Atherosclerotic disease of the major intracranial arteries is a frequent cause of stroke. In addition, many patients who have symptomatic intracranial stenosis are at very high risk for recurrent stroke. Preliminary studies suggest that angioplasty and stenting may reduce the risk of stroke in patients who have severe stenosis of intracranial arteries. Data for angioplasty and stenting, however, consist of case series; no randomized studies have been completed to date. This article reviews these data and discusses the rationale for a randomized trial of angioplasty and stenting versus best medical management for patients who have symptomatic intracranial stenosis.

Atherosclerotic stenosis affecting the major intracranial arterial is a common cause of stroke in North America, particularly in some minority populations . Patients presenting with transient ischemic attack (TIA) or stroke and severe (>70% diameter reduction) stenosis are at a very high risk for future stroke . The mechanism of stroke in these patients may be related to thromboembolism resulting from biologic plaque factors, hemodynamic factors resulting from flow reduction beyond the stenosis, or synergistic effects of the two . Angioplasty and stenting offer the potential to address both mechanisms and to reduce stroke risk substantially. Angioplasty and stent technology has improved dramatically during recent years. There are accumulating data on the technical success and safety of these procedures, but the long-term reduction of the risk of stroke remains undetermined. At present, only one device, the Wingspan self-expanding stent (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA), is approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in patients who have symptomatic atherosclerotic stenosis (50%–99%) of intracranial arteries.

This article discusses the outcome of medically treated patients who have intracranial stenosis, drawing heavily from the recently reported Warfarin versus Aspirin for Symptomatic Intracranial Disease (WASID) study . It then reviews the published data for intracranial angioplasty, with and without stenting. Finally, it discusses the rationale for a randomized trial of angioplasty and stenting for symptomatic intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis.

Epidemiology

Atherosclerotic stenosis of large intracranial arteries accounts for approximately 10% of ischemic strokes that occur in North America. There is racial and ethnic variance in this disease. Intracranial arterial stenosis is responsible for 6% to 10% of ischemic strokes in whites, 6% to 29% of ischemic strokes in blacks, 11% of ischemic strokes in Hispanics, and 22% to 26% of ischemic strokes in Asians . These figures project to approximately 70,000 strokes per year in the United States , compared with the 140,000 strokes caused by extracranial carotid stenosis and 70,000 strokes caused by nonvalvular atrial fibrillation .

Pathophysiology

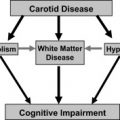

The mechanisms of ischemic stroke related to intracranial atherosclerotic disease include thromboembolic factors, such as in situ thrombosis and distal embolism and hemodynamic factors resulting from flow reduction and lack of adequate sources of collateral flow . As discussed in the article by Derdeyn in this issue, both mechanisms are commonly involved in most patients and probably are synergistic. Lee and colleagues , reviewed diffusion-weighted MR imaging in 63 acute patients who had ischemic stroke and who had stroke who had ipsilateral middle cerebral artery (MCA) disease, 32 of whom showed multiple lesions. Most patients had perforating artery infarcts, either solitary or accompanied by pial or border-zone territory infarcts. These data suggest that local branch occlusion and simultaneous distal embolization is a common stroke mechanism in patients who have MCA disease. The present authors measured hemodynamics in 10 patients who had symptomatic MCA occlusion or stenosis, using positron-emission tomography . Blood flow and oxygen extraction were normal in four of the five patients who had stenosis. These data suggest that most patients who have symptomatic intracranial stenosis are symptomatic as the result of thromboembolic factors.

Nevertheless, hemodynamic impairment is a risk factor for stroke in patients who have intracranial occlusive disease, just it is as in those who have extracranial carotid artery occlusive disease. Amin-Hanjani and colleagues measured quantitative bulk flow in the basilar artery and its branches in 50 patients who had symptomatic vertebrobasilar disease. Forty-seven of the 50 patients were followed for a mean of 28 months, although those who had low flow were offered intervention. None of the 31 patients who had normal distal flow had a recurrent event. Several of the 16 patients who had low flow suffered recurrent strokes before intervention.

Pathophysiology

The mechanisms of ischemic stroke related to intracranial atherosclerotic disease include thromboembolic factors, such as in situ thrombosis and distal embolism and hemodynamic factors resulting from flow reduction and lack of adequate sources of collateral flow . As discussed in the article by Derdeyn in this issue, both mechanisms are commonly involved in most patients and probably are synergistic. Lee and colleagues , reviewed diffusion-weighted MR imaging in 63 acute patients who had ischemic stroke and who had stroke who had ipsilateral middle cerebral artery (MCA) disease, 32 of whom showed multiple lesions. Most patients had perforating artery infarcts, either solitary or accompanied by pial or border-zone territory infarcts. These data suggest that local branch occlusion and simultaneous distal embolization is a common stroke mechanism in patients who have MCA disease. The present authors measured hemodynamics in 10 patients who had symptomatic MCA occlusion or stenosis, using positron-emission tomography . Blood flow and oxygen extraction were normal in four of the five patients who had stenosis. These data suggest that most patients who have symptomatic intracranial stenosis are symptomatic as the result of thromboembolic factors.

Nevertheless, hemodynamic impairment is a risk factor for stroke in patients who have intracranial occlusive disease, just it is as in those who have extracranial carotid artery occlusive disease. Amin-Hanjani and colleagues measured quantitative bulk flow in the basilar artery and its branches in 50 patients who had symptomatic vertebrobasilar disease. Forty-seven of the 50 patients were followed for a mean of 28 months, although those who had low flow were offered intervention. None of the 31 patients who had normal distal flow had a recurrent event. Several of the 16 patients who had low flow suffered recurrent strokes before intervention.

Outcome of medically treated patients

The WASID trial generated the best estimates of the outcome of medically treated patients who have symptomatic intracranial atherosclerotic disease . This section reviews the data from this study in detail, including secondary analyses identifying particularly high-risk patients. It also reviews the current data for risk factor management in this population. These data are important, because angioplasty and stenting should target the patients at the highest risk for stroke with medical therapy. Most of these patients have vascular risk factors that should be treated as well.

Warfarin versus Aspirin for Symptomatic Intracranial Disease trial

The WASID trial was a randomized, double-blinded, multicenter, controlled study designed to determine the relative efficacy of aspirin (1300 mg/d by mouth) versus anticoagulation with warfarin (target international normalized ratio [INR], 2.0–3.0) in patients who had angiographically proven 50% to 99% stenosis of a major intracranial artery and a recent TIA or minor stroke .

At total of 569 patients were enrolled between 1999 and 2003. The median time from qualifying event to randomization was 17 days. Mean follow-up was 1.8 years. Baseline clinical characteristics between the two groups were similar. These baseline characteristics also were very similar to those in prior clinical trials in patients who had atherosclerotic extracranial carotid stenosis or occlusion . The majority of patients had a history of hypertension or smoking. A large minority had diabetes or a prior coronary artery disease. Subjects could be screened by transcranial Doppler, magnetic resonance angiography, or CT angiography. Enrollment required confirmation of 50% to 99% stenosis with catheter angiography . The study drug was discontinued by more warfarin patients than aspirin patients (28.4% versus 16.4%, P < .001). The mean INR was 2.5. The percentage of maintenance time was 23% at a target INR of 2.0 or lower, 63% at a target INR of 2.1 to 3.0, 13% at a target INR of 3.1 to 4.0, and 1% at a target INR higher than 4.0.

The primary end point was any ischemic stroke, brain hemorrhage, or death from nonstroke vascular cause. The primary end point was reached in 22.1% of the aspirin group and 21.8% of the warfarin group. The probability of ischemic stroke in the territory of the stenotic artery at 1 year was 12% in the aspirin group and 11% in the warfarin group. At 2 years, the probabilities of ipsilateral ischemic stroke were 15% and 13%, respectively. Warfarin was associated with a higher rate of nonvascular death (1.1% versus 3.8%, P = .05) and major hemorrhage (3.2% versus 8.3%, P = .02). Data were nearly identical when analyzed by on-treatment analysis. The study was halted at the recommendation of the Data Safety and Monitoring Board because of excess mortality in the warfarin arm. The conclusion of the WASID trial was that aspirin should be preferred over warfarin for the treatment of symptomatic intracranial disease because of the lack of evidence for benefit with warfarin and lower risks of death and major bleeding with aspirin.

Subgroup analyses in the Warfarin versus Aspirin for Symptomatic Intracranial Disease trial

Prior retrospective studies had reported that certain subgroups of patients who have intracranial arterial stenosis are at particularly high risk of stroke. These subgroups include patients who had severe stenosis or vertebrobasilar disease or who did not respond to antithrombotic therapy . The WASID trial provided a unique opportunity to determine prospectively whether these and other risk factors are associated with an increased risk of stroke in the territory of a stenotic intracranial artery. In a pooled analysis of all 569 patients in the WASID trial, ischemic stroke in any vascular territory occurred in 106 patients (19.0%); 77 (73%) of the strokes were in the territory of the stenotic artery . In univariate analyses, severity of stenosis (≥70% versus <70%), time from qualifying event to enrollment (≤17 days versus >17 days), female gender, score on the National Institutes of Health (NIH) stroke scale (>1 versus ≤1), and a history of diabetes mellitus were significantly associated ( P ≤ .05) with stroke in the territory of the stenotic artery; body mass index was of borderline significance ( P = .068). Age, race, location of stenosis (ie, vertebrobasilar disease versus carotid-MCA disease), length of stenosis, other vascular risk factors, comorbidities, and treatment with antithrombotic agents at the time of the qualifying event (so-called “medical failures”) were not significantly associated with an increased risk of stroke in the territory of the stenotic artery. Multivariate analysis showed that the only significant predictors of stroke in the territory were severity of stenosis (≥70% versus <70%), time from qualifying event to enrollment (≤17 days versus >17 days), score on the NIH stroke scale (>1 versus ≤1), and female gender.

Severity of stenosis was the most powerful predictor of stroke in the territory and increased linearly (p-value for trend =.0026) with greater percent stenosis. The rates of stroke in the territory of the stenotic artery in patients who had a TIA or stroke and 70% or greater stenosis were 18% at 1 year (95% confidence interval [CI], 13%–24%) and 19% at 2 years (95% CI, 14%–25%), whereas the rates of stroke in the territory of the stenotic artery in patients who had a TIA or stroke and less than 70% stenosis were 6% at 1 year (95% CI, 4%–10%) and 10% at 2 years (95% CI, 7%–14%). Notably, two of the variables that previously had been associated with increased risk of stroke in retrospective studies, vertebrobasilar disease and lack of response to antithrombotic therapy, had no association with an increased risk for ipsilateral stroke. The current indication for the Wingspan device, which is approved by the FDA under a Humanitarian Device Exemption (HDE) for the treatment of intracranial stenosis, is for patients who have 50% to 99% stenosis and who have cerebral ischemic events during antithrombotic therapy. The data from the WASID trial do not support this requirement of failed antithrombotic therapy before using the Wingspan device.

Another important finding in the WASID trial was that 60 of the 77 strokes in the territory of the stenotic artery (78%) occurred within 1 year of enrollment. The magnitude of stroke risk and the temporal pattern of risk are nearly identical to data reported for the medical treatment arms of clinical trials for symptomatic extracranial carotid stenosis and occlusion . Whether the decrease in stroke risk after 1 year reflects improvement in hemodynamic factors, embolic factors, or both over time is unclear.

A second subgroup analysis compared the outcomes with warfarin and aspirin in different subgroups of patients . These subgroups were classified by time from qualifying event, age, gender, race, smoking, hypertension, diabetes, coronary artery disease, site of symptomatic lesion (middle cerebral, anterior cerebral, internal carotid, vertebral, and basilar arteries), anterior versus posterior circulation, per cent stenosis, length of stenosis, and antithrombotic therapy at the time of qualifying event. No definite differences in the risk of stroke or vascular death with aspirin or warfarin were observed in any of these subgroups, but the power of the study to detect differences in these subgroups was low.

In summary, angioplasty and stenting cannot be justified in patients who have stenosis of less than 70%, given the low risk of stroke in the territory of a stenotic artery (6% at 1 year) and the inherent risk of angioplasty and stenting (30-day rate of stroke and death in the range of 4%–7%, as discussed in the next section). Furthermore, lack of response to medical treatment should not be used as an indication for angioplasty and stenting. Patients in whom this procedure should be considered are those who have severe stenosis, recent ischemic symptoms, and a score on the NIH stroke scale greater than 1.

Medical management

Risk factor management in the WASID trial was performed by the study neurologist and primary care physicians, according to published national guidelines on hypertension , hyperlipidemia , and diabetes (American Diabetes Association) . Despite these recommendations, many vascular risk factors were poorly controlled. Poorly controlled blood pressure and elevated low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels were the most important risk factors for stroke, vascular death, or myocardial infarction during follow-up in WASID. During a mean of 1.8 years of follow-up, 30.7% of patients who had a mean systolic blood pressure of 140 mm Hg or higher had a stroke, vascular death, or myocardial infarction, compared with 18.3% of patients who had a mean systolic blood pressure lower than 140 mm Hg ( P < .0005). Over the same period, 25.0% of patients who had LDL levels of 115 mg/dL (the median LDL) or higher had a stroke, vascular death, or myocardial infarction, compared with 18.6% of patients who had a mean LDL level below 115 mg/dL ( P = .03). Considering an LDL target level of less than 70 mg/dL, 22.5% of patients who had a mean LDL above this target had a stroke, myocardial infarction, or vascular death, compared with 7.4% of those who had a mean LDL below this target (odds ratio 3.13; 95% CI, 0.77–12.67). Poorly controlled blood pressure and an elevated LDL level also were important risk factors for ischemic stroke alone in the WASID trial. The risk of any ischemic stroke was found to increase with increasing mean systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure ( P < .0001 and < 0.0001, respectively) using a log-rank trend test. Elevated systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure also were associated with increased risk of ischemic stroke in the territory of the stenotic artery ( P = .0065 and < 0.0001, respectively) . An LDL of 115 mg/dL (the median value) or higher was highly correlated with ischemic stroke (odds ratio 1.82; 95% CI, 1.17–2.83; P = .0072) .

These risk factor data suggest that optimal outcome for patients who have intracranial atherosclerotic disease, including those who undergo angioplasty and stenting, requires careful and intensive adjunctive risk factor management. Further support for the importance of risk factor management in patients who have intracranial stenosis is provided by recent secondary prevention stroke trials that have shown treatment of elevated LDL and blood pressure reduces the risk of recurrent stroke. Additionally, intensive risk factor management in patients who have coronary artery disease has been shown to reduce major cardiac events and stroke and to be as effective as endovascular intervention and usual or aggressive medical management for preventing cardiac ischemic events in patients who have stable angina and severe atherosclerotic coronary artery disease .

There are few data regarding the optimal antiplatelet regimen in this population. The WASID trial tested high-dose aspirin (1300 mg/d) and found it to be equivalent to warfarin in reducting the risk of stroke. There are no data on the effectiveness or safety of other antiplatelet agents specifically in patients who have intracranial stenosis. In other stroke populations with heterogeneous causes of stroke, the combination of aspirin and clopidogrel therapy was found to be equivalent to monotherapy in reducing the risk of stroke , and the combination of low-dose aspirin and dipyridamole has been shown to be more effective than low-dose aspirin for stroke prevention .

Angioplasty/stenting as a treatment for symptomatic intracranial stenosis

During the past decade, angioplasty and stenting have emerged as therapeutic options for symptomatic intracranial arterial stenosis. The first report of angioplasty for intracranial atherosclerotic disease was in 1980 . Since then there have been dramatic improvements in balloon and stent technology and in the imaging systems that provide the guidance for these procedures.

Angioplasty alone

There have been no prospective studies of intracranial angioplasty without stent placement. Technical success (defined as reduction of stenosis to < 50%) can be achieved in more than 80% of patients, and the rate of stroke or death within 30 days of angioplasty has varied between 4% and 40% in several retrospective angioplasty studies . One reason for the wide variation in complication rates may be variability in the acuity of patients being treated. Procedures that were largely elective were associated with lower complication rates (4%–6%) . Restenosis rates following angioplasty alone range from 24% to 40% . There are limited data on the long-term outcome after intracranial angioplasty alone. Marks and colleagues reported an annual stroke rate of 4.4% (3.2% in the territory of stenosis) in a recent retrospective review of 120 patients who underwent intracranial angioplasty at four sites. The actual stroke rate is uncertain, given the retrospective nature of the study and the lack of adjudication of events by neurologists. Although some practitioners strongly advocate the use of this procedure alone (ie, without a stent), most favor the use of stents. This preference can be attributed to several technical drawbacks to angioplasty, including immediate elastic recoil of the artery, dissection, acute vessel closure, residual stenosis of greater than 50% following the procedure, and high restenosis rates. These limitations, coupled with the success of stenting in the coronary circulation, have led to stenting becoming the preferred interventional technique for treating intracranial stenosis.

Stenting

Until recently, most data on the safety and efficacy of intracranial stenting have been limited to single-center series . The largest of these studies are summarized in Table 1 . These data suggest that intracranial stenting can be performed relatively safely and with high technical success. The larger, more recent studies suggest that the rate of stroke after stenting in patients who have 70% to 99% stenosis may be substantially lower than the rate of stroke in the patients who had equivalent stenosis in the WASID trial. Data exist for three categories of stents: bare-metal balloon expandable, drug-eluting balloon expandable, and self-expanding stents.