BENIGN AND MALIGNANT CHONDROGENIC TUMORS OF BONE

KEY POINTS

- Chondroid lesions are uncommon in the head and neck.

- They do represent a significant percentage of skull base tumors.

- Some controversy still persists with regard to the terminology of chordomas and chondroid variants of chordomas, but this likely has no real clinical relevance with regard to medical decision making or prognosis.

- Pathology of bone lesions should almost always be read together with the imaging findings to produce the best diagnoses and optimize medical decision making.

Tumors of bone may come from one of several cell lines, and more than one line of differentiation may be present in any particular benign or malignant bone tumor. Those arising from the chondrocyte that may be encountered in the head and neck are discussed here. Fibro-osseous, dental-origin, and osteoid tumors, including osteochondromas, and tumors arising from osteoclasts are discussed separately in Chapters 38, 40, 41, and 99. The appearance of various matrices is discussed in Chapter 12.

CHONDROMAS AND CHONDROSARCOMAS

Clinical Perspective and Pathology

Chondromas and chondrosarcomas of the head and neck region are less common than the already rare osteogenic lesions.12 It is probably best to consider any chondroid origin mass a low-grade malignancy with at least the potential for local recurrence.1–4 Chondromas tend to arise from the nasal cartilages (Fig. 39.1), ethmoid bones, skull base (Figs. 39.2–39.4), larynx (Figs. 39.5–39.7), and trachea1,5,6 (Fig. 39.8). Chondrosarcomas seem to most frequently involve the skull base around the petroclival junction and occasionally elsewhere (Fig. 39.9), mandible and, maxilla, but frankly malignant tumors may arise in all sites listed above.7 In addition, the chondroid variant of chordoma can mimic a chondroma on pathologic examination alone.8,9 Peak age incidence is 20 to 40 years of age; however, the age range of occurrence is wide.1

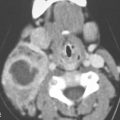

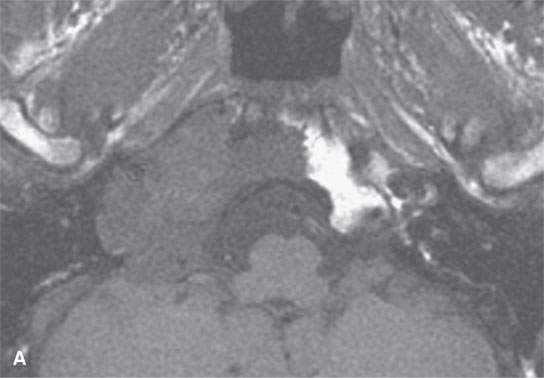

FIGURE 39.1. Magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography (CT) study of a patient with a chondrosarcoma of the nasal septum. A, B: Contrast-enhancedT1-weighted images show some enhancement of a generally low signal intensity mass. The relatively low signal intensity areas are likely due to a variably mineralized chondroid matrix. C: T2-weighted image showing that some areas of the matrix are bright and others are somewhat darker in a stippled manner due to a variably mineralized chondroid matrix. D: CT study shows ringlike calcification, which is typical of cartilage matrix calcification.

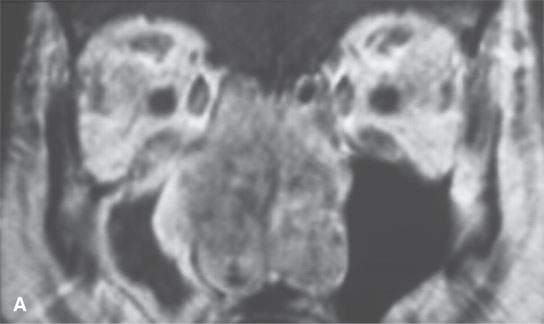

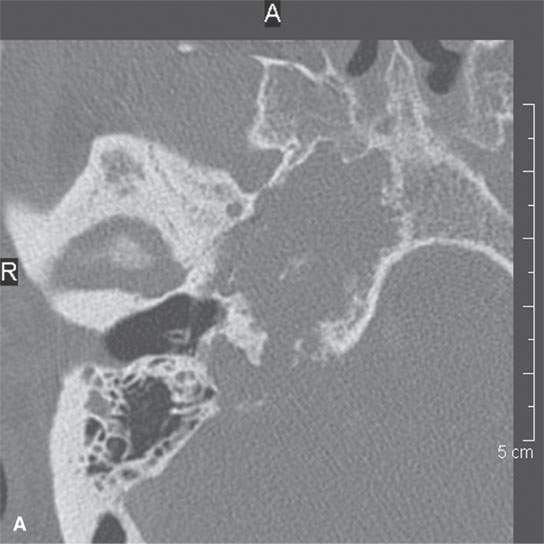

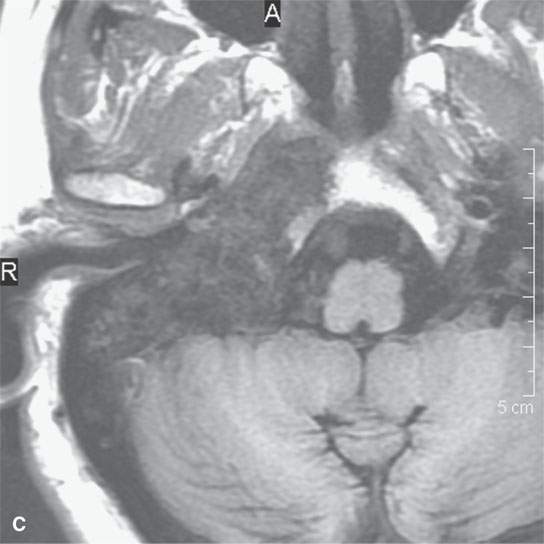

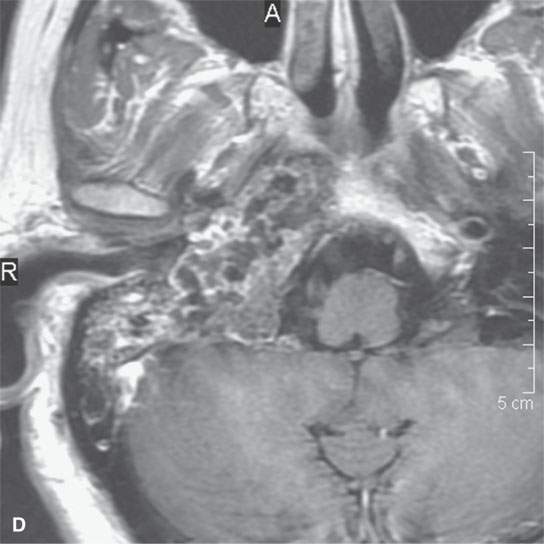

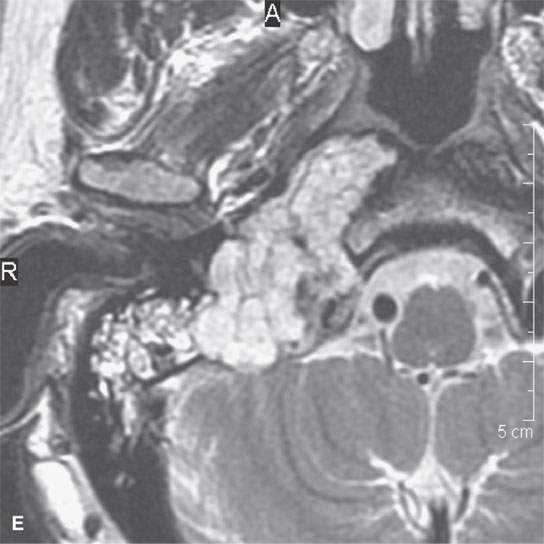

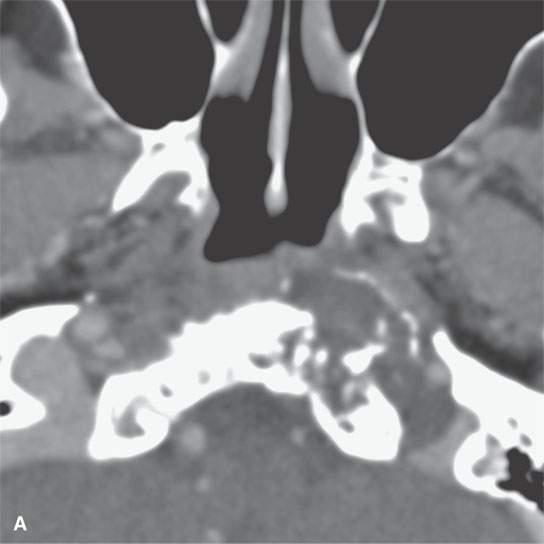

FIGURE 39.2. Chondrosarcoma of the petrous apex seen on computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance study. A, B: Contrast-enhanced CT study. In (A), an aggressive bony destructive pattern is illustrated. In (B), note the relatively low density of the tumor matrix, which in this patient is not significantly mineralized. C: Non–contrast-enhanced T1-weighted (T1W) image showing the tumor to be obviously less intense than muscle. D: Contrast-enhanced T1W image shows a somewhat bubbly enhancement pattern. E: T2-weighted (T2W) image showing an almost multiloculated bubbly appearance to the chondroid matrix. The chondroid tumor matrices are frequently of increased signal intensity approaching that of cerebrospinal fluid on T2W images.

