4.4

(a, b) Polycystic kidney and left kidney inflammation

Polycystic kidney disease (PKD) is a genetic disorder characterized by the growth of numerous cysts in the kidneys. There are inherited forms of PKD: the most common autosomal dominant and the rare autosomal recessive PKD. In CT examinations we find extensive cyst in both kidneys, with a few cysts in the liver as well (in about 40 % of patients).

Bosniak Classification of Renal Cysts. The lesions in the renal parenchyma are usually divided in simple benign renal cysts and complex renal cysts. This classification is based on morphologic and enhancement characteristics with CT scanning. Category I: Benign simple cyst with a thin wall without septa, calcifications, or solid components with density of water. Category II: Benign cystic lesions in which there may be a few thin septa; the wall or septa may contain fine calcification or a short segment of slightly thickened calcification. This category also includes uniformly high attenuating lesions that are less than 3 cm in diameter, well marginated. Category IIF: These cysts, generally well marginated, may have multiple thin septa or minimal smooth thickening of the septa or wall, which may contain calcification that may also be thick and nodular. It also includes totally intrarenal high attenuating lesions that are more than 3 cm in diameter. Follow-up is requested to ascertain that they are nonmalignant. Measurable enhancement can be present in both category III and IV; therefore, ceCT would be necessary for differentiation. Category III: These are indeterminate cystic masses that have thickened irregular or smooth walls or septa. Approximately 40–60 % are malignant (cystic renal cell carcinoma and multiloculated cystic renal cell carcinoma). On the contrary hemorrhagic cysts, chronic infected cysts, and multiloculated cystic nephroma are benign. Category IV: These lesions (85–100 % are malignant) have all the characteristics of category III cysts; in addition they contain enhancing soft-tissue components that are adjacent to and independent of the wall or septum.

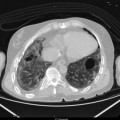

Renal Cancer

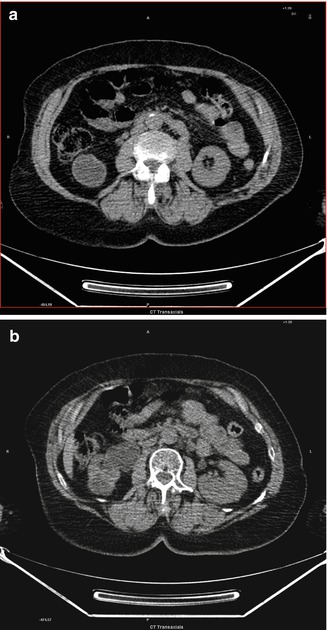

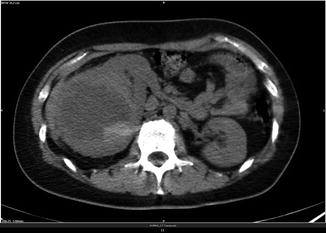

Fig. 4.5

(a, b) Hypo-attenuated mass in the right kidney

Kidney cancer originates in the kidney in two principal locations: most cancers in the renal tubule are renal cell carcinoma and clear cell adenocarcinoma; on the contrary most cancers in the renal pelvis are transitional cell carcinoma. The primary limitation of CT is the characterization of hypo-attenuation in masses smaller than 8–10 mm. On initial non-enhanced CT scans, RCCs may appear as iso-attenuating, hypo-attenuating, or hyper-attenuating relative to the remainder of the kidney. Amorphous and internal calcification (less often rim like calcifications) may be present. It may also appear as a completely solid nodule.

Oncocytoma

Fig. 4.6

(a, b) Homogeneous hypo-attenuated mass in the right kidney with aperipheral well-defined calcified rim

The imaging appearance of oncocytomas, which is a benign proximal tubular adenoma, is difficult to distinguish from malignant renal cell carcinoma. They are sharply demarcated lesions, solid cortical mass, often large at presentation. Usually if less than 3 cm they present homogeneous attenuation, if more than 3 cm heterogeneous attenuation. Perinephric fat stranding due to edema and calcifications may be present.

Lymphoma of the Kidney

Fig. 4.7

Voluminous mass in the right enlarged kidney with inhomogeneous attenuation and central necrotic changes

Typical patterns of renal lymphoma include multiple renal masses, solitary masses, diffuse infiltration, and invasion from contiguous retroperitoneal disease. Atypical CT patterns may also be encountered and provide a diagnostic challenge. These include spontaneous hemorrhage, necrosis, heterogeneous attenuation, cystic transformation, and calcification.

CT accurately depicts renal involvement in most patients; it can also most completely define the extrarenal extent of disease and provide comprehensive staging information. CT allows evaluation of the surrounding anatomic structures, including the peri-renal space and retroperitoneum, which are commonly involved by lymphoma. Lesions can be solitary masses (10–20 %) or multiple masses (60 %). They are generally bilateral and present extension by contiguity (25–30 %), diffuse infiltration (20 %), or perirenal involvement (10 %). Radiological findings frequently indicate renal involvement with multiple nodules (60 %).