Clinical Presentation

The patient is an 82-year-old man who has noted progressive walking difficulty and weakness in the legs over the last 6 months. Patient had an L3-L5 lumbar decompression 2 years earlier for spinal stenosis and noticed only partial improvement in his symptoms. Patient feels he is weak from the hips inferiorly. He can stand for only 5 minutes and walk for just 200 yards before his legs become weak. He has collapsed several times when he was unable to sit down. The patient now walks with the aid of a cane in his right hand and has developed a scoliosis. Patient denies radicular pain. Patient has occasional incontinence. Electromyogram (EMG) demonstrates severe chronic multilevel lumbar radiculopathies on the left with diffuse sensory and motor peripheral neuropathy.

Imaging Presentation

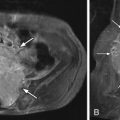

Sagittal and axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance (MR) images demonstrate a long segment region of abnormal increased signal intensity involving much of the central spinal cord from the mid thoracic region to the conus medullaris. There are multiple small ovoid regions of intermediate signal intensity along the dorsal aspect of the spinal cord. The findings represent arteriolized venous structures secondary to an extradural arteriovenous fistula with spinal cord ischemia that is likely secondary to venous hypertension and the high flow of shunted arterial blood from the fistula leading to deprivation of blood or “steal” from the spinal cord ( Fig. 11-1 ) .

Discussion

Spinal arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) and arteriovenous fistulas (AVFs) are a group of various disorders. By definition, an AVM is an abnormal communication between the arterial and venous systems. This connection may be a simple fistula or a more complex communication. It is important to recognize the signs and symptoms of a spinal AVM because it can, in its early stages, resemble various causes of low back pain and weakness. Many patients have undergone surgical procedures for symptoms presumably related to spinal stenosis and/or foraminal narrowing only to discover later that the problem was a spinal AVM.

Traditionally, spinal AVMs have been classified as types I to IV, but more recently, Spetzler and colleagues have offered a new classification system based on specific anatomic and pathophysiologic factors. These factors include whether the AVM is extradural or intradural, ventral or dorsal, or intramedullary in location and whether there are single or multiple feeding branches.

Initial symptoms related to venous congestion include paresthesias and/or radicular pain. Low back pain is frequently seen. There may be weakness and gait abnormalities. Symptoms are progressive and often ascending. Later in the disease process, bowel and bladder incontinence, erectile dysfunction, and urinary retention can be seen.

Type I (Intradural Dorsal AVF)

Intradural dorsal arteriovenous fistulas (AVFs) are the most common type of spinal AVF, representing 60% to 80% of spinal AVMs. They are most common in males (5:1) and are more commonly found in the thoracic region. Patients with AVFs usually present in the fifth to seventh decade of life. Type I fistulas are composed of a single radicular feeding artery (type I-A) or multiple radicular feeding arteries (type I-B) that communicate(s) with the venous system of the spinal cord at the dural sleeve of the nerve root. Whether there are single or multiple radicular feeding arteries, there remains only a single intradural fistula. This then leads to compromise of spinal cord venous outflow with arteriolization of the coronal venous plexus, venous hypertension, and progressive myelopathy.

Type II (Intramedullary AVM)

Intramedullary arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) have a nidus (Latin for “nest”) similar to intracranial AVMs. They have been referred to as classic AVMs or glomus-type lesions. Intramedullary AVMs are the second most common type of spinal AVM, representing 19% to 45% of cases. Type II lesions are found equally in men and women and manifest in the third or fourth decade of life. These AVMs are associated with aneurysms in up to 44% of cases and typically manifest with hemorrhage, either parenchymal or subarachnoid, or compression-induced acute myelopathy. Intramedullary AVMs are further subdivided into compact or diffuse depending on the vascular architecture of the nidus. These lesions can have single or multiple feeding arteries from branches of the anterior spinal artery (ASA) and posterior spinal artery (PSA). They are characterized by high pressure, relatively low resistance, and high blood flow.

Type III (Extradural-Intradural AVM)

Type III lesions, extradural-intradural arteriovenous malformations, are also known as juvenile or metameric AVMs. These lesions respect no tissue boundary and can involve bone, muscle, skin, spinal canal, spinal cord, and nerve roots. These lesions are invested along a particular somite level. When the lesion involves the entire somite level, it has been called Cobb’s syndrome . Type III AVMs are extremely rare and have a poor prognosis. They usually manifest early in life with bruits and myelopathy.

Type IV (Intradural Ventral AVF)

Type IV, or perimedullary-type arteriovenous malformations (AVMs), are located in the ventral midline subarachnoid space. These lesions arise directly from the ASA and are true fistulas without an intervening capillary network. Blood flow is rapid through these fistulas and can produce flow-related aneurysms and venous hypertension. Over time, the size and flow of the fistula increase, and the signs and symptoms related to progressive vascular steal and spinal cord compression become more pronounced. These patients can present with progressive venous hypertension myelopathy or hemorrhage. These fistulas have been subdivided into three subtypes based on the size and flow through them. Type IV-A lesions are small and have a single feeder. Blood flow is slow through Type IV-A lesions and venous hypertension is moderate. Type IV-B lesions are intermediate with a major feeder from the ASA and minor feeders at the level of the fistula. Type IV-C lesions are giant fistulas with large shunt volumes and large tortuous draining veins. The high flow through Type IV-C lesions leads to vascular steal from the spinal cord arterial supply and spinal cord ischemia.

Extradural Arteriovenous Fistulae

Extradural arteriovenous fistulae arise from a direct connection between an extradural artery, usually arising from a branch of a radicular artery, and an extradural vein of the epidural venous plexus. This leads to engorgement of the epidural venous system, compression of the spinal cord and nerve roots, and progressive myelopathy. High venous pressure in the epidural venous system can lead to intradural venous hypertension. The high flow of shunted arterial blood from these fistula can also lead to steal from the spinal cord and ischemia.

Conus Medullaris AVM

The conus medullaris AVM consists of multiple feeding arteries, multiple niduses, and a complex venous drainage. There are multiple arteriovenous shunts that arise from the ASA and PSA with glomus-type niduses. These AVMs are always located in the conus medullaris and cauda equina but can also extend along the entire filum terminale. Clinically, they can manifest with venous hypertension, ischemia, compression, or hemorrhage, but unlike other spinal AVMs, they frequently produce symptoms of radiculopathy and myelopathy at the same time.

Imaging Features

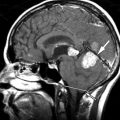

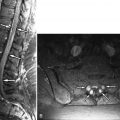

Myelography demonstrates multiple curvilinear filling defects in the contrast column along the surface of the negative defect of the spinal cord. Computerized tomography (CT) may demonstrate an enlarged spinal cord and also enhance vessels along the surface of the spinal cord ( Fig. 11-2 ) . Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging has a distinct advantage in that it will demonstrate whether or not there are signal changes intrinsic to the spinal cord compatible with edema and/or ischemia. When the spinal cord is affected, T1-weighted MR images demonstrate an enlarged hypointense spinal cord. The spinal cord may demonstrate increased T2 signal centrally as well as flow voids along the cord surface ( Fig. 11-3 ) . Heterogeneous signal can occasionally be seen if there is associated hemorrhage. T1-weighted post-contrast imaging will show multiple enhancing vessels ( Fig. 11-4 ) .