CHAPTER 60 Aortic and Mitral Valvular Disease

AORTIC STENOSIS

Definition

Aortic stenosis is obstruction to left ventricular outflow at or near the level of the aortic valve. The stenosis can be subvalvular, supravalvular, or valvular. The valvular stenosis is by far the most frequently encountered type in adults, most commonly secondary to calcification of tricuspid or congenitally bicuspid aortic leaflets.1

Prevalence

Aortic stenosis has become the most common valvular disease in the Western world, largely because of the increased life expectancy of the population. The prevalence of aortic stenosis in the population older than 65 years is 2% to 7%; aortic sclerosis, the precursor to aortic stenosis in which there is valve thickening but no stenosis, is present in approximately 25% of this age group.2,3 Whereas aortic stenosis is seen in patients with both tricuspid and bicuspid aortic valves, the patients with bicuspid aortic valves will become symptomatic and present for valve replacement an average of one to two decades earlier in life.4 Nonatherosclerotic causes of aortic stenosis, such as rheumatic and congenital, are rare in the developed world.2

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Aortic stenosis should be considered part of a disease continuum in which initially non–hemodynamically significant valve thickening and calcification eventually progress to heavily calcified, immobile leaflets causing obstruction of left ventricular outflow. The early, asymptomatic portion of this continuum may last several decades; the symptomatic phase is often short and rapidly progressive, with a 2-year survival rate of 50% after onset of symptoms.4 At that point, only aortic valve replacement can reverse the poor prognosis and offer long-term survival.

Aortic stenosis is associated with several risk factors, the main ones being increased age, male gender, hypertension, smoking, diabetes mellitus, and elevated serum low-density lipoprotein and elevated lipoprotein levels.1,4 Aortic stenosis is an active disease process that follows a pattern similar to that seen in vascular atherosclerosis—inflammation followed by lipid accumulation and dystrophic calcification.3 The aortic calcifications tend to accumulate preferentially at the edges of the valve leaflets, which influences valvular function.

Manifestations of Disease

Clinical Presentation

Aortic stenosis in asymptomatic patients is usually identified incidentally during the cardiac auscultation portion of the physical examination, when note is made of a late systolic murmur or a normally split second heart sound. Symptomatic patients can present with angina, syncope, dyspnea on exertion, and eventually symptoms of heart failure.1 The patient’s symptoms are associated with the degree of stenosis at the level of the aortic valve and with the degree of resulting left ventricular dysfunction. As the stenosis becomes more significant, with a higher pressure gradient across the valve, the left ventricle responds to the systolic pressure overload with concentric hypertrophy. Whereas this increased wall thickness is the expected, appropriate adaptation to increased pressure, it in turn causes a diastolic dysfunction that reduces cardiac output. In addition, hypertrophy may also cause reduced or imbalanced distribution of coronary blood flow, thereby increasing the risk of subendocardial ischemia and worsening the symptoms of heart failure.1

Imaging Indications

The grading of aortic stenosis is based on several values—the valvular orifice area, the pressure gradient across the valve, and the stenotic jet velocity—all of which require imaging for measurement. Transthoracic echocardiography is the imaging modality of choice and therefore the gold standard for grading of aortic stenosis severity. The severity of symptoms does not always correlate with the degree of stenosis, and some patients with moderate stenosis become symptomatic, whereas others with severe stenosis by imaging criteria remain without symptoms.1 The importance of this is underlined by the fact that the timing of therapy depends more on the presence of symptoms than on the grade of aortic stenosis.2

Imaging Techniques

Radiography

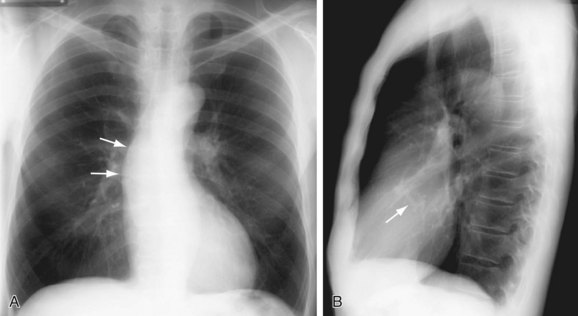

The most prominent finding on chest radiographs in adults with aortic stenosis is enlargement of the ascending aorta, although extent of dilation does not directly correlate with severity of stenosis (Fig. 60-1).5 Conversely, the degree of aortic valve calcification does correlate with disease severity. Other, less specific findings, such as pulmonary venous congestion and pulmonary edema, can occur late in the disease process as a result of left ventricular dysfunction.5

