BENIGN AND MALIGNANT OSTEOGENIC TUMORS OF BONE

KEY POINTS

- Osteomas and exostoses are usually of no consequence unless they occlude a sinus or create a cosmetic or functional problem or are multiple and possibly syndromic.

- Osteomas and osteochondromas can mimic masses of some other origin.

- Bone origin lesions are usually better evaluated with computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging is used adjunctively when necessary.

- Pathology of bone lesions should almost always be read together with the imaging findings to produce the best diagnoses and optimize medical decision making.

Tumors of bone may come from one of several cell lines, and more than one line of differentiation may be present in any particular benign or malignant bone tumor. Those arising from the osteocyte that may be encountered in the head and neck are discussed here. Fibro-osseous, dental-origin, chondroid, and osteoid tumors and tumors arising from osteoclasts, metastases, and bone cysts are discussed separately in Chapters 39–42 and 99.

OSTEOMA (EXOSTOSIS)

Clinical Perspective and Pathology

Osteomas are benign growths of mature bone.1–3 The nature of the osteoid matrix is described in more detail in Chapter 12. In the head and neck region, osteomas involve the skull, facial bones, and neck and clavicle (Figs. 38.1–38.3). Most are inconsequential. They may be properly differentiated clinically from tori and reactive bone changes, such as the cold water–induced exostoses of the external auditory canal and others, or just lumped with those same common processes involving mature bone proliferation (Fig. 38.2). Importantly, some present as masses that would be more ominous, and imaging can drastically alter the diagnostic and therapeutic process (Fig. 38.3).

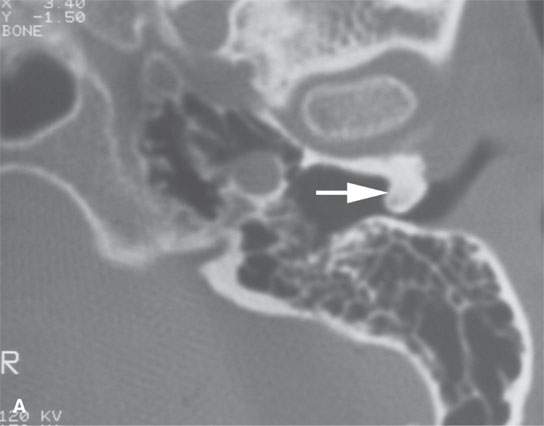

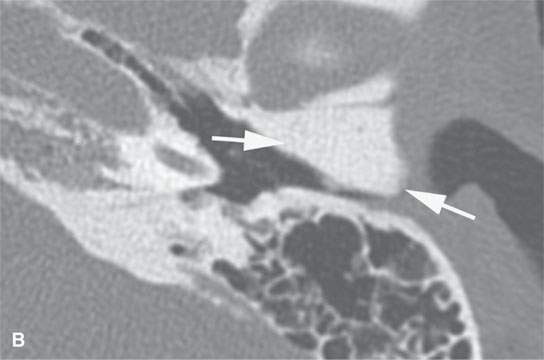

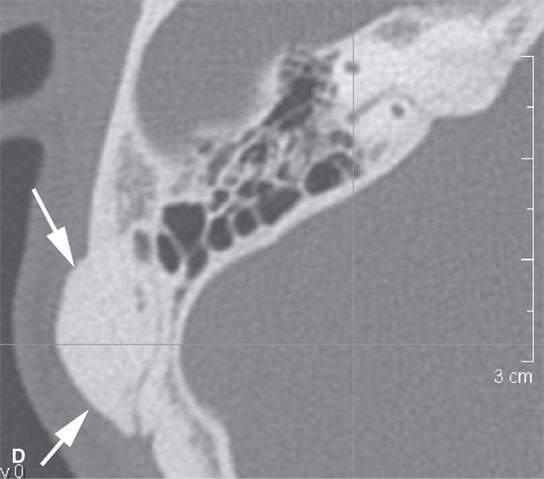

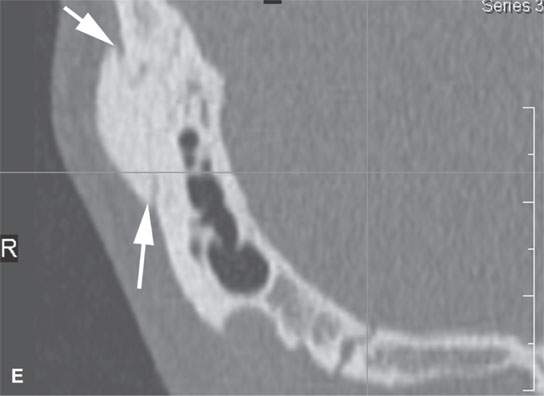

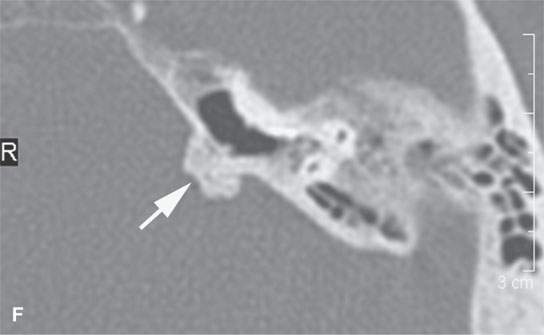

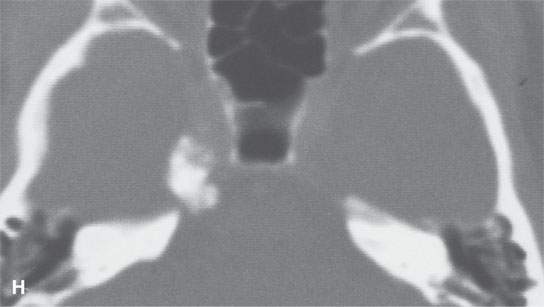

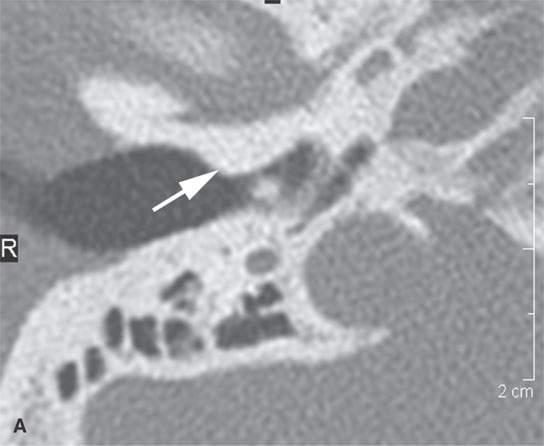

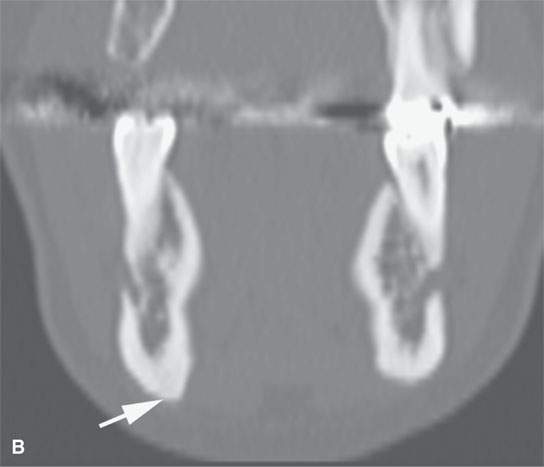

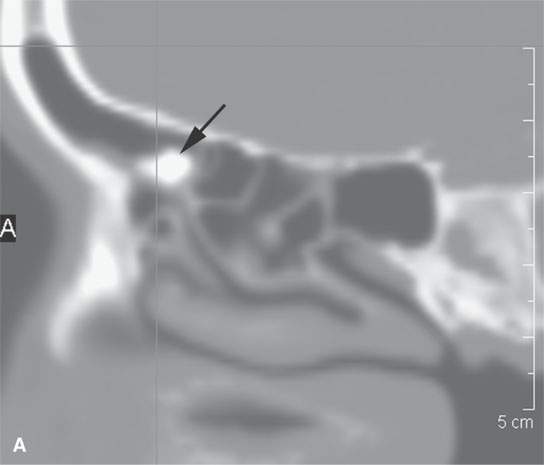

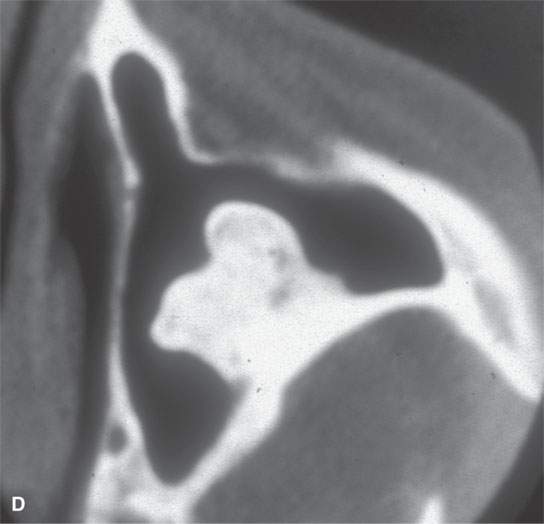

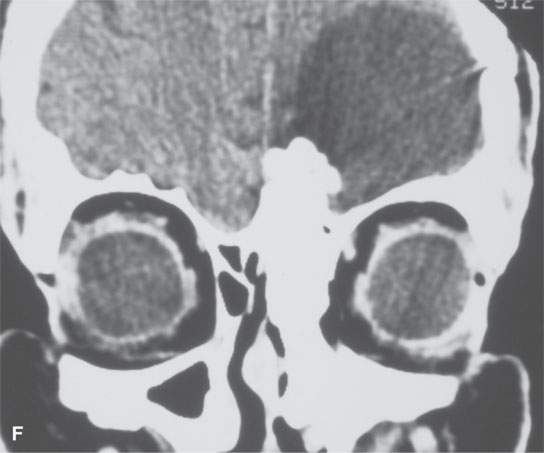

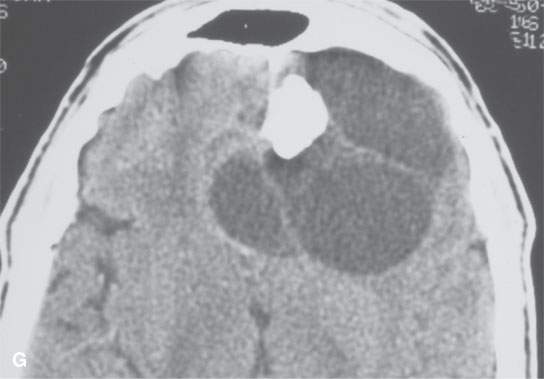

FIGURE 38.1. Various osteomas or benign exostoses. A: A localized exostosis of the external auditory canal (arrow). B: A large, occlusive osteoma of the eternal auditory canal (arrow) not related to cold water exposure. C: Coronal section of the same osteoma (arrow) seen in (B). D, E: An osteoma broadly sessile in its growth pattern along the mastoid portion of the temporal bone (arrows). F: An incidentally discovered inconsequential osteoma of the petrous portion of the temporal bone (arrowhead). G, H: An osteoma of mature but less calcified matrix possibly responsible for presenting ipsilateral fifth cranial nerve symptoms. This could have represented an osteochondroma. This was before the days of magnetic resonance imaging, and a cartilage cap could not be demonstrated.

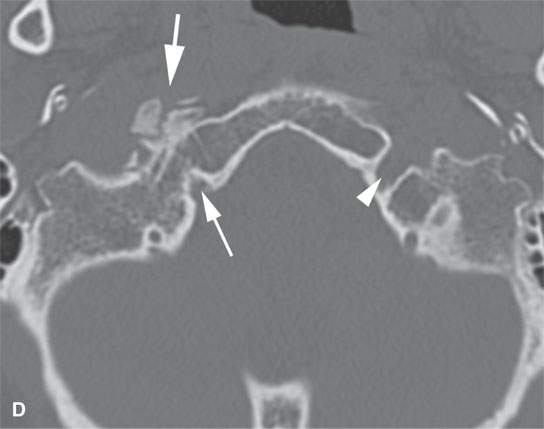

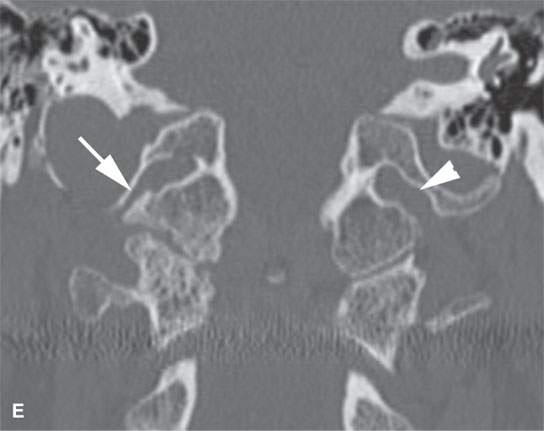

FIGURE 38.2. Several lesions having the appearance of an osteoma but possibly more likely to be reactive bony changes (“reactive osteomas”) that are locally productive mature bone changes due to local inciting cause. A: External auditory canal osteoma (arrow) that is due to chronic cold water exposure. B, C: Patient presenting with a mass along the submandibular region. This proved to be a small, likely reactive osteoma along the inferior margin of the mandibular body (arrow). Its reactive nature is suggested by the amount of focal sclerosis in association with the adjacent tooth root. D: The patient presenting with 12th cranial nerve dysfunction. The area of the hypoglossal canal on the right side is involved with an abnormal-appearing but mature bone. The appearance is somewhat suggestive of an osteoma and/or heterotopic bone formation (arrows). Its relationship to the hypoglossal canal is best appreciated by observing the normal hypoglossal canal on the opposite side (arrowhead). E: Coronal section correlating with that seen in (D). The hypoglossal canal is narrowed (arrow) compared to the opposite side (arrowhead) with bony changes that are obviously degenerative. This appearance mimics an osteoma but was likely bony productive change due to a prior accident. (NOTE:It was presumed that the 12th cranial nerve deficit was related somehow to the changes since no other cause was identified, and tongue weakness and neck and referred ear pain localized to this area was chronic, dating back to sometime after an accident to the cranial cervical junction region.)

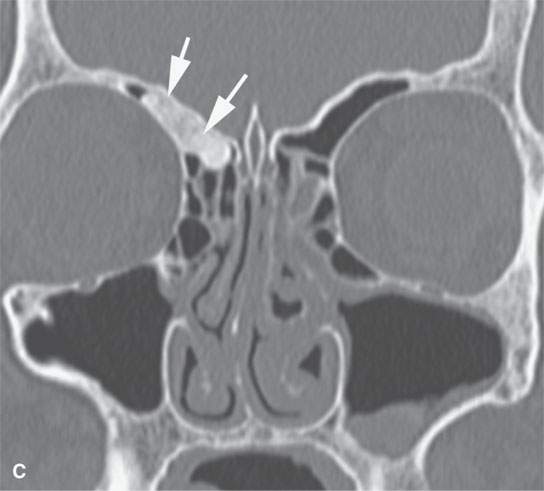

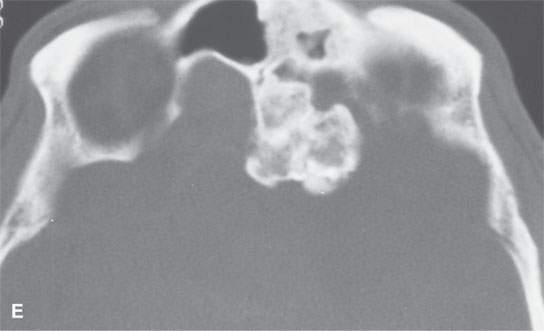

FIGURE 38.3. Several osteomas involving the paranasal sinuses. This is a very common location of osteomas. A: Inconsequential osteoma (arrow) in the region of the frontal recess found as an incidental finding. B: Osteoma in the frontal recess (arrow) with postobstructive changes evident in the frontal sinus (arrowhead). Endoscopic surgery resulted in resolution of chronic frontal sinus disease. C: Larger osteoma in the frontal recess region extending into the frontal sinus (arrows) composed of entirely mature bone but not producing any obvious obstruction. D: A somewhat lobulated sessile osteoma of the maxillary sinus producing no clinical problems. E–G: Osteoma of the frontal sinus causing secondary obstruction and mucocele.

Occasionally, osteomas produce symptoms that will be correctable with surgery. This is often the case in obstructing osteomas in the sinuses and external auditory canal (Figs. 38.1 and 38.3). Most often, they require no therapy.

Osteomas may arise in the medullary space or along the periosteum (Figs. 38.1–38.3). They may be sessile or attached to the bone of origin by a pedicle. Sinus osteomas are most common in the frontal sinus followed by the ethmoids, maxillary sinuses, and the sphenoid sinus in order of decreasing frequency (Fig. 38.3). Osteomas usually present between the ages of 15 and 40 years.3,4 Most are discovered incidentally. Multiple osteomas may be associated with Gardner syndrome.

Three types of osteoma are recognized: (a) osteoma eburneum with lamellated dense bone and haversian spaces (Fig. 38.1); (b) osteoma spongiosum composed of mature cancellous bone and, therefore, marrow spaces (Fig. 38.3A–C); and (c) osteoma durum lying somewhere in between the two just described1–5 (Fig. 38.3D,E).

Treatment is surgical. The need for surgery is based on the existing potential for complications such as sinus drainage occlusion. Sarcomatous changes do not occur in osteomas. Regrowth should not follow gross total removal.

Imaging Appearance

The computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance (MR) morphology may vary slightly based on these subtypes (Figs. 38.1–38.3). All show a mature bone pattern on CT.5 Fatty or hematopoietic marrow may be more apparent on MR than CT. Obviously densely compact bone shows up as a signal void on MR and may go unappreciated, especially when projecting into an aerated sinus.

OSTEOCHONDROMA

Clinical Perspective and Pathology

These may be either a developmental abnormality or true neoplasm. Osteochondroma can be called an osteocartilaginous exostosis. It is predominantly of osseus origin, but an osteochondroma will have a cartilage cap. It grows by enchondral ossification of this cartilage component (Figs. 38.4 and 38.5). These lesions are most common in the extremities.

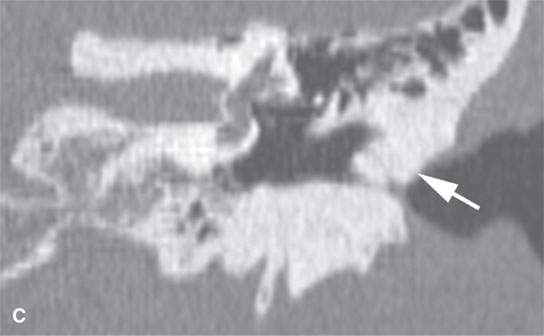

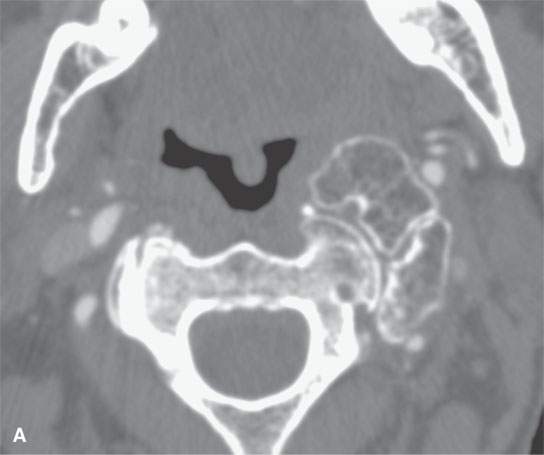

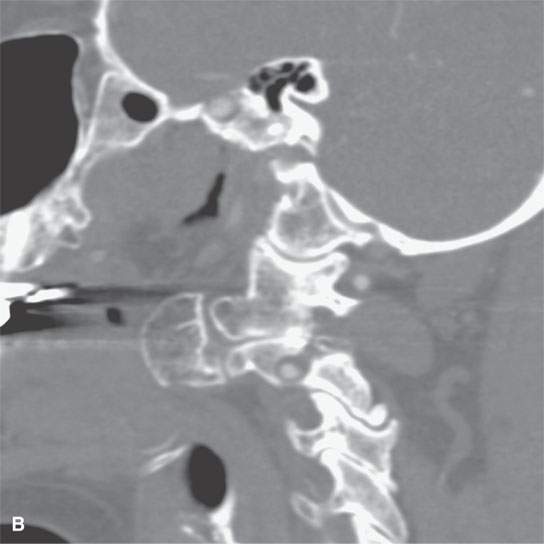

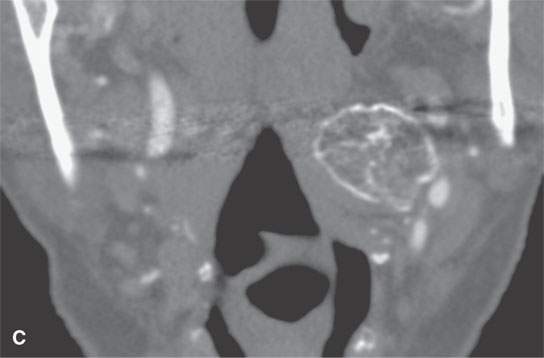

FIGURE 38.4. Patient presenting with parapharyngeal mass. This was noted on physical examination at the level of oropharynx and nasopharynx junction. A–C: Bony origin lesion believed to be an osteochondroma or heterotopic bone growing into the parapharyngeal space from the upper cervical spine. Magnetic resonance imaging was suggested to possibly identify a cartilaginous cap. The lesion was not painful. The patient elected to just be followed with imaging periodically as necessary if the lesion were to become painful.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree