Imaging of Benign Ovarian Lesions

Sonography, especially transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS), has become the primary imaging technique for the evaluation of the ovary. Because the majority of ovarian lesions are benign, it is important for those interpreting images to be able to recognize those features that are characteristic of commonly encountered physiologic ovarian cystic lesions and benign ovarian neoplasms to guide patient management.

Sonography is a readily available and cost-effective imaging technique that provides high resolution of the ovary, allowing the best evaluation of the internal composition of cystic ovarian lesions. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is often used to investigate indeterminate sonographic findings, adding specificity for the diagnosis of complex cystic ovarian lesions such as endometriomas and dermoid cysts, as well as solid, benign fibrous ovarian neoplasms.

Ovarian Follicles

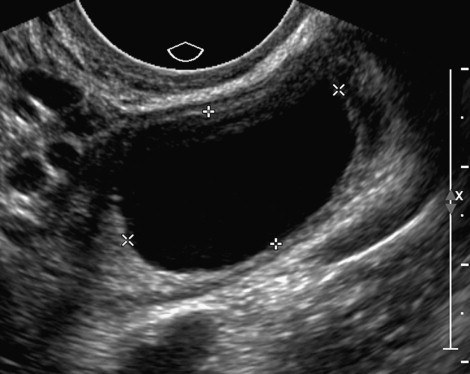

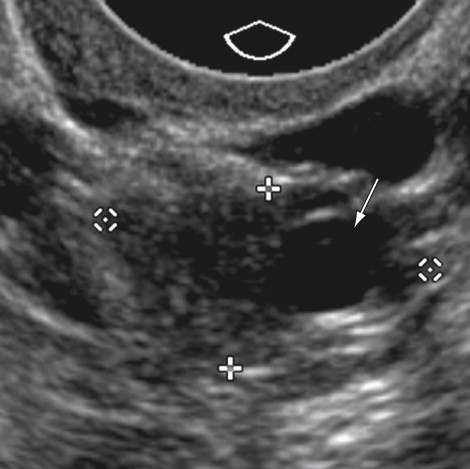

The most common cystic ovarian lesions detected in premenopausal patients are often physiologic in nature, representing a developing follicle, a follicular cyst, or a corpus luteum. The ovary contains millions of microscopic primordial or immature follicles, several of which will enlarge on a continual basis in the hormonally active ovary. In response to follicle-stimulating hormone, a group of these follicles will become visible by high resolution imaging. Developing or immature follicles typically appear as sharply marginated, fluid-filled, unilocular cysts measuring between 2 and 9 mm in maximal dimension. It is these follicles that allow identification of the ovarian parenchyma on imaging techniques ( Figure 29-1 ). In the first half of each menstrual cycle, one or more dominant follicles will grow to a diameter of approximately 20 to 25 mm and then rupture at ovulation, releasing the oocyte. Some authors believe it is best to refer to these small, simple-appearing cystic lesions as follicles rather than cysts to emphasize that they are a normal physiologic finding. The preovulatory dominant follicle may have a slightly complicated appearance, with the oocyte and its supporting structures (the cumulus oophorus) appearing as a curvilinear septation with the follicle ( Figure 29-2 ). In a small number of women, a mature follicle will fail to ovulate and continue to enlarge into the next menstrual cycle, sometimes attaining a size greater than 5 cm. The appearance of these follicular cysts is a unilocular cyst with thin walls, sharply defined borders, and anechoic internal fluid ( Figure 29-3 ). These lesions are most commonly discovered incidentally in asymptomatic women with a clinical history of menstrual irregularity. Although the presence of a large cystic ovarian lesion may raise concern for a neoplasm, repeating an ultrasound (US) examination after one or two menstrual cycles is recommended because many lesions will undergo involution, allowing diagnosis of a follicular cyst.

Postmenopausal Cysts

Although the postmenopausal pelvis was thought to be hormonally quiescent, simple ovarian cysts are detected in 3% to 15% of all postmenopausal women undergoing transvaginal sonography. The majority are small, less than 3 cm, and tend to resolve spontaneously or remain stable in size over serial examinations. These resolving cystic lesions are most likely serous inclusion cysts, which occur in women of all ages and arise as a result of cortical invagination of the surface epithelium into the ovarian parenchyma. On imaging, these inclusion cysts should be less than 3 cm, thin-walled, unilocular, anechoic, and devoid of vascularity ( Figure 29-4 ). In those patients with persistent simple-appearing cysts, the most common pathology is a benign serous cystadenoma. Although initial reports found a malignancy rate of more than 10% in postmenopausal simple-appearing cysts, several more recent large series using TVUS have found the risk of malignancy to be 1% or lower, particularly for lesions smaller than 5 cm. Therefore some clinicians will elect to follow 3-cm or smaller simple-appearing, ovarian cystic lesions in low-risk postmenopausal patients who have normal cancer antigen (CA)-125 levels with serial annual or biannual TVUS examinations and CA-125 levels. If the lesion resolves or is stable in size for 2 years, it is considered benign. If the CA-125 increases or if the lesion enlarges or becomes complicated by septations or the presence or vascular flow, surgical removal is recommended to exclude an ovarian malignancy. The opinion of a recent consensus conference sponsored by the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound (SRU) recommends that in asymptomatic postmenopausal women, simple cysts less than 1 cm can be ignored, simple cysts between 1 and 7 cm are usually benign but should be followed yearly with US, and when lesions are larger than 7 cm, consideration should be given for additional imaging with MRI or surgical removal.

Corpus Luteum

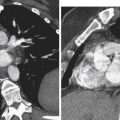

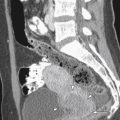

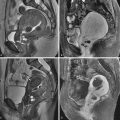

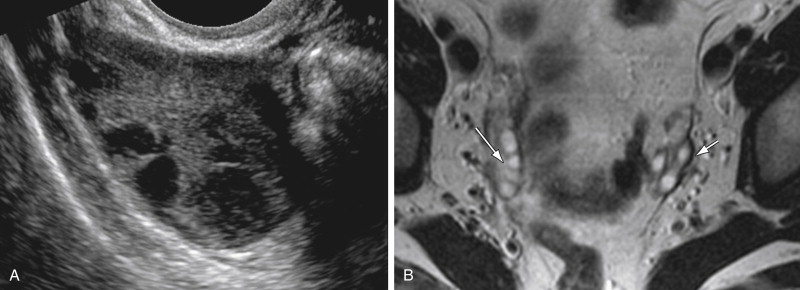

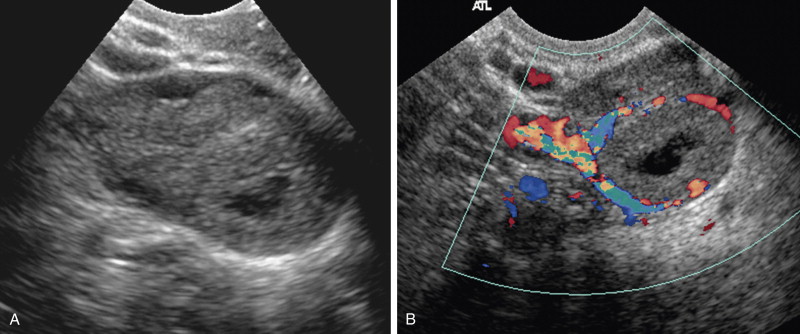

The corpus luteum evolves from the remnant of the mature follicle after ovulation through a process of cellular hypertrophy of the follicle’s granulosa and theca cells and increased vascularization of the cyst wall. Therefore the corpus luteum is noted in the secretory phase of the menstrual cycle and in the first few weeks of early pregnancy. Typically the corpus luteum is less than 3.0 cm in maximal dimension, reflecting its origin as a follicle but may be as large as 6 to 10 cm. A corpus luteum is typically unilocular but will have a thick and irregular or partially collapsed wall and often contains complex fluid reflecting blood products and lymph that filled the follicle at the time of rupture. On sonography the center of the corpus luteum may appear simple just after ovulation but tends to become more echogenic as the cyst cavity becomes filled by debris and hemorrhagic. The wall is typically fairly echogenic, often with irregular and poorly defined margins, and on color Doppler sonography is highly vascular, but no flow is seen centrally ( Figure 29-5 ). On MRI the wall of the corpus luteum may exhibit slightly increased intensity on T1-weighted images and low intensity on T2-weighted images, likely reflecting blood products. The wall may show avid enhancement on MRI and computed tomography (CT), reflecting the increased vascularity of the thick luteinized cell layer, but is usually less than 3 mm in thickness ( Figure 29-6 ). The corpus luteum may rupture, producing free fluid adjacent to the ovary and dependently within the cul-de-sac region of the pelvis ( Figure 29-7 ).

Hyperstimulated Ovaries

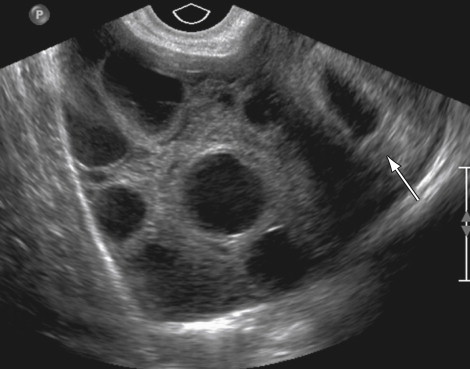

Increased human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) serum levels or increased sensitivity to normal levels can cause marked enlargement of the ovaries and production of multiple theca lutein cysts. When the elevated hCG is associated with ovulation induction, the condition is called ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS). If associated with a normal pregnancy, multiple gestations, or gestational trophoblastic disease, the condition is termed hyperreactio luteinalis (HL). OHSS tends to present in the first trimester and is associated with ascites and pleural effusions. HL tends to have a more indolent course and presents later in pregnancy. In both conditions, the ovaries are markedly enlarged with multiple simple-appearing or minimally complicated cysts that often contain hemorrhage. On sonography the central ovarian stroma extends from the central aspect of the ovary peripherally and is stretched by the multiple cysts, producing a characteristic “wheel spoke” appearance ( Figure 29-8 ).

Hemorrhagic Cysts

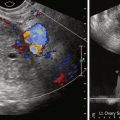

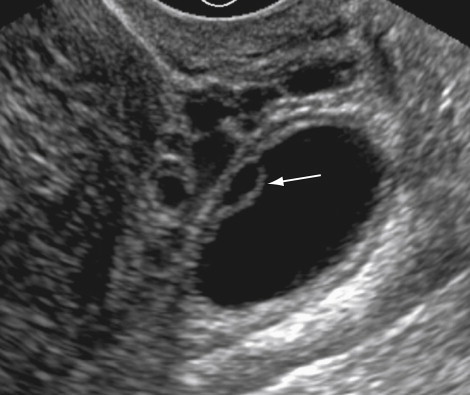

Hemorrhagic cysts occur as a result of bleeding into a follicular cyst or a corpus luteum and can happen at any time during the menstrual cycle. The most common clinical presentation is the abrupt onset of acute pelvic pain; less commonly the patient is asymptomatic. Variable characteristics can be seen in these hemorrhagic cysts, depending on the stage of clot formation, lysis, and retraction. On sonography, hemorrhagic cysts often contain interdigitating strands of fibrin, a characteristic appearance referred to as fish weave or reticular pattern . These strands differ from true septations, which are commonly present in cystic ovarian neoplasms, by their thin size (<1 mm), their lack of vascularity, and their poor reflectivity of sound, making them only faintly visible ( Figure 29-9 ). Retracting clot within a hemorrhagic cyst should not be mistaken for a solid component of a cystic neoplasm. Retracting clot will often have concave or straight margins at its fluid interface and is typically less echogenic than the cyst wall on TVUS (see Figure 29-9 ). The soft tissue mural nodules detected in an ovarian neoplasm are of equal or slightly greater echogenicity than the wall and have convex margins at the fluid interface. Additionally, retracting clot will fail to show vascular flow on Doppler examination or enhancement by CT or MRI. On CT a hemorrhagic cyst appears as a unilocular cyst with an internal attenuation of 25 to 100 Hounsfield units. Fluid–fluid levels and hemoperitoneum may be noted after rupture. Rarely rupture may occur with significant hemoperitoneum necessitating surgical intervention. On MRI an ovarian cyst complicated by acute hemorrhage will have high signal on a T1-weighted image, similar to an endometrioma. Because hemorrhagic cysts will resolve spontaneously, short-interval follow-up sonography can be recommended if hemorrhagic cyst is considered as a possible diagnosis for a complex adnexal lesion in a premenopausal patient.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree