BENIGN LYMPHOID AND OTHER REACTIVE AND PROLIFERATIVE PROCESSES INCLUDING POSTTRANSPLANT LYMPHOPROLIFERATIVE DISORDER

KEY POINTS

- Proliferation of lymphoid tissue is most often a self-limited reactive event that occurs in a clinically obvious benign clinical context.

- Proliferation of lymphoid tissue may mimic malignancy or infectious or noninfectious inflammatory disease when it shows aggressive behavior on imaging studies.

- Imaging findings are often nonspecific in these disorders but in the proper clinical perspective may help confirm clinical suspicions and sometimes offer clues to a specific diagnosis.

THE IMAGING DILEMMA

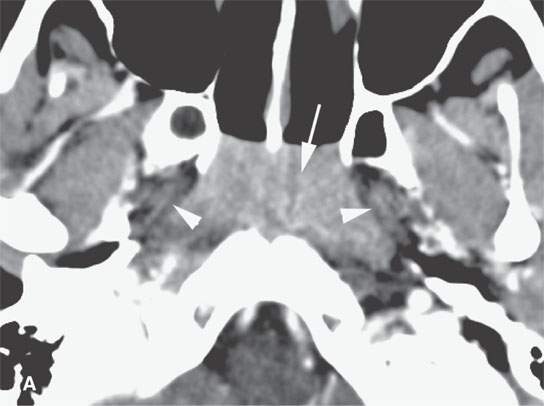

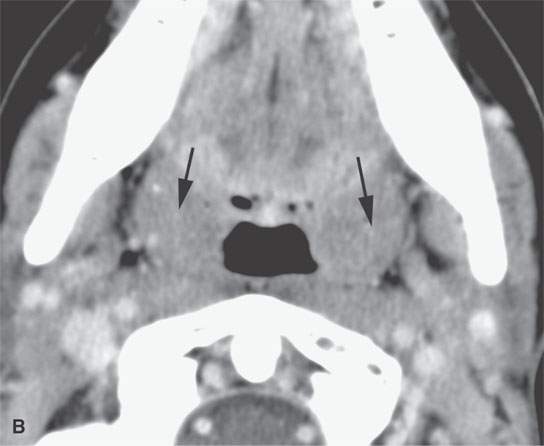

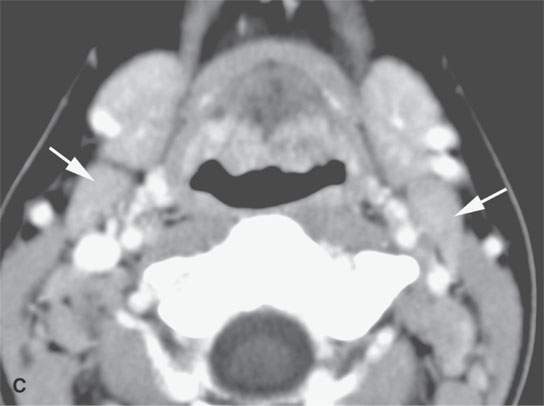

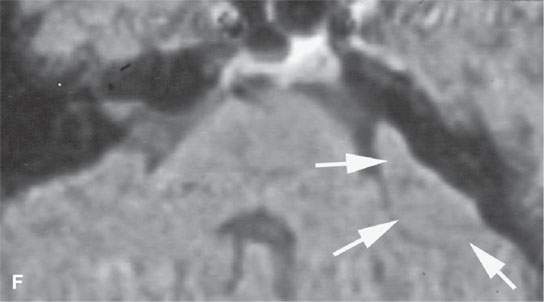

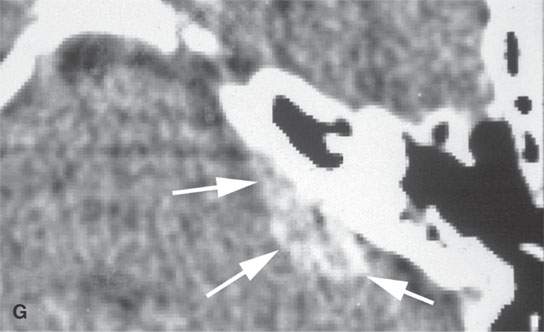

It is difficult to differentiate benign reactive lymphoid proliferations from lymphoma on computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance (MR), and ultrasound examinations unless there is invasion of deep tissue planes or some alteration in lymph node architecture such as necrosis or capsular penetration, vascular flow patterns suggesting aggressive pathology.1,2 Even with such “aggressive behavior,” the proliferation may not be malignant (Figs. 26.1–26.3). Neither MR signal changes, generalized CT density alterations, nor patterns of contrast enhancement within the lymphoid tissue add unequivocal specificity.3 This includes patterns that may be observed on contrast-enhanced dynamic flow and perfusion studies. Contrast enhancement only makes it easier to evaluate important gross morphologic features that result in focal nodal defects or invasive character of the extranodal lymphoid proliferation. Ultrasound flow patterns, resistive indices, and diffuse architectural nodal changes are generally nonspecific in specifying particular infiltrating nodal pathologies4; however, ultrasound can typically separate infiltration such as that due to lymphoma from reactive proliferative changes (Fig. 26.4). Infiltration of tissue planes deep to the nasopharyngeal, palatine, or lingual tonsils may suggest lymphoma, prompting biopsy5; however, this may be due to HIV infection and enlarged inflamed adenoids due to Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) or other viral infections as well as bacterial and fungal adenoiditis (Figs. 26.2 and 26.5).

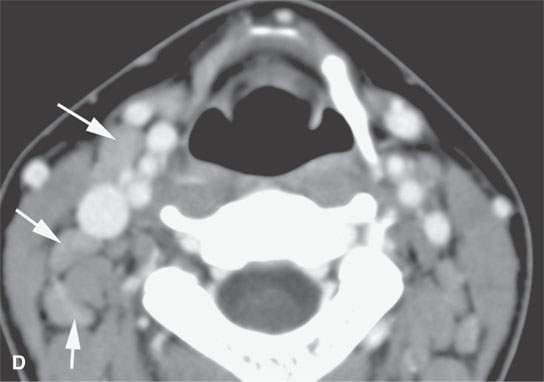

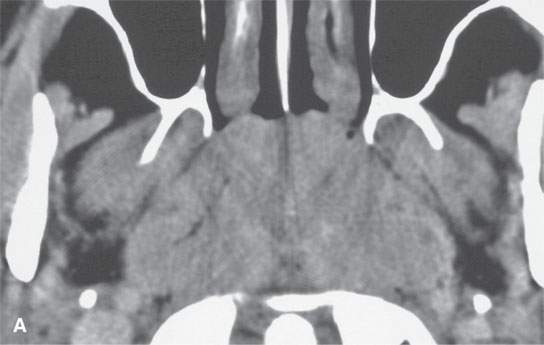

FIGURE 26.1. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of a young adult with primary Epstein-Barr virus infection. A: The adenoidal tissue in the nasopharynx is hypertrophic and enhances more than normal (arrow), but it is not invading the parapharyngeal fat (arrowheads). B: The palatine tonsils are hypertrophic (arrows), but this is nonspecific. C: There are slightly enlarged, enhancing level 2B reactive nodes present bilaterally (arrows). D: The adenopathy is even more abnormal in level 3 and 5A nodes, especially on the right (arrows).

FIGURE 26.2. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of a patient with lymphoid hypertrophy of the adenoidal tissue due to HIV infection.

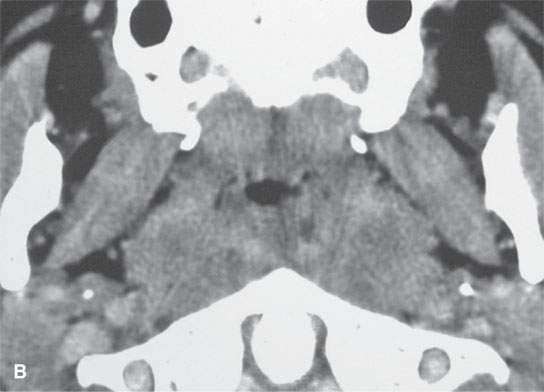

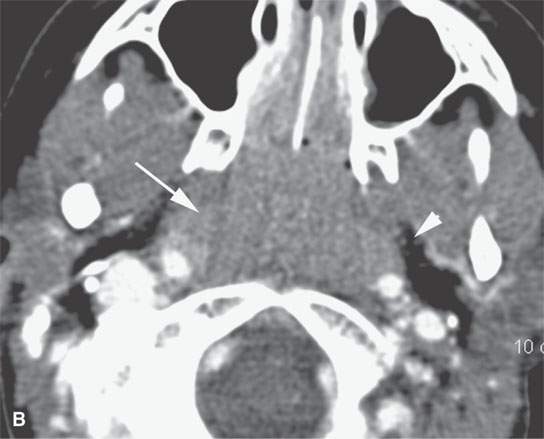

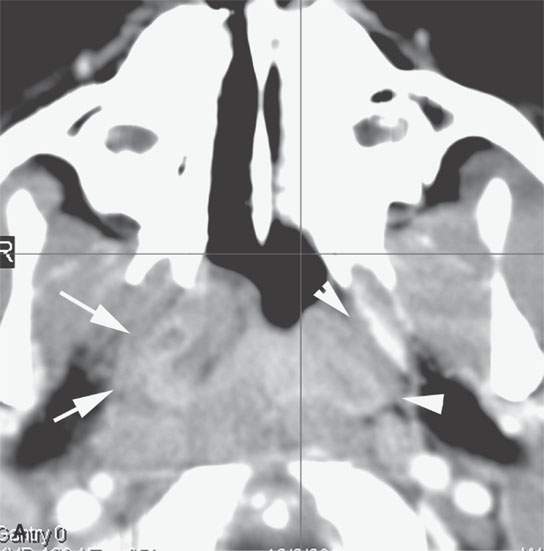

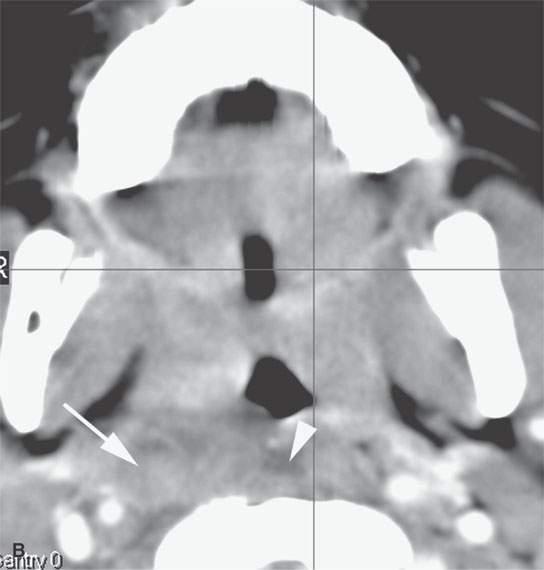

FIGURE 26.3. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of a transplant patient with posttransplant lymphoproliferative disordermanifesting in the adenoidal pad by hypertrophy of the lymphoid tissue but more important infiltration of the parapharyngeal fat on the right (arrows) compared to the left (arrowhead).

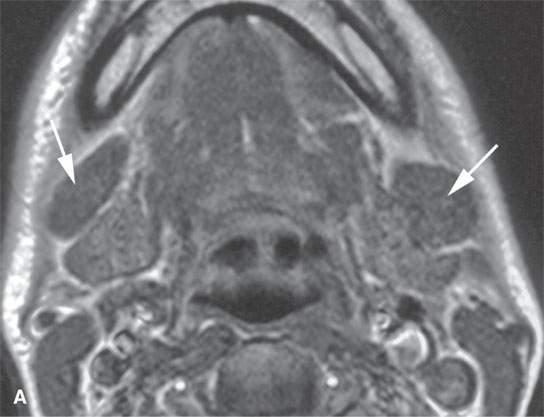

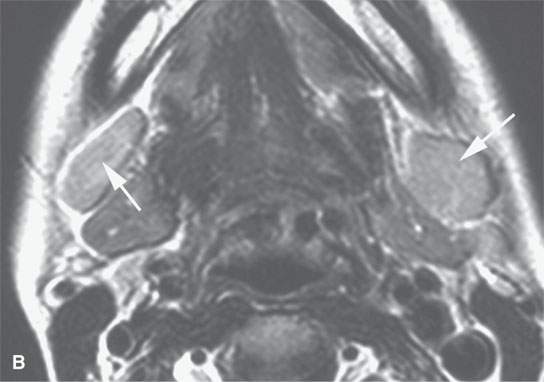

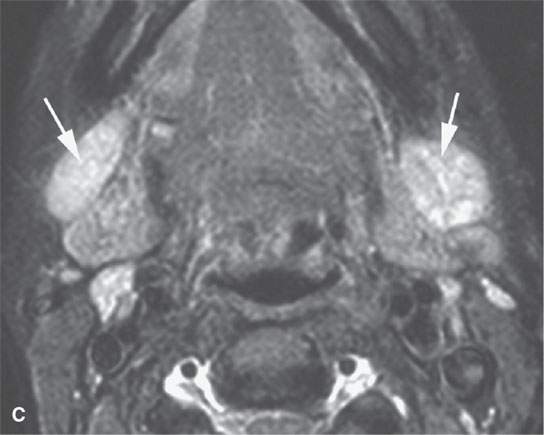

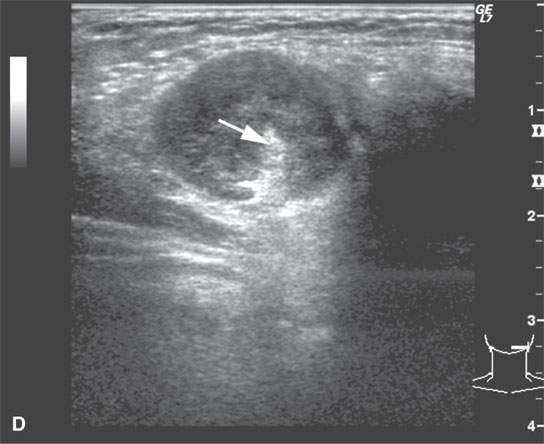

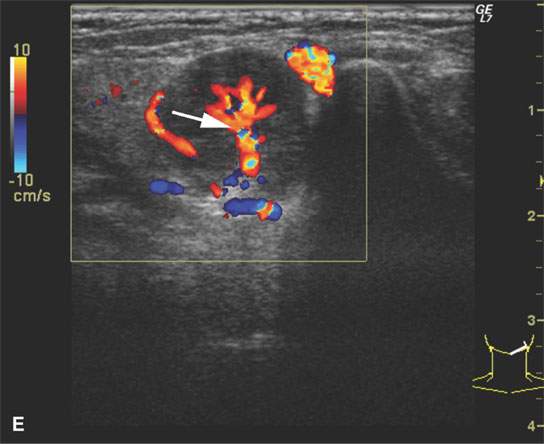

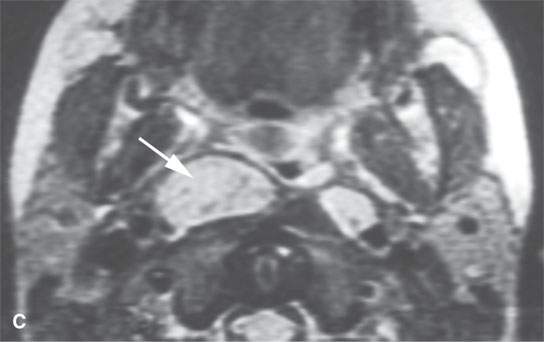

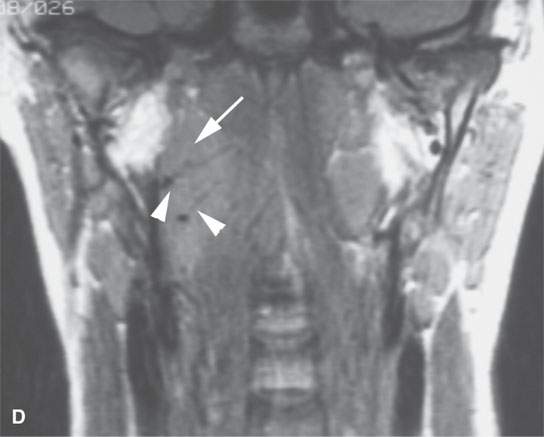

FIGURE 26.4. Magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound (US) of a patient with enlarged reactive nodes (arrows) due to Epstein-Barr virus infection, with the node remaining homogenous on images and somewhat hypervascular. A: Non–contrast-enhanced T1-weighted (T1W) image. B: Contrast-enhanced T1W image. C: T2-weighted image. D: US image suggesting prominent hilar structures (arrow). E: Color flow US image showing a large vascular pedicle in the node hilum (arrow) and mainly central hypervascularity.

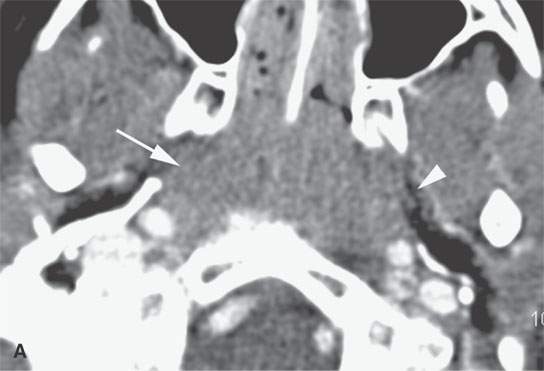

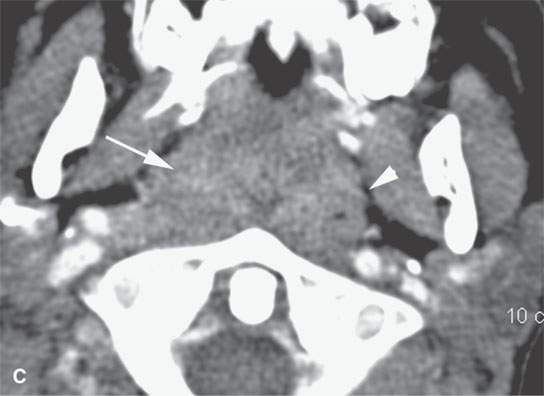

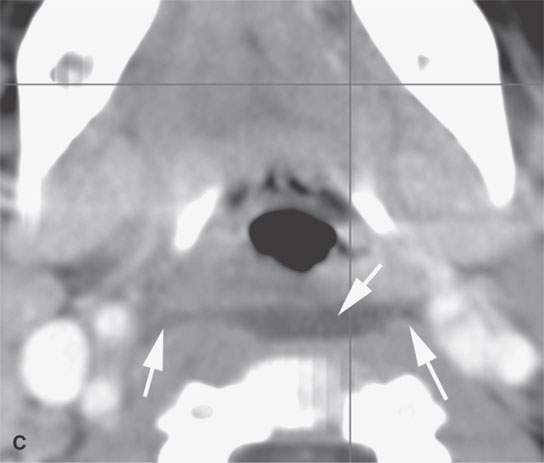

FIGURE 26.5. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of a patient with acute streptococcal pharyngitis manifesting by the following:in the adenoidal pad by hypertrophy of the lymphoid tissue but more importantly infiltration of the parapharyngeal fat on the right (arrows) compared to the left (arrowhead) (A), early suppurative retropharyngeal lymph adenopathy (arrow) and early retropharyngeal edema (arrowhead) (B), and more obvious retropharyngeal edema (arrows) (C).

ROUTINE AND MORE WORRISOME PATTERNS OF REACTIVE HYPERPLASIA

Both the lymphoid tissue in the Waldeyer ring and the cervical nodes may respond to a variety of immunologic challenges and become hyperplastic.6 Typically, this stimulus is something as simple as a viral or bacterial upper respiratory illness that can be expected to run its course in about 14 to 21 days and the related changes resolve. In some cases, such as EBV infection, the antigenic response seems to be prolonged and clinically raises the concern over lymphoma or some other less typical lymphoproliferative, but not neoplastic, reactive process7,8 (Figs. 26.1 and 26.5).7,8

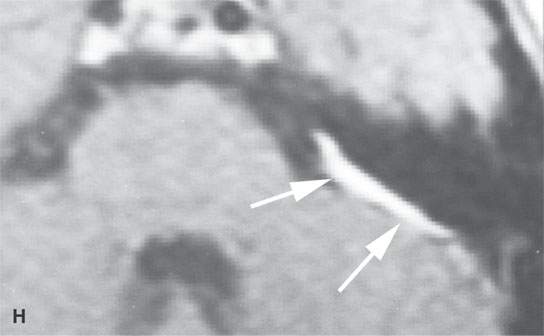

Yet undiscovered antigenic stimuli seem capable of producing massive, although histologically benign, patterns of lymph node and extranodal lymphoid proliferations, but the imaging picture remains somewhat nonspecific with regard to whether the proliferation is benign or malignant.9 The most common of these uncommon conditions are angiofollicular lymph node hyperplasia, also known as Castleman disease (Fig. 26.6); sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy, also known as Rosai-Dorfman disease (Fig. 26.7); Kimura disease (Fig. 26.8) and angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia; immunoblastic lymphadenopathy; and angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy with dysproteinemia. Kimura disease is the one with the most potential for extranodal disease (Fig. 26.8), but this can be seen in Rosai-Dorfman (Fig. 26.7) and Castleman disease as well10(Fig. 26.6F–H).10 There are other similar although more uncommon histologic diagnoses possible in this category of diseases. Issues related to lymph node morphology in benign and malignant lymphoproliferative diseases is discussed more detail in conjunction with primary lymphadenopathies in Chapters 157 and 158 and in conjunction with the general topic of lymphoma in Chapter 27.

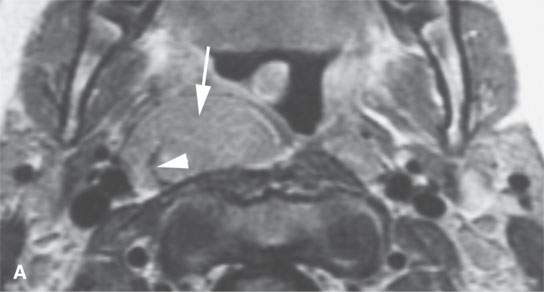

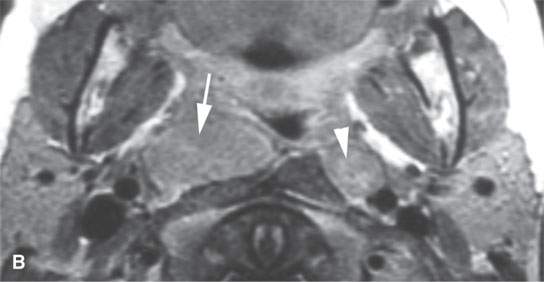

FIGURE 26.6. Two patients with Castleman disease. Magnetic resonance (MR) images in the first patient show a very large enhancing retropharyngeal lymph node (arrows) on the right with a prominent vascular pedicle (arrowheads in A, D, and E) on contrast-enhanced T1-weighted images (A–C,B,D, E) with the node being bright on the T2-weighted image (CD).Contrast-enhanced MR and computed tomography images of the second patient before biopsy and treatment showed a sessile dural-based cerebellopontine angle mass (arrows in F and G). The lesion waxed and waned with steroid administration (arrows in gHG) and finally resolved. Biopsy confirmed Castleman disease.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree