Abstract

Ambiguous genitalia is a morphologic diagnosis, with various underlying genetic and hormonal etiologies. Because of the complex genetic, hormonal, physical, and social factors involved, determination of fetal sex in cases of ambiguous genitalia is best done postnatally, incorporating an array of clinical consultants. Congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) is the most common cause of ambiguous genitalia; timely diagnosis in the postnatal period is important because of the life-threatening consequences of the classic salt-wasting form. In cases of ambiguous genitalia, invasive diagnosis with chorionic villus sampling (CVS) or amniocentesis can be helpful in reconciling ultrasound (US) findings, determining genetic sex, and diagnosing CAH. Karyotypic results do not always determine sex assignment, given the complex hormonal and social issues involved in sex determination.

Keywords

congenital adrenal hyperplasia, disorders of sex development, clitoromegaly, bifid scrotum, labial swelling

Introduction

While not of primary focus for the medically minded sonographer or sonologist, sex determination is often the most important question for parents during a fetal ultrasound (US) examination. Sex determination, however, can be medically important in the diagnosis of zygosity or chorionicity in multiple gestations, for counseling regarding X-linked diseases, and in cases of ambiguous genitalia. The diagnosis of ambiguous genitalia, which has various causes, can be confusing for any specialist. Uncertainty in the ability to assign a fetal sex can be traumatizing for parents. Attention in explaining and investigating the findings and the differential diagnosis is critical. For both medical and psychologic reasons, ambiguous genitalia in a newborn requires timely diagnosis and management.

Disease

Definition

Ambiguous genitalia, a subclassification of the disorders of sex development (DSDs), is defined as the unclear appearance of the fetal external genitalia, leading to unsuccessful phenotypic determination of fetal sex. In essence, there is confusion between the presence of a clitoris or penis and between the presence of a scrotum or labia. DSDs are divided into five classifications according to the Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine Society and the European Society for Pediatric Endocrinology ( Table 18.1 ); ambiguous genitalia can fall within any of these classes. Other terms used to describe these disorders are intersex conditions and genital anomalies . Ambiguous genitalia is a physical or morphologic diagnosis because there are many different underlying causes.

| Old Nomenclature | Description | Common Examples | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 46,XY DSD | Male pseudohermaphrodite | Ambiguous or female genitalia, male gonads | Androgen insensitivity, 5α-reductase deficiency, Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome |

| 46,XX DSD | Female pseudohermaphrodite | Ambiguous or male genitalia, female gonads | Congenital adrenal hyperplasia, maternal ovarian or adrenal tumor, placental P450 aromatase deficiency |

| Ovotesticular DSD | True hermaphrodite | Ambiguous genitalia, male and female gonads | Chimeric, mixed gonadal dysgenesis |

| 46,XX testicular DSD | XX male | Ambiguous or male genitalia, male gonads | Sex-determining-region (SRY) translocation |

| 46,XY complete gonadal dysgenesis | XY sex reversal | Female genitalia, undeveloped (“streak”) gonads | Swyer syndrome |

Prevalence and Epidemiology

Abnormalities of the external genitalia that warrant further workup occur in 1 : 4500 births. The frequency of the most common cause of ambiguous genitalia, classic congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), is estimated to be 1 : 15,000.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

The external genitalia become differentiated at approximately 9 weeks of gestation, and genital development is typically complete by 12 weeks for females and 14 to 16 weeks for males. Successful morphogenesis of the external genitalia depends on dihydrotestosterone (DHT) exposure for males; in females, vulvar and vaginal differentiation is not hormone-dependent. Without DHT action (because of either a lack of DHT or a failure of DHT to function), a 46,XY fetus could have phenotypically female external genitalia. On the other hand, androgen exposure before 12 weeks’ gestation can cause labial fusion or a virilized urogenital sinus, whereas exposure after 12 weeks typically causes only clitoromegaly and labial enlargement (scrotalization). Androgen exposure may occur from maternal ingestion, maternal or fetal ovarian or adrenal tumors, or placental P450 aromatase deficiency. The last-mentioned condition can cause virilization of a female fetus by not allowing circulating fetal androgens to be converted to estrogens.

The most common cause of ambiguous genitalia is CAH. CAH is a 46,XX DSD (masculinization of a female fetus) caused by an enzymatic deficiency that disrupts steroidogenesis. In 90% of cases, the deficiency is in CYP21 (21-hydroxylase), which causes an excess of 17-hydroxyprogesterone. Excess 17-hydroxyprogesterone is shunted toward the androgen production pathway of steroidogenesis; this androgenization causes virilization of the female. Male genitalia are unaffected with the exception of possible hyperpigmentation and penile enlargement. The shunt also reduces aldosterone and cortisol production, which can produce life-threatening salt-wasting (hyponatremia and hyperkalemia) in the neonatal period. Nonclassic forms of CAH also exist, which generally cause androgenizing features only in adolescent girls or women. The presence of classic and nonclassic forms of CAH can make counseling patients who are affected or are carriers difficult; experienced specialists generally should counsel such patients.

Other causes of ambiguous genitalia include the various DSDs (see Table 18.1 ), aneuploidy (especially trisomy 13), triploidy, Prader-Willi syndrome, velocardiofacial syndrome, and Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome. More complete reviews of the various causes are available.

Manifestations of Disease

Clinical Presentation

Ambiguous genitalia is often diagnosed postnatally, although prenatal diagnosis arises when sex cannot be determined on anatomic US examination. A discrepancy between genotype (from chorionic villus sampling [CVS] or amniocentesis, or from that predicted from fetal cell-free DNA [cfDNA] screening) and phenotype (from US) often initiates an investigation to consider a fetal genital anomaly. The use of fetal cfDNA testing may make the prenatal diagnosis of ambiguous genitalia more common, as there are more opportunities to note discrepancies between karyotype and phenotype, such as an enlarged clitoris and labia in a pregnancy where cfDNA suggested a male fetus. At present, data are not available to describe a clear role for cfDNA testing in pregnancies with ambiguous genitalia beyond case reports. For instance, androgen insensitivity syndrome was diagnosed after a female phenotype was identified at the detailed anatomic screen, in a woman of advanced maternal age who had cfDNA screening that revealed the presence of a Y chromosome.

Imaging Technique and Findings

Ultrasound.

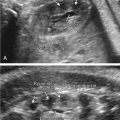

Normal female genitalia are characterized by two echogenic parallel lines in a transverse section in the midtrimester. A clitoris may be seen between these labia and should be directed caudally. The uterus occasionally can be seen in the second half of gestation as a mass between the bladder and rectum, but its absence is an unreliable indicator for sex determination. Normal male genitalia are characterized by the presence of a scrotum, which may not be seen prominently until the third trimester when testicular descent occurs. The phallus is usually seen pointing cranially. Color Doppler can be used to see urine streaming from the tip of the penis. Nomograms for scrotal diameter, penile length, and bilabial diameter have been published.

By definition, ambiguous genitalia is shown when the aforementioned signs are mixed or not identified. Specifically, ambiguous genitalia is often seen as a short phallus (or, conversely, clitoromegaly) with bifid scrotum (or, conversely, labial swelling) ( Figs. 18.1 and 18.2 ). Because of confusion, US fetal sex determination generally should not be attempted before the second trimester. In a case where ambiguous genitalia is considered, imaging in the late second and early third trimesters can allow for assessment of testes descent or the internal reproductive organs (e.g., uterus).