Chapter Outline

General Preparation of the Patient

Splenic Arterial Interventions

Embolization in Splenic Trauma

Embolization in Portal Hypertension

Embolization of Splenic Artery Aneurysms or Pseudoaneurysms

Embolization in Splenic Arterial Steal Syndrome

Interventions in the spleen have not been performed widely because of the perceived increased risk of complications, especially bleeding. A widely prevailing notion is that splenic interventions result in increased morbidity from hemorrhagic complications. This perception partly stems from the fact that splenic interventions are performed infrequently compared with interventions in other abdominal viscera, and if a more accessible lesion is present in another organ, most operators prefer to sample the other lesion rather than the splenic lesion. However, with increased familiarity with these procedures and availability of finer needles, we are now able to perform these procedures more safely and confidently.

The literature reveals that the rates of complications are much lower than anticipated. In fact, mortality is much more common from liver and pancreatic interventional procedures than from splenic interventions, probably because of the higher number of liver and pancreatic procedures performed. The success rate is 91% for splenic biopsy, 100% for splenic fluid aspiration, and 86% for splenic fluid drainage. These high success rates have been the prime impetus for widespread acceptance of splenic interventions in clinical practice.

This chapter covers the entire spectrum of splenic interventions with focus on image-guided biopsy, catheter drainage, alcohol ablation of cysts, radiofrequency ablation (RFA), and splenic artery embolization.

General Preparation of the Patient

Splenic interventions need no special prerequisite or preparation, and the general guidelines for interventions in the other abdominal viscera apply. However, a more meticulous attention may be given to the clotting and coagulation parameters, and the following laboratory values are generally recommended: platelet count higher than 50,000/µL; international normalized ratio below 1.2; and activated partial thromboplastin time, 20 to 33 seconds.

The patients are instructed to fast either overnight or for 8 hours, as applicable. The procedures are usually performed under conscious sedation with midazolam or fentanyl for adults. Typically, 1% lidocaine local anesthetic is injected in the skin and abdominal wall. However, pediatric patients may require general anesthesia with dedicated support by the pediatric anesthetic team. Securing an intravenous access before the procedure is considered mandatory.

The patients are monitored for 3 hours after the percutaneous procedure. Regular monitoring of blood pressure and pulse rate is advisable. We monitor the vital signs every 15 minutes for the first hour and every 30 minutes for the next 2 hours. Patients who remain stable in the observation period with no or only minimal discomfort can be discharged home. The patients are instructed to avoid significant physical exertion and lifting of heavy weights for at least 3 days.

Image-Guided Biopsy

The central theme of biopsy is to obtain tissue diagnosis by minimally invasive means to preclude the need for unnecessary splenectomy. Thus, the prime candidates for biopsy are patients with an indeterminate solid or cystic lesion in whom a definitive diagnosis cannot be established after clinicoradiologic correlation. The most common clinical scenarios requiring biopsy of a focal splenic lesion include patients with a known extrasplenic neoplasm and patients with known or suspected lymphoma.

Depending on the lesion, either computed tomography (CT) or ultrasound (US) guidance can be used. The choice also depends on the comfort level of the radiologist and the visibility of the lesions by either modality. In general, US is the preferred modality because of real-time guidance and quicker access. Moreover, Doppler US can also be performed before and during the biopsy to detect and to avoid large hilar vessels.

General aseptic and guiding principles apply for image-guided biopsy procedures. The biopsy sample is taken in suspended respiration. The most peripheral lesions are preferably sampled to allow a shorter parenchymal needle track and to avoid inadvertent injury to the hilar vasculature. Biopsy is done from the periphery of the lesion to decrease the possibility of obtaining necrotic material from the center. Lesions near the dome of the diaphragm need real-time US guidance or gantry tilt CT technique to avoid puncture of the pleura. US or CT is usually performed at the end of the procedure to rule out hematoma formation.

One of the more controversial areas in splenic lesion biopsy is the size of the needle used. In general, the sizes range from 18- to 22-gauge for core biopsy and 20- to 23-gauge for fine-needle aspiration ( Figs. 103-1 and 103-2 ). Core needle biopsy has an approximately 88% or better sensitivity in making a diagnosis in varying studies in the literature. The success rates, however, are lower with fine-needle aspiration procedures. A spinal needle is used for lesions less than 8 cm in depth, and a Chiba needle is used for lesions situated deeper than 8 cm.

The number of passes obtained is usually at the discretion of the interventional radiologist performing the procedure. Additional passes are obtained in cases of suspected lymphoma to obtain material for immunophenotyping by flow cytometry and cell block. If cytology shows no evidence of malignant transformation, a portion of the aspirate is sent for culture and sensitivity profiling.

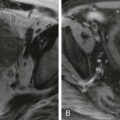

The complications that may be encountered include hemorrhage, pneumothorax, pleural effusion, and bowel injury ( Table 103-1 and Fig. 103-3 ). The most dreaded of the complications is uncontrolled non–self-limited hemorrhage, which may require blood transfusion, embolization, or splenectomy. One method to ensure hemostasis along the needle track is to inject gelatin sponge at the end of the procedure. However, if hemorrhage does occur nevertheless, it is then managed with aggressive fluid resuscitation and blood transfusions. Progressive hematomas not responding to conservative management may be subjected to catheter angiography with embolization. Splenectomy may be resorted to if all else fails.

| Study | Needle (gauge) | Patients | Complications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tam et al, 2008 | 22 | 147 | 1.9% major (two splenectomies) 14.7% minor |

| Liang et al, 2007 | 21, 18 | 46 | 2% |

| Kang et al, 2007 | 22 | 78 | None |

| Muraca et al, 2001 | 18-21 | 30 | None |

| Keogan et al, 1999 | 20-22 | 18 | None |

| Lieberman et al, 2003 | 20-22 | 20 | 10% minor (hemorrhage) |

| Lucey et al, 2002 | 18-23 | 24 | 10% (two splenectomies and one case of bleeding) |

In general, these complications occur with increasing frequency with increasing caliber of the biopsy needle. Fine-needle aspiration is generally considered safer than core biopsy. In one series, no complications were reported in 1000 blind fine-needle aspiration procedures done with 22-gauge needles, whereas another series reported a complication rate of 12% (four of 32 patients) with a 14-gauge core biopsy needle, with one patient needing splenectomy and three needing transfusions ( Table 103-1 ).

Catheter Drainage

Traditionally, splenic abscesses were managed with antibiotics, and splenectomy was resorted to if antibiotic treatment failed. Image-guided aspiration with catheter drainage is an excellent minimally invasive alternative with a high success rate. In addition to being less invasive than surgery, it also helps preserve the spleen and avoid the long-term immunologic dysfunctions seen with splenectomy.

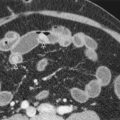

The ideal collection amenable to drainage is a unilocular collection with a discrete wall without internal septations or loculations. As with biopsy, collections in the periphery, especially in the middle or lower pole, are easier to drain. A trial aspiration is done, and the catheter is inserted if frank pus is aspirated. The most commonly used catheters are the pigtail catheters in varying sizes ranging from 7F to 12F ( Fig. 103-4 ). In general, more viscous abscesses need larger bore catheters, and the catheter may need to be upgraded to a larger one in case of inadequate drainage.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree