BENIGN AND MALIGNANT EPITHELIAL TUMORS: LESIONS OF MUCOSAL ORIGIN

KEY POINTS

- Mucosal cancers are the most common malignancies in the head and neck.

- The imaging appearance of these cancers on computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging are fairly predictable.

- Evaluation of these lesions requires a knowledge of the natural history in general and their tendencies to spread locally, along neurovascular bundles, and to regional lymph nodes.

Benign and malignant epithelial neoplasms are by far the most common in the head and neck region. Squamous cell carcinoma (epidermoid carcinoma) alone accounts for about 85% of malignancies of the extracranial head and neck. Another 5% are adenocarcinomas arising from glandular elements in the mucosa, accessory salivary tissue, or major salivary glands discussed in Chapter 22. Most of the benign tumors encountered in the head and neck region will also be of mucosal origin, making this category, by far, the largest source of neoplasms.

This chapter takes a pathologic point of view of tumors of mucosal origin. Skin sources are considered in conjunction with tumors of cutaneous origin in Chapter 24. Each tumor type is considered in terms of its occurrence at various head and neck sites. Also, the particular effect of a neoplasm’s spread pattern, natural history, and cellular structure have on its computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance (MR), and ultrasound (US) anatomic appearance and its physiology as reflected on metabolic imaging studies such as fluorine-18 2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) are considered. In general, malignant mucosal lesions are FDG avid. The clinical and imaging implications of a particular type of tumor at a specific anatomic location are presented in site-specific discussions.

When evaluating the malignant mucosal tumors, the appearance natural history of the lesion must be understood and appreciated on imaging with regard to its local extent, including soft tissue, bone and cartilage invasion, potential routes of perineural spread, and spread to regional lymph nodes.1 These are issues discussed in Chapter 21 in general and in discussions of site-specific occurrence.

BENIGN MUCOSAL TUMORS

Papillomas

The term papillomas is often applied indiscriminately to any elevated growth on mucosal surfaces. This is incorrect usage of the term, and here the term refers to true neoplasms and not inflammatory, fibroepithelial polyps (Fig. 23.1). The papillomas of the oral cavity and larynx are of interest to the radiologist only in the most advanced cases wherein the airway is threatened or there may be malignant changes in the papillomas (Fig. 23.2). In general, these lesions are evaluated by direct inspection and endoscopy and in many cases are not imaged. Sinonasal tract papillomas are another matter. Some speculate that the difference in biologic behavior and age range between the sinonasal and laryngeal disease is based on the uniqueness of the “schneiderian membrane” that forms the sinonasal mucosa except for the olfactory mucosa in the high nasal cavity.2,3 The schneiderian membrane is of ectodermal origin, whereas the rest of the upper respiratory epithelium is endodermal in origin. There are three histomorphologic papillomas recognized in the sinonasal region. These are categorized mainly on an anatomic basis: (a) keratotic lesions arising in the nasal vestibule; (b) inverted papilloma, from the lateral nasal wall; and (c) fungiform or septal papilloma. The only one of major importance on CT and MR is inverted papilloma, which is discussed in detail in conjunction with sinonasal tumors in Chapter 89.

FIGURE 23.1. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of a patient with fibrovascular reactive polyps in the larynx originally thought to be neoplastic or possibly a hemangioma.

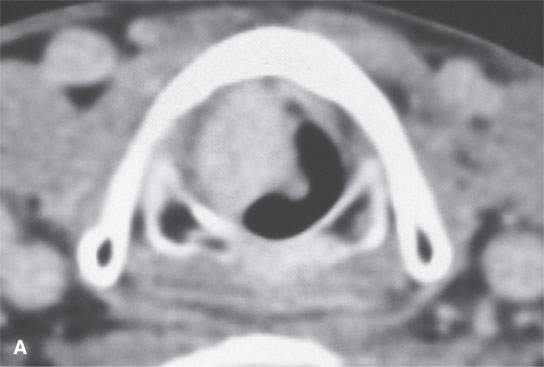

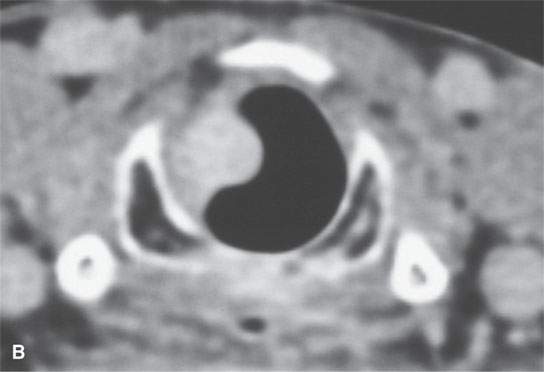

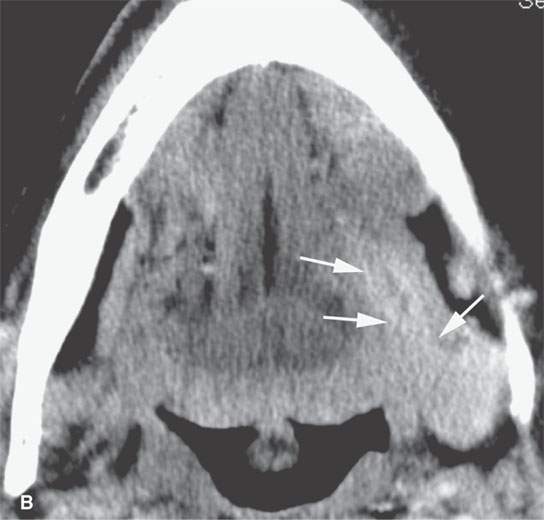

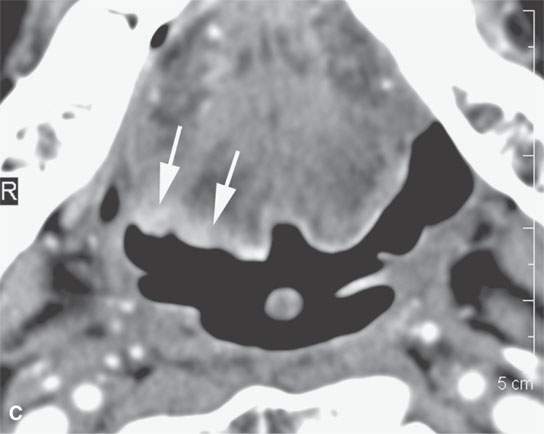

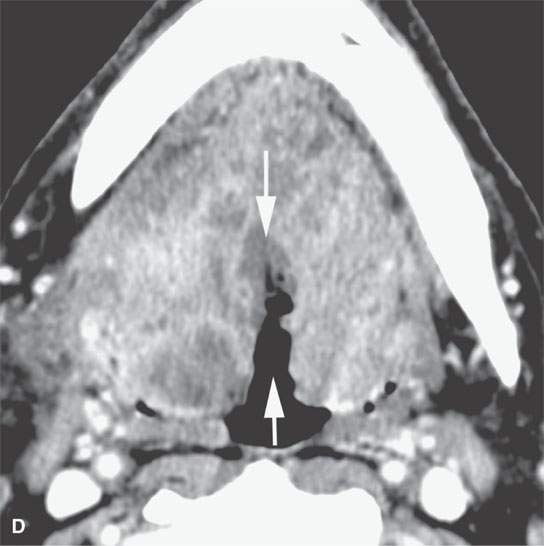

FIGURE 23.2. Computed tomography (CT) of a patient with papillomatosis of the upper and lower airway. A: CT allows for a survey of the entire airway and can obviate endoscopy and bronchoscopy in some patients. B, C: The polyps thicken the mucosa (arrows in B and arrowheads in C) and weaken the airway by growing into its cartilaginous and membranous walls.

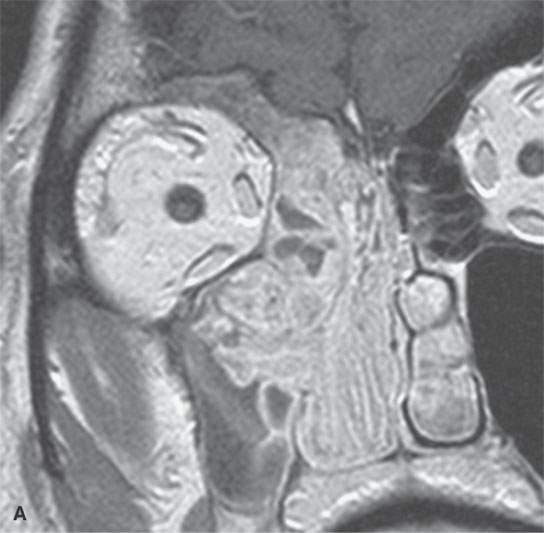

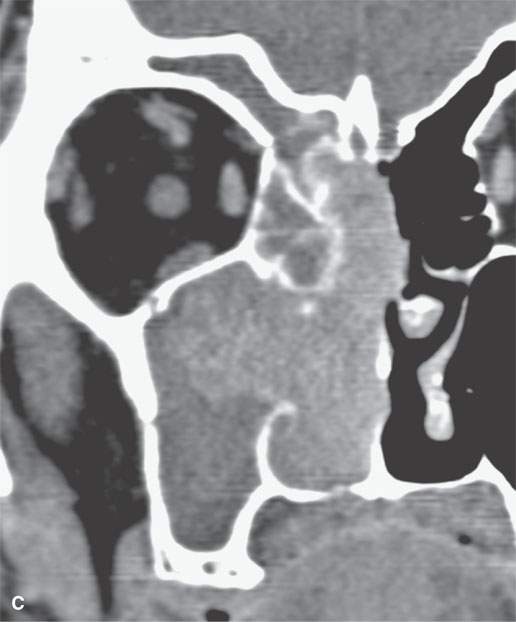

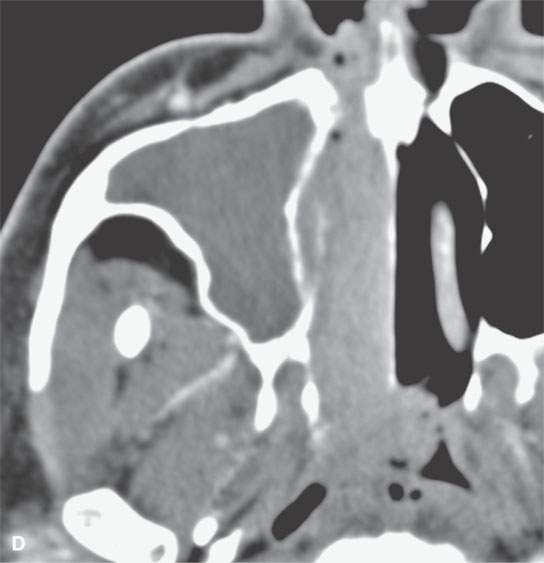

Inverted papilloma is a descriptive term based on the microscopic appearance of the lesion. The neoplastic epithelium grows into the underlying stroma, causing the stroma to become heaped up over the epithelial nidus. The stroma may be anywhere from loose and edematous to compact and fibrous. On CT, the lesions usually approximate muscle density (Figs. 23.3 and 23.4). Sometimes, they appear obviously hyperdense to muscle, with some areas so dense that they appear calcified or even ossified. This may be due to associated desiccated secretions. Calcification is rarely a prominent histopathologic feature of these lesions. Chronic reactive, sclerotic bony changes and adjacent bony demineralization in the bone surrounding the middle meatus are common but not specific CT features (Fig. 23.4).

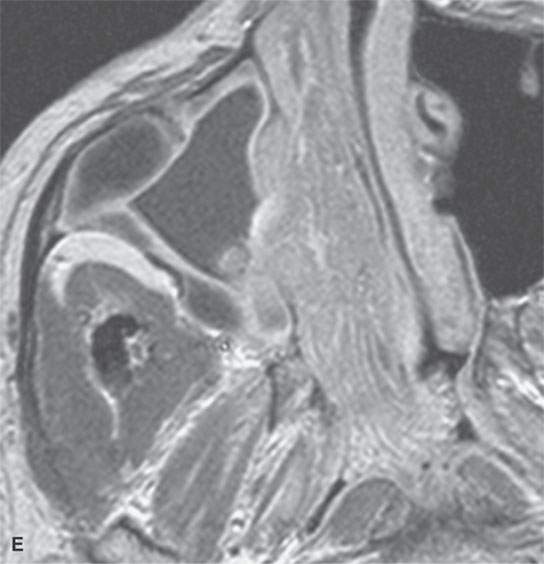

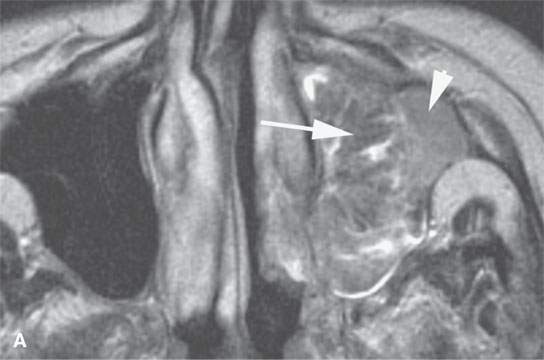

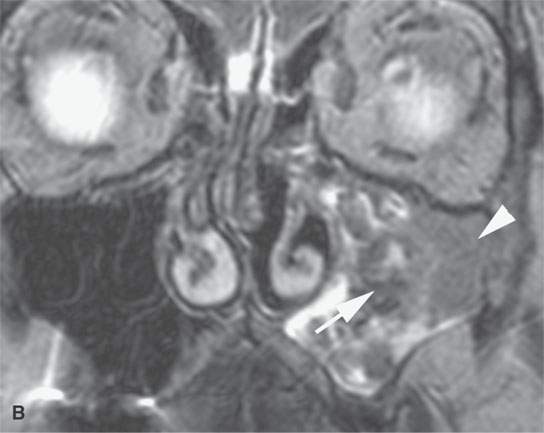

FIGURE 23.3. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) in a patient with inverted papilloma showing the typical frondlike growth pattern and the ease of differentiating the tumor from obstructive changes of which both are more easy to recognize on MRI. A: Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted (T1W) image. B: T2-weighted image. C, D: Contrast-enhanced computed tomography. E: Contrast-enhanced axial T1W image showing that the mass does not invade the nasopharyngeal mucosa—a finding not so certain on the CT image in (D).

FIGURE 23.4. Non–contrast-enhanced computed tomography of a patient with an inverted papilloma showing impacted secretions (arrowhead) and fairly typical reactive bony changes (arrow).

On T1-weighted images, inverted papillomas may be slightly hypointense to slightly hyperintense to muscle.4 On T2-weighted images, inverted papillomas will be isointense to slightly hyperintense to muscle and might well be brighter, reflecting the previously described variations in stromal composition4(Fig. 23.3).4 On contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT), generalized mild enhancement is possible. T2-weighted and contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance (CEMR) images will often show an infolded, frondlike general morphology not difficult to distinguish from standard inflammatory polyps (Fig. 23.3). A departure from this morphology may suggest a more aggressive component of the tumor (Fig. 23.5).

FIGURE 23.5. T2-weighted images show a typically benign frondlike pattern of an inverted papilloma medially (arrows) but a more homogeneously solid portion laterally (arrowheads) that was a carcinoma.

Inverted papillomas are treated surgically with wide local excision.5 They tend to recur and are locally infiltrative; 10% to 15% of these lesions will show some malignant change.6 Those with malignant change will take on the appearance of a typical squamous cell carcinoma described later in this chapter.6

MALIGNANT TUMORS OF EPITHELIAL ORIGIN

Squamous Cell (Epidermoid) Carcinoma

Squamous cell (epidermoid) carcinoma is by far the most common variety of cancer affecting the upper aerodigestive tract and neck. Its relationship to smoking and alcohol use is now well established.7,8–9 In the adult population, roughly 85% of all head and neck cancers will be of squamous cell origin. The salivary glands, thyroid gland, hard palate, and orbits are the only sites where squamous cell carcinoma is not the predominant oncologic problem. Much of the emphasis on malignant tumors at specific sites in the following discussions will therefore be on the natural history and spread patterns of squamous cell carcinoma at various head and neck locations.

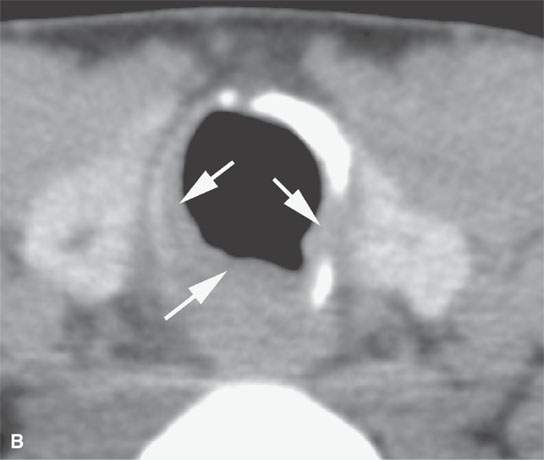

The more well-differentiated tumors will usually grow as a well-defined sometimes oval mass (Fig. 21.21A), with displacement of surrounding tissue or locally infiltrative margins. The main growth tendency, however, is to grow along the mucosal surface and then deeper. On non–contrast-enhanced computed tomography, their density is roughly equivalent to muscle. With contrast enhancement, the density of squamous cell carcinoma varies considerably from lesion to lesion, showing little or no change to marked enhancement sometimes depending on the degree of ulceration that might be present (Figs. 21.3, 21.13, 21.15, and 23.6). Exuberant enhancement may be related to the tumor itself and peritumoral reactive changes or inflammation due to secondary infection (Fig. 23.7). The latter is more common in ulcerative tumors. Necrosis of the primary tumor is uncommon in the absence of ulceration or treatment, but it does occur.

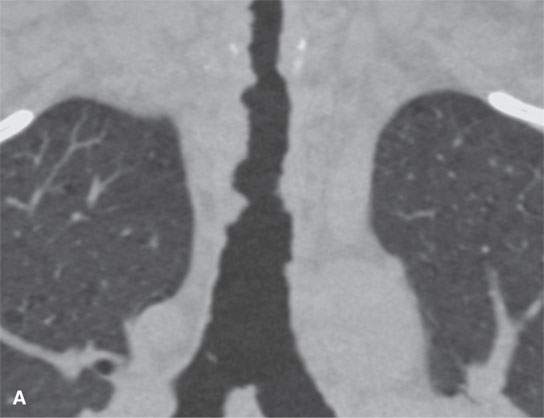

FIGURE 23.6. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography showing variability in enhancement, depth of invasion, and ulceration in three patients with squamous cell carcinoma (SCCA). A, B: A relatively superficial but clinically ulcerated floor of the mouth cancer resulting in fairly brisk enhancement of the superficial part of the tumor (arrows) and deeper in the floor of the mouth (arrowheads). C: Superficial minimally enhancing SCCA (arrows). D: Large-volume deeply infiltrating tumor with a very deep central ulcer and a mixed enhancement pattern.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree