BENIGN AND MALIGNANT TUMORS OF FIBROUS ORIGIN AND THE FIBROMATOSES

KEY POINTS

- Fibrous-origin processes often appear very infiltrating, more so than malignant neoplasms, but are actually benign.

- The imaging appearance of fibrous tissue on magnetic resonance imaging and the fibromatoses on magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography can be quite suggestive of those processes as a diagnosis.

- The fibrotic process can be reactive (granulation tissue) as opposed to neoplastic and especially whenever fibrovascular can mimic benign and malignant tumors.

- Infantile torticollis is not the same as fibromatosis colli, and fibromatosis colli must not be mistaken for a sarcoma.

THE FIBROCYTE

The fibrocyte participates in both reactive and neoplastic processes in the body, and reactive changes can be associated with inflammatory or neoplastic conditions. The histologic crossover seen in these processes can lead to diagnostic and management errors. For example, certain neurogenic tumors may be difficult to distinguish from leiomyosarcomas or aggressive fibromatosis because of an associated fibrous reaction. Also, a pseudosarcomatous fibrous reactive change can cause inflammatory nasal polyps to be mistaken for a malignancy. Often, a fibromatous tumor must be viewed with its clinical context, as well as histology, to determine just how aggressive it is likely to be. Most of the fibromatous lesions that present for imaging are best thought of as at least locally aggressive tumors with a tendency to recur locally and have limited metastatic potential. The age of the patient and histopathologic factors will then enter into the determination of the degree of aggressiveness and the best treatment plan.

FIBROMATOSES (DESMOID TUMORS) INCLUDING FIBROMATOSIS COLLI AND INFANTILE TORTICOLLIS

Clinical Perspective and Pathology

The fibromatoses run a gamut from the keloid to highly cellular fibroproliferative masses that may approach frank neoplasia in appearance (Figs. 37.1–37.8). These processes arise from muscular aponeuroses. The fibromatoses are proliferative fibrous lesions, also known as desmoid tumors, with a strong tendency to recur following surgery. The head and neck fibromatoses tend to occur mainly in children and young adults and usually present before 50 years of age. They may be subcategorized by age and degree of aggressiveness.

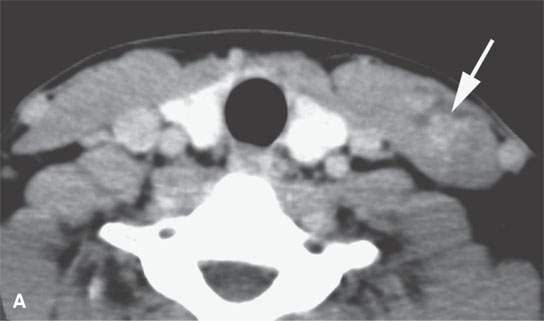

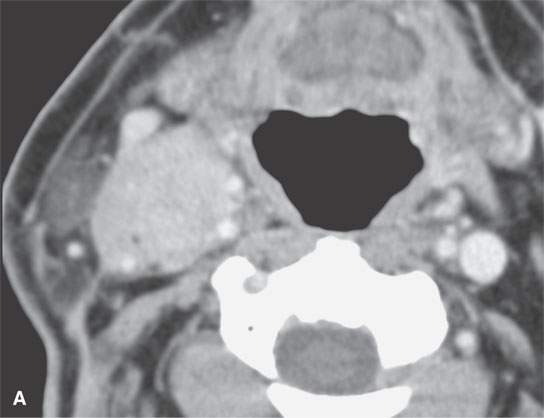

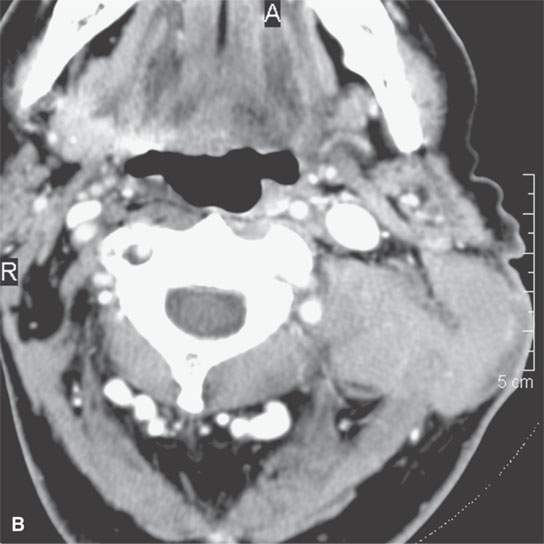

FIGURE 37.1. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography study of a patient with desmoid tumor of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. A: The muscle is slightly enlarged shows an indistinct pattern of enhancement (arrow) and low density. B: More inferiorly, there is a largely low density mass with marginal enhancement. This internal morphologic pattern is somewhat unusual, but this was confirmed to be a desmoid tumor.

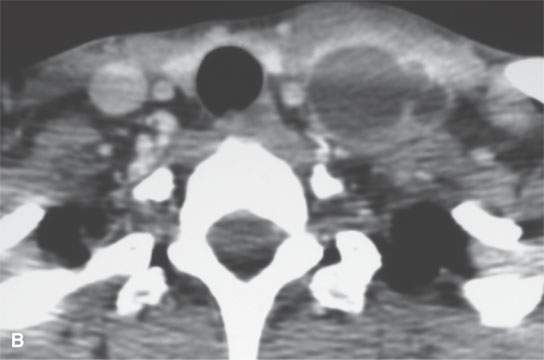

FIGURE 37.2. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography in a patient with a desmoid tumor of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. The mass infiltrates the muscle and more superficial soft tissues and is fixed to the skin with overlying skin thickening (arrows).

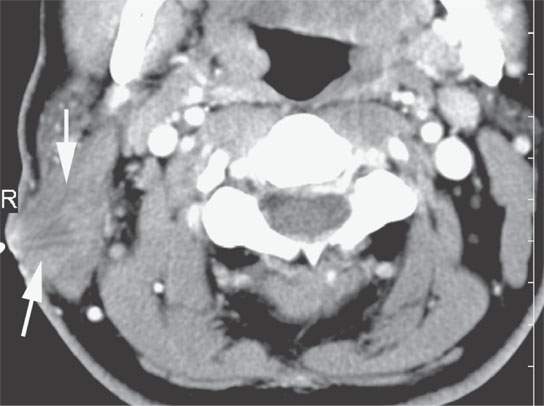

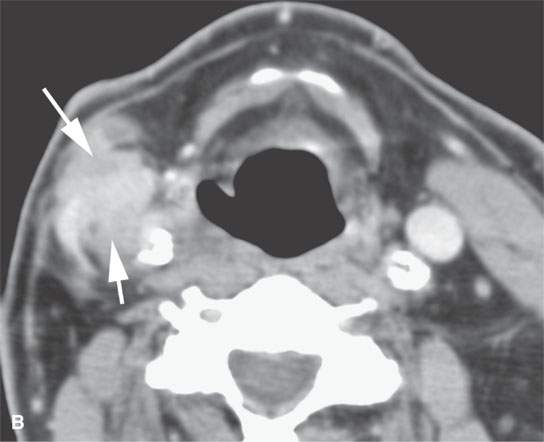

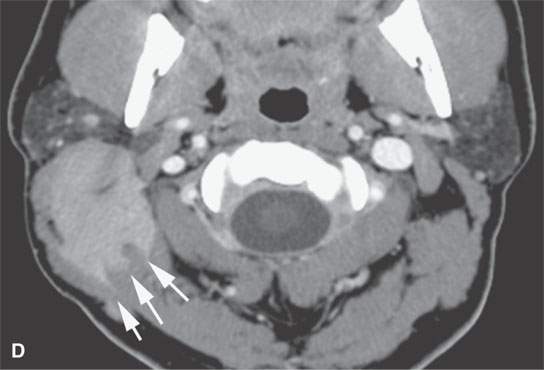

FIGURE 37.3. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of a patient with aggressive fibromatosis/desmoid tumor in the lateral compartment of the neck. A: A well-defined mass in the neck involves the carotid sheath structures. B: The highly infiltrative nature of the mass is apparent on this more inferior section from its indistinct margins and involvement of the superficial fascia and carotid artery (arrows).

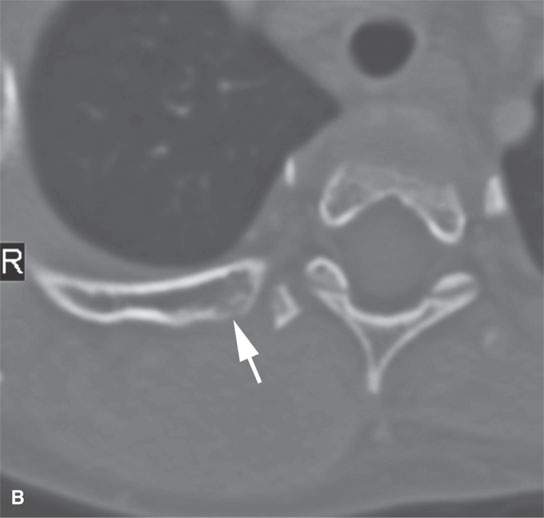

FIGURE 37.4. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography study of a pediatric patient presenting with a posterior neck mass. Differential diagnosis was between sarcoma and aggressive fibromatosis. Final diagnosis was desmoid tumor. A: The mass is relatively low density compared to skeletal muscle with only scattered areas of enhancement. In addition, there is abnormal stranding within surrounding fat plains (arrows). B: Bone windows show that the mass, while extending to the upper shoulder region posteriorly, produced some erosion of adjacent bony structures in this image of the adjacent rib (arrow).

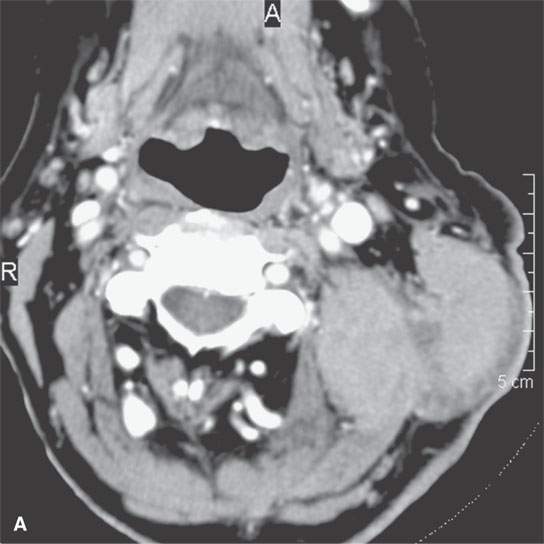

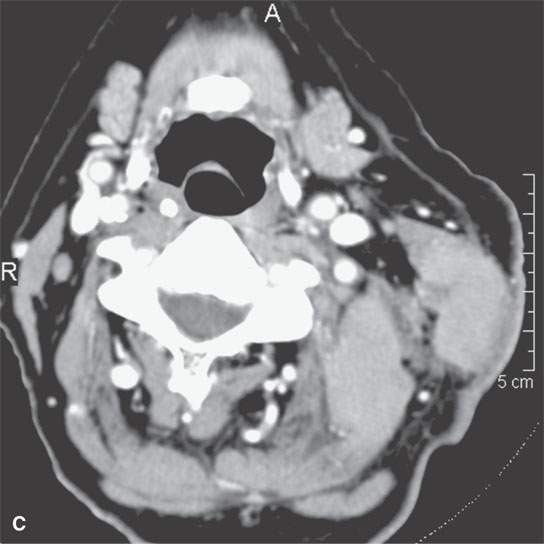

FIGURE 37.5. Two adult patients with desmoid tumors as seen on contrast-enhanced computed tomography examination. A–C: The mildly enhancing mass shows involvement of the sternocleidomastoid muscle and deeper paraspinous musculature, showing that these types of lesions easily demonstrate transcompartmental behavior. This mass spreads from the deep to the prevertebral fascia and into the sternocleidomastoid muscle, a structure that is covered by the investing (superficial) layer of deep cervical fascia. Some less enhancing zones are also present—a finding very typical of this group of fibrous origin lesions. D: Another patient showing a slightly different morphologic pattern with fairly homogeneous enhancement and no real broad zones of lesser areas of enhancement. The typical somewhat pointed or spiculated margins of the mass as it grows along fascia between various muscle bundles, both the sternocleidomastoid muscles and muscles of the posterior compartment of the neck, is a very common feature of these tumors. These margins suggest far more aggressive morphologic features than are usually present histologically. In other words, the lesions tend to look more aggressive on imaging than they are in degree of malignancy, if any.

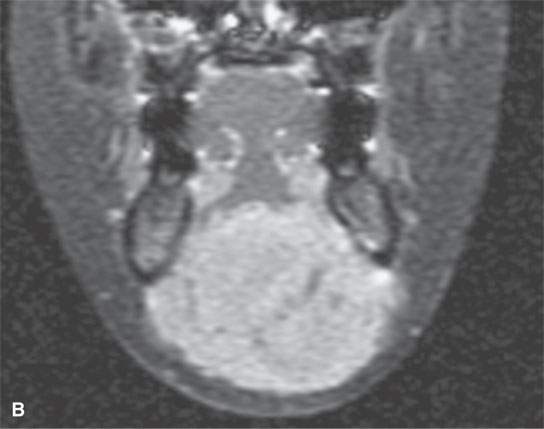

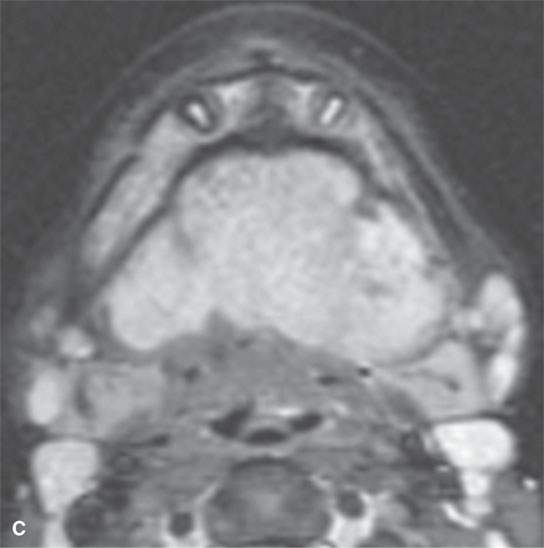

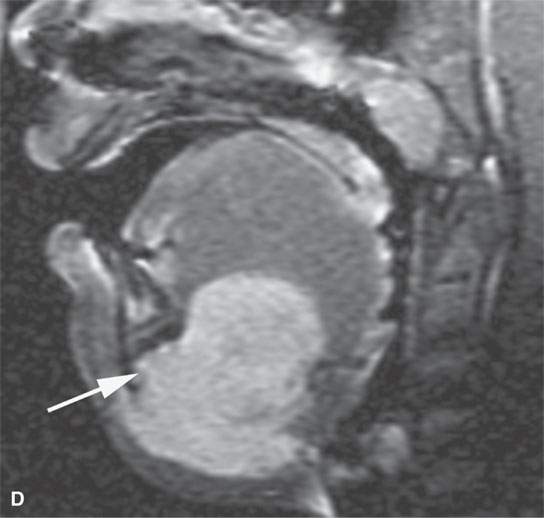

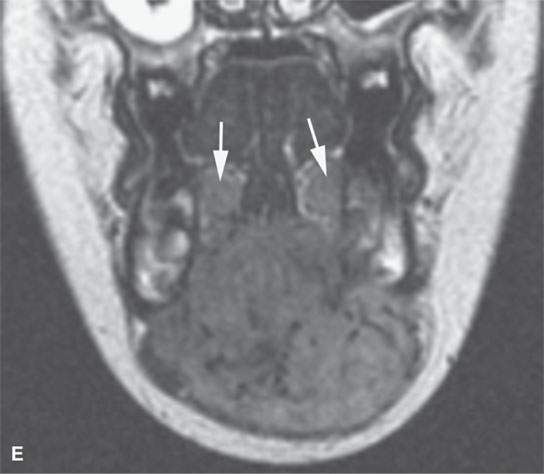

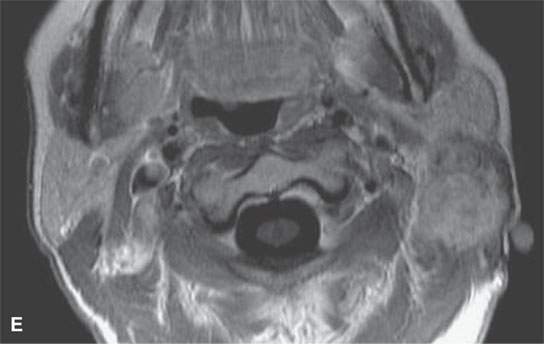

FIGURE 37.6. Magnetic resonance imaging of a pediatric patient with aggressive fibromatosis involving the floor of the mouth and suprahyoid neck. A: Non–contrast-enhanced T1-weighted (T1W) coronal image shows the mass to be equivalent to muscle in signal intensity. B: T1W fat-suppressed image following contrast injection shows the mass diffusely enhancing with little evidence of significant inhomogeneity. C: T2-weighted (T2W) axial images show the mass to be homogeneously bright compared to muscle and fat on this fat-suppressed image. D: Sagittal T1W fat-suppressed image following contrast enhancement show the mass to invade the floor of the mouth and root of the tongue and the mandible (arrow). E: T2W non–fat-suppressed image shows the mass to appear less bright as on the fat-suppressed T2W image and about isointense to the sublingual glandular tissue (arrows).

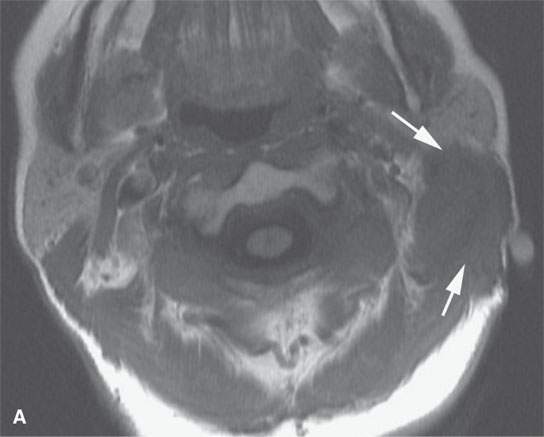

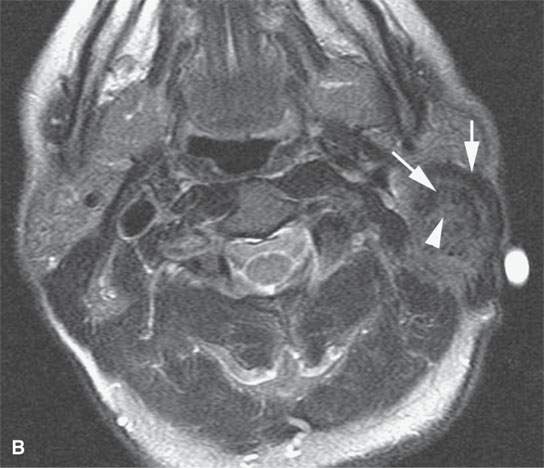

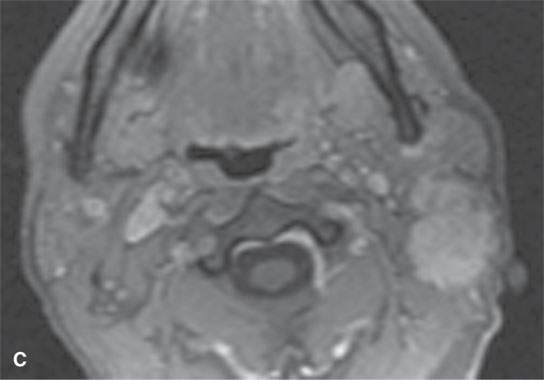

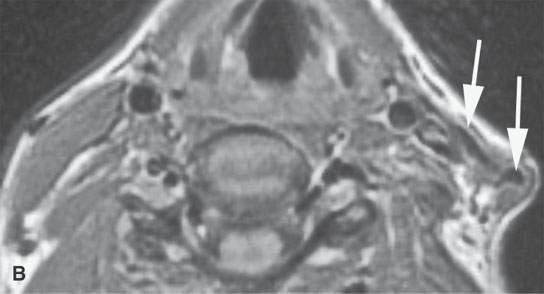

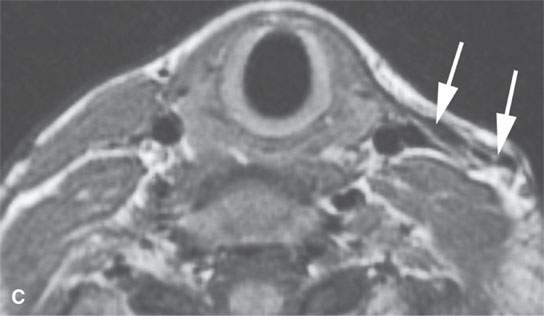

FIGURE 37.7. Magnetic resonance imaging study of an adult patient with aggressive fibromatosis of the left upper neck presenting as a neck mass. A: Non–contrast-enhanced T1-weighted (T1W) image shows the infiltrating appearing mass (arrows) to be about muscle equivalent in signal intensity. B: T2-weighted images show zones of likely dense fibrosis (arrows) admixed with zones of higher signal intensity tissue (arrowheads). C: Fat-suppressed gradient echo T1W image with contrast showing relatively homogeneous enhancement and relatively well-circumscribed margins given the histology of the lesion. Sometimes, portions these masses do not appear to be highly infiltrative at their margins. D: Fat-suppressed T1W image following contrast enhancement shows inhomogeneity of the enhancement and more aggressive margins than were appreciated on the image in (C). E: T1W spin echo non–fat-suppressed image following contrast injection for comparison with gradient echo in (C) and fat-suppressed T1W image in (D).

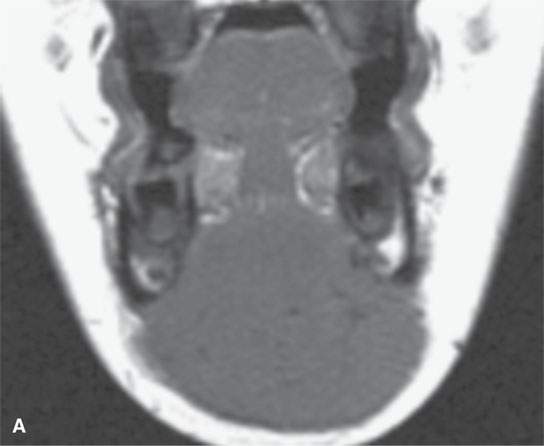

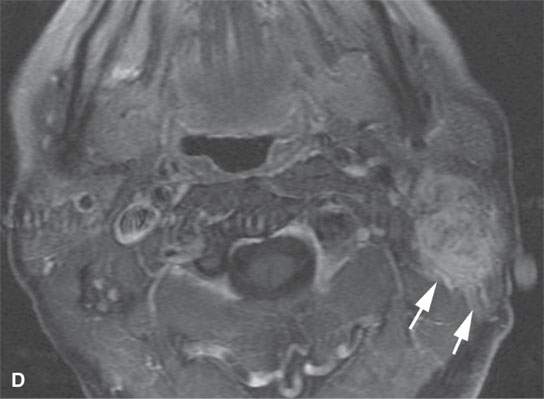

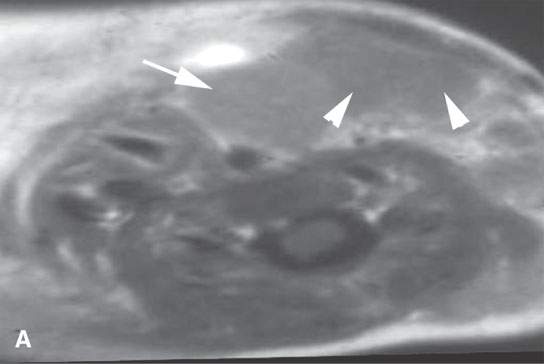

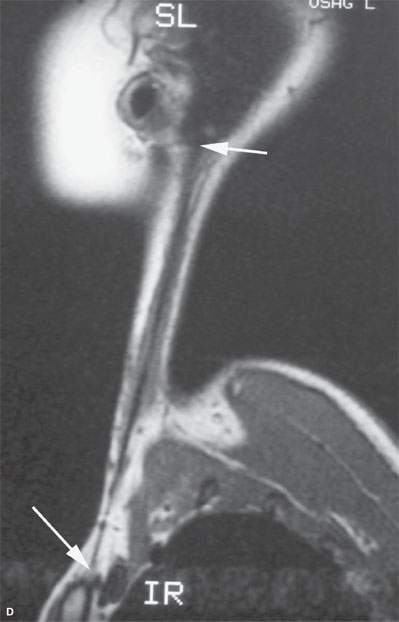

FIGURE 37.8. A: This magnetic resonance (MR) image of an infant with fibromatosis colli has a somewhat distorted aspect ratio because of the way the image was saved. However, it is illustrative of the condition showing on the contrast-enhanced T1W image the lateral neck to be occupied by a mass with differentially more (arrow) and less (arrowheads) enhancement replacing the normal sternocleidomastoid muscle. B–D: MR study in an adult showing the end-stage effects of infantile fibromatosis colli. These images all demonstrate an essentially fibrous residual strand (arrows) replacing the entire sternocleidomastoid muscle.

Juvenile and infantile fibromatosis colli of the sternocleidomastoid muscle may be difficult to differentiate from infantile spastic torticollis.1 It must be emphasized that muscular torticollis is a contraction of the sternocleidomastoid muscle without a palpable mass. In fact, biopsy of the often prominent, contracted neck muscles in both infantile torticollis and infantile fibromatosis colli has led to a mistaken diagnosis of malignancy in the past (Fig. 37.8A). Moreover, some patients with fibromatosis colli will go on to develop secondary muscular torticollis, and the fibrous bands associated with infantile torticollis pathologically may be mistaken for fibromatosis or may in fact be evidence of their sometimes linked pathophysiology (Figs. 37.8C,D).

More generalized varieties of fibromatosis also occur. The neck and supraclavicular fossa are by far the most common sites of involvement.2 Fibromatoses may involve the oral cavity and floor of the mouth, sinonasal region, and larynx.

Imaging Appearance

The masses tend to be infiltrative and ill defined, actually more so than most malignant neoplasms (Figs. 37.1–37.8). Cellular, densely collagenous, or mixed forms are possible. The cellularity occurs at the tumor’s leading edge. On T2-weighted images, there is an admixture of signal intensities with some components iso- or hypointense to skeletal muscle and others obviously brighter.3 Some modest to fairly marked enhancement might occur on both computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with intravenous contrast (Figs. 37.1–37.8). The lesions are hypointense to fat on non–contrast-enhanced T1-weighted images and about isodense or slightly less dense than muscle on non–contrast-enhanced CT.

PSEUDOSARCOMATOUS FIBROUS PROLIFERATIONS

Pseudosarcomatous proliferations may be found in the soft tissues of the head and neck. These include nodular fasciitis, proliferative myositis, proliferative fasciitis, and periosteal fasciitis (Figs. 37.9 and 37.10). All of these probably represent responses to injury. Many of these lesions are superficial and do not come to imaging. Reaction of adjacent bone may occur.

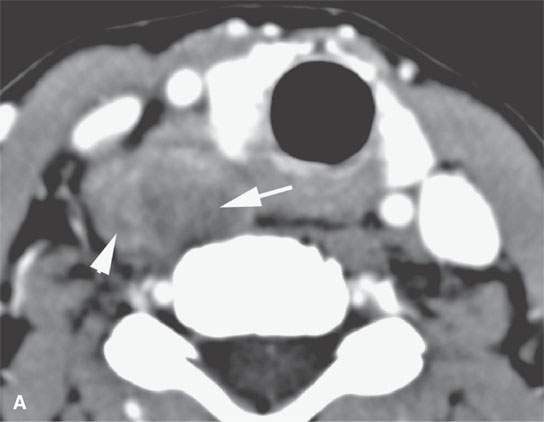

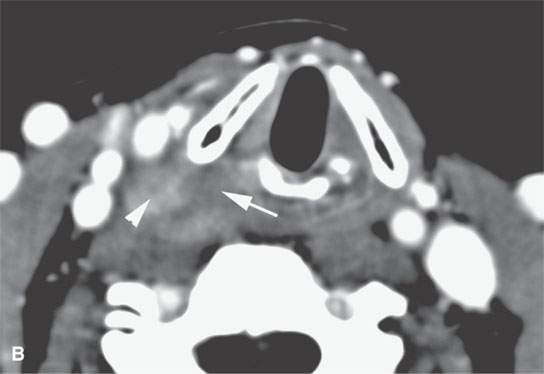

FIGURE 37.9. A patient presenting with a neck mass and dysphagia. Final pathologic diagnosis was a proliferative fasciitis.Contrast-enhanced computed tomography as seen in (A) and (B) shows a mass adjacent to the pyriform sinus apex and cervical esophagus with variable areas of enhancement (arrowheads) and nonenhancing components (arrows).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree