11 Spinal Accessory Nerve

Functions

• Special visceral efferent (SVE). Branchial motor to sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles.

Anatomy

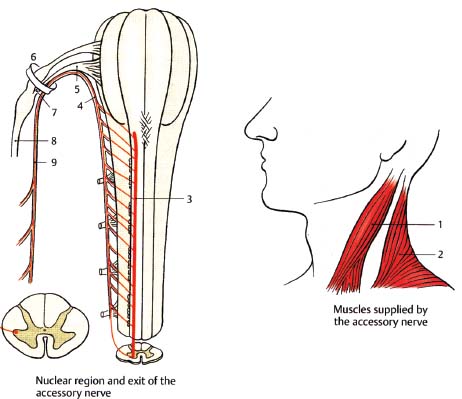

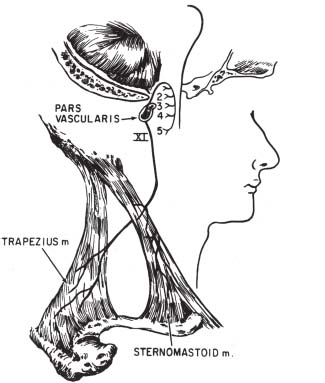

• The spinal accessory nerve arises from the cervical spinal cord (levels C-1–5) from a column of ventral horn cells that together are called the accessory nucleus (Fig. 11.1). The spinal accessory rootlets exit the cervical cord and unite to form a single spinal root that ascends posterior to the dentate ligament, enters the cranium via the foramen magnum, and then exits the cranium through the pars vascularis of the jugular foramen. The accessory nerve then descends obliquely in the carotid space between the internal carotid artery (ICA) and the internal jugular vein (IJV), across the anterior surface of the atlantal transverse process posterior to the stylohyoid and digastric muscles, to enter the deep aspect of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, which it penetrates and supplies. Emerging lateral to the sternocleidomastoid muscle in close proximity to the great auricular nerve (sensory branch of cervical plexus from C-2/C-3), it crosses the posterior cervical triangle (the most common site of iatrogenic injury) on the surface of the levator scapulae muscle to end in and supply the trapezius muscle (Fig. 11.2). The posterior cervical triangle is formed by the anterosuperior border of the trapezius muscle, the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, and the middle third of the clavicle.

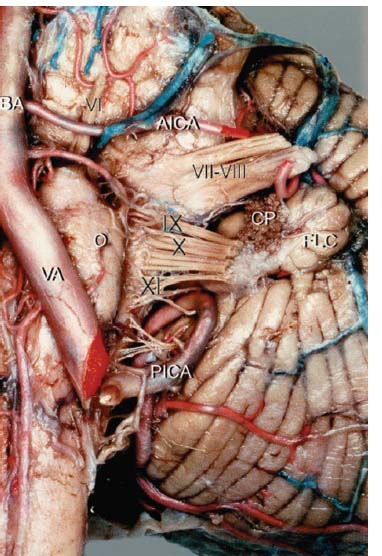

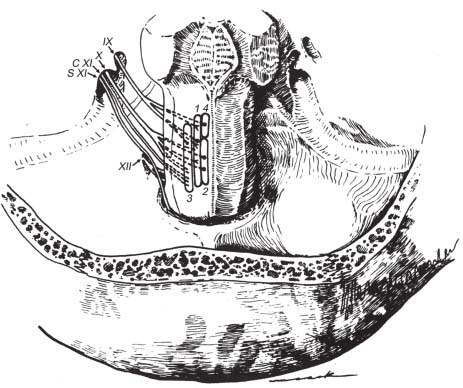

• The so-called cranial root of the accessory nerve has been described as a group of fibers that arise from the caudal portion of the nucleus ambiguus (the more cranial portions of which also supply branchial motor innervation to cranial nerves [CNs] IX and X), and emerge from the medulla as several rootlets in the postolivary sulcus (Fig. 11.3). Along with the vagus nerve proper, the cranial root runs laterally in the cerebellomedullary cistern and passes through the pars vascularis of the jugular foramen (Fig. 11.4). At the level of the superior vagal (jugular) ganglion, fibers from the cranial root blend into the vagus nerve and are distributed with the pharyngeal and superior laryngeal branches of CN X to supply the pharynx and larynx. Therefore, it is best to consider the cranial root of the accessory nerve as a part of the vagus nerve and functionally completely separate from the spinal accessory nerve.

• The sternocleidomastoid muscle consists of two divisions (sternomastoid and cleidomastoid). The sternomastoid (from sternum to mastoid) acts mainly on the atlantoaxial joint to rotate the head toward the contralateral side. The cleidomastoid (from clavicle to mastoid) primarily acts on the cervical joints to tilt the head downward. When the sternocleidomastoid as a whole contracts, the head is drawn toward the ipsilateral shoulder and turned toward the contralateral side. Simultaneous bilateral sternocleidomastoid muscle contraction flexes the head.

• The trapezius muscle retracts the head and also elevates, rotates, and retracts the scapula.

Fig. 11.1 Spinal accessory nerve, spinal root: spinal nuclear region and root exit. (1, sternocleidomastoid muscle; 2, trapezius muscle; 3, spinal nucleus of the accessory nerve; 4, spinal root; 5, cranial root; 6, jugular foramen; 7, internal branches to vagus nerve; 8, vagus nerve; 9, accessory nerve.)

Fig. 11.2 Spinal accessory nerve: distal branches. The spinal accessory nerve receives fibers from cervical levels 1 through 5, ascends through the foramen magnum, and exits the skull base via the pars vascularis of the jugular foramen. Extracranial branches supply branchial motor innervation to the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles. (From Harnsberger HR. Handbook of Head and Neck Imaging (2nd ed.) St. Louis, MO: Mosby, 1995. Modified with permission.)

Fig. 11.3 Anterior view of the left cerebellopontine angle, demonstrating the origin of the cranial root of CN XI at the postolivary sulcus of the medulla. Note its position just inferior to the rootlets of CN X. (AICA, anterior inferior cerebellar artery; PICA, posterior-inferior cerebellar artery; BA, basilar artery; CP, choroid plexus; FLC, flocculus; O, olive; VA, vertebral artery; VI–VII, facial and vestibulocochlear nerves; IX, glossopharyngeal nerve; X: vagus nerve.) (From Ozveren MF, Ture U, Ozek MM, et al. Anatomic landmarks of the glossopharyngeal nerve: a microsurgical anatomic study. Neurosurgery 2003;52:1400-1410. Reprinted with permission.)

Fig. 11.4 Nuclear origins and cisternal courses of glossopharyngeal, vagus, and spinal accessory nerves. Note that the glossopharyngeal nerve traverses the more anterior part of the jugular foramen (pars nervosa), whereas the vagus and spinal accessory nerves pass through the posterior part (pars vascularis). The hypoglossal nerve is shown exiting through the more inferiorly located hypoglossal canal. (1, nucleus solitarius; 2, dorsal motor nucleus of CN X; 3, nucleus ambiguus; 4, superior salivatory nucleus; C XI, cranial root of CN XI; S XI, spinal root of CN XI.) (From Harnsberger HR. Handbook of Head and Neck Imaging (2nd ed.) St. Louis, MO: Mosby, 1995. Reprinted with permission.)

Spinal Accessory Nerve Lesions

Evaluation

• Motor evaluation. Injury to the spinal accessory nerve results in paresis and/or atrophy of the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles.

Sternocleidomastoid paresis. Manifests as weakness in turning the head to the opposite side. Test by observing with inspection and palpation while having the patient rotate the head against resistance. Bilateral sternocleidomastoid paresis results in weak neck flexion.

Sternocleidomastoid paresis. Manifests as weakness in turning the head to the opposite side. Test by observing with inspection and palpation while having the patient rotate the head against resistance. Bilateral sternocleidomastoid paresis results in weak neck flexion.

Trapezius paresis. Manifests as shoulder drop, difficulty raising abducted arm above horizontal. Test by observing with inspection and palpation while having the patient shrug the shoulders against resistance. Bilateral trapezius paresis results in weak neck extension. Because of partial innervation of the trapezius from the cervical plexus, lower trapezius function may be spared in pure accessory palsies.

Trapezius paresis. Manifests as shoulder drop, difficulty raising abducted arm above horizontal. Test by observing with inspection and palpation while having the patient shrug the shoulders against resistance. Bilateral trapezius paresis results in weak neck extension. Because of partial innervation of the trapezius from the cervical plexus, lower trapezius function may be spared in pure accessory palsies.

Types

Supranuclear Lesions

• In hemispheric lesions resulting in contralateral hemiplegia, the trapezius muscle contralateral to the lesion is paretic (manifesting as contralateral weakness of shoulder elevation). In contrast, the head is always turned away from the plegic side (toward the lesion), indicating paresis of the sternocleidomastoid muscle ipsilateral to the lesion. How can this be explained? It is a neuroanatomical pearl that the sternocleidomastoid is controlled by the ipsilateral motor cortex, possibly via a rare double decussation (ipsilateral cortex to contralateral pons to ipsilateral cervical cord). This theory is also supported by the observation that hemispheric seizure foci cause contraction of the ipsilateral sternocleidomastoid and cause ictal head deviation away from the side of the seizure. Thus the patient looks away from the lesion with seizures, and toward the lesion with stroke.

Nuclear Lesions

• Rarely cause CN XI palsy in isolation

• High cervical cord or low medullary lesions (e.g., brainstem infarction, brainstem tumor, syringomyelia/syringobulbia)

Foramen Magnum/Jugular Foramen Lesions (Table 11.1)

• Generally also involve adjacent CNs (IX, X, XII) and/or long tracts

• Neoplasms (e.g., glomus tumors, schwannomas, meningiomas)

• Trauma

Extracranial Lesions

• Isolated CN XI palsy may occur at the level of the neck with the following:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree