Abstract

There are three abnormalities of kidney location: simple renal ectopia or pelvic kidney, crossed renal ectopia, and horseshoe kidney. Simple renal ectopia is a kidney that is located on the correct side but in the pelvis, with the adrenal gland filling the renal fossa. With crossed renal ectopia, both kidneys are on the same side; one kidney is in the normal location and the other is located just below the first, with its ureter crossing the midline before inserting into the bladder. Horseshoe kidney indicates fusion of the inferior poles of the kidneys in the midline to form a horseshoe shape. Renal ectopia tends to be more challenging to detect prenatally than other renal abnormalities, particularly horseshoe kidney. Each type of ectopia is associated with increased risk for vesicoureteral reflux and ureteropelvic junction obstruction. Third-trimester evaluation is suggested, even in the absence of renal pelvis dilatation earlier in gestation. There is also a high prevalence of anomalies of other organ systems, and if any associated anomalies are identified, amniocentesis should be offered.

Keywords

pelvic kidney, crossed renal ectopia, horseshoe kidney

Introduction

There are three types of abnormalities of renal location: simple renal ectopia (e.g., pelvic kidney), crossed renal ectopia, and horseshoe kidney. They are collectively termed renal ectopia . During normal development, the metanephros migrates from the pelvis to the abdomen, and rotates about its longitudinal axis. Abnormalities of renal location may occur because of failure of ascent of the metanephric buds or because of fusion before ascent. Although renal ectopia is relatively benign, it is associated with an increased risk of complications, including vesicoureteral reflux (VUR), ureteropelvic junction (UPJ) obstruction, infection, and renal calculi. Affected individuals are usually asymptomatic. If a prenatal diagnosis is not made, affected individuals may not receive medical attention until complications arise. Improvements in ultrasound (US) technology have made it easier to identify abnormalities of renal location; however, these anomalies are subtle, and an index of suspicion is required.

Disorder

Definition

Pelvic kidney is also called simple renal ectopia and refers to a kidney that is on the correct side but has failed to migrate upward. A pelvic kidney is located opposite the sacrum and below the aortic bifurcation.

Crossed renal ectopia occurs when both kidneys are located on the same side of the spine. In most cases, the kidney on the incorrect side is located below the normal kidney and is fused with it (termed crossed-fused ectopia ). The ureter of the displaced kidney crosses the midline and inserts into the bladder in the normal location.

Horseshoe kidney is a fusion of the lower poles of the kidneys, with an isthmus that crosses the midline, usually anterior to the great vessels, and just below the inferior mesenteric artery—preventing the horseshoe kidney from migrating upward to the normal location.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

Pelvic kidney occurs in 1 : 2000 to 1 : 3000 births. It is slightly more common in males, and a left-sided predominance has been reported. Pelvic kidney is bilateral in 12% of cases.

The prevalence of crossed renal ectopia is 1 : 7500 individuals. It is twice as common in males, and the left kidney is more often the one that is crossed, meaning that both kidneys are commonly found on the right side. In approximately 75% of cases, the kidneys are fused (i.e., crossed-fused ectopia).

Horseshoe kidney is the most common renal ectopia, with a reported prevalence of 1 : 400 individuals. It is also twice as common in males.

All forms of renal ectopia are associated with other renal abnormalities. Hydronephrosis has been reported in more than 50%; VUR and UPJ obstruction each occur in approximately 20% (see Chapter 12 ). Renal calculi have been reported in 20% of cases of horseshoe kidney, postulated to be caused by a combination of stasis and infection.

Renal ectopia is also associated with a high prevalence of anomalies of other organ systems. Reproductive tract abnormalities have been reported in approximately 25%, musculoskeletal anomalies in 25%, and cardiac malformations in 10%. Horseshoe kidney is further associated with chromosomal abnormalities, including Turner syndrome and trisomies 21, 18, and 13.

Etiology, Pathophysiology, and Embryology

During the sixth through ninth gestational weeks, the kidneys ascend from the pelvis to the lumbar region just below the adrenal glands. Failure of ascent results in renal ectopia. The mechanism behind failed ascent is unknown. Theories include ureteral bud maldevelopment, defective metanephric tissue, genetic abnormalities, vascular obstruction, and teratogen exposure. Ectopic kidneys are more likely to be hypoplastic (see Chapter 9 ), are abnormally shaped, and have an atypical blood supply. Pelvic kidney represents complete failure of ascent. Crossed renal ectopia results from abnormal migration to the opposite side of the pelvis. With crossed renal ectopia, there is malrotation of both kidneys, which may lead to narrowing at the level of the ureteropelvic junction and subsequent obstruction. The kidney that is crossed commonly fuses with the inferior pole of the normally located kidney, but there are also other variants, including kidneys that are S -shaped, L -shaped, lump-shaped, disk-shaped, and superiorly fused. In each form of crossed renal ectopia, the ureter of the kidney that is on the abnormal side crosses the pelvis to insert normally into the bladder.

Horseshoe kidney is believed to result from fusion of the metanephric buds before the renal capsule has matured. The inferior poles are joined at an isthmus that is typically located below the inferior mesenteric artery, preventing their normal medial rotation as well as ascent. The isthmus may be composed of renal tissue but is often fibrous. The cause of the fusion is unknown. Theories include close approximation of metanephric tissue in early embryogenesis, excessive renal blastema, and a teratogenic event involving abnormal migration of posterior nephrogenic cells. It is hypothesized that development of the isthmus through abnormal migration may account for the slightly increased incidence of associated renal malignancies.

In one series, 10% of parents and 5% of offspring of individuals with horseshoe kidney were also found to have renal anomalies, and 80% of these were horseshoe kidney, suggesting autosomal dominant inheritance.

Manifestations of Disease

Clinical Presentation

Prenatal diagnosis of renal ectopia is based on US findings, as discussed subsequently. These abnormalities commonly go undetected prenatally and postnatally. Children may be diagnosed during evaluation for urinary tract infection because of the association with VUR and UPJ obstruction. Some individuals with horseshoe kidney come to attention because of renal calculi.

Imaging Technique and Findings

Ultrasound.

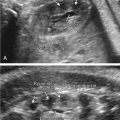

When there is a pelvic kidney or crossed renal ectopia, the initial US finding is often an inability to visualize a normal kidney in one renal fossa (see Fig. 11.1 ). If the diagnosis is suspected, it is important to image both renal fossae in multiple planes and to image the pelvis to determine whether the diagnosis is unilateral renal agenesis or renal ectopia. It is also important to assess for abnormalities of the contralateral kidney. When a kidney is not present in the renal fossa, the adrenal flattens and fills the fossa in what has been termed the “lying-down” adrenal sign (see Figs. 10.3 and 11.2 ). The adrenal gland is suprarenal and almond-shaped, with a hypoechoic cortex and hyperechoic medulla.

Pelvic kidneys are usually located below the level of the aortic bifurcation and opposite the sacrum. The pelvic kidney may be challenging to differentiate from surrounding structures, particularly in the second trimester when there is less perinephric fat. In addition, the pelvic kidney is frequently hypoplastic ( Fig. 8.1 ). Hypoplasia may be diagnosed using reference tables (see Table 9.1 ). Abnormal orientation of the renal pelvis may predispose to obstruction, and hydronephrosis is common. As shown in Figs. 8.2 and 8.3 , the degree of dilatation may range from mild to severe. With any degree of hydronephrosis, surveillance for worsening obstruction is recommended (see also Chapter 12 ).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree