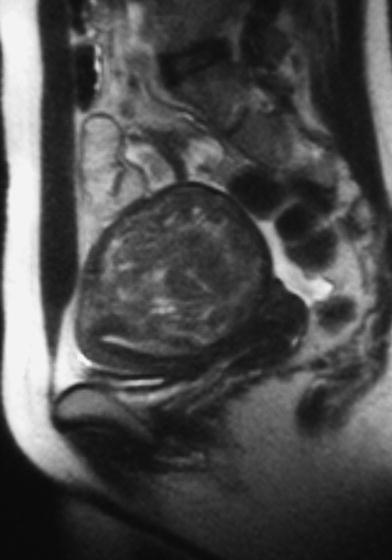

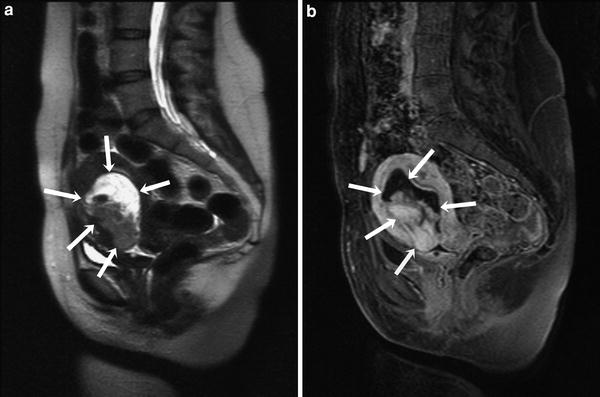

Fig. 1

MRI imaging for pre-procedure evaluation. Sagittal T2-weighted MR image of the pelvis demonstrating adenomyosis (arrows) in a patient previously diagnosed as having fibroids based on an ultrasound examination

The decision to routinely use MRI or to use it in selected cases in which ultrasound is not sufficient is based as much on resource availability as on medical necessity. It appears that MRI has some advantages over ultrasound in the pre-procedure evaluation of patients, but that advantage is not so great that MRI must be used. If ultrasound is to be the primary imaging tool, the study should be of high quality and the images made available for review. If there is uncertainty about the location or extent of fibroids, the degree to which they are in the uterine cavity or whether adenomyosis is an important part of the presenting condition, then MRI may be a valuable adjunct and should be considered.

2 Indications

Once a diagnosis has been confirmed, the first question is whether the fibroids detected in a patient require treatment. Many likely do not. The majority of women with fibroids do not have any fibroid-related symptoms and therefore conservative management, is the most appropriate approach (Parker 2007). Perhaps 20–30 % of women with fibroids will eventually develop symptoms that require therapy, but most transition into menopause without the need for therapy. In general, UAE is indicated for patients of reproductive age with symptomatic fibroids who wish to avoid surgery or for whom surgery is contraindicated.

2.1 Heavy Menstrual Bleeding

Heavy menstrual bleeding is the most common symptom among women seeking treatment for fibroids. Fibroids usually present with menorrhagia without interperiod bleeding, though submucosal fibroids can present with both menorrhagia and metrorrhagia. Symptomatic fibroids commonly increase the length of the menstrual cycles, the number of days with heavy bleeding, as well as the frequency of change of sanitary protection on the heaviest days. Typically, heavy menstrual bleeding is caused by fibroids that are either submucosal or intramural (Fig. 2). Serosal fibroids do not cause alterations to menstrual bleeding (Wegienka et al. 2003).

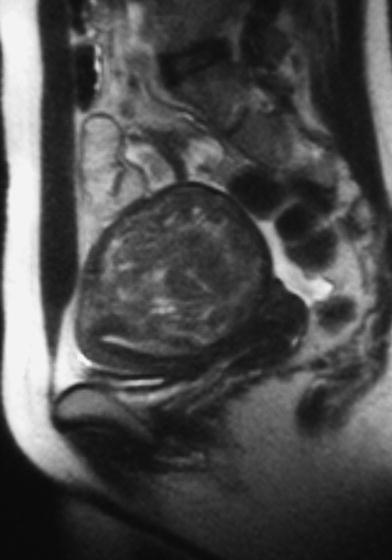

Fig. 2

Typical fibroid location in a patient with heavy menstrual bleeding. Sagittal T2-weighted MR image of the pelvis in a patient with a transmural posterior wall fibroid with substantial compression of the endometrial cavity. Because of the distortion of the endometrial cavity, the fibroid is likely the cause

The evaluation of the patient with menorrhagia varies depending on individual patient factors, but there are many causes for heavy menstrual bleeding beyond fibroids and these need to be considered carefully at the time of initial patient presentation. As indicated in the section above, a structured approach to the medical history (Munro et al. 2011), as well as collaboration with a gynecologist, is the best way to complete an appropriate evaluation that will help ensure the best patient outcomes.

2.2 Pelvic Pain and Pressure

Pelvic pressure, bloating, and pelvic pain are common with uterine fibroids and often most prominent before and during the perimenstrual period. Pelvic pain due to symptomatic fibroids is often described as discomfort more than pain, and usually is low grade and aching. Dysmenorrhea may develop or worsen in the presence of fibroids. Severe pain is atypical, but can occur with spontaneous fibroid degeneration. This is quite uncommon and other causes of female pelvic pain, such as endometriosis, should be considered. Variations of pelvic pain, such as dyspareunia, may also be caused by fibroids. When assessing a woman with pelvic pain and fibroids, it is important to correlate the location of the fibroids with the location of the pain. A patient with pain on the left with right-sided fibroids may have a different cause for the pain and further evaluation may be needed.

2.3 Urinary Symptoms

Urinary symptoms can also be caused by fibroids, particularly if the symptoms are urgency, frequency, or retention. Incontinence is unlikely to be solely caused by fibroids, but may be worsened by bladder compression from the enlarged fibroid uterus. Hydronephrosis from the enlarged uterus occurs in about 10 % of patients presenting for uterine embolization and is more likely in patients with significantly enlarged uteri from fibroids (Alyeshmerni et al. 2011). The hydronephrosis resolves as the uterus shrinks after uterine artery embolization in nearly all cases (Alyeshmerni et al. 2011; Mirsadraee et al. 2008).

2.4 Asymptomatic Fibroids

There are relatively few circumstances in which asymptomatic fibroids should be treated with UAE. Perhaps the most common is in a woman who has fibroids without symptoms who wishes to become pregnant. The link between fibroids and infertility and subfertility is difficult to establish in many individual patients, but as a group, patients with fibroids have diminished fertility and are more likely to have pregnancy-related complications than women without fibroids (Klatsky et al. 2008). The role of uterine embolization in this group of patients is secondary to myomectomy in most patients who have not had prior therapy and who have a strong desire for pregnancy. In a randomized trial, women with fibroids interested in pregnancy were treated with either embolization or myomectomy, with better reproductive outcomes in the first 2 years after treatment among the patients treated with myomectomy (Mara et al. 2008). UAE may have a role in patients who are poor surgical candidates, who have had prior pelvic surgery, or who have a strong desire to avoid surgery. There is a much more detailed discussion of fertility and treatment options in the chapters on fertility.

3 Contraindications

3.1 Practice Guidelines

The contraindications to UAE have not been well-defined. While published practice guidelines have included contraindications, these have not been evidence-based. For example, the Society of Interventional Radiology published a policy and position statement on patient care and uterine artery embolization for leiomyomata in 2009 (originally published in 2004) (Andrews et al. 2009) that listed a range of potential contraindications, including immunocompromise, prior pelvic irradiation or surgery, adenomyosis, and serosal fibroids with a narrow attachment, all without clear evidence that these patients are at high risk. Even more conservative are the guidelines from the Society of Obstetrics and Gynaecologists of Canada, which state that since uterine embolization is known to have a very small but real chance of a complication leading to hysterectomy, UAE should not be offered to women who refuse hysterectomy (SOGC Clinical Practice Guidelines 2005). This begs the question of what options these patients might have, as most gynecologic procedures that might be alternatives to UAE have the same risk. Many of the recommendations in these guidelines have not been subjected to rigorous evaluation and, as is discussed in the sections below, there is some evidence gathering that embolization may be safe in some circumstances in which traditionally it has been avoided.

3.2 Pregnancy

Current pregnancy is one of the absolute contraindications and patients must be tested to exclude pregnancy before the procedure. As a pregnancy test is likely to be negative for the first few weeks of pregnancy, in ideal circumstances, the embolization should be performed within the first 10 days of the menstrual cycle, which would ensure that an early pregnancy is not present. Unfortunately, due to the irregularity of menstrual cycles in this population and the vagaries of scheduling, the ideal timing is often not practical.

3.3 Suspected Uterine or Adnexal Malignancy

Suspected uterine and adnexal malignancy should be evaluated before treatment. This often may be characterized on the MRI, but in some cases operative intervention is needed for diagnosis. The extent of the evaluation that should be performed has not been well-defined and depends on the level of suspicion. For masses that are highly suspicious for malignancy, the diagnosis should be clarified with biopsy (Fig. 3). There are several types of gynecological malignancy that might occur.

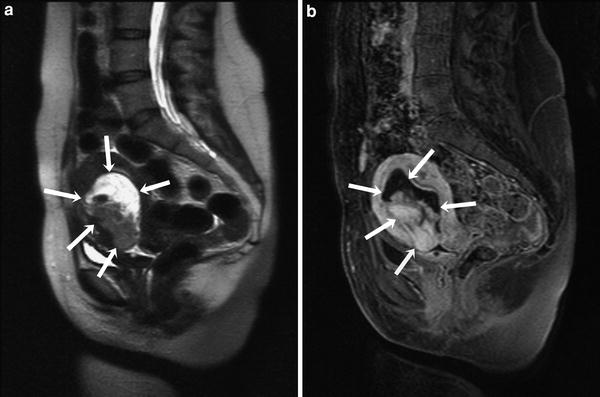

Fig. 3

Probable endometrial cancer. a Sagittal T2-weighted MR image of the pelvis demonstrating a markedly heterogenous mass (arrows) in the endometrial cavity in a 48-year-old woman with irregular menstrual bleeding. b Sagittal T1-weghted contrast-enhanced MR image showing very variable contrast enhancement. The mass is irregular in contour and internal architecture more suggestive of a neoplasm than a fibroid

First and perhaps most common is endometrial cancer. This would be an unusual malignancy in a premenopausal patient but must at least be considered in patients with atypical bleeding. Menorrhagia associated with fibroids usually results in longer and heavier menstrual cycles. Interperiod bleeding is infrequent. Endometrial malignancy and potential precursors such as endometrial hyperplasia with atypia are more likely to present with irregular intermenstrual bleeding. Imaging may show thickening of the endometrial lining. Endometrial sampling, either via pipelle biopsy or dilatation and curettage, is necessary for a definitive diagnosis.

Leiomyosarcoma is the malignant counterpart of leiomyoma, a rare malignancy with an incidence of 0.13 and 0.29 % among women being treated for presumed fibroids (Leibsohn et al. 1990). Differentiating a leiomyosarcoma from a fibroid may be difficult based on clinical history or imaging findings. Clinically, the presence of a “rapidly growing” fibroid has been suggested as a marker for possible leiomyosarcoma, but in a series 371 patients with rapidly growing fibroids, only one had a sarcoma (Parker et al. 1994). On MRI, these tumors typically present as a single or dominant mass with a distorted internal architecture and variable enhancement. In a small series, Tanaka et al. 2004 found that they may be characterized by greater than 50 % high signal on T2-weighted images and foci of increased signal on T1-weighted images, suggesting hemorrhage (Tanaka et al. 2004). Unfortunately these findings are not specific. Unless there is local invasion of the myometrium or endometrium and adenopathy, it may be difficult to distinguish a sarcoma from an atypical benign leiomyoma. A high index of suspicion based on the imaging findings of the mass itself is needed to detect these lesions. If a fibroid is bizarre in architecture or shows a markedly atypical enhancement pattern, leiomyosarcoma should be considered, and the patient should be referred to a gynecologist or gynecologic oncologist for definitive diagnosis.

Ovarian cancer, usually presenting as a cystic or mixed cystic and solid mass, is the most common adnexal malignancy encountered in this population. A complete description of the imaging findings is beyond the scope of this chapter and if a suspicious ovarian mass is identified, then UAE should be deferred until a diagnosis is completed.

3.4 Contrast Allergy

An allergy to iodinated contrast is a relative contraindication, although these reactions may be less likely with intraarterial use. In some cases, gadolinium-based contrast may be used as a substitute, although the volume of contrast needed may exceed the safe dose of gadolinium.

The risk of a reaction may be minimized with preprocedural administration of corticosteroids. Current American College of Radiology Guidelines provide recommended regimens for prophylaxis, including oral corticosteroids and oral diphenhydramine (ACR Committee on Drugs and Contrast Media 2010). Two options for oral corticosteroids are suggested: 50 mg of prednisone 13, 7, and 1 h before the procedure, along with 50 mg of diphenhydramine or 32 mg of methyprednisolone 12 and 2 h before the procedure, along with the diphenhydramine. All patients undergoing uterine embolization should have secure intravenous access and oxygen available in the room, as well as immediate availability of a resuscitation cart. In patients with severe contrast allergy, the procedure may best be completed with anesthesia assistance to ensure appropriate airway support.

3.5 Pelvic Infection

Active uterine or adnexal infection is also a UAE contraindication as it may predispose to fibroid infection. If unchecked, fibroid infection can lead to sepsis, so clearly avoiding infection is important. Embolization is safe after the infection resolves with appropriate therapy. Endometrial infections prior to UAE would be very atypical and the most likely concern would be active pelvic inflammatory disease. This clearly requires resolution prior to UAE.

Less certain is when there has been previous infection or possible infection. This would be most commonly seen in a patient with hydrosalpinx. Early in the UAE experience, reported a possible infection post-UAE in a patient with hydrosalpinx (Goodwin et al. 1997) . Since that time, there has been a concern that the presence of hydrosalpinx might predispose to uterine infection after the procedure. There have been no further published studies on this issue. Hydrosalpinx presents with varying degrees of severity and chronicity. In a patient with a long-standing hydrosalpinx and no clinical evidence of infection, infection is unlikely to be present. The use of prophylactic antibiotics directed toward chlamydia and other potential tubal pathogens may be appropriate. In our practice, we use either oral doxycyline for 5 days prior to the procedure or a single intravenous dose of ceftriazone immediately before the procedure to provide a margin of safety in patients presenting with hydrosalpinx, although there are no controlled trials assessing the efficacy of antibiotics in this setting.

Another concern for infection is in those patients with intrauterine devices in place. These have routinely been considered as a contraindication to embolization, as they are feared to predispose to infection (Steen and Shapiro 2004). While the risk is likely very low in a population with a low prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases, it has been a concern for interventionalists. A recent study of 20 women undergoing uterine embolization with intrauterine devices found no increased risk of infection (Smeets et al. 2010

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree