Clinical Considerations

Primary neoplasms of the small bowel are uncommon and, although about 40 different histologic types of benign and malignant tumors have been identified, they constitute only 1% to 5% of all gastrointestinal neoplasms. Almost 75% of the tumors found at autopsy are benign, whereas most of the symptomatic tumors and tumors detected at surgery are malignant. Regardless of the relative incidence of benign and malignant small bowel tumors, the low susceptibility of the small bowel to neoplastic transformation is remarkable when one considers its length, total mucosal surface area, and diversity of structural elements.

Benign small bowel tumors are usually discovered in patients between 50 and 80 years of age and occur with equal frequency in men and women. Symptomatic patients may present with abdominal pain and other clinical features of partial or intermittent small bowel obstruction. Intussuscepting neoplasms may cause significant intestinal obstruction and benign tumors are involved in most adult cases. Bleeding from benign tumors occurs in 40% to 50% of symptomatic patients. Anemia, occult bleeding, or intermittent gastrointestinal (GI) hemorrhage may be caused by ulceration of an epithelial adenoma or the mucosa overlying an intramural tumor. In clinical investigations in which enteroclysis was used to evaluate GI bleeding, small bowel neoplasms accounted for 50% of the diagnostic findings, with an almost equal detection of benign and malignant tumors. Constitutional symptoms such as malaise, anorexia, and weight loss are uncommon in patients with benign small bowel neoplasms, as is the ability to palpate the tumor on clinical examination.

Imaging Considerations

Diagnosis of benign small bowel neoplasms remains a dilemma because of the vagueness and paucity of symptoms as well as the difficulty in detecting these lesions on conventional radiologic studies. Because benign small bowel neoplasms are relatively uncommon, most radiologists do not have adequate experience with these tumors, so delayed or inaccurate diagnosis is common. More sophisticated diagnostic methods of intestinal evaluation in patients suspected of small bowel neoplastic disease have been advocated.

Barium-based methods of enteroclysis have been shown to be a reliable technique for the demonstration of small bowel tumors and the evaluation of occult GI bleeding and intestinal obstruction. Enteroclysis may also allow for accurate differentiation of detected benign small bowel tumors. Computed tomography (CT) has now become the most readily available and commonly used imaging modality for the evaluation of patients with nonspecific abdominal symptoms. CT has the advantage of demonstrating intraluminal, mural, and extraintestinal abnormalities simultaneously. Certain CT findings can differentiate benign and malignant small bowel tumors and, for some benign tumors such as lipomas and leiomyomas, may allow for a specific diagnosis. CT enteroclysis further improves the advantages inherent in multidetector CT (MDCT) scanners by using techniques of small bowel infusion via an enteric tube. Whether performed with positive enteral contrast media (e.g., iodinated, water-soluble) or preferably with neutral enteral contrast media (e.g., water) with intravenous (IV) contrast enhancement, CT enteroclysis has been shown to be an accurate method for the diagnosis of small bowel neoplasms, with a reported sensitivity and specificity of 85% and 97%, respectively. CT enterography, an enteric CT study without intubated intestinal infusion, is an alternative to CT enteroclysis for the investigation of small bowel neoplasms.

CT enterography is dependent on the patient’s ability to ingest a sufficient volume of oral contrast over a short period of time and interindividual variation in bowel transit time. The choice between the intubation-infusion method (enteroclysis) and oral approach (enterography) is one of preference and may also depend on the clinical indications, patient population, radiology practice, and diagnostic algorithms used by different centers. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the small bowel has been advocated because of its superior soft tissue contrast resolution, which allows for the differentiation of various pathologic changes in the bowel wall, multiplanar imaging capability, lack of associated exposure to ionizing radiation, possibility of repeated serial acquisitions, and elimination of the need for an iodinated contrast medium. Small bowel capsule endoscopy, although a sensitive technique for the detection of mucosal disease, including intestinal polyposis, has been shown to have limitations in the diagnosis of small bowel tumors.

Specific Tumors

Although numerous benign tumors can be found in the small bowel, approximately 90% are adenomas, GI stromal tumors, lipomas, or hemangiomas. Reports of benign tumors arising from almost all mesenchymal cell types have appeared sporadically in the literature. Benign small bowel tumors often display similar morphologic features on imaging studies. Although a specific histologic diagnosis may be difficult, useful diagnostic observations can be made based on the number and location of tumors and on certain radiologic features that differentiate these lesions.

Adenoma

Adenomas found within the small bowel are benign glandular epithelial neoplasms that are classified similarly to colonic adenomas and may exhibit a malignant predisposition. Approximately 40% are villous adenomas, and the remainder show a tubular or tubulovillous morphology. As with colonic adenomas, the finding of cellular atypia, a villous component, or large size increases the risk for malignancy. Most patients with adenomas are asymptomatic, but they may occasionally present with GI bleeding or intestinal obstruction secondary to intussusception.

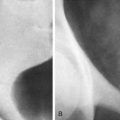

Most adenomas are small (1-2 cm) and have smooth or slightly lobulated contours. They may appear on barium studies as sessile or pedunculated intraluminal polyps or as small mural nodules on enteroclysis ( Fig. 44-1 ). Radiologic differentiation from other polypoid lesions, such as polypoid carcinoma, hamartomatous or inflammatory polyp, or other small submucosal neoplasms, is difficult.

Although small bowel adenomas usually occur as solitary lesions, multiple lesions may be found as a manifestation of hereditary multiple polyposis syndromes (e.g., familial adenomatous polyposis syndrome, Gardner’s syndrome). Villous adenomas are sessile and lobulated, usually larger than most adenomatous polyps, have a strong predilection for the duodenum, and carry a higher risk for malignant transformation ( Fig. 44-2 ).

Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) constitute a major subset of GI mesenchymal neoplasms and are characterized immunohistologically by the expression of c-kit protein (CD117). These are typically single, firm, circumscribed neoplasms, usually found in the stomach and small bowel. GI bleeding, obstruction from intraluminal growth and compression or intussusception are common clinical manifestations.

In reported preoperative series of patients with small bowel tumors, features on barium enteroclysis allowed for the accurate preoperative diagnosis of GISTs in 83% to 100% of patients. Submucosal tumors appear as smooth, round, or semilunar mural defects that are demarcated by sharp angles with the intestinal wall ( Fig. 44-3 ).

CT is particularly useful in depicting the nature and extent of small bowel GISTs. These tumors appear on CT as sharply defined masses that display a homogeneous soft tissue density and uniform contrast enhancement. It is difficult to predict the malignant potential of these tumors by imaging alone; however, experience with CT suggests that malignant GISTs are larger than benign tumors, less uniform in shape, and of heterogeneous tissue attenuation. A more detailed discussion of GISTs can be found in Chapter 45 .

Lipoma

Lipomas of the small bowel account for 20% to 25% of all GI lipomas, and the small bowel represents the second most common site for the occurrence of GI lipomas. These benign neoplasms arise as a well-circumscribed submucosal proliferation of fat that usually grows intraluminally; outward extension tends to be impeded by the firmness of the muscularis propria. Small bowel lipomas are usually solitary, relatively avascular lesions of variable size (1-6 cm). Most of these tumors occur in the ileum. Although most patients with lipomas are asymptomatic, some may present with intermittent intestinal obstruction, possibly secondary to intussusception ( Fig. 44-4 ).

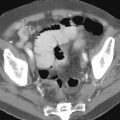

Barium studies demonstrate a sharply demarcated, often pedunculated tumor that tends to conform to the contour of the small bowel lumen. The configuration of the tumor may change during fluoroscopy with compression or peristalsis of the small bowel. CT can be diagnostic of small bowel lipoma by showing that the lesion has attenuation values consistent with those of fat ( Fig. 44-5 ). The presence of soft tissue stranding within an otherwise uniform lipoma on CT has been attributed to fibrovascular changes associated with ulceration of the tumor.

Hemangioma

Benign angiomatous tumors are hamartomatous vascular growths, which are most likely congenital. Two principal forms are described—papillary (capillary) hemangiomas and cavernous hemangiomas. Cavernous hemangiomas predominate in the small bowel, occurring as simple polypoid tumors or, rarely, as diffusely expansile lesions. Microscopically, these submucosal neoplasms consist of enlarged vascular channels or sinuses lined by endothelium and surrounded by minimal stromal tissue. Hemangiomas may be single or multiple. Although most hemangiomas are only millimeters in size, some may enlarge and protrude into the lumen. Direct invasion of the mucosa or penetration beyond the serosa is uncommon.

In contrast to other small bowel tumors, which are less likely to cause symptoms, 80% of patients with hemangiomas are symptomatic. Most of these patients present with GI bleeding that is often acute, severe, and intermittent. Anemia and occult fecal blood loss are also common clinical findings.

Hemangiomas must be of sufficient size to produce an intraluminal or intramural nodular defect on barium studies ( Fig. 44-6 ). Although a rare occurrence, the finding of calcified phleboliths on abdominal radiographs can suggest the diagnosis. When discovered in patients with vascular cutaneous lesions or tuberous sclerosis, Turner’s syndrome, or Osler-Weber-Rendu disease, such radiographic findings should increase suspicion for intestinal hemangiomas. Mesenteric arteriography may be performed to demonstrate an intestinal vascular abnormality, but differentiation between small vascular tumors and other vascular malformations is difficult. In one reported case, CT demonstrated a large jejunal hemangioma that appeared as a heterogeneous mass with prominent mesenteric vasculature. CT enteroclysis and CT enterography performed with neutral enteral and IV contrast media have the potential to demonstrate a vascular hemangioma, provided that the tumor is of sufficient size and the intestinal lumen is distended enough for optimal mural visualization ( Fig. 44-7 ).