Chapter Outline

There are different ways to perform an upper gastrointestinal (GI) barium study. In Chapter 2 , a technique was described that relies primarily on barium filling and mucosal relief (i.e., single-contrast technique). The method described in this chapter relies primarily on double contrast, although it is actually a biphasic technique that combines the advantages of single and double contrast. Individual fluoroscopists generally develop their own routines and variations. Nevertheless, the techniques discussed in this chapter are representative of a reasonable approach for performing double-contrast upper GI examinations.

General Principles

Double-contrast upper GI studies are designed to coat the mucosal surface with a thin layer of high-density barium while the lumen is distended with gas. The routine examination should include the thoracic esophagus, stomach, and duodenum as far as the duodenojejunal junction. The examination should be performed quickly to maintain optimal mucosal coating and prevent barium filling of the duodenum and small bowel from obscuring the stomach. It is not critical that each segment of the upper GI tract be examined in anatomic sequence. For example, it may be preferable to examine the antrum, pylorus, and duodenum before significant overlap with the small bowel has occurred. Similarly, when the pharynx needs to be evaluated, it may be preferable to perform this portion of the examination after the upper GI study has been completed. The technical and logistic details of the examination should also be tailored for individual studies based on the following: (1) the patient’s presenting symptoms; (2) the anatomic configuration of the esophagus, stomach and duodenum; and (3) the specific abnormalities observed at fluoroscopy.

Components

Barium Suspensions

For the double-contrast examination, we use high-density 250% w/v barium (E-Z-HD; Bracco Diagnostics, Monroe Township, NJ). The preparation of the barium suspension is critical because slight deviations in concentration may impair the quality of mucosal coating and create artifacts.

Effervescent Agents

Various effervescent agents are available in powder, granular, or liquid form. These agents release 300 to 400 mL of carbon dioxide on contact with fluid in the stomach.

Hypotonic Agents

The use of a hypotonic agent to relax the stomach and duodenum results in a better examination and allows the examiner additional time to achieve optimal mucosal coating. In the United States, the only suitable hypotonic agent is glucagon; an intravenous injection of 0.1 mg usually produces transient hypotonia of the stomach. In some patients, this hypotonic effect delays barium filling of the duodenum for several minutes, prolonging the examination. Anticholinergic agents may also be used to induce GI hypotonia, but these agents are contraindicated in patients with glaucoma, cardiac disease, and urinary retention.

Radiographic Components

In modern radiology practice, fluoroscopic GI examinations are generally performed with digital fluoroscopy and spot imaging. The advantages of a digital system—better contrast resolution, shorter exposures, and faster examinations—more than compensate for a small decrease in spatial resolution. The study is reviewed at a computer workstation, with postprocessing of the images for optimal interpretation. Afterward, the studies are archived on a central picture archiving and communications system (PACS), enabling easy electronic retrieval of prior studies for comparison with the current examinations.

Routine Technique

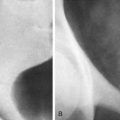

Selected views from a normal double-contrast upper GI study are shown in Figure 17-1 . We begin with a short review of the patient’s history and symptoms. Special care is taken to ask whether the patient has had any previous surgery and whether the patient is taking any ulcerogenic medications. The examination usually starts with an intravenous injection of 0.1 mg of glucagon. After this injection, the patient ingests an effervescent agent followed by 10 mL of water to facilitate the release of carbon dioxide in the stomach. The patient then stands in the left posterior oblique position and is asked to gulp the contents of a cup containing 120 mL of high-density barium as rapidly as possible while double-contrast views of the esophagus are obtained in rapid succession. These views should include the distal esophagus and gastroesophageal junction. Barium is often seen cascading into the gas-filled stomach (see Fig. 17-1A ).

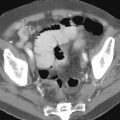

After the esophagus has been examined, the table is lowered into the horizontal position, and the patient is turned a full circle to achieve adequate barium coating of all surfaces of the stomach. Supine, left posterior oblique, and right posterior oblique views of the gastric antrum and body are then obtained (see Fig. 17-1B ). The patient is next placed in the recumbent right side down position for a double-contrast view of the gastric cardia and fundus (see Fig. 17-1C ). The patient is then placed in the semiupright, right posterior oblique position for a view of the high lesser curvature, upper body, and fundus (see Fig. 17-1D ) and then in the supine, left posterior oblique position for double-contrast views of the duodenal bulb and sweep (see Fig. 17-1E ). Flow technique is subsequently performed by slowly rotating the patient from side to side to manipulate a thin pool of barium over the posterior (dependent) gastric wall. Flow technique is extremely valuable for demonstrating shallow protruded or depressed lesions on the dependent surface ( Fig. 17-2 ).

After the double-contrast phase of the study has been completed, the patient is placed in a prone, right anterior oblique position and asked to take discrete swallows of a thin, low-density barium suspension to evaluate esophageal motility (see Chapter 18 ). The patient then rapidly gulps thin barium for single-contrast views of the optimally distended thoracic esophagus. Prone and upright compression views of the barium-filled stomach and duodenum are then obtained. Finally, the fluoroscopist tests for spontaneous gastroesophageal reflux or reflux induced by a Valsalva maneuver to increase intra-abdominal pressure. If there is no evidence of gastroesophageal reflux with this maneuver, a water siphon test is performed to increase the sensitivity of the fluoroscopic examination for reflux. Our routine double-contrast upper GI study is summarized in Table 17-1 .

| Position | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Upright, LPO | Esophagus, double contrast |

| Supine, LPO | Stomach, antrum and body, double contrast |

| Supine | Stomach, antrum and body, double contrast |

| Supine, RPO | Stomach, antrum and body, double contrast |

| Right side down lateral | Stomach, cardia and fundus, double contrast |

| Supine, LPO | Antrum, pylorus, duodenal bulb and sweep, double contrast |

| Supine and supine obliques | Antrum and body, flow technique |

| Semiupright, RPO | Stomach, high lesser curvature and fundus, double contrast |

| Prone, RAO | Esophagus, function and barium filling |

| Prone or prone, RAO | Antrum and duodenum, compression |

| Upright | Antrum, lesser curvature, and duodenum, compression |

| Recumbent | Test for gastroesophageal reflux |

Anatomic Considerations

Although the normal anatomy of the upper GI tract is well known, several anatomic variations that are particularly well demonstrated by the double-contrast technique should be stressed.

Esophagus

The normal mucosal surface of the esophagus is smooth and featureless ( Fig. 17-3A ). When the esophagus is partially collapsed, the normal longitudinal folds are seen as smooth, straight structures no more than 1 to 3 mm in width ( Fig. 17-3B ). In some patients, fine transverse folds may also be observed in the esophagus because of transient contraction of the longitudinally oriented muscularis mucosae ( Fig. 17-3C ). These folds are almost always found to be associated with gastroesophageal reflux. In contrast, focally spiculated transverse folds may be detected as a normal variant in the upper thoracic esophagus at the junction of the striated and smooth muscle near the level of the aortic arch ( Fig. 17-3D ); these are thought to result from localized weakening of the amplitude of peristalsis in this region. Finally, in older patients, small nodules may be visible on the mucosal surface of the esophagus because of glycogenic acanthosis, a common degenerative condition of no clinical significance ( Fig. 17-4 ).