LEARNING OBJECTIVES

1. Describe the appropriate evaluation of breast calcifications that cannot be classified as benign on screening images

2. Features of benign breast calcifications and appropriate descriptors

3. Descriptors used for the distribution of breast calcifications

4. Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS)

• Heterogeneity of the disease

• Presentations

• Imaging features

5. Features of calcifications associated with DCIS characterized by central necrosis

6. Features of calcifications that develop in secretions associated with proliferative changes in the ducts (hyperplasia, atypical ductal hyperplasia, low grade DCIS; columnar cell change)

Calcifications developing in the breast and detected on screening mammograms are variable in number and appearance, and most reflect a benign etiology. A small number develop in association with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), less commonly the invasive component of ductal carcinomas or in metastatic disease to the breast or axillary lymph nodes (e.g., psammoma bodies—ovarian or thyroid carcinomas) (see Fig. 8.56). It is incumbent upon the radiologist to detect, evaluate, classify, and make appropriate recommendations for calcifications perceived on mammograms for which, in most patients, there is no clinical correlate.

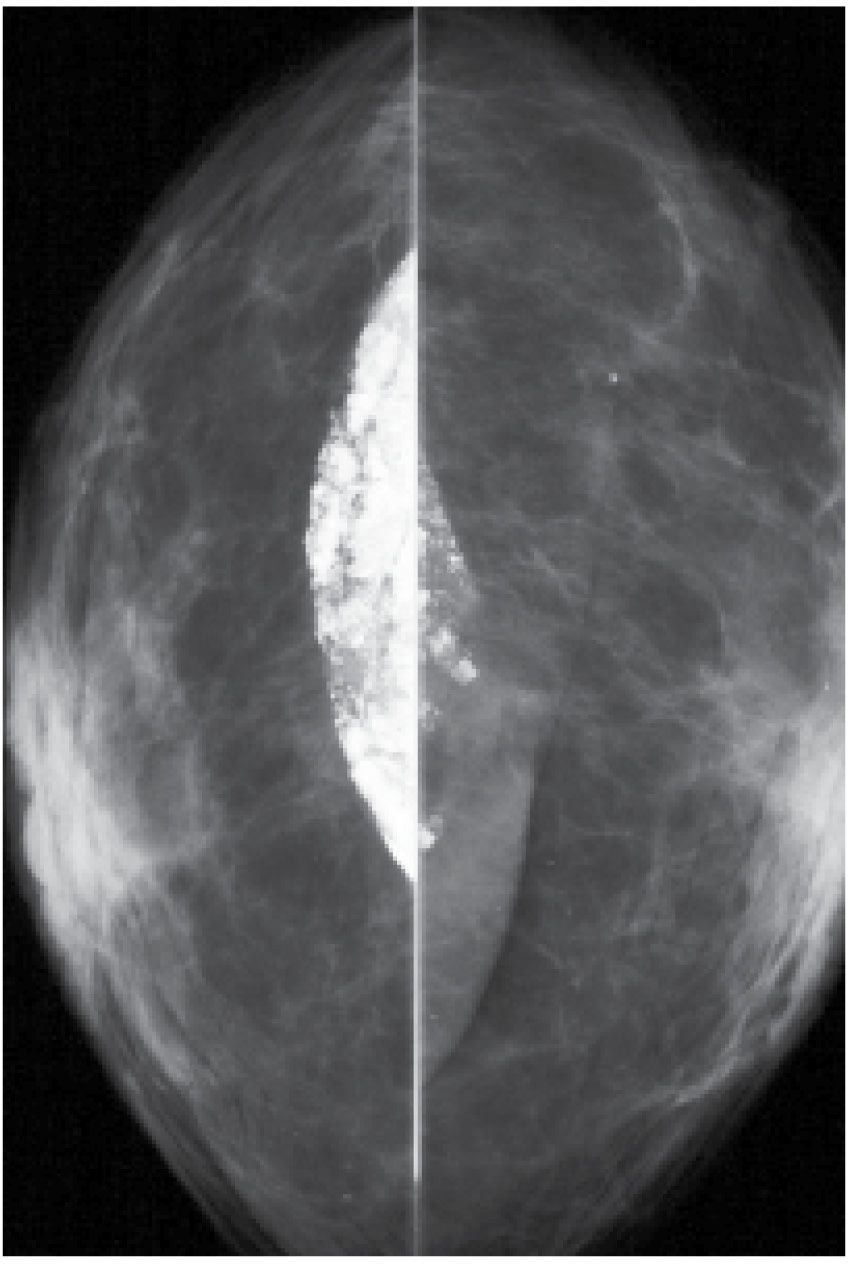

Complete mammographic workups that include spot compression magnification views in two projections with no motion, coupled with knowledge of breast anatomy and histopathology, are critical in understanding the mammographic appearance of breast calcifications and establishing appropriate and justifiable recommendations. Calcifications developing in a space (i.e., ducts or acini) are molded by that space. Calcifications arising in ducts are tube-like or linear and may demonstrate linear distribution. If they develop in subsegmental ducts, they are large, rod-like, and dense compared with the smaller calcifications of variable density that develop in terminal ducts. When the epithelial lining is attenuated or denuded, the border of the calcifications is smooth (Fig. 6.1) compared with the irregular margins that may be seen when there is active cellular proliferation and necrotic debris in the lumen of the duct (Fig. 6.2). Calcifications forming in acini are round or punctate (Fig. 6.3). If the normally round acini are compressed, elongated, or deformed by proliferation of the surrounding perilobular stroma, the calcifications may demonstrate pleomorphism, including round, punctate, oval, and comma-shaped forms.

As discussed in Chapters 2 and 3, establishing optimal film quality is one of the initial steps in reviewing screening and diagnostic mammograms. Well-exposed, high-contrast images with optimal positioning and no blurring are essential in maximizing our ability to detect microcalcifications, small spiculated masses, and subtle areas of distortion. The acceptance and interpretation of suboptimal films can result in a delay in the diagnosis of breast cancer. With respect to calcifications in particular, generalized or localized blurring on an image can lead to a failure to detect calcifications, or if noted, the morphology of the calcifications may be grossly distorted, potentially resulting in a misdiagnosis (see Fig. 2.24).

When evaluating calcifications, consider the following characteristics: What is the predominate form of the individual calcifications? Round or linear, coarse or fine (granular), monomorphic or pleomorphic (heterogeneous), or within a cluster? Monomorphism is not common. Pleomorphism and heterogeneity are seen in most groups of calcifications even when related to a benign etiology. What is the size of the calcifications? Large or small and, if in a cluster, are the individual calcifications homogeneous in size? What is the density of the calcifications? High or low? In a given cluster is there homogeneity in density among the individual calcifications? What is the distribution of the calcifications? Unilateral or bilateral, single cluster or multifocal, diffuse, regional, segmental, or linear? Calcifications that are diffusely scattered in dense tissue bilaterally are typically benign in contrast to linear calcifications in a linear or segmental distribution. Are the calcifications new compared with prior studies, and if so, where in the breast are the calcifications developing?

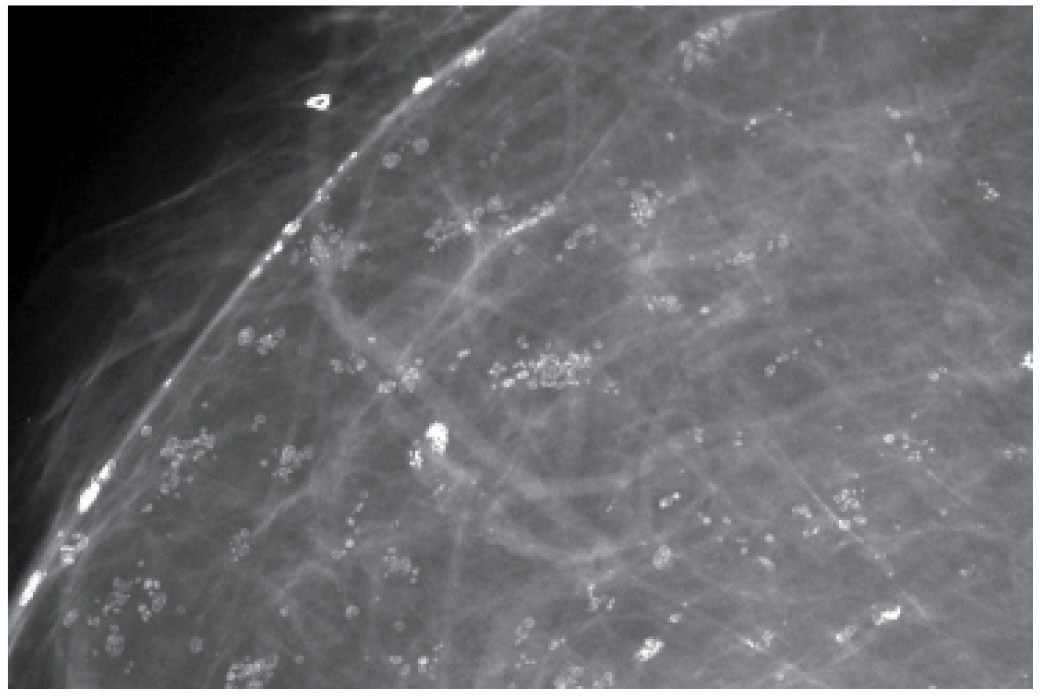

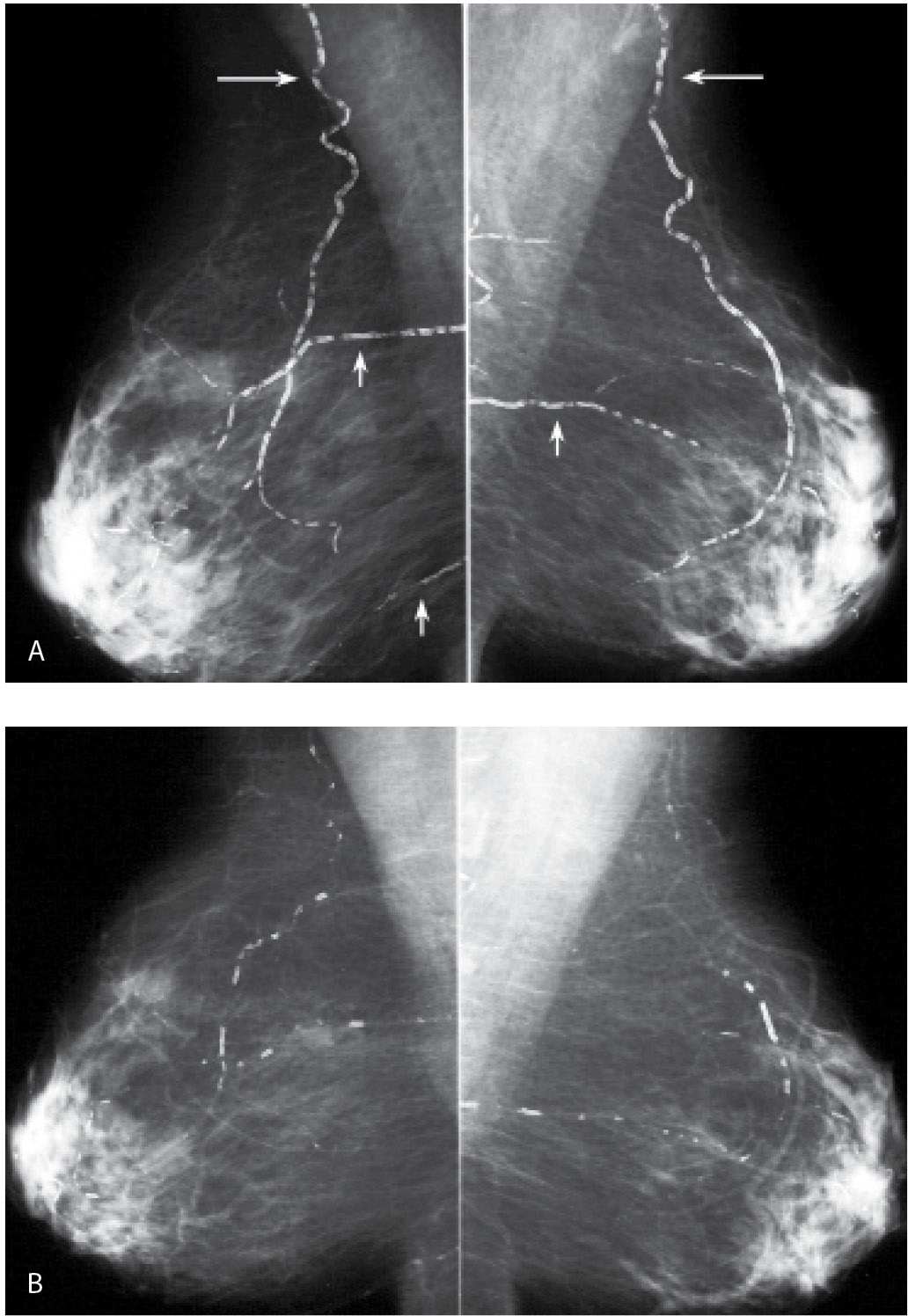

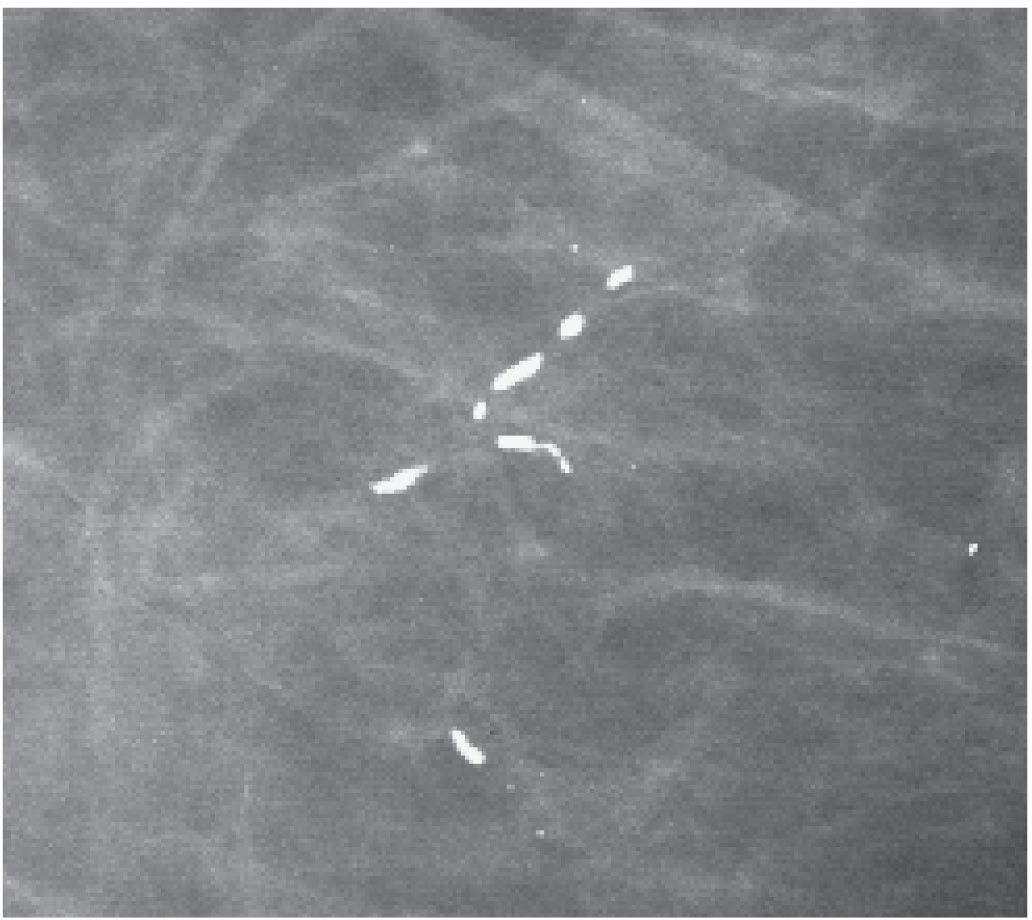

FIG. 6.1 • Rod-like calcifications. Forming in subsegmental ducts, these calcifications are dense, rod-like, and linearly oriented toward the nipple. The smooth border of the calcifications reflects a denuded or attenuated epithelial lining in the ducts. They are often identified bilaterally usually with no round, punctate, or amorphous forms in the neighborhood. BI-RADS 2: Benign finding. (From Cardeñosa G. Breast Imaging [The Core Curriculum Series]. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.)

The emphasis placed previously on the number of calcifications in a given cluster, in our opinion, is not a particularly helpful characteristic. One or two linear calcifications with irregular margins may be related to the presence of DCIS and require a biopsy. Conversely, a tight cluster of many round, pearl-like calcifications of homogeneous density does not usually require a biopsy. There is no question that calcifications related to an underlying DCIS tend to be numerous with variation in form (e.g., linear forms are commonly surrounded by punctate and amorphous forms as well as some larger, dense, coarse calcifications), density and distribution. So it is important to look at not only the individual calcifications, but also the neighborhood in which they reside.

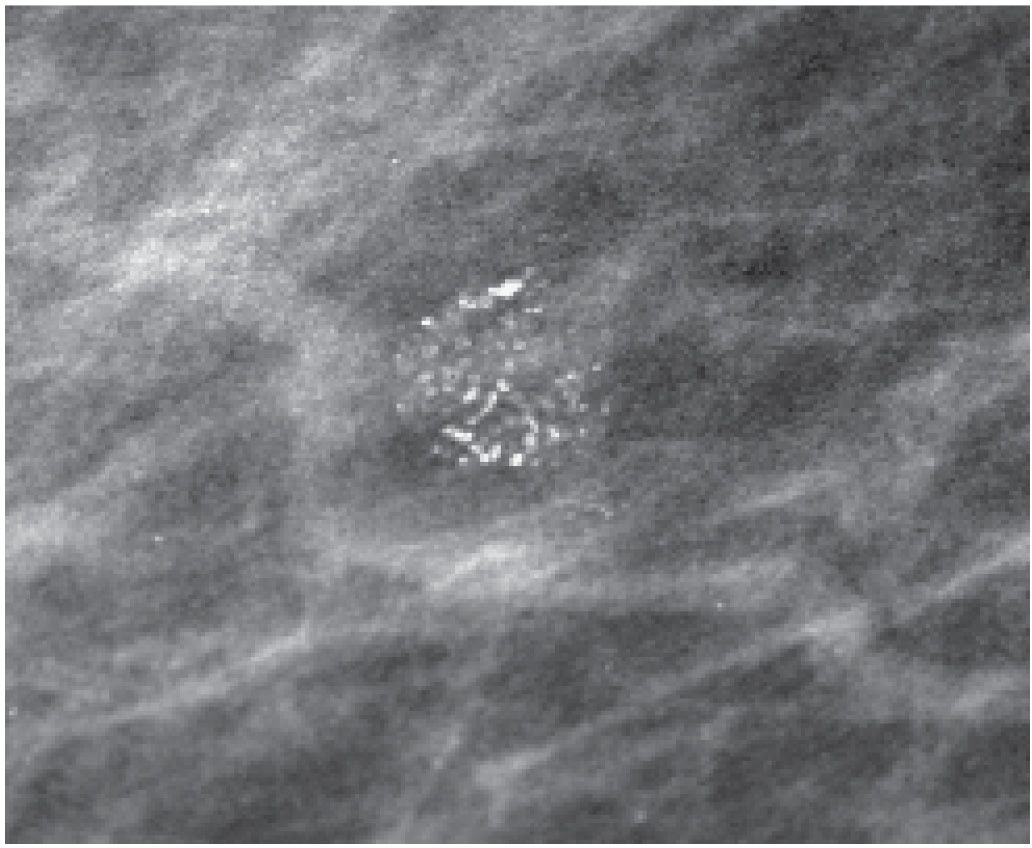

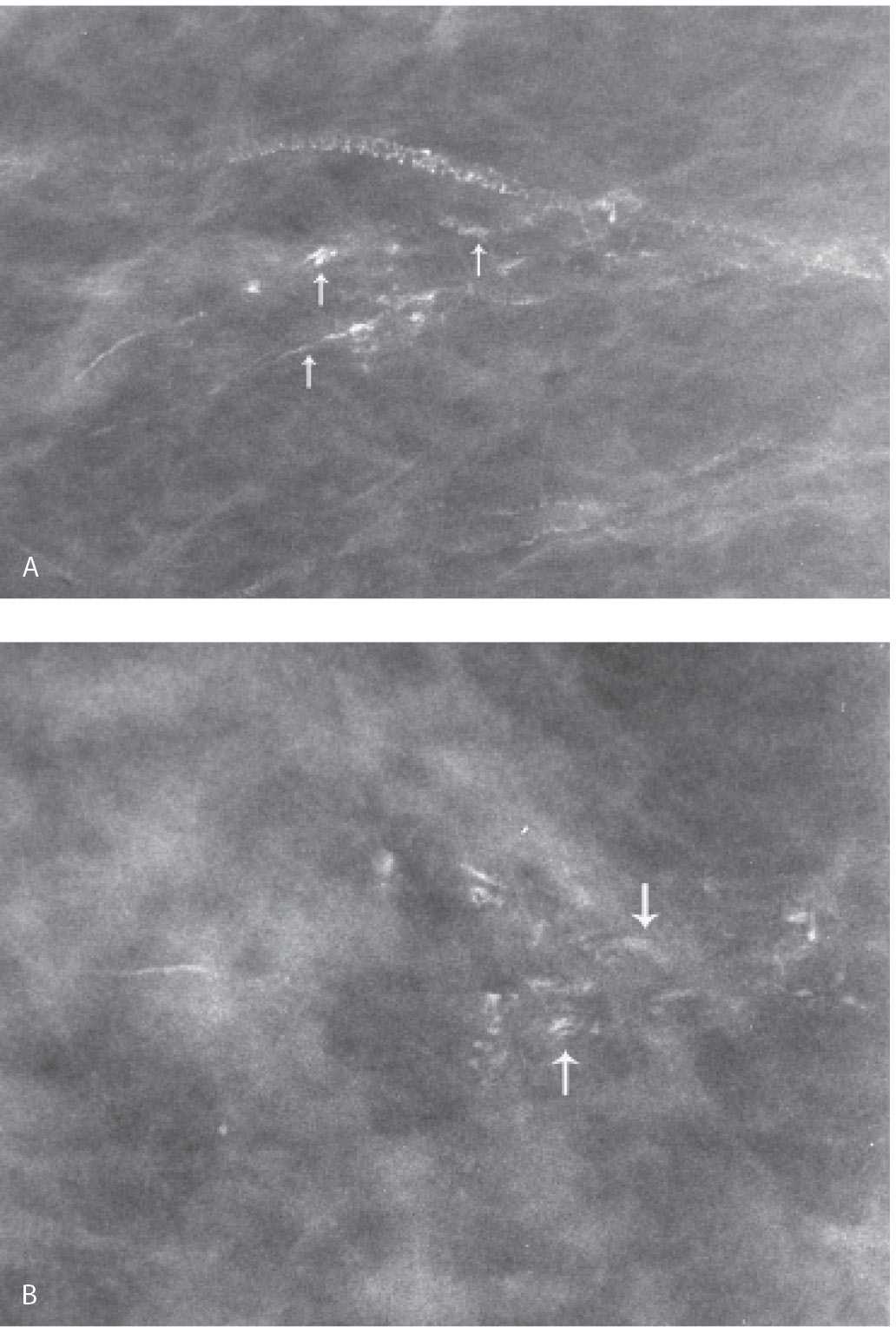

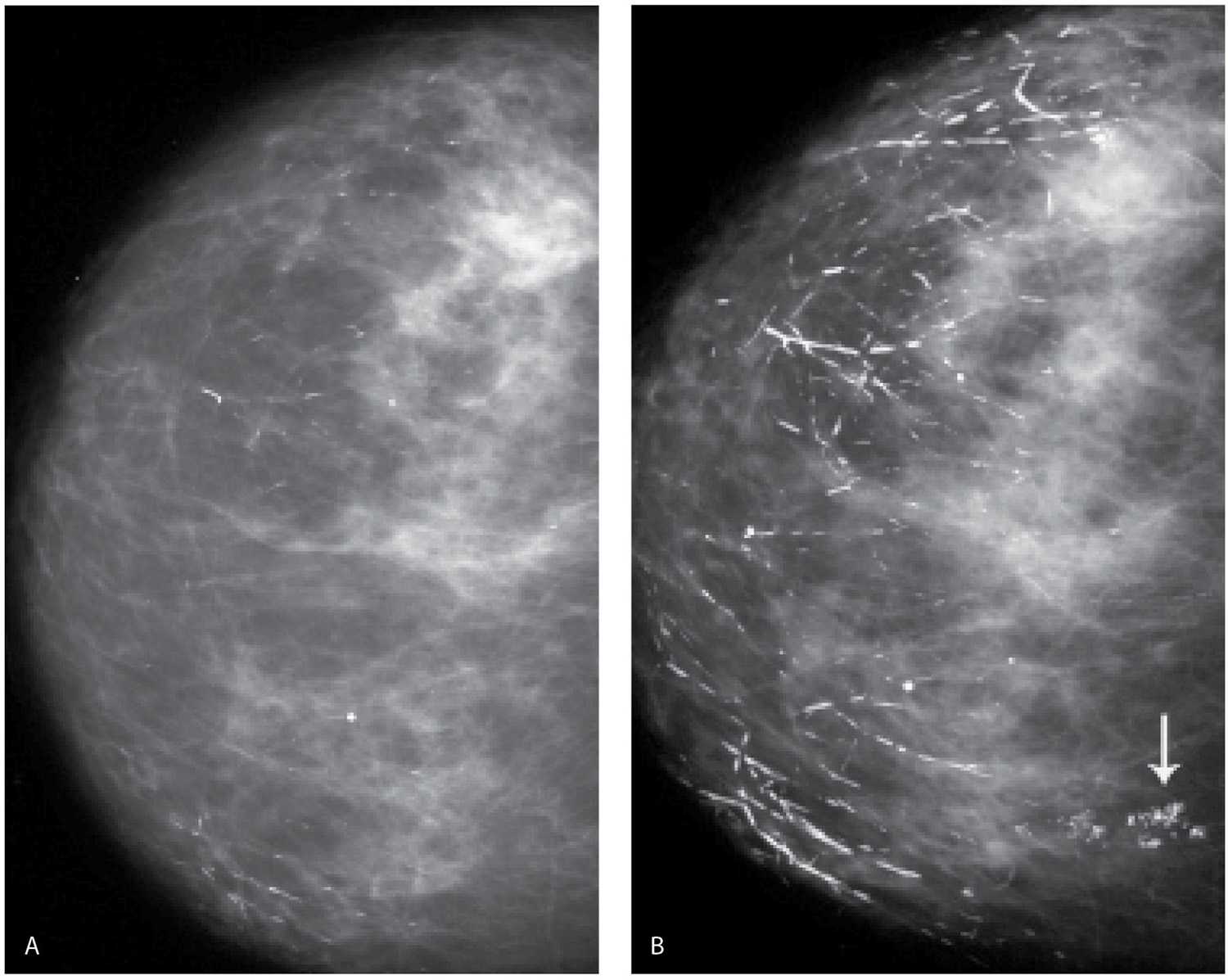

The presence of linear calcifications with irregular borders, variable density, and linear orientation that are grouped, haphazardly or segmentally distributed needs to be considered significant (Figs. 6.2 and 6.4) (1–3). The likelihood of an underlying DCIS (low, intermediate, or high nuclear grade) associated with central necrosis is high; biopsy is indicated in these patients. These types of calcifications are fairly distinctive and uncommonly associated with benign processes, including those listed in Table 6.1. We also consider the linear distribution of round, oval, punctate (fine pleomorphic; coarse heterogeneous), or amorphous calcifications with variable density as an indication for biopsy (Fig. 6.5). However, in the absence of linear calcifications or a linear distribution, the likelihood of DCIS drops significantly and, when diagnosed, is usually, though not exclusively, low or intermediate grade DCIS with no central necrosis. Diagnostic considerations for groups of round, oval, punctate (Fig. 6.6), and amorphous calcifications (4,5) include those listed in Table 6.2.

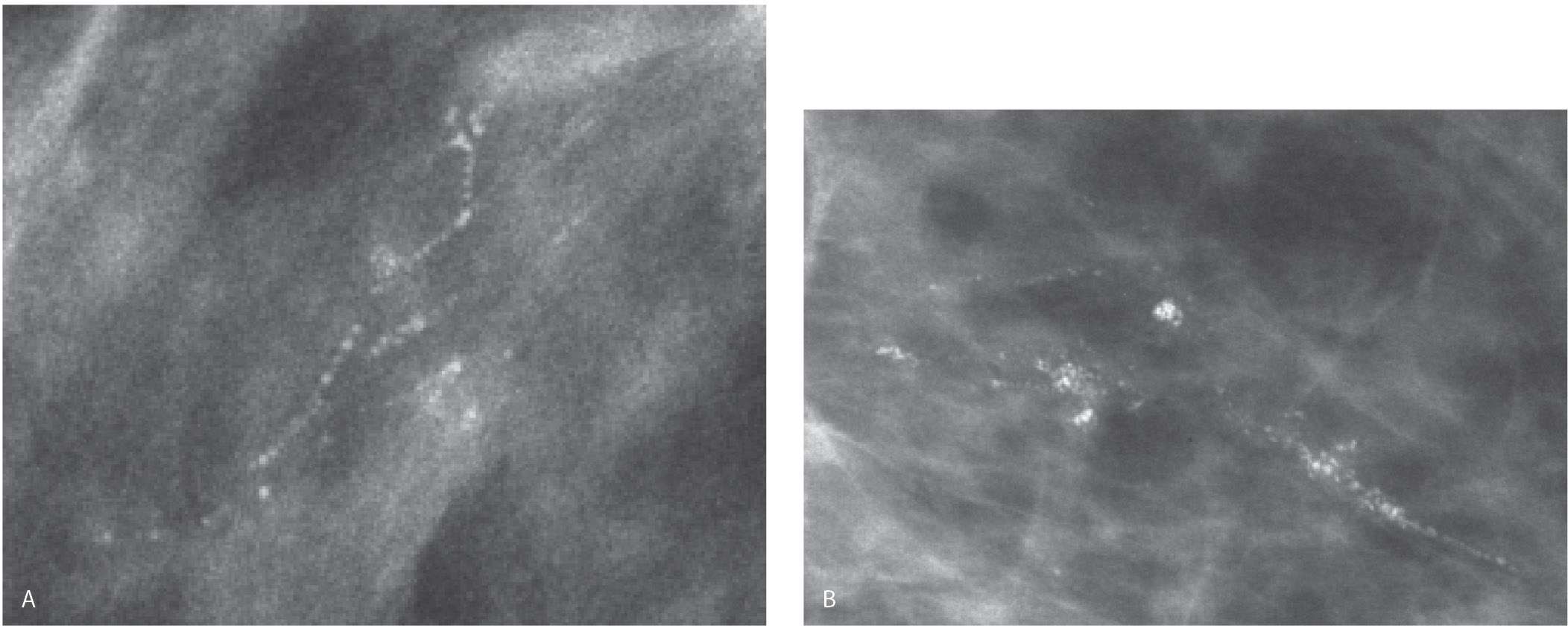

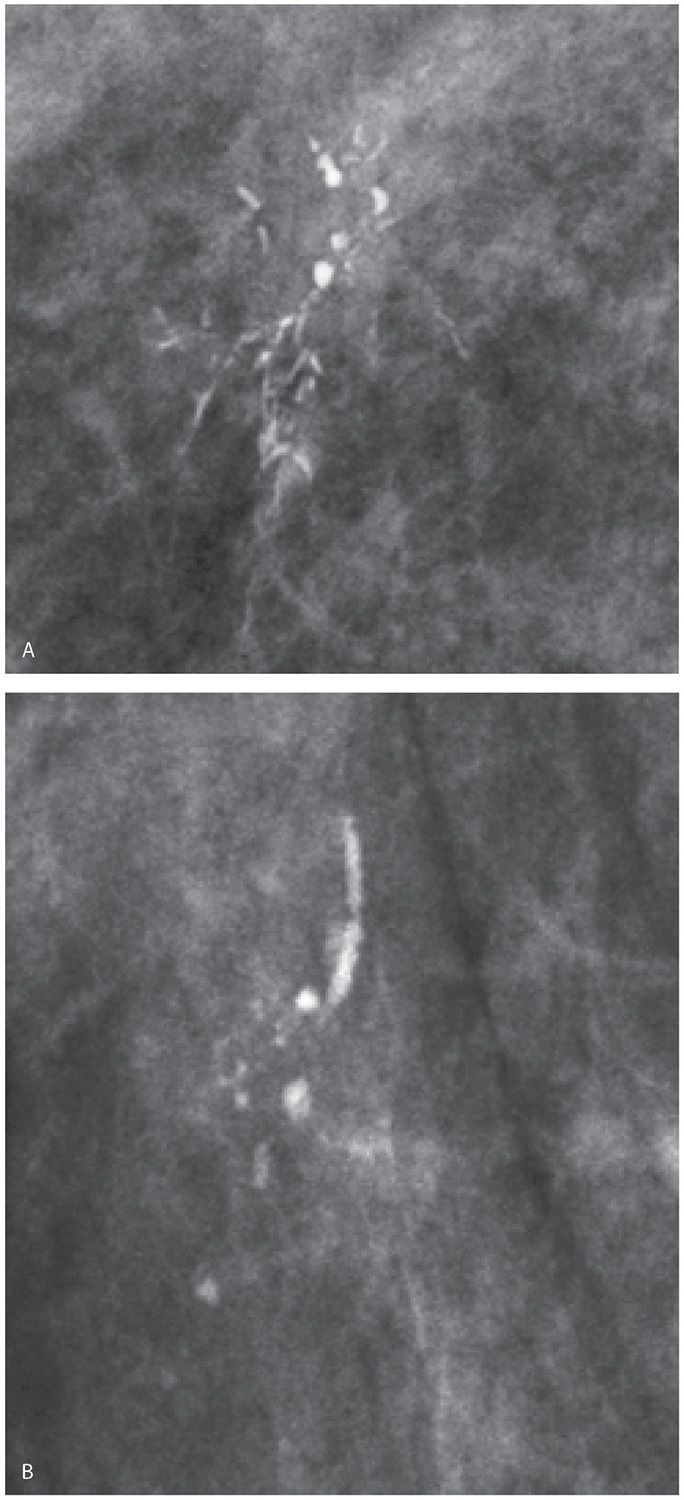

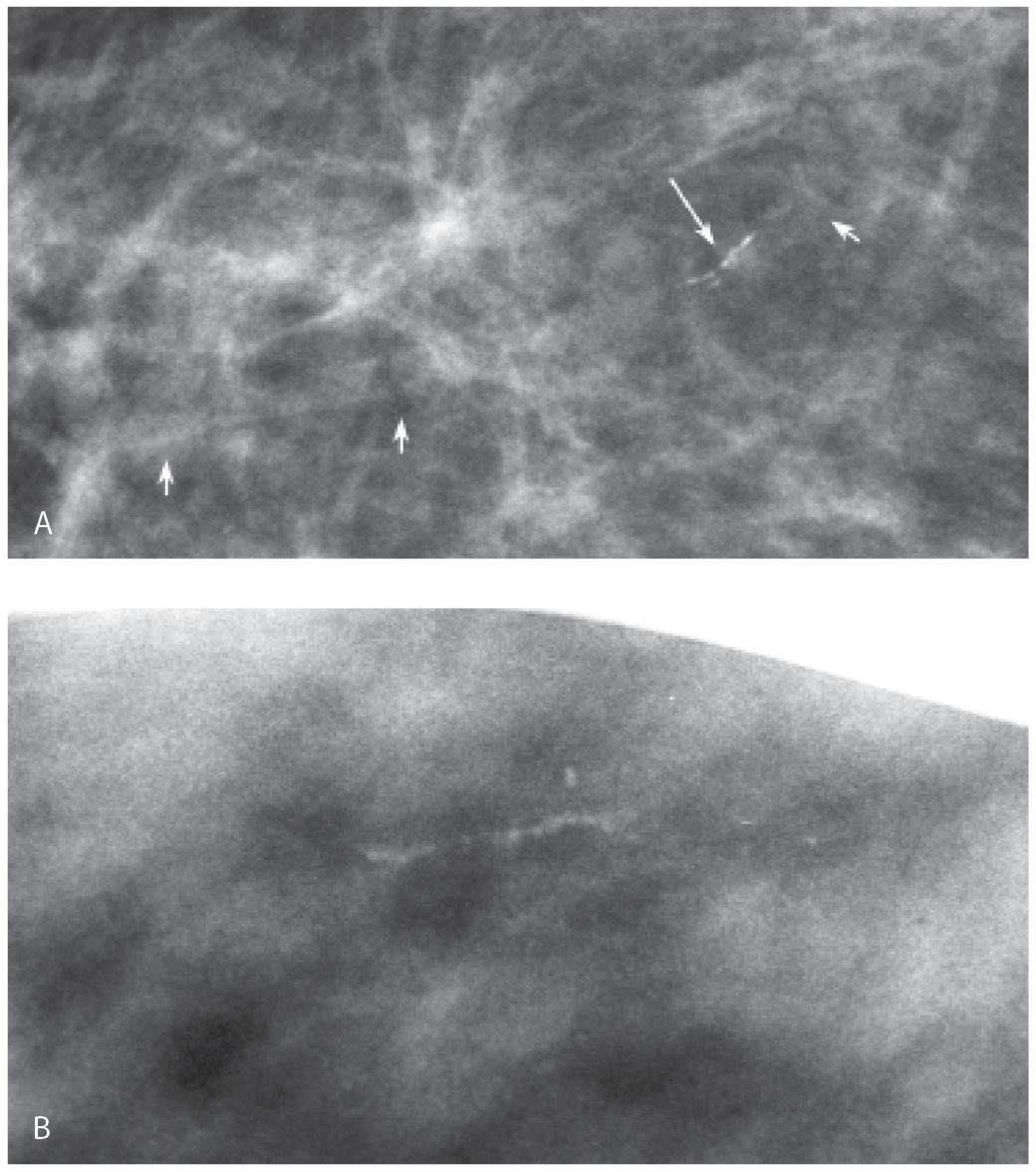

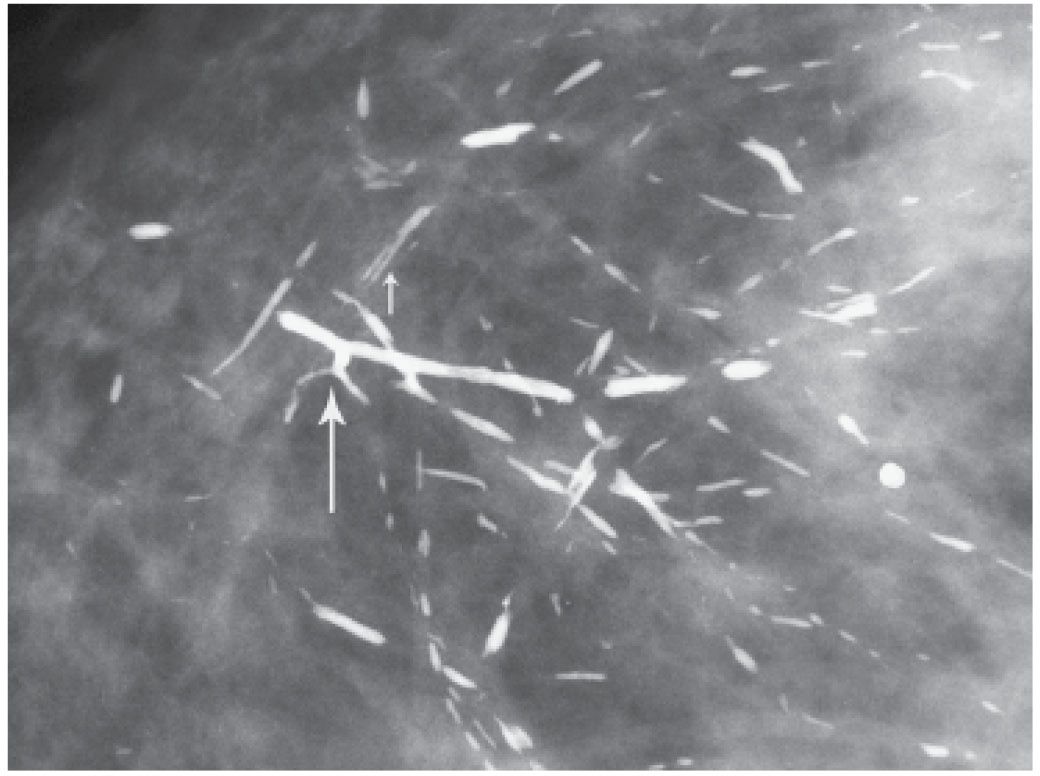

FIG. 6.2 • Linear calcifications in a linear distribution, DCIS. A: Spot compression magnification view. Group of calcifications that includes linear calcifications in a linear (ductal) distribution as well as coarse dense heterogeneous