Echocardiography

As previously noted, echocardiography is the gold standard for evaluation of aortic stenosis. It is the modality of choice for both initial diagnosis and assessment of disease severity as well as for re-evaluation and monitoring of both asymptomatic patients and those in whom symptoms have appeared or are progressing.1 In general, asymptomatic patients with mild to moderate stenosis are monitored every 1 to 2 years; those with moderate to severe stenosis are evaluated every 6 to 12 months.4

In addition to evaluating the valve orifice size and velocity of the stenotic jet, echocardiography can be used to assess the thickness of the left ventricular wall as well as left ventricular size and function. By use of the modified Bernoulli equation (ΔP = 4V2), the pressure gradient across the valve is calculated by measuring the peak velocity of the flow jet. Whereas a normal aortic valve has a peak jet velocity of 0.9 to 1.8 m/sec, a peak pressure gradient of less than 25 mm Hg, and a valve orifice area of 2.0 to 3.5 cm2, a severely stenotic valve will have a peak velocity of more than 4.0 m/sec, a peak gradient of more than 64 mm Hg, and a valve area of less than 0.5 cm2.4

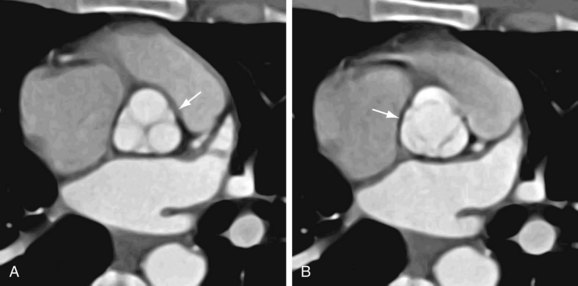

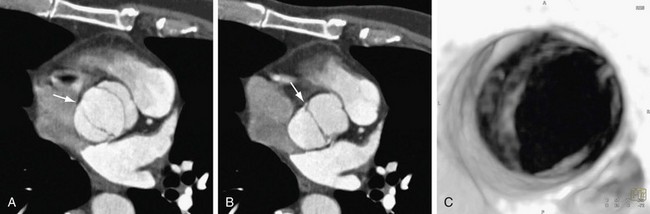

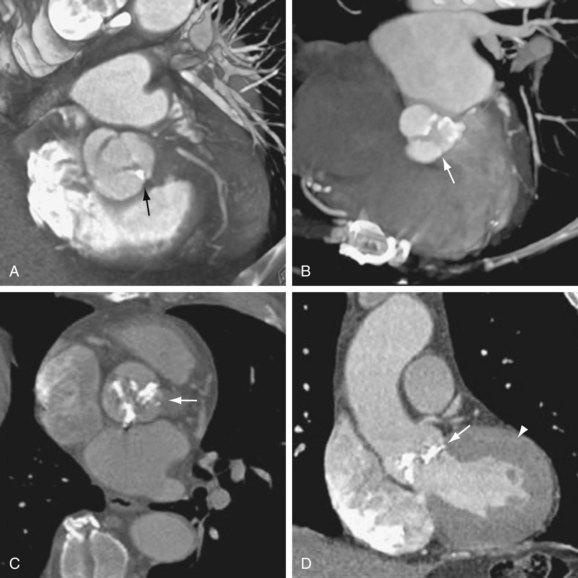

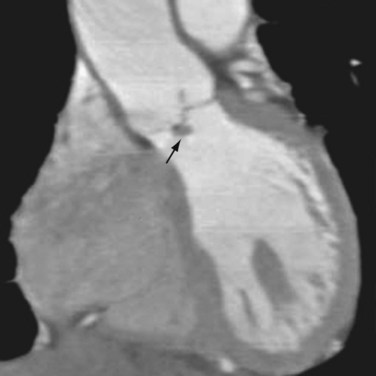

Computed Tomography

Although echocardiography will likely continue to be the first-line modality for diagnosis, grading, and monitoring of aortic stenosis, ECG-gated multislice CT can add more information in patients in whom clinical symptoms for some reason do not match the echocardiographic findings or in patients who are technically challenging.6 The main advantage of CT over transthoracic echocardiography, other than being faster, is the more reliably accurate measurement of valve orifice area by planimetry, which in CT is not limited by hemodynamic factors, such as low cardiac output, as it is in transthoracic echocardiography (Figs. 60-2 and 60-3).6 In addition, CT can give a reproducible assessment and quantification of valve calcification, a major component of stenosis that correlates with its severity (Figs. 60-4 and 60-5).7 Newer multidetector CT scanners do not require pretreatment with β blockers for rate control if the heart rate is below 85 beats/min and allow a dynamic display of valve motion throughout the full cardiac cycle.8 The main disadvantages of CT, in addition to the relatively higher cost and lower availability, are radiation and the need for intravenous administration of contrast material.

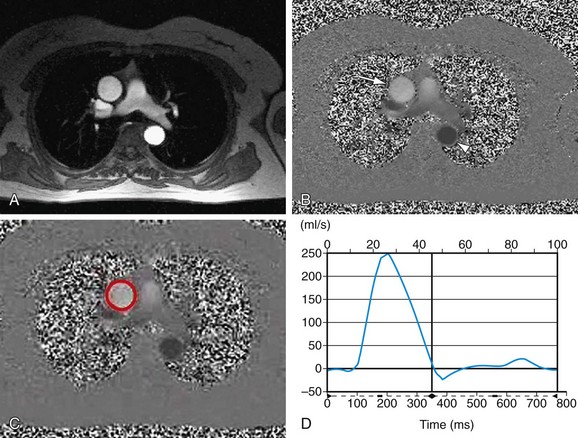

Magnetic Resonance

Qualitative assessment of aortic valve stenosis can be performed by steady-state free precession (SSFP) cine MR because of the excellent temporal resolution, which allows highly accurate evaluation of valve motion.7 A signal void due to spin dephasing representing the stenotic jet is identified projecting from the valve toward the proximal aorta. Adequate quantitative measurements are not possible with the SSFP MR technique. For quantification of aortic stenosis, phase contrast MR imaging is typically used. With this technique, the peak flow of the jet in the ascending aorta can be measured, and as with echocardiography, the pressure gradient can be calculated by the modified Bernoulli equation (ΔP = 4V2) (Fig. 60-6). A disadvantage of MR in evaluation of aortic stenosis is the poor visualization of leaflet calcification, a major factor in the disease process.

Treatment Options

Medical

The key elements of medical management of asymptomatic patients with aortic stenosis include advising against strenuous exercise in cases of moderate to severe stenosis; antibiotic prophylaxis against endocarditis for dental or other interventional procedures; antihypertensive therapy; and close monitoring both of the severity of stenosis and for appearance of symptoms.1 The last item is of great importance, both because disease progression tends to be unpredictable and as surgical therapy, namely, aortic valve replacement, is usually indicated once symptoms appear or are thought to be imminent. Recognition of the onset of symptoms can be especially difficult in patients with other comorbidities, and special attention needs to be paid to any change in tolerance of strenuous activity or appearance of chest pain in either rest or stress.1

Surgical

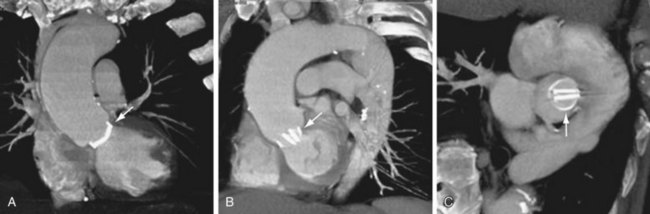

As the combined risk of aortic valve replacement (up to 10% mortality in the elderly or in those with severe comorbidities) and complications associated with having a prosthetic valve (2% to 3% per year) is much greater than the risk of sudden cardiac death in the asymptomatic patient, even those with severe stenosis by imaging, surgical therapy is usually not indicated until symptoms appear.4 The exception to this rule of thumb is if there is significant stenosis-related left ventricular dysfunction or if there has been a substantial increase in peak aortic jet velocity (>0.3 m/sec within 1 year), indicating imminent onset of symptoms.2

In terms of surgical techniques, open aortic valve replacement is the conventional surgical therapy, with either a bioprosthesis or a mechanical valve (Fig. 60-7). The mechanical valves have a longer lifespan, but they require permanent anticoagulation and are therefore usually used in younger patients. Aortic balloon valvotomy can sometimes be used to relieve stenosis, although it is usually reserved for young patients without valve calcifications. In older adults, it is used only in cases of palliation in poor surgical candidates or as a temporary bridge to valve replacement in clinically unstable patients.4

FIGURE 60-1

FIGURE 60-1

FIGURE 60-2

FIGURE 60-2

FIGURE 60-3

FIGURE 60-3

FIGURE 60-4

FIGURE 60-4

FIGURE 60-5

FIGURE 60-5

FIGURE 60-6

FIGURE 60-6

FIGURE 60-7

FIGURE 60-7