Abstract

The fetal biliary tract can give rise to congenital abnormalities, including biliary atresia, choledochal cysts, and gallstones. They are amenable to prenatal diagnosis but can be challenging to recognize. Billiary atresia is suspected on prenatal ultrasound when the gallbladder is absent. Choledochal cysts usually appear as an intrahepatic, fluid-filled mass.

Keywords

biliary atresia, choledochal cyst, fetal gallstones, kasai portoenterostomy

Introduction

The diagnosis and detection of some forms of bile duct disease have become possible with routine prenatal ultrasound. However, it remains difficult to offer a specific diagnosis or even prognosis in most cases. The most common finding is probably cystic dilatation of the biliary tree, mainly because of choledochal cysts or biliary atresia. In this chapter, biliary atresia, choledochal cysts, and gallstones will be discussed, as they are amenable to prenatal diagnosis.

The gallbladder and the cystic duct begin to form during the fourth week of embryonic development as a cystic diverticulum situated below the hepatic diverticulum at the level of the duodenum. As soon as development of the cystic diverticulum is completed, cell proliferation at the junction of the cystic and hepatic ducts lead to formation of the intra- and extrahepatic biliary tracts. Bile excretion starts around the 12th week of gestation. At around the same time, the gallbladder and the cystic duct are completely formed and the cystic duct joins the common hepatic duct to form the biliary duct. The biliary tract is patent allowing bile secretion into the intestinal tract.

The fetal gallbladder can be visualized from the 14th–16th week onward and it is seen in 65% to 82% of fetuses at 24–27 weeks’ gestation. Its size increases continuously until 30–34 weeks’ gestation and then remains unchanged until term.

On ultrasound, the gallbladder appears as a small, hypoechoic, oval cystic structure located at the lower border of the liver, close to the intestinal loops, and to the right of the intraabdominal umbilical vein. It is smaller than the stomach. Its shape and volume can vary from one fetus to another.

Biliary Atresia

Definition

Biliary atresia (BA) is the destructive inflammatory obliterative cholangiopathy of neonates. BA is not associated with calculi, neoplasm, or rupture.

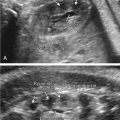

It is a life-threatening condition in infants, one of the most common causes of neonatal cholestasis and the most frequent indication for liver transplantation in childhood. If untreated, progressive liver cirrhosis leads to death by the age of 2 years. Early diagnosis and intervention are important for a better outcome. The disease is classified based on the anatomic pattern of the extrahepatic biliary tract remnant ( Fig. 25.1 and Table 25.1 ).

| French Classification | Frequency (%) | Description | Upper Level of Obstruction of the Extrahepatic Bile Ducts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type 1 | 3 | Atresia limited to the common bile duct | Common bile duct |

| Type 2 | 6 | Cyst in the liver hilum communicating with dystrophic intrahepatic bile ducts | Hepatic duct |

| Type 3 | 19 | Gallbladder, cystic duct, and common bile duct patent | Porta hepatis |

| Type 4 | 72 | Complete extrahepatic biliary atresia | Porta hepatis |

Prevalence and Epidemiology

Biliary atresia (BA) is a rare disorder with estimates of national prevalence ranging from 0.2 : 10,000 to 0.5 : 10,000 in the UK and France. It is more common in East Asia and has a prevalence of 2 : 10,000 in Taiwan. There is no sex predilection in Caucasians, although in Japan there is a female predominance. BA is rarely familial and in twins is usually discordant.

Associated congenital anatomic abnormalities are found in up to 20% of neonates, the most common being biliary atresia-splenic malformation syndrome (BASM syndrome), reported in about 10% of a European series. Clinical features of the laterality defect sequence, such as asplenia, polysplenia, and situs inversus, can be present. Cardiac, gastrointestinal, renal, and urinary tract anomalies have also been described ( Table 25.2 ). BA has also been seen in trisomies 18 and 21.

| Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|

| Splenic malformation (e.g., polysplenia, asplenia, double spleen) | 100 |

| Situs inversus | 37 |

| Intestinal malrotation | 60 |

| Absent inferior vena cava | 70 |

| Cardiac anomalies (e.g., ventricular or atrial septal defect, hypoplastic left heart) | 45 |

| Pancreatic anomalies (e.g., annular pancreas) | 11 |

In 80% to 90% the disorder seems to be isolated. It is thought that the obliterative process begins in the perinatal period in this group of patients (“perinatal” or “acquired form”), whereas it is believed to begin in the embryonic phase in the syndromic cases (“congenital” or “embryonic form”). In some cases of isolated BA, cystic changes are observed within the obliterated biliary tree (cystic biliary atresia) and can also be detected on prenatal ultrasound examination.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

The cause of BA remains unknown, and the disease is believed to be multifactorial in nature. Some cases seem to be related to abnormal morphogenesis of the bile ducts early in gestation, whereas others seem to result from later damage to normally developing bile ducts. Genetic, vascular, inflammatory, and toxic insults might contribute to the obliterative cholangiopathy observed in BA.

Manifestations of Disease

Clinical Presentation

BA typically presents shortly after birth with persistent jaundice, pale stools, and dark urine in term infants with normal birth weights. Initially the child is in good condition. Weight loss, irritability, and increasing levels of jaundice develop later. Splenomegaly, ascites, and hemorrhage (impaired absorption of vitamin K) develop. Untreated, this condition leads to cirrhosis and death within the first years of life.

Imaging Technique and Findings

Ultrasound.

The prenatal diagnosis of BA is difficult and remains exceptional (about 5%). On prenatal ultrasound, it is suspected when the fetal gallbladder cannot be seen on any occasion, which is sometimes associated with a small cystic structure in the liver hilum. ( Fig. 25.2 ).

Mainly BA types 1 and 2, which occur less frequently, can be suspected on prenatal sonography. In such cases amniocentesis is recommended for cystic fibrosis screening, hepatic enzyme tests, and karyotyping. Digestive enzymes are present in the amniotic fluid (AF) from the 12th week onward and will increase until the 18th week, after which maturation of the anal sphincter progressively impairs this. After 22 weeks, there are normally only very low levels of digestive enzyme activities in AF, making it difficult to discern between physiologically and abnormally low levels. Therefore, it is only useful to measure digestive enzymes in the amniotic fluid before the 22nd week. Biliary atresia is associated with a very low level of only the hepatic enzyme gamma-glutamyl-transpeptidase (GGTP), which is secreted from the biliary epithelium, while in cystic fibroses there is a very low level of all digestive enzymes including alkaline phosphatase (AP), which is secreted by the enterocytes. High level of GGTP at 22 weeks is considered as a reassuring sign.

After birth, the clinical triad of BA is jaundice, acholic stools, and dark urine, as well as hepatomegaly.

Choledochal Cysts

Definition

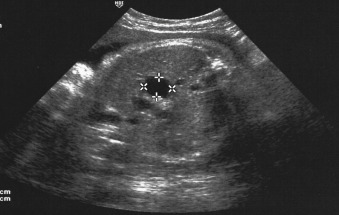

Choledochal cysts (CC) are rare congenital anomalies of the biliary tract that are the result of an abnormally long common pancreaticobiliary duct allowing reflux of pancreatic enzymes into the biliary ducts. It is four times more common in girls and considered a disease of infancy, with 40% to 60% of cases being diagnosed before the age of 10. The Todani classification is descriptive and distinguishes five types of CC ( Fig. 25.3 and Table 25.3 ). Type I is the most common type with a saclike dilatation of the common bile duct. Type V, also known as the autosomal recessive Caroli disease , shows cystic dilatations of the intrahepatic biliary duct.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree