Chapter Outline

Normal Radiographic Appearances

Prolapsed Esophagogastric Mucosa

The gastroesophageal junction has traditionally been a difficult area to evaluate on barium studies because the physiologic events associated with swallowing produce a dynamic, constantly changing appearance. The use of complicated, often contradictory terminology to describe normal and abnormal findings at the cardia has also been a source of confusion. Evaluation of the cardia, perhaps more than of any other area in the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract, requires meticulous attention to radiographic technique. Although rings, strictures, and hernias are best seen on conventional single-contrast barium studies, neoplastic lesions at the cardia are better delineated on double-contrast studies. Thus, radiologists must use different techniques during the fluoroscopic examination to optimally evaluate this area.

Radiographic Technique

The gastric cardia is a notoriously difficult area to examine on single-contrast barium studies. Because of the overlying rib cage, the fundus is not accessible to manual palpation or compression. If the fundus is not fully distended, crowded gastric folds may obscure surface detail in this region. If larger volumes of barium are used to distend the fundus, however, it becomes relatively opaque, so only contour abnormalities can be identified. Because of the inherent limitations of single-contrast barium studies in examining the cardia and fundus, double-contrast techniques have been used to improve radiographic visualization of this area.

The routine double-contrast esophagogram should include a double-contrast examination of the gastric cardia and fundus. After upright double-contrast views of the esophagus have been obtained, the patient should be placed in the recumbent right lateral position (i.e., right side down) to visualize the gastric cardia directly en face. The cardia should be observed for several seconds and, if it appears normal, a single spot image should be obtained. If the cardia appears abnormal, however, additional spot images should be taken as the patient is rotated farther, so that questionable lesions can be demonstrated both en face and in profile.

After the double-contrast portion of the study has been completed, the patient should be placed in the prone, right anterior oblique position and instructed to rapidly gulp a thin, low-density barium suspension to achieve optimal distention of the distal esophagus. Single-contrast technique is particularly important for evaluating possible rings, strictures, or hernias in this region because upright double-contrast views often fail to produce the degree of distention needed to optimally demonstrate these abnormalities. If necessary, a bolster may be placed beneath the patient’s upper abdomen to increase intra-abdominal pressure and improve esophageal distention. When a lower esophageal ring is detected, barium tablets or barium-impregnated marshmallows may also be used to help determine the caliber and obstructive potential of the ring and, if the tablet or marshmallow becomes impacted above the ring, to determine whether this impaction reproduces the patient’s dysphagia.

Normal Radiographic Appearances

The esophagus is a relatively nondistensible tubular structure with a saccular distal segment that communicates with the stomach. The saccular segment has been termed the phrenic ampulla or vestibule because it is the “entrance hall” to the stomach. Manometric studies have shown that the esophageal vestibule corresponds to the location of the lower esophageal sphincter, a 2- to 4-cm in length high-pressure zone just above the gastroesophageal junction that prevents reflux of acid into the esophagus. The vestibule extends inferiorly through the esophageal hiatus of the diaphragm before joining the stomach several centimeters below the hiatus. The short intra-abdominal segment of the esophagus terminates at the gastroesophageal junction or gastric cardia. The left lateral aspect of the cardia is demarcated anatomically by sling fibers that hook around a notch formed between the distal esophagus and gastric fundus (the cardiac incisura). Important anatomic structures in this region that may be recognized on barium studies include the cardia, Z line, and lower esophageal mucosal and muscular rings. These structures are discussed separately in the following sections.

Cardia

The gastric cardia is often not visualized on single-contrast barium studies because this region is obscured by barium in the fundus or by overlying gastric rugae. However, the ability to recognize the normal appearances of the cardia has improved dramatically with the use of double-contrast technique. In one study, the normal anatomic landmarks at the cardia were seen on more than 95% of double-contrast examinations but on only 20% of single-contrast examinations. Thus, double-contrast technique is essential for evaluating this area.

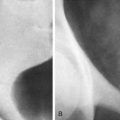

The radiographic appearance of the cardia on double-contrast studies depends on how firmly it is anchored by the surrounding phrenoesophageal membrane to the esophageal hiatus of the diaphragm. When the cardia is well anchored, protrusion of the distal esophagus into the fundus produces a circular elevation containing three or four stellate folds that radiate to a central point at the gastroesophageal junction, also known as the cardiac rosette ( Fig. 26-1A ). This elevation is demarcated from the adjacent fundus by a curved hooding fold that surrounds it laterally and superiorly. Several longitudinal folds are usually seen extending inferiorly from the cardiac rosette along the posterior wall of the lesser curvature. However, it should be recognized that the cardiac rosette reflects the closed resting state of the lower esophageal sphincter, so this normal anatomic landmark will be transiently obliterated by relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter during deglutition.

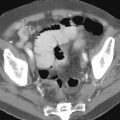

When the cardia is less firmly anchored to the surrounding phrenoesophageal membrane, the cardiac rosette may be visible without an associated protrusion or circular elevation ( Fig. 26-1B ). With further ligamentous laxity, the rosette itself may vanish and the cardia may be characterized by only a single undulant or crescentic line that traverses the region of the esophageal orifice ( Fig. 26-1C ). Finally, severe ligamentous laxity may lead to the formation of an axial hiatal hernia, so no cardiac structure is identified below the diaphragm. Instead, gastric folds may converge superiorly to a point several centimeters above the esophageal hiatus ( Fig. 26-1D ). This finding should therefore suggest an axial hiatal hernia, and a single-contrast esophagogram should be obtained with the patient in a prone position to confirm the presence of a hernia.

Radiologists should be familiar with the various radiographic appearances of the cardia, because malignant tumors involving the cardia may be recognized only by distortion or obliteration of these normal anatomic landmarks (see later, “ Carcinoma of the Cardia ”).

Z Line

The Z line is an irregular serrated line that demarcates the squamocolumnar mucosal junction. The Z line can sometimes be recognized on double-contrast esophagograms as a thin radiolucent stripe in the distal esophagus with a characteristic zigzag appearance ( Fig. 26-2 ). Occasionally, the Z line can be mistaken for superficial ulceration associated with reflux esophagitis, particularly if the esophagus is not completely distended. Because the Z line represents the histologic squamocolumnar junction, it is usually located at or near the gastroesophageal junction.

Mucosal Ring

A lower esophageal mucosal ring is the most common ringlike narrowing found in the distal esophagus. The ring consists of a membranous ridge covered by squamous epithelium superiorly and columnar epithelium inferiorly, so it corresponds histologically to the squamocolumnar junction. This mucosal ring, also known as a B ring, is manifested on barium studies by a thin, weblike area of narrowing at the gastroesophageal junction ( Fig. 26-3 ). The ring has smooth, symmetric margins and a height of 2 to 4 mm. Mucosal rings with a diameter more than 20 mm rarely cause symptoms. If the diameter of the ring is less than 20 mm, however, it may cause dysphagia and might therefore represent a pathologic finding (see later, “ Schatzki Ring ”).

Lower esophageal mucosal rings are fixed, reproducible structures on barium studies, but the distal esophagus must be adequately distended to visualize these structures. Single-contrast technique with the patient in a prone, right anterior oblique position is particularly well suited for demonstrating lower esophageal rings because it is the best technique for achieving optimal distention of the distal esophagus. It has been shown that more than 50% of lower esophageal rings seen on prone single-contrast views of the esophagus are not visualized on the double-contrast phase of the examination. Thus, biphasic studies are required to demonstrate these structures.

Muscular Ring

A muscular or contractile ring, also known as an A ring, is a much less common finding in the distal esophagus than a mucosal ring (B ring). Muscular rings are located at the proximal end of the esophageal vestibule near the tubulovestibular junction and are completely covered by squamous epithelium. Unlike a mucosal ring, which is a fixed anatomic structure, a muscular ring occurs as a transient physiologic phenomenon resulting from active muscular contraction in the distal esophagus in the region of the lower esophageal sphincter.

A muscular ring usually appears on esophagography as a relatively broad, smooth area of tapered narrowing that changes considerably in caliber and configuration during the fluoroscopic examination (see Fig. 26-3 ). Because a muscular ring is caused by active muscular contraction, it may vanish completely with esophageal distention, so it is observed as a transient finding at fluoroscopy. Not infrequently, mucosal and muscular rings are visible during the same examination (see Fig. 26-3 ). In such cases, the fixed nature of the mucosal ring readily distinguishes this structure from the changing appearance of the muscular ring above.

Schatzki Ring

Although some investigators have used the terms Schatzki ring and lower esophageal ring interchangeably, Schatzki himself originally described this entity as a pathologically stenotic ring that caused dysphagia. Because most lower esophageal rings do not cause symptoms, they probably should not be called Schatzki rings. Instead, the term should be reserved for symptomatic patients with narrow-caliber rings at the gastroesophageal junction. Thus, the diagnosis of a Schatzki ring is made on the basis of the clinical and radiographic findings.

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of a Schatzki ring is uncertain. Some investigators favor a congenital origin, but the rarity of symptoms before 50 years of age tends to refute this theory. Other investigators believe that a Schatzki ring represents an annular, ringlike stricture caused by scarring from reflux esophagitis. This theory is supported by one study showing that Schatzki rings undergo transformation into true, reflux-induced (peptic) strictures on serial barium studies. Nevertheless, it is difficult to explain the frequent absence of reflux symptoms in these patients, so the data are inconclusive.

Clinical Findings

Schatzki rings are typically manifested by episodic dysphagia for solids. In a study of 332 patients, Schatzki found that lower esophageal rings less than 13 mm in diameter almost always caused dysphagia, whereas rings more than 20 mm in diameter almost never caused dysphagia. A statistical analysis of Schatzki’s original data 40 years later showed that a 1-mm decrease in ring diameter corresponded to a 46% increase in the likelihood that a patient has dysphagia.

Patients with Schatzki rings typically present with episodic dysphagia for solids, sometimes remaining asymptomatic until a large bolus of food lodges above the ring. Because the most frequent offending agent is an inadequately chewed piece of meat, this condition has been described as the steak house syndrome . The impacted bolus in the distal esophagus may cause severe chest pain or an uncomfortable sticking sensation behind the lower sternum. Resolution of symptoms almost always occurs when the impacted bolus is passed, regurgitated, or removed. Rarely, a prolonged bolus obstruction may lead to esophageal perforation.

Relief from symptoms is sometimes obtained by advising these individuals to eat more slowly and chew their food more carefully. However, some patients with recurrent dysphagia require mechanical disruption or dilation of the ring or, rarely, surgery.

Radiographic Findings

A Schatzki ring usually appears on barium studies as a thin (2 to 4 mm in height), weblike constriction (<13 mm in diameter) at the gastroesophageal junction ( Fig. 26-4 ). A hiatal hernia is almost always observed below the level of the ring. Except for its smaller caliber, a Schatzki ring therefore has the same appearance and location as an asymptomatic mucosal ring. Almost all rings less than 13 mm in diameter cause dysphagia, so they may be classified as Schatzki rings on the basis of the radiographic findings. Occasionally, however, rings between 13 and 20 mm may also cause symptoms, so the diagnosis of a Schatzki ring in these patients requires some knowledge of the clinical history.

Like other rings in the lower esophagus, Schatzki rings are visualized on barium studies only if the lumen above and below the ring is distended beyond the caliber of the ring. As a result, single-contrast views of the distal esophagus with the patient prone (optimizing distention of the distal esophagus) may demonstrate Schatzki rings that are not visible, even in retrospect, on the double-contrast phase of the examination because of inadequate distention of this region ( Fig. 26-5 ). Conversely, overdistention of a hiatal hernia on prone views can result in overlap of the distal end of the esophagus and proximal end of the hernia, producing a double density of two superimposed, convex collections of barium that obscures the region of the gastroesophageal junction and prevents visualization even of high-grade Schatzki rings ( Fig. 26-6A ). When this overlap phenomenon occurs, additional prone views of the distal esophagus should be obtained when the hiatal hernia is less distended to avoid overlap of the hernia and adjacent distal esophagus, enabling visualization of these rings ( Fig. 26-6B ). If a lower esophageal ring still cannot be detected because of persistent overlap in patients with clinical symptoms of a ring, the patient should be instructed to swallow a barium tablet; if the tablet lodges at the gastroesophageal junction, a Schatzki ring should be strongly suspected, and the patient should undergo endoscopy for further evaluation and a possible dilation procedure. With optimal technique, biphasic esophagography is thought to be even more sensitive than endoscopy for detecting Schatzki rings.