Benign Cystic Bone Lesions

Clyde A. Helms

A benign, bubbly, cystic lesion of the bone is one of the more common skeletal lesions a radiologist encounters. The differential diagnosis can be quite lengthy and is usually structured on how the lesion looks to the radiologist, using his or her experience as a guide. This method, called pattern identification, certainly has merits, but it can lead to a very long differential diagnosis and many erroneous conclusions if not tempered with some logic.

In general, if a differential diagnosis will yield the correct diagnosis 95% of the time, most would consider it a useful differential list; however, it would not be appropriate to accept a 1-in-20 miss rate for fractures and dislocations. In general, the shorter the differential diagnosis list, the more helpful it is to the clinicians and the easier it is to remember. A shorter differential list will usually have a lower accuracy rate than a long list; however, many times the longer lists contain such rare entities that the accuracy does not really increase substantially. For most of the entities in bone radiology, a 95% accurate differential is acceptable. If one wants to be more accurate than that, simply add more diagnoses to the list of differential possibilities.

When the differential diagnosis is long, as in the differential for bubbly, cystic lesions of bone, it can be difficult to recall all of the entities that should be mentioned. A mnemonic can be helpful in recalling long lists of information and is recommended.

Fegnomashic

FEGNOMASHIC is a mnemonic that serves as a nice starting point for discussing possibilities that appear as benign, cystic lesions in bone. This mnemonic has been in general use for many years. By itself, it is merely a long list—14 entities—and needs to be coupled with other criteria to shorten the list into manageable form for each particular case. For instance, the age of the patient will help add or eliminate many of the possibilities. If multiple lesions are present, only half a dozen entities need to be discussed. Methods of narrowing the differential are discussed later in this chapter.

The first step in approaching a benign, cystic bone lesion is to be certain it is really benign. The criteria for differentiating benign from malignant are covered in Chapter 41. Once it is established that the lesion is truly a benign, cystic lesion, FEGNOMASHIC will enable a differential diagnosis that is at least 95% accurate. Memorizing the 14 entities in this differential is easily done (Table 40.1).

The next step after learning the names of all of the lesions is getting some idea of each lesion’s radiographic appearance. This is when experience becomes a factor. For the medical student or first-year resident, it is difficult to go beyond saying that they all look cystic, bubbly, and benign. The fourth-year resident should have no trouble differentiating between a unicameral bone cyst and a giant cell tumor because he or she has seen examples of each many times before and knows their appearance.

After getting a feel for what each lesion looks like radiographically and overcoming the frustration that builds when one realizes that many of them look alike, one should try to learn ways to differentiate each lesion from the others. I have developed a number of keys that I call discriminators, which will help to differentiate each lesion. These discriminators are 90% to 95% useful (I will mention when they are more or less accurate, in my experience) and are by no means intended to be absolutes or dogma. They are guidelines but have a high accuracy rate.

Textbooks rarely state that a finding “always” or “never” occurs. They temper descriptions with “virtually always,” “invariably,” “usually,” or “characteristically.” I have tried to pick out findings that come as close to “always” as I can, realizing that I will only be approximately 95% accurate. That is good enough for most radiologists.

The following is only a brief description of each entity, as more complete descriptions are readily available in any skeletal radiology text. What is emphasized here are the points that are unique for each entity, thereby enabling differentiation from the others. Table 40.1 is a synopsis of these discriminators.

Table 40.1 Discriminators for Benign Lytic Bone Lesions—Mnemonic: Fegnomashic | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Fibrous Dysplasia

Fibrous dysplasia is a benign congenital process that can be seen in a patient of any age and can look like almost any pathologic process radiographically. It can be wild-looking, a discrete lucency, patchy, sclerotic, expansile, multiple, and many other descriptions. It is, therefore, difficult to look at a bubbly lytic lesion and unequivocally say it is or is not fibrous dysplasia. It would be better if the FEGNOMASHIC differential started on a positive note, say, with giant cell tumor or chondroblastoma, for which there are some definite criteria. Because fibrous dysplasia is first on the list, we might as well deal with it.

How do you know whether to include or exclude fibrous dysplasia if it can look like almost anything? Experience is the best guideline. In other words, look in a few texts and find as many different examples as possible; get a feeling for what fibrous dysplasia looks like.

Fibrous dysplasia will not have periostitis associated with it; therefore, if periostitis is present, one may safely exclude fibrous dysplasia. Fibrous dysplasia virtually never undergoes malignant degeneration and should not be a painful lesion unless there is a fracture. An occult fracture often occurs in long bones with fibrous dysplasia; therefore, it is not unusual to have it present with pain and no obvious fracture seen in a long bone. Pain in a flat bone, such as the ribs or skull (non–weight-bearing bones), should not occur with fibrous dysplasia.

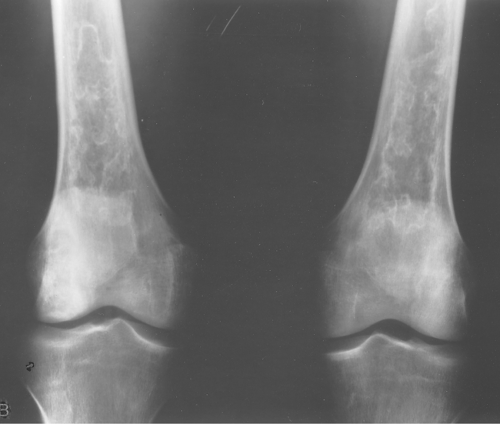

Fibrous dysplasia can be either monostotic (most commonly) or polyostotic and has a predilection for the pelvis, proximal femur, ribs, and skull. When it is present in the pelvis, it is invariably present in the ipsilateral proximal femur (Figs. 40.1, 40.2). I have seen only one case in which the pelvis was involved with fibrous dysplasia and the proximal femur was spared. The proximal femur, however, may be affected alone, without involvement in the pelvis (Fig. 40.3).

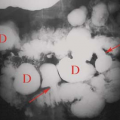

Fibrous dysplasia often involves the ribs. It typically has an expansile, lytic appearance in the posterior ribs (Fig. 40.4) and a sclerotic appearance in the anterior ribs.

The classic description of fibrous dysplasia is that it has a ground-glass or smoky matrix. This description confuses people as often as it helps them, and I do not recommend using ground-glass appearance as a buzz word for fibrous dysplasia. Fibrous dysplasia is often purely lytic and becomes hazy or takes on a ground-glass look as the matrix calcifies (Fig. 40.5). It can go on to calcify significantly, and then it presents as a sclerotic lesion. Also, I often see lytic lesions with a pathologic diagnosis other than fibrous dysplasia that have a distinct ground-glass appearance; therefore, the ground-glass quality can be misleading.

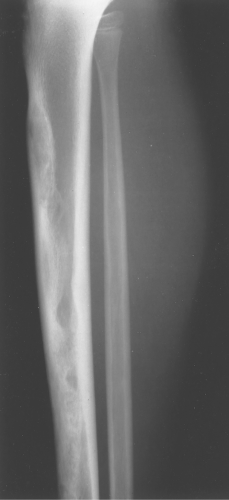

Adamantinoma. When a lesion is encountered in the tibia that resembles fibrous dysplasia, an adamantinoma should also be mentioned. An adamantinoma is a malignant tumor that radiographically and histologically resembles fibrous dysplasia (Fig. 40.6). It occurs almost exclusively in the tibia

and the jaw (for unknown reasons) and is rare. Because it is rare, one may choose not to include it in the differential—a misdiagnosis will not occur more than once or twice in a lifetime.

and the jaw (for unknown reasons) and is rare. Because it is rare, one may choose not to include it in the differential—a misdiagnosis will not occur more than once or twice in a lifetime.

Figure 40.1. Fibrous Dysplasia. This patient has polyostotic fibrous dysplasia with diffuse involvement of the pelvis as well as the proximal femurs. |

McCune Albright Syndrome. Polyostotic fibrous dysplasia occasionally occurs in association with cafe au lait spots on the skin (dark-pigmented, frecklelike lesions) and precocious puberty. This complex is called McCune–Albright syndrome. The bony lesions in this syndrome, and even in the simple polyostotic form, often occur unilaterally, that is, throughout one half of the body. This does not happen often enough to be of any diagnostic use in differentiating fibrous dysplasia from other lesions.

The presence of multiple lesions of fibrous dysplasia in the jaw has been termed cherubism. This is from the physical appearance of the child with puffed-out cheeks having an angelic look. The jaw lesions in cherubism regress in adulthood.

Discriminator. No periosteal reaction.

Enchondroma and Eosinophilic Granuloma

Enchondroma

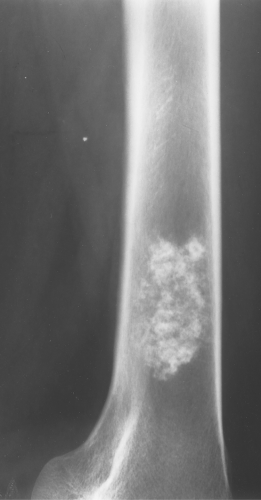

Enchondromas occur in any bone formed from cartilage and may be central, eccentric, expansile, or nonexpansile. They invariably contain calcified chondroid matrix except when in the phalanges. An enchondroma is the most common benign cystic lesion in the phalanges (Fig. 40.7). If a cystic lesion is present without calcified chondroid matrix anywhere except in the phalanges, I do not include enchondroma in my differential.

Often it is difficult to differentiate between an enchondroma and a bone infarct. An infarct usually has a well-defined, densely sclerotic, serpiginous border (Fig. 40.8), whereas an enchondroma does not (Fig. 40.9). An enchondroma often causes endosteal scalloping, whereas a bone infarct will not. Although these criteria are helpful in separating an infarct from an enchondroma, they are not foolproof.

It is difficult, if not impossible, to differentiate an enchondroma from a chondrosarcoma. Clinical findings (primarily pain) serve as a better indicator than radiographic findings, and indeed pain in an apparent enchondroma should warrant surgical investigation. Periostitis should not be seen in an enchondroma either. Trying to differentiate histologically an enchondroma from a chondrosarcoma is also difficult, if not impossible, at times (1). Biopsy of an apparent enchondroma should not be performed routinely for histologic differentiation.

Since benign enchondromas are often misdiagnosed by experienced pathologists, radiologists should not mention the possibility of a chondroid lesion being a chondrosarcoma or use phrases such as “chondrosarcoma cannot be excluded” as this will invariably lead to a biopsy, which can then result in unnecessary radical or extensive surgery. It is better to simply say “no aggressive features noted.” The surgeon is then more likely to follow it with imaging and clinical correlation.

Multiple enchondromas occur on occasion; this condition has been termed Ollier disease (Fig. 40.10). It is not hereditary and does not have an increased rate of malignant degeneration. The presence of multiple enchondromas associated with soft tissue hemangiomas is known as Maffucci syndrome (Fig. 40.11). This syndrome also is not hereditary; however, it does

have an increased incidence of malignant degeneration of the enchondromas.

have an increased incidence of malignant degeneration of the enchondromas.

Figure 40.9. Enchondroma. This lesion in the distal right femur shows the stippled punctate calcification typical of chondroid matrix seen in an enchondroma. |

Figure 40.10. Ollier Disease. Multiple enchondromas are present throughout the hand. This is a typical example of Ollier disease. |

Discriminators. (1) Must have calcification (except in phalanges), (2) No periostitis or pain.

Eosinophilic Granuloma

Eosinophilic granuloma is a form of histiocytosis X, the other forms being Letterer–Siwe disease and Hand–Schuller–Christian disease. Although these forms may be merely different phases of the same disease, most investigators categorize them separately. The bony manifestations of all three disorders are similar and are discussed in this review simply as EG.

Eosinophilic granuloma, unfortunately for radiologists, has many appearances (2). It can be lytic or sclerotic; it may be well defined or ill defined; it might or might not have a sclerotic border; and it might or might not elicit a periosteal response. The periostitis, when present, is typically benign in appearance (thick, uniform, wavy) but can be lamellated or amorphous. Eosinophilic granuloma can mimic Ewing sarcoma and present as a permeative (multiple small holes) lesion.

How, then, can one distinguish EG from any of the other lytic lesions in this differential? Remember that it is difficult to exclude EG from almost any differential of a bony lesion, be it benign or malignant. Eosinophilic granuloma occurs almost exclusively in patients less than the age of 30 years (usually <20 years); therefore, the patient’s age is the best criterion. I recommend mentioning EG as a differential possibility for any lesion in a patient less than the age of 30. Because EG can look like anything, so long as the radiograph is not of an arthritide or trauma, EG can be mentioned without even looking at the film!

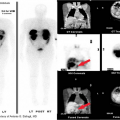

Eosinophilic granuloma is most often monostotic (Fig. 40.12), but it can be polyostotic (Fig. 40.13) and, thus, has to

be included whenever multiple lesions are present in a patient younger than the age of 30 years.

be included whenever multiple lesions are present in a patient younger than the age of 30 years.

Figure 40.12. Eosinophilic Granuloma (EG). A well-defined lytic lesion is seen involving the mid-femur in this 20-year-old patient. Biopsy showed this to be EG. |

Figure 40.14. Eosinophilic Granuloma (EG). This well-defined lytic lesion contains a bony sequestrum (arrow), which is typical of osteomyelitis or EG. Biopsy revealed this to be EG. |

Eosinophilic granuloma might or might not have a soft tissue mass associated, so the presence or absence of a soft tissue mass will not help in the differential diagnosis. I know of no entity in which the presence or absence of an associated soft tissue mass will warrant inclusion or exclusion of the process from a differential. It is important to note the presence of a soft tissue mass (or its absence), but it will do little to narrow the differential diagnosis.

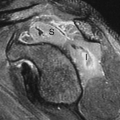

Most radiologists are inept at evaluating the soft tissues because they are difficult to see, and CT and MR have made it unnecessary in most cases to rely on plain films for the soft tissues. Fortunately, in most cases, the presence or absence of a soft tissue mass will not alter the differential diagnosis. The treating physician will undoubtedly want to know whether the soft tissues are involved and to what extent; this can be satisfactorily demonstrated with MR.

Eosinophilic granuloma occasionally has a bony sequestrum (Fig. 40.14). Only a few other entities have been described that on occasion have bony sequestra—osteomyelitis, lymphoma, and fibrosarcoma; therefore, when a sequestrum is identified, EG, osteomyelitis, lymphoma, and fibrosarcoma should be considered. As discussed in Chapter 47, an osteoid osteoma will often give an appearance of a sequestration when the nidus is partially calcified.

Clinically, EG might or might not be associated with pain; therefore, clinical history is noncontributory for the most part.

Discriminator. Must be less than age 30 years.

Giant Cell Tumor

Giant cell tumor is an uncommon tumor found almost exclusively in adults in the ends of long bones and in flat bones (3).

It is important to realize that one is unable to tell whether a giant cell tumor is benign or malignant, regardless of its radiographic appearance. Histologically, a giant cell tumor cannot be divided into either a benign or a malignant category. Most surgeons curettage and pack the lesions and consider them benign unless they recur. Even then, they can still be benign and recur a second or third time. About 15% of giant cell tumors are thought to be malignant on the basis of their recurrence rate. When malignant, they can metastasize to the lungs, but they do so rarely.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree