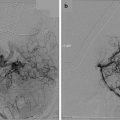

Fig. 24.1

(a) A 5 cm acoustic neuroma prior to resection. The patient presented with tinnitus, hearing loss, and signs of brainstem compression. (b) Postoperative image after a retrosigmoid craniotomy. All preoperative symptoms resolved

A retrospective review of our institution’s last 50 cases of retrosigmoid resections was compared to the last 50 translabyrinthine resections. Tumors were included that were 3 cm or less and results were categorized in terms of facial nerve outcome, incidence of total resection, and major complications. At discharge, 37 of the retrosigmoid patients had an H-B score of 1 as compared to 28 of the translabyrinthine patients. Combining H-B 1 and 2 scores showed 82 % with the retrosigmoid cases and 70 % of the translabyrinthine. This did not reach statistical significance. There was one major neurological complication in the retrosigmoid group and none in the other group. Three cases of subtotal removal resided in each group. Long-term follow-up of these patients showed even less of a difference in facial nerve function. This suggests that surgical technique may be more important than approach strategies in terms of outcome for acoustic tumors.

Ideally, each practitioner should have a working knowledge of all approaches. This can instill the wary patient with some confidence that decision-making is based on assessment of the patient’s best interests. For those who are experiencing unacceptable results, altering approach strategy may show modest benefits, but doing such will not make up for deficiencies in surgical technique as it relates to the brainstem vascularity and cranial nerves.

Choice of Treatment Method (Radiosurgery Versus Excision)

At our institution, the three traditional approaches for surgical excision of acoustic tumors are practiced. Further, additional technologies for radiosurgery (such as Gamma Knife, Linac, Cyberknife, etc.) are offered. The surgical decision-making is less predicated on available technologies or reliance on a practiced single surgical approach, than it is on patient age, tumor size, and need for hearing preservation (Table 24.2).

Age and Tumor Size

For younger patients, emphasis is placed on surgical removal. A surveillance strategy in this group is likely to be futile, since inevitably the lesion will cause further symptoms and require treatment. Radiosurgery has a long follow-up period and the window of vulnerability for recurrence is potentially wide. Reliable data on lifelong tumor control for patients in their 30s or 40s is lacking. For those in their 50s and 60s, single fraction radiosurgery is an attractive alternative. Efficacy and safety statistics are available for this group and are highly acceptable (Fig. 24.2). Patients in older age groups rarely need any therapy unless their tumor is large enough to be threatening [11, 12]. Furthermore, radiosurgery is not without its complications and failures, which develop in approximately 3–34 % of cases in even the most experienced centers [44, 45]. Serviceable hearing is lost in 30–43 % of patients following radiosurgery [46, 47]. Finally, in the event that surgical excision is required following radiosurgery, it has been reported that tumor excision is much more challenging, and the resiliency of the facial nerve is compromised, compared to nonirradiated patients [48].

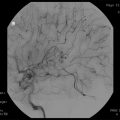

Fig. 24.2

(a) A 2.5 cm acoustic neuroma in a patient who presented with slight hearing loss. The fourth ventricle is distorted. This patient elected to have radiosurgery. (b) Post gamma knife radiosurgical treatment. Central necrosis is present as well as decreased pressure on posterior fossa structures

Table 24-2.

Treatment modality.

Radiosurgery | Surgery | Observe | |

|---|---|---|---|

Size | |||

>2.5 cm | + | +++ | 0 |

1.5 to 2.5 cm | ++ | ++ | + |

<1.5 cm | +++ | ++ | ++ |

Age | |||

<40 | + | +++ | 0 |

40 to 60 | ++ | ++ | + |

>60 | +++ | + | +++ |

Hearing | |||

>50/50 | +++ | ++ | ++ |

<50/50 | ++ | ++ | + |

Recurrent | +++ | + | + |

For large lesions greater than 3 cm, single fraction radiosurgery has no role [49]. For these lesions, gross surgical removal or in certain situations subtotal removal, with follow-up radiosurgery or observation, is advisable. Subtotal removal for a patient with a single tumor and good hearing in the other ear should be an unusual event. A small residual may be left behind in an effort to avoid a major complication such as facial nerve sacrifice or brainstem injury. For younger patients with large tumors, surgical removal is the preferred strategy. The length of vulnerability for recurrence is too great for younger patients to rely on subtotal removal. Some further therapeutic endeavor will ultimately be necessary, multiplying the potential for complications.

Large lesions in older patients can present some strategic problems. This would seem like an ideal situation for hypofractionated radiosurgery. However, with lesions greater than 4 cm or somewhat smaller lesions with associated arachnoid cysts usurping much of the available reserve in the posterior fossa, radiosurgery with its attendant edema formation may produce unacceptable risks 6–12 months posttreatment. Data is sorely lacking for this modality in larger tumors. Until better long-term studies are available, older patients in good health with large lesions should be offered the option of surgical removal. The decision for total versus subtotal removal is made at the time of surgery and predicated on the likelihood of complications. Radiosurgery as an adjunct can be offered for any threatening residual. For large tumors in older patients who are poor surgical risks, hypofractionated radiosurgery is a logical option.

Hearing Preservation

Hearing preservation in the context of surgical removal can be expected in experienced hands to be successful 50 % of the time with intracanalicular tumors and 30 % with larger lesions that are generally under 3 cm. This presupposes good functional hearing to begin with. Attempts to save hearing in a marginal or poorly hearing ear will be unrewarding. That ear will be a constant source of distraction to the patient as it picks up unstructured background noise and reduces the overall functionality of the hearing. Thus, compromises in surgical strategy to preserve the function of a poorly hearing ear should be vigorously resisted.

Single fraction radiosurgery is fast growing in popularity and may become the treatment of choice in the absence of an experienced surgeon with a proven track record for the safe and effective removal. For those lesions less than 3 cm, one can expect at least 50 % hearing preservation or better assuming accepted proven radiosurgical techniques are utilized. The major drawback in prescribing it for all small acoustic tumors is the lack of long-term efficacy data. For many patients, the need for continued surveillance and the thought of the continued presence of the lesion are negative satisfiers.

If an acoustic neuroma recurs and is deemed in need of treatment, the first option should be radiosurgery. This assumes the tumor regrowth has been detected before it has grown too large for radiosurgery. In these cases a translabyrinthine surgical approach will offer the largest corridor while minimize the need for retraction or dissection of previously scarred brain. A repeat retrosigmoid craniotomy may prove difficult.

Choice of Surgical Approach

Our preference is to use the translabyrinthine approach for all tumors where hearing preservation is unlikely (Table 24.1). Thus, it is used in all large tumors and those with poor hearing. Certainly those greater than 3 cm would be treated this way and most with speech discrimination scores of less than 50 %. The only time we would favor a retro sigmoid approach in a large tumor would be the case of a large lesion in an only hearing ear where a subtotal removal is contemplated.

Table 24.1

Approach selection.

Retrosigmoid | Middle fossa | Translabyrinthine | |

|---|---|---|---|

Size | |||

<1 cm | |||

Lateral impact | + | +++ | ++ |

Medial | +++ | +++ | ++ |

<2.5 cm | +++ | 0 | +++ |

>2.5 cm | ++ | 0 | + |

Only-hearing ear | +++ | 0 | + |

Hearing | |||

>50/50 | +++ | +++ | + |

<50/50 | + | + | +++ |

Recurrent | + | 0 | +++ |

In tumors that protrude from the porus acousticus, the retrosigmoid approach is preferred for hearing preservation (Fig. 24.3). In our most recent 80 cases using this approach, functional hearing resulted in 30 %. We limit the use of the middle fossa strategy for those small intracanalicular lesions that are impacted in the lateral end of the internal auditory canal.

Fig. 24.3

(a) Intraoperative view of acoustic neuroma during a left retrosigmoid craniotomy. (b) After tumor removal, the nerves of the porus acousticus are seen. Note to transected superior vestibular nerve from where the tumor originated

Other factors come into play as patients try to make informed decisions. Socioeconomic and educational status may complicate decision making in patients who cannot understand a complex set of options. Patient and family biases for or against surgery or radiation may direct the patient’s thinking contrary to the physician’s best judgment. Access to the internet, influence from patients who have had one form of therapy or another, and loyalty to a particular institution may be relevant factors in decision-making.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree