Normal Anatomy, Normal Ultrasound

The normal anatomy of the anus can be evaluated through ultrasound with great accuracy. The structures include the anal mucosa, the internal anal sphincter (IAS), the external anal sphincter (EAS), the puborectalis, the perineal body, the seminal vesicles in a man, and any bowel that may fall into a particularly deep cul-de-sac at the level of the upper anal canal.

The anal canal is divided into three general levels, each of which demonstrates different characteristics: upper, mid, and lower. The upper anal canal is marked by the visualization of the puborectalis muscle, which appears as a U-shaped sling surrounding the anus at the superior-most border of the sphincters. Here, the seminal vesicles and occasionally some bowel may also be seen anterior to the anus (Figure 12-1).

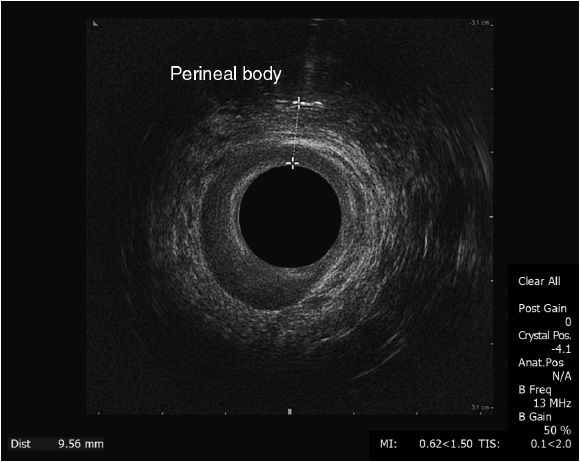

The mid-anal canal is best identified by a clear delineation of the IAS and the EAS in the shape of dark and white rings, as well as an inner layer of mucosa containing the hemorrhoidal bundles (Figure 12-2). Any disruption of these rings can be an indication of the abnormalities that would be the source of the patient’s complaint. A measurement of the perineal body can be done at this time of the examination by placing a finger against the posterior wall of the vagina to highlight that structure and measuring the distance between that and the anterior mucosa of the anus. Normal thickness of the perineal body is generally considered to be anything greater than 8 or 9 cm.

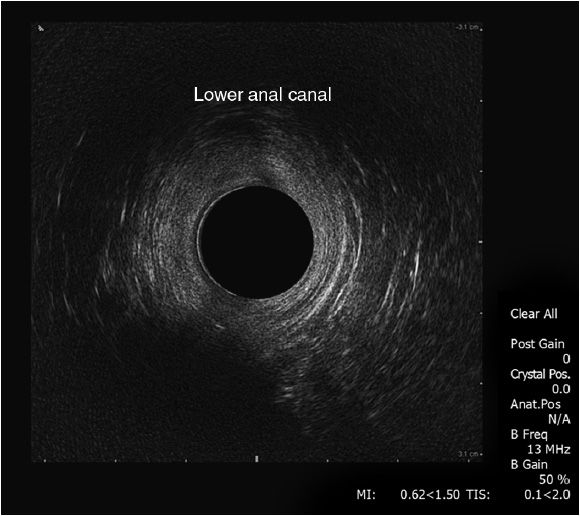

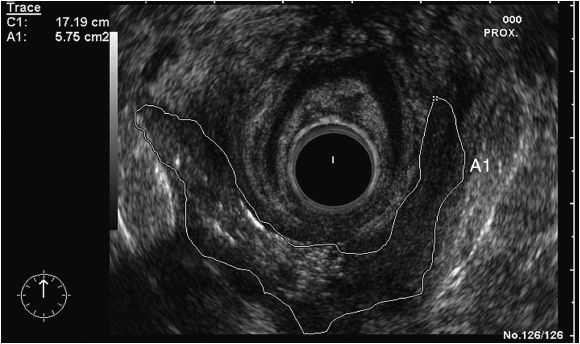

The distal anal canal is discernible by the loss of the internal anal sphincters, leaving the EAS alone as a distinct structure (Figure 12-3). In the surrounding soft tissues beyond the anal canal and rectum lie the various perianal and perirectal spaces that become significant in the setting of malignancy and infection, but are not usually of much moment in a normal patient.

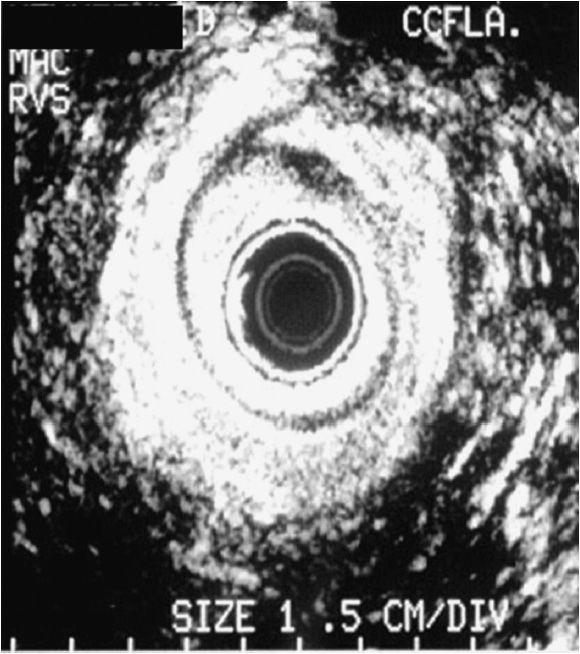

Normal rectal anatomy is also represented by light and dark rings, but the rings now correlate to the different layers of muscle and mucosa (Figure 12-4).1 The perirectal fat is generally a heterogeneous shade of gray, in which enlarged lymph nodes can be identified by dark, circumscribed spots within the fat. These can sometimes be confused with perirectal vessels, but the vessels can be distinguished by moving the probe and following their linear courses, rather than limited area circumscribed by the outlines of a node.

Figure 12-4. Rectal ultrasound. First white line: interface of balloon and mucosa; first dark line: mucosa, muscularis mucosae; second white line: submucosa; second dark line: muscularis propria; third white line: interface of rectum and perirectal fat.

Scanning Technique for Obtaining These Images

Scanning Technique for Obtaining These Images

The patient is brought into the office procedure room or endoscopy suite and placed in the left lateral decubitus position. Sedation is not generally necessary, although it is an option for an anxious patient or if a patient has a bulky tumor around which manipulation of an ultrasound probe might be too uncomfortable. The ultrasound unit is set up and the patient’s information is entered.

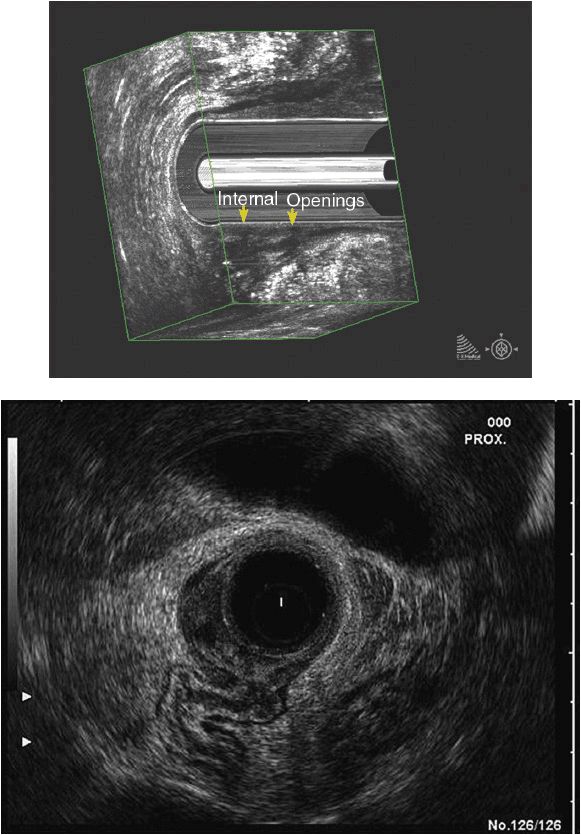

For an anal ultrasound, a 10-MHz transducer is generally used for close-up images; this is attached to the end of the ultrasound probe. A small rigid cap is fitted over the transducer and filled with saline. After doing a visual examination of the external anal canal and an initial digital examination, the probe is lubricated and placed into the anal canal. The operator will know when the upper anal canal is reached by identifying the puborectalis sling. Orientation is also achieved by turning the probe until the sling is shown to resemble the letter “U” with the lateral arms reaching upward. The probe is then withdrawn slowly to the mid- and then distal-anal canal, looking for abnormalities. The perineal body in a woman is measured in the manner previously described at the mid-anal canal (Figure 12-5). The 3-D function available on some scanners has the advantage of not needing to withdraw the probe and the ability to manipulate the image in any direction.

Rectal ultrasounds are performed in a slightly different manner. The patient is prepared with an enema prior to the procedure. The 10-MHz transducer is preferred for examination of shallower structures, while the 7-MHz transducer is chosen for deeper, more distant structures. Again, for most purposes, the 10-MHz transducer is generally sufficient. A latex balloon is attached to the probe and inflated with saline, taking care to remove all air bubbles. It is then desufflated prior to insertion. The external anus is visualized and a digital examination performed. A rigid proctoscope is passed transanally and the target lesion examined, taking care to mark distance, size, quadrant, and characteristics. The proctoscope is advanced to a level just proximal to the lesion in order to ensure that the entire lesion can be examined by the ultrasound. The probe is passed through the proctoscope; once the transducer is past the open end of the scope, the scope can be withdrawn slightly for better manipulation. The balloon is then inflated so that the rectal wall is fully distended for optimal contact with the rectal mucosa. The probe is again withdrawn slowly, marking the disruption of the light and dark lines, and looking for any prominent lymph nodes in the surrounding perirectal fat. As with the anal ultrasound, a 3-D module is available to help in creating a block of images that can be examined in an infinite variety of ways after the examination.

Common Findings/Abnormalities

Common Findings/Abnormalities

Possibly the most common reason for performing an anal ultrasound is in the workup of fecal incontinence. In conjunction with pudendal nerve latency testing, anal manometry, and defecography, anal ultrasound can confirm structural defects and scarring in the internal and external anal sphincters.2 The likeliest origin of anal incontinence is sphincter damage after vaginal delivery, often presenting decades after the inciting injury.3 Sphincter defects should be suspected in a peri- or postmenopausal woman with a history of vaginal delivery, many times complicated by high-birth-weight babies, prolonged labor, use of vacuum or forceps assistance, or episiotomy. Common findings in these patients include anterior scarring or a complete break of the IAS and/or the EAS (Figure 12-6),4 and thinning of the perineal body (less than 8 mm thickness on digital examination at the mid-anal canal).5 Some amount of anterior scarring, which appears as a break in the rings of tissue with mixed echogenicity, is likely present in many women in the general population; it is unclear what distinguishes those women who are symptomatic from those who are not.6 However, confirmation of scarring can help delineate surgical options for these patients. Specifically, an overlapping sphincteroplasty is an option for the appropriate patient. In cases of recurrence of symptoms after such an operation, or for follow-up evaluation after this procedure, an ultrasound may be performed. This shows a classic “6” or “reverse 6” sign in an intact repair (Figure 12-7).7

Other patients who have fecal incontinence and have no history of traumatic vaginal delivery may have other findings. Multiple or eccentric tears, or scarring, or no scarring at all can be evident from less common types of injuries, limiting the options for surgical intervention. Congenital anomalies can be delineated by ultrasonography and help to determine what structures are absent or aberrant. It can also be useful in identifying occult rectovaginal fistulas, which may mimic or add to the symptoms of fecal incontinence.

Another common use of ultrasound is the evaluation of an anal abscess or anal fistula.8 Abscess cavities and any fistulous tracts can be seen on ultrasound as dark cavities outlined in white (Figure 12-8).9 This mode of evaluation is especially useful in tracing complex or high fistula tracts that would be difficult to follow by other methods. The injection of hydrogen peroxide into the external opening of a fistula will make the tract hyperechoic from the bubbling effect of the fluid from oxygenation and help to distinguish it from other structures in the surrounding tissue.10

Anal tumors, both benign and malignant, can be clearly examined with anal ultrasound. Sonographic images can show the relationship of benign tumors to anal anatomy and define tissue planes. Most lesions will be hypoechoic, and ultrasound-guided biopsies may be performed by an advanced operator. Malignant tumors, most commonly squamous cell carcinomas, can be used in pre-and post-treatment staging. While some of the rarer cancers may warrant surgical intervention, the treatment of squamous cell malignancies of the anus is largely radiation. Incomplete response or recurrence can be followed by serial ultrasounds. Staging follows a standard TNM protocol (Tables 12-1 and 12-2) and can be measured either by diameter or by depth of invasion.11 Staging by ultrasound is labeled by a “u” preceding the standard nomenclature to distinguish it from the final pathologic designation.