Imaging Methods

Ultrasound (US) remains the primary imaging modality to evaluate an adnexal mass. When faced with a known or suspected adnexal mass, there are numerous possibilities to be considered. In the majority of cases, US findings should allow either one diagnosis to be considered most likely or significantly narrow the likely possibilities to a few entities. In the uncommon instance where the likely diagnosis is not clear by US, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is generally the next best imaging modality. MRI is most useful when the mass has an unusual sonographic appearance (such that it is not typical of malignancy or of any of the common benign entities), is of unclear origin, or when the mass is not well visualized by US (which is most commonly the result of body habitus and/or the superior or lateral location of the mass).

Computed tomography (CT) is useful for staging masses suspected of being ovarian cancer but has little role in the routine characterization of adnexal masses. Although adnexal masses are usually evident by CT and are often detected incidentally by CT, the CT features of most adnexal masses do not usually allow a confident diagnosis. Admittedly, if CT identifies fat in an ovarian mass, a dermoid can be diagnosed. CT may be able to identify features of malignant masses, but when considering all adnexal masses, US and MRI have better predictive value than CT and also do not use ionizing radiation. CT may be helpful, however, in some patients with tuboovarian abscess, for whom CT may allow better depiction of the extent of inflammatory change. Positron emission tomography (PET) or PET/CT scans also have little to no role in the routine characterization of an adnexal mass.

Ovarian Versus Extraovarian Masses

It is important to remember that not all adnexal masses arise in the ovary. Extraovarian masses account for 2% to 10% of adnexal masses in surgical series. The majority of extraovarian adnexal masses are benign and most commonly are due to hydrosalpinges, paraovarian cysts, and peritoneal inclusion cysts. When one considers that such masses, particularly small paraovarian cysts, are not removed surgically in many patients, the frequency of extraovarian masses among all ovarian masses may be higher than 2% to 10%.

Although most adnexal masses arise from the ovary, diagnostic errors will be made if one does not consider the possibility that an adnexal mass may arise outside the ovary. Gynecologic adnexal masses may arise from the fallopian tubes or supporting ligaments of the uterus. The most likely diagnoses are different, depending on the origin of the mass. Thus, when one encounters an adnexal mass, an attempt should be made to determine whether the mass arises from the ovary or is extraovarian in origin. There will be cases where it is not clear whether the mass arises from the ovary. This is more likely to occur with a large mass, a superiorly located mass, or in a postmenopausal patient in whom the normal ovary may be small and difficult to identify. Occasionally a typical sonographic appearance (e.g., hydrosalpinx or dermoid, as discussed in this and other chapters) may allow a confident diagnosis even if the origin of the mass is not clear. In general, however, determination of an ovarian versus extraovarian origin will allow one to be more specific in making a diagnosis based on imaging features.

An ovarian origin is most easily recognized by observing ovarian parenchyma around the periphery of at least part of the mass. This tends to be easier in premenopausal women, in whom ovarian follicles facilitate identification of the ovary. Tiny echogenic foci have also been described as an occasional normal finding in ovaries and, if present, may assist in identification of ovarian parenchyma.

Extraovarian masses are sometimes obvious when a separate ipsilateral ovary is evident. If there is an adnexal mass and the ipsilateral ovary is not seen, transvaginal scanning with gentle pressure using the transducer and/or with palpation on the patient’s lower abdominal wall with the examiner’s other hand may displace bowel and allow identification of a normal ovary. We have also found that trying to follow the broad ligament as one sweeps laterally from the edge of the uterus will sometimes allow identification of the ovary. Ovaries that are located more superiorly or laterally in the pelvis may escape detection by transvaginal scanning yet be evident by transabdominal scanning.

Sometimes the adnexal mass is at the edge of the ovary, and it is unclear whether the mass arises from the ovary or is just located immediately adjacent to the ovary. Applying gentle pressure with the transvaginal transducer and/or with the examiner’s other hand on the patient’s lower abdomen may allow one to separate the mass from the ovary and confirm an extraovarian origin. Particularly for solid masses when a pedunculated uterine leiomyoma is a consideration, color or power Doppler US may be useful to demonstrate a vascular connection to the uterus (see Chapter 15 ). Pedunculated uterine leiomyomas may infrequently undergo cystic degeneration and present an even more challenging issue in distinction from ovarian neoplasms. Ovarian fibromas can occasionally be pedunculated from the ovary and hence be challenging to diagnose, but this is an infrequent occurrence. MRI is often useful when there is a solid adnexal mass and one cannot determine by US whether the mass arises from the ovary or is extraovarian in origin. The most common differential diagnosis in this situation is a pedunculated uterine leiomyoma versus an ovarian fibroma. The distinction is important because a pedunculated leiomyoma would likely not be treated in an asymptomatic patient, whereas an ovarian fibroma (or other solid ovarian mass) would usually be treated surgically.

Most extraovarian masses that one will encounter will be of gynecologic origin. Occasionally, masses may be of gastrointestinal (GI) tract or neural origin. Extraovarian masses will be discussed in the next section. Tubal pregnancy typically appears as an extraovarian adnexal mass and is discussed in Chapter 22 . Ovarian masses are discussed in Chapter 29 , Chapter 30 .

Extraovarian Masses

Extraovarian masses are most often found when evaluating a patient for adnexal fullness, mass, or pain. Because the majority of the etiologies of extraovarian masses are benign, many are also incidentally discovered. Evaluating the pelvis for adnexal masses becomes difficult when a definite ovary is not identified or the relationship to the ovary is difficult to determine. There are many extraovarian masses that simulate ovarian pathology, whether cystic, solid, or mixed cystic and solid. Discriminating the possible etiologies may be difficult in any given imaging modality. US can be useful in identifying the follicles of the ovary and origin of vascular flow; however, CT is often better at imaging GI tract causes of pelvic paraovarian masses, and MRI may sometimes be superior in evaluating the fallopian tubes and uterus, as well as evaluating for blood products. Extraovarian masses may be gynecologic in origin, such as hydrosalpinx or pedunculated fibroids. Multiple nongynecologic etiologies, however, also exist for extraovarian pelvic masses.

Gynecologic

Tubal or Broad Ligament

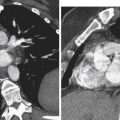

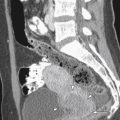

Tubal etiologies account for a large portion of paraovarian adnexal masses. The most common is hydrosalpinx. Hydrosalpinx may occur secondary to tumor blocking the distal fallopian tube, endometriosis, pelvic inflammatory disease, ectopic pregnancy, iatrogenic ligation, or adhesions. Because hydrosalpinx is often mistaken for a cystic ovarian mass, there are several sonographic features to look for during evaluation. The most common finding is a long tube-shaped fluid-filled structure, but this is not specific. If this finding is combined with the “waist sign,” which is described as two opposing indentations, or with an incomplete septation (really just the wall of the tube folded back on itself), the specificity and sensitivity increase. The wall may be echogenic and contain linear or polypoid excrescences caused by thickened endosalpingeal folds. The fluid within the tube may be anechoic or have the appearance of debris with or without layering. Discriminating hydrosalpinx from pyosalpinx or hematosalpinx is not well done with imaging and is better correlated with clinical symptomatology and clinical history. The appearance of complex fluid sonographically (i.e., with internal echoes), however, would favor hematosalpinx or pyosalpinx ( Figure 28-1 ). MRI is helpful in further evaluation, demonstrating a separate ovary and the signal characteristics of the fluid, for example, the higher T1 signal of blood products. MRI is also able to better demonstrate the C- or S-shape appearance of the dilated tube and the cause of the obstruction (see Figure 28-1 ).

If the pyosalpinx also encompasses the ovary, this is called a tuboovarian abscess (see Chapter 10 , Chapter 17 ), and a normal ovary is not identified. The appearance is that of a complex mass with varying amounts of fluid, septations, and solid tissue. With history and clinical findings suggestive of active inflammation, this may be diagnosed with US or CT.

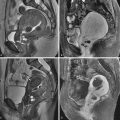

Paraovarian or paratubal cysts are another type of cystic paraovarian mass that account for up to 20% of all adnexal masses. These are benign round or oval fluid collections adjacent to the fallopian tube or ovary that arise from the broad ligament. Paraovarian cysts may be remnants of a Wolffian duct (mesonephric), müllerian duct (paramesonephric), or mesothelial elements. As asymptomatic masses, these are usually incidentally found on cross-sectional imaging, although torsed paraovarian cysts have been identified and may present with pain. Imaging usually demonstrates single unilocular anechoic thin-walled simple cysts that are separate from the ipsilateral ovary ( Figure 28-2 ); however, multiloculated and bilateral cysts have also been identified. If papillary projections are present within the paraovarian cyst, then cystadenofibroma, cystadenoma, and serous papillary borderline tumors should be considered. Malignant lesions such as endometrioid cystadenocarcinoma, serous cystadenocarcinoma, and mucinous cystadenocarcinoma are rare in a paraovarian cyst.

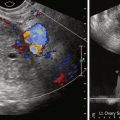

Fallopian tube carcinoma is rare, with an incidence of 3.7 per million compared with 120 per million for ovarian cancer. Fallopian tube carcinomas are serous carcinomas 90% of the time. These neoplasms may be found during evaluation for pelvic mass or ascites. Peak incidence is in the fifth decade. Imaging can be helpful if a separate ovary is identified. Histologically this tumor is indistinguishable from serous carcinoma of the ovary and is determined by invasion of the fallopian tube without involvement of the ovary. These are discussed in more detail in Chapter 34 . The appearance varies, but a tubular-shaped cystic mass with a significant solid component is suggestive ( Figure 28-3 ).