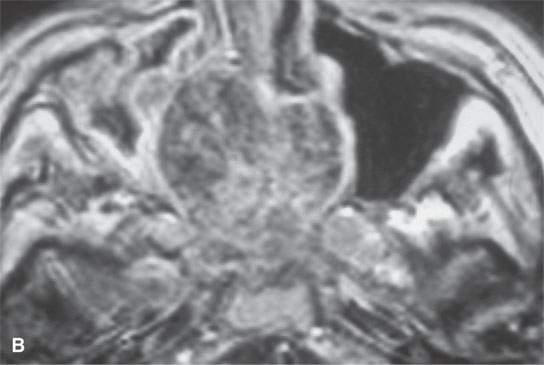

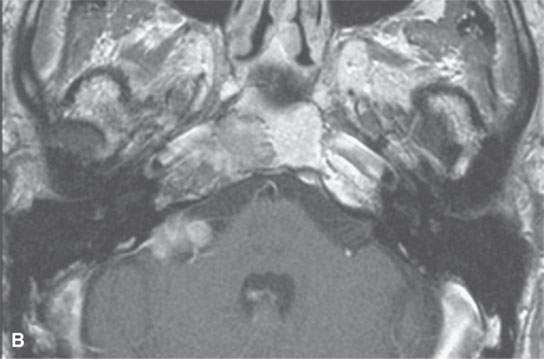

FIGURE 39.3. Magnetic resonance study of a patient with chondrosarcoma of the petrous apex and central skull base. A: T1-weighted (T1W) image that shows tumor less intense than brain and perhaps slightly less intense than muscle. B: Contrast-enhanced T1W image shows some elements of the tumor with homogeneous enhancement and others less enhancing. C: This image shows some zones of the tumor to be bright and some relatively dark, attesting to the variable consistency of the matrixes seen in chondrosarcoma.

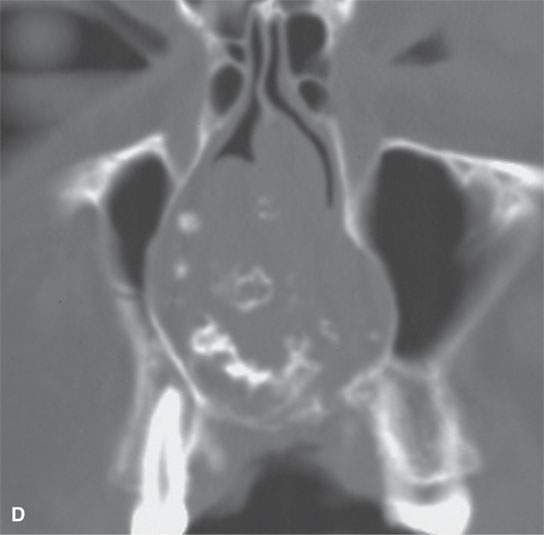

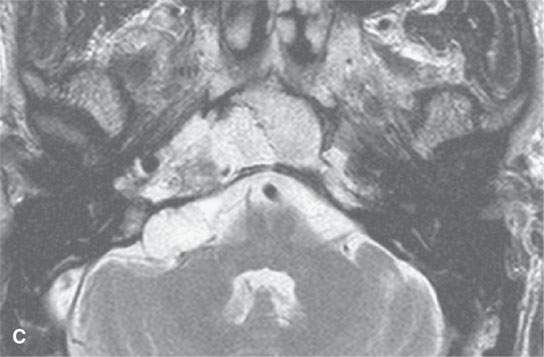

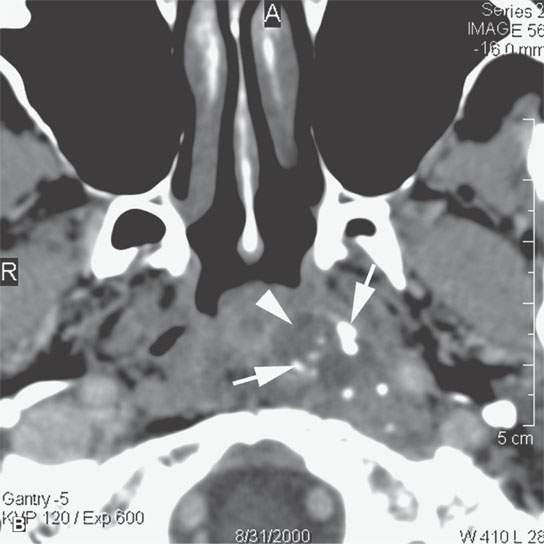

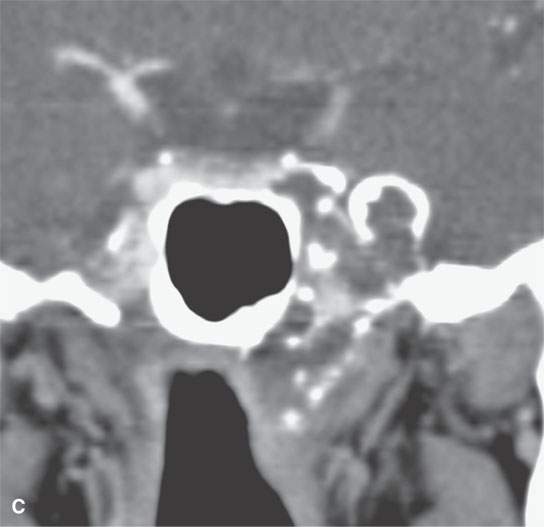

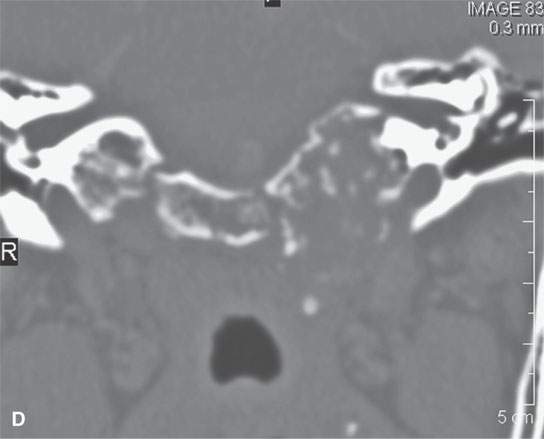

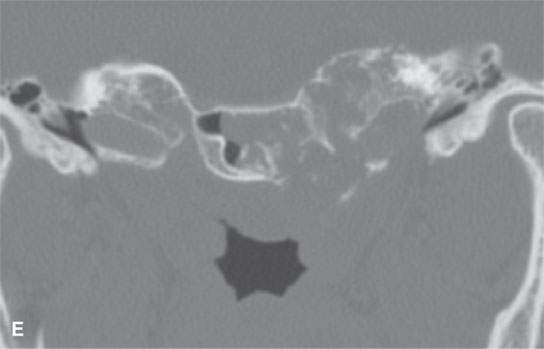

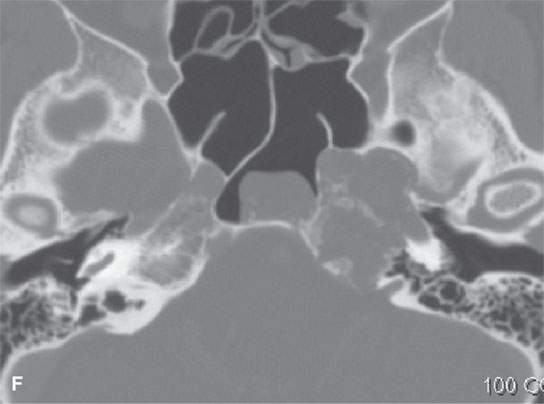

FIGURE 39.4. Computed tomography of a chondrosarcoma of the petrous apex and central skull base. A–C: Contrast-enhanced soft tissue views show some minor enhancement within a generally low density tumor. The lesion shows some evidence of likely regressive remodeling of surrounding bone. In (B), the low density nature of the matrix where it is not calcified (arrowhead) can be differentiated from zones of matrix calcification (arrow). In (C), the overall variability of matrix calcification and enhancement can be appreciated. D–F: Bone windows demonstrate the pattern of bone destruction and matrix calcification present in this type of lesion.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree