BONE AND OTHER METASTATIC DISEASE TO THE HEAD AND NECK

KEY POINTS

- Metastatic disease can sometimes mimic localized head and neck origin pathology.

- The head and neck may be the presenting site of metastatic disease.

- The pattern of imaging findings is critical to anticipating that metastatic disease may be a very likely diagnostic option.

- Systemic types of screening studies are sometimes warranted in the workup of a head and neck lesion suspected of being a metastasis, especially if histopathologic findings support such a suspicion.

- Metastatic disease to the head and neck region may be to lymph nodes, bone, soft tissues, dura, and meningeal and perineural and/or perivascular.

BONE METASTASES

Critical Clinical Considerations

Metastases to the extracranial head and neck structures can present both diagnostic and therapeutic dilemmas. This chapter focuses on bone metastases, since outside of to spread to lymph nodes, this is the most common source of metastatic disease to the head and neck region from sites below the clavicles. Other pattern of metastases are summarized in this chapter but are discussed in detail in others.

Metastases to the bone and other extranodal sites of the head and neck are almost always from distant sites or the result of systemic malignancies such as leukemia and plasma cell dyscrasias discussed in Chapter 28 and lymphoma in Chapter 27. They are only rarely from a head and neck primary tumor. The calvarium and brain and cervical spine are frequently involved but are not the primary focus of this discussion.

If the patient has no known primary, the metastatic lesion may be the first presentation of a malignancy and therefore initially considered to be a lesion of head and neck origin.1 This is especially true if subtle differences between a solitary metastases and more usual pathologies go unrecognized or are somehow discounted in the diagnostic process (Figs. 42.1 and 42.2). Such an assumption can lead to very unfortunate medical decision making, and in any unusual lesion a history of even remote treatment for cancer and anticipated cure should be sought. More typically, there is a history of treated cancer. The pattern of the disease may be so characteristic that taken with other factors such as the patient’s age make the diagnosis almost certain (Fig. 42.3). Metastatic disease can also mimic systemic and localized inflammatory conditions. The presenting system commonly is a localized pain or mass (Fig. 42.4) or mass effect (Fig. 42.5). More specific findings such as symptoms and physical findings of isolated (Figs. 42.6 and 42.7) or multiple cranial neuropathies are not uncommon presentations (Fig. 42.8). A multiplicity of lesions, understanding particular pathoanatomic patterns of disease as seen on imaging studies that suggest metastatic disease, and histopathology usually get the thinking pointed in the right direction.

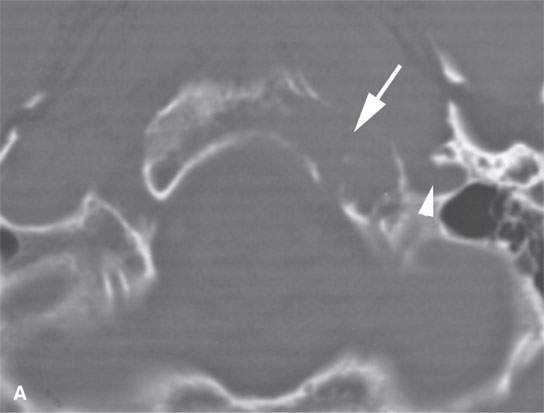

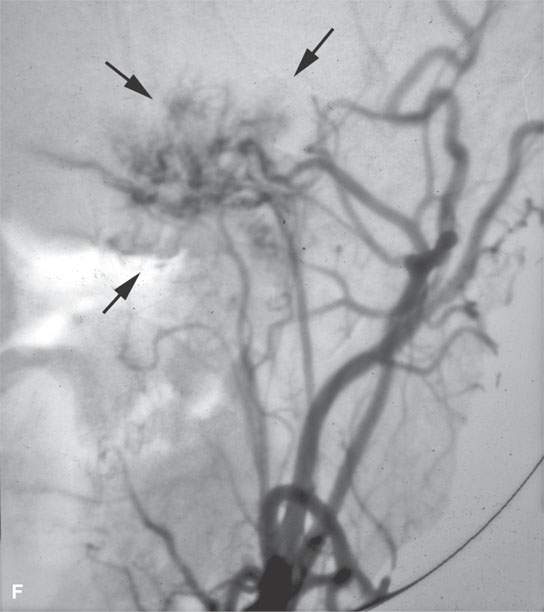

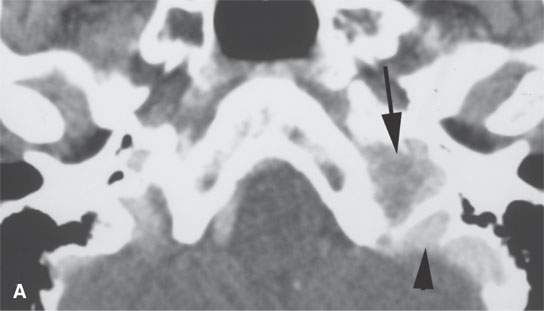

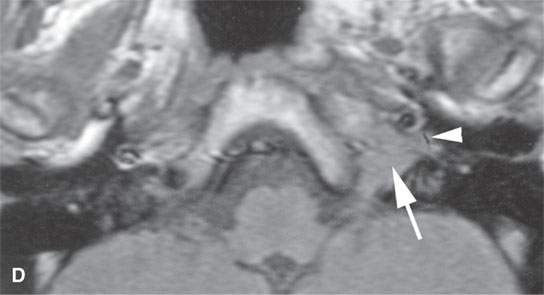

FIGURE 42.1. Patient presenting with multiple lower cranial nerve deficits and otalgia. Patient subsequently underwent computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging, and angiography, which are all shown here. Original presenting diagnosis to our institution was glomus jugulare tumor. Metastasis was subsequently proven as the correct diagnosis. A: CT study at bone windows shows a destructive lesion centered in the base of the occipital bone (arrows) rather than the jugular fossa (arrowhead). B: T1-weighted (T1W) image showing mass replacing the marrow in the lower clivus (arrows). C: Contrast-enhancedT1W image showing the mass to homogeneously enhance fairly intensely (arrows). D: T2-weighted images show the mass to be inhomogeneous but generally isointense to brain with areas likely of necrosis more intense. E, F:Angiography showed the lesion (arrows) to be hypervascular. (NOTE:The position of the mass excludes paraganglioma as a reasonable diagnosis. The vascularity suggested a hypervascular metastasis. Abdominal CT study showed renal cell carcinoma as the primary site for this metastatic lesion.)

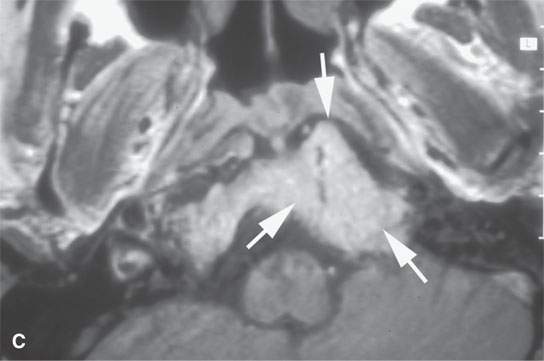

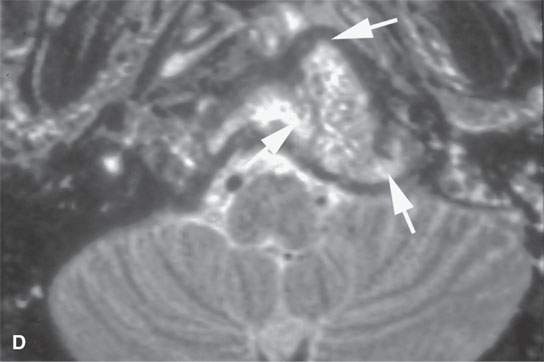

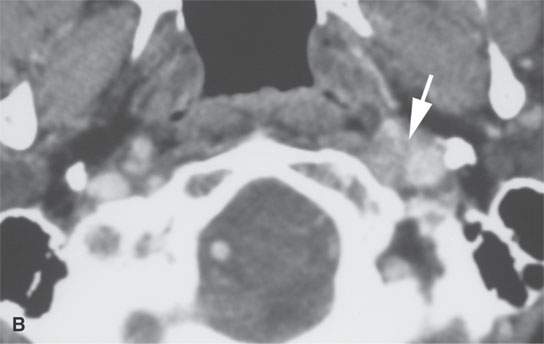

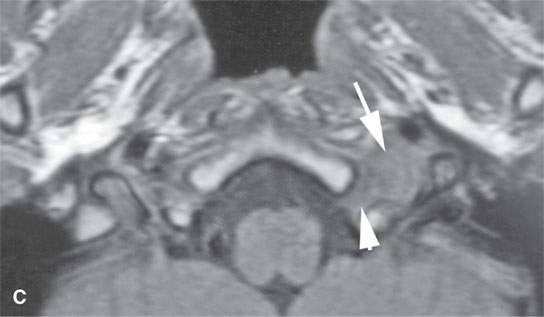

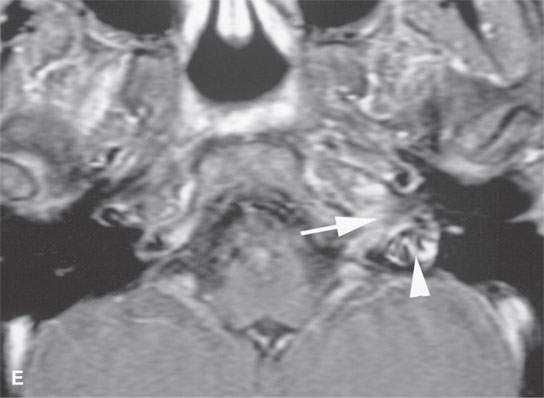

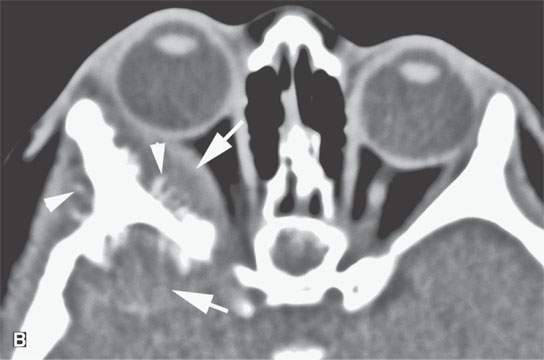

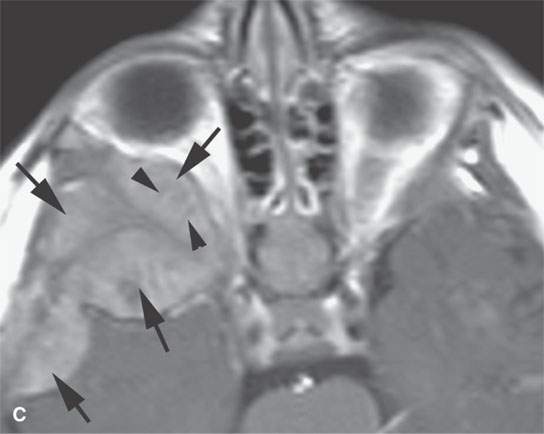

FIGURE 42.2. Patient presenting with lower cranial nerve deficits on the left side and otalgia. A:–Contrast-enhanced computed tomography image shows an enhancing lesion involving the skull base (arrow) anterior to but not obviously destroying the jugular fossa (arrowhead). B: View just below the skull base shows the mass encasing the structures of the carotid sheath (arrow). This explained the lower cranial nerve deficits. C: T1-weighted (T1W) image without contrast showed the mass to be infiltrating below the skull base, encasing the carotid artery (arrow) and invading the hypoglossal canal. The main presenting symptom in this patient was tongue weakness. D: T1W image showing continued extension of the mass (arrow) into the hypotympanum (arrowhead). This created the impression of a possible paraganglioma, but note the lack of any flow voids in any of the previous images and sparing of the jugular fossa. E: Contrast-enhancedT1W gradient echo image showing the jugular vein to be patent and not obviously compressed (arrowhead) and the adjacent mass (arrow). (NOTE:This mass was originally interpreted as a paraganglioma. However, the pattern of involvement is somewhat atypical. The morphology is also somewhat atypical. Biopsy showed this to be metastases due to lung carcinoma.)

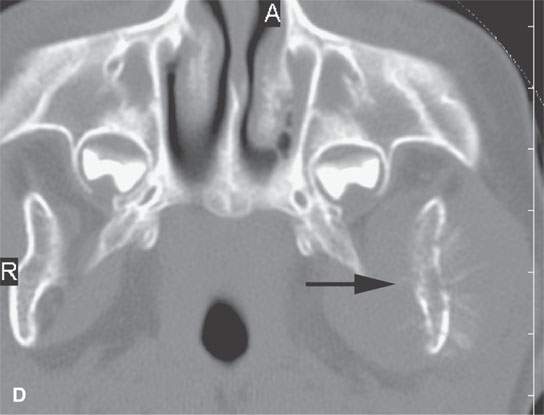

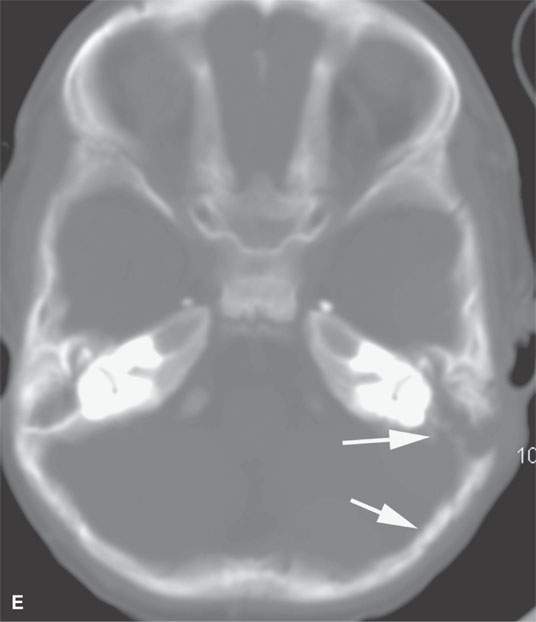

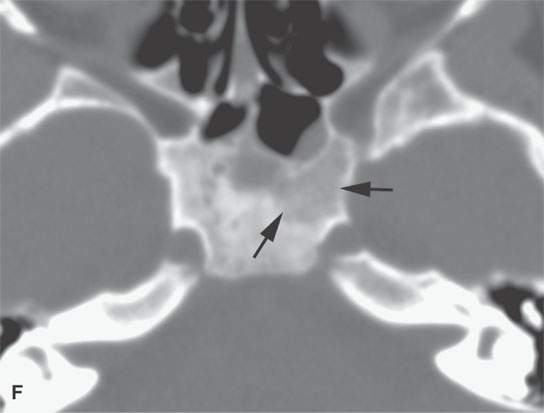

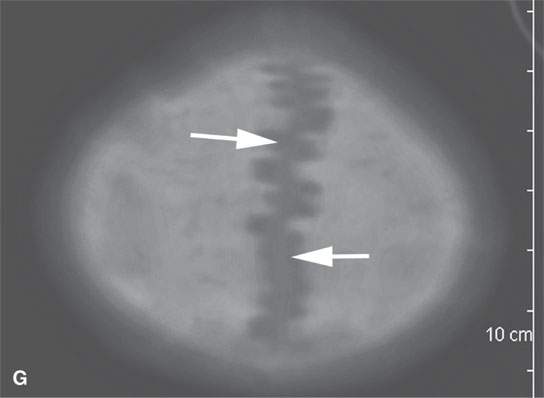

FIGURE 42.3. A patient with metastatic neuroblastoma. A: Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) showing extensive bony metastases bilaterally with related soft tissue extension. B: Soft tissue windows from the CECT study to show the soft tissue mass (arrows) and fairly common spiculated periosteal reaction (arrowheads). C: Contrast-enhancedT1-weighted image for correlation with (aA) and (B) shows the soft tissue mass (arrows) and only a vague indication of the spiculated periosteal changes (arrowheads). D: Bone windows showing mandibular metastasis with fairly typical aggressive bony changes (arrows). E: Metastasis to the mastoid has an appearance much like would be seen in primary rhabdomyosarcoma or Langerhans histiocytosis; if this were a solitary lesion, the differential diagnosis would be more difficult. F: Computed tomography of the skull base to show how metastases might vary in morphology in any given patient (arrows). G: Widening of the sutures related to metastatic disease (arrows).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree