A radiologist friend from another city called one day and asked for a review of his wife’s mammogram. She had been recalled from screening, told that the findings were probably benign, and asked to return in 6 months for a follow-up mammogram. He thought that there might be some architectural distortion present and wanted a second opinion. After review and a few additional images, architectural distortion was indeed identified. Biopsy showed invasive lobular carcinoma. She was stage I. They send a case of champagne every year on the anniversary of her diagnosis. Joie de vivre!

Architectural distortion (AD) is often a subtle sign of malignancy with a high positive predictive value of approximately 60% on diagnostic mammography. Detection of AD is challenging because it is often similar in density to the surrounding parenchyma and it may contain fat. It is often changeable in appearance in different projections or visible on only a single view. For these reasons, AD is a common cause of false-negative screening mammograms and is also frequently missed by computer-aided detection (CAD).

How to Recognize Architectural Distortion

AD can appear as radiating lines, alteration of the normal tissue contours, or both. It is described in the BI-RADS Atlas as follows:

The normal architecture is distorted with no definite mass visible. This includes thin lines or spiculations radiating from a point and focal retraction or distortion of the edge of the parenchyma. AD can also be associated with a mass, asymmetry, or calcifications.

AD can be the primary finding or an associated finding (e.g., a mass or calcifications with associated AD).

Radiating Lines

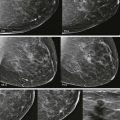

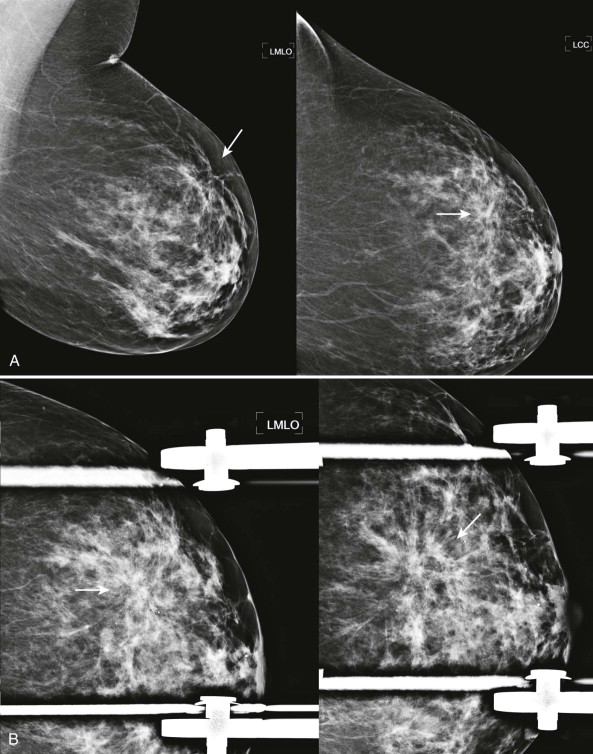

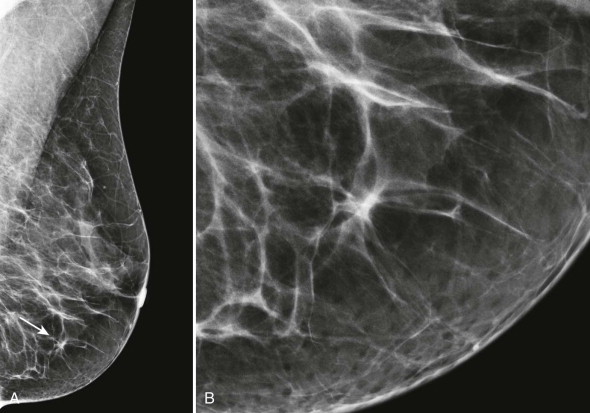

The classic appearance of AD is radiating lines without a visible central mass ( Fig. 9-1 ). If a central mass is visible, the finding is more accurately described as a mass with spiculated margins rather than AD. Imagine you are looking at the flight map in an airline magazine: looking for AD is like looking for hub cities. Normal overlapping structures (fibrous bands, ducts, and blood vessels) create patterns resembling intersecting flight paths.

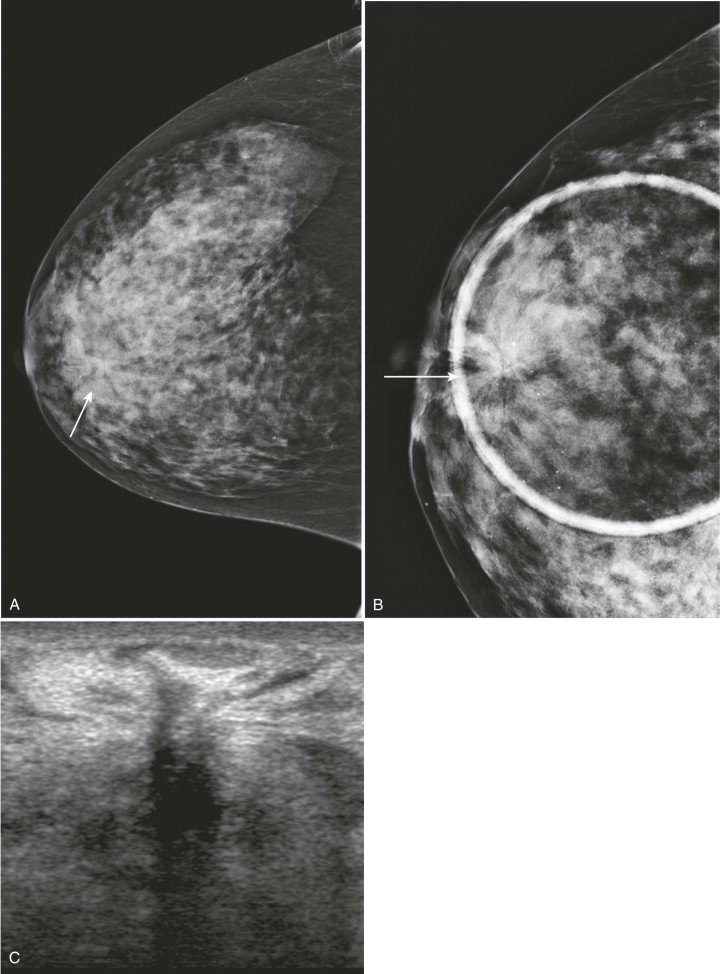

The lines of AD may not radiate in all directions or be symmetric about a central point. Only a portion of the distorted area may be visible. Think of these as a coastal hub such as LaGuardia airport in New York City. Most of the incoming flights arrive from the West, with many fewer arriving from the East ( Fig. 9-2 ). Detection of even a few lines that appear to radiate from a central point or are associated with tissue retraction warrants careful examination and often diagnostic evaluation.

Abnormal Tissue Contours

Another presentation of AD results from tethering or retraction of tissue, causing abnormal tissue contours (see Fig. 9-1 ). These findings can appear mammographically as straightening of the Cooper ligaments, focal retraction, or angulation of tissue contours. It is as though a crochet hook had been dragged through the tissue at that spot.

Distorted tissue contours are often detected at the interface between the parenchymal tissue and the subcutaneous or retroglandular fat (see Fig. 9-1 ). During mammographic interpretation, it is important to evaluate these borders and to compare the tissue contours with previous studies.

Differentiating Architectural Distortion from Summation Artifact

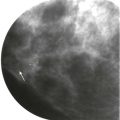

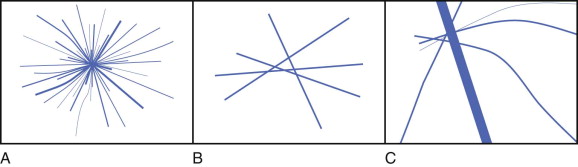

Overlapping Cooper ligaments, ducts, and vessels may mimic the pattern of AD. However, these overlapping structures never actually radiate from a central point. What may appear at first glance to be AD on screening mammography may often be dismissed after close inspection without the need for additional imaging.

Normal lines extend through and beyond the center of the questioned finding, rather than ending at the central point, as occurs with true AD ( Fig. 9-3 ). If we use our airline route map analogy, normal structures represent overlapping flight paths rather than the hub city.

One technique that can be used to analyze questioned AD is to deconstruct the finding by visually subtracting the definitely normal structures, then imagining what it would look like without those structures. If the resulting appearance would no longer be suspicious, it is consistent with summation artifact ( Fig. 9-4 ). If you believe normal structures cannot fully account for the suspected distortion, additional evaluation is needed.

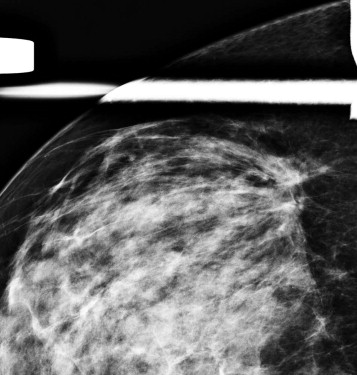

Diagnostic Evaluation of Suspected Architectural Distortion

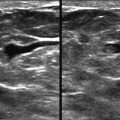

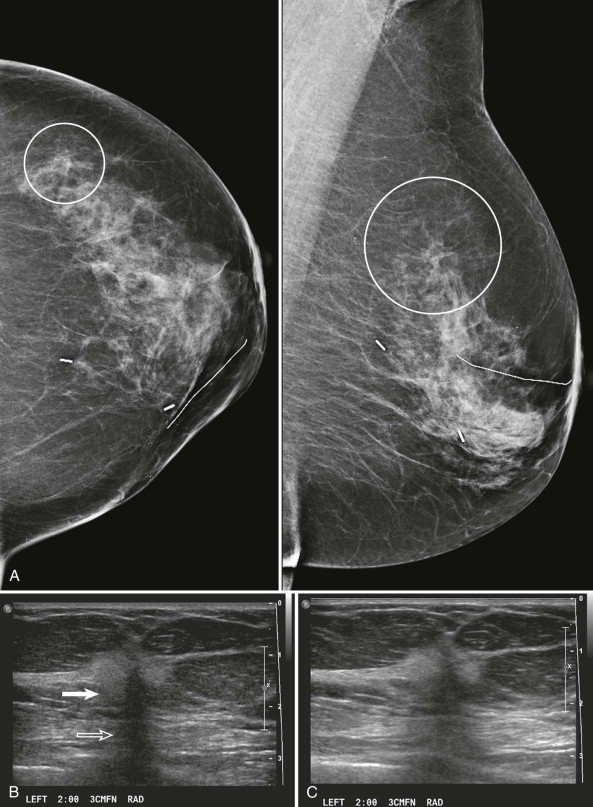

When AD is suspected on screening mammography, it should be evaluated in greater detail on diagnostic views ( Fig. 9-5 ). True AD will usually persist and appear more pronounced on spot compression views. Associated masses, asymmetries, or calcifications may also become apparent on these views.

Ultrasonography (US) is often useful in confirming, characterizing, and localizing lesions presenting as AD (see Fig. 9-5 ) and in detecting associated masses that may be mammographically occult. Harmonic tissue imaging improves conspicuity of some lesions presenting as AD. However, the use of compound imaging can eliminate the posterior acoustic shadowing often seen with AD—particularly when due to invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC)—and may make these lesions more difficult to detect ( Fig. 9-6 ). The lack of a US correlate should not eliminate the consideration of biopsy if distortion is present on the mammogram.

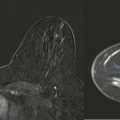

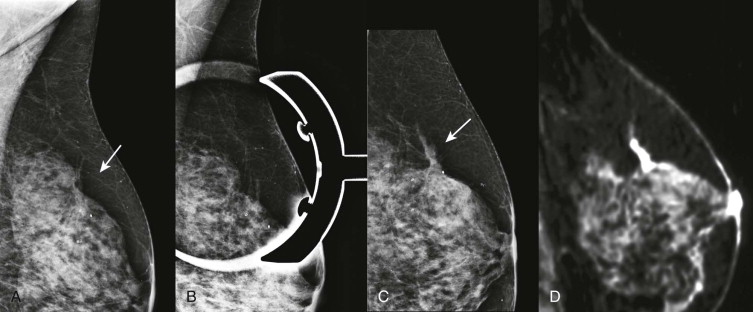

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be useful in a problem-solving role for occasional cases of questioned AD that are not resolved by diagnostic mammography or US ( Fig. 9-7 ). Keep in mind that even MRI does not have sufficiently high negative predictive value to avoid biopsy of AD that is mammographically suspicious.

Differential Diagnosis of Architectural Distortion

Malignancies presenting as AD usually represent either infiltrating ductal or infiltrating lobular carcinoma. Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) uncommonly presents with this appearance ( Box 9-1 ).

- •

Infiltrating ductal carcinoma

- •

Infiltrating lobular carcinoma

- •

Radial scar/complex sclerosing lesion

- •

Postsurgical change

- •

Fat necrosis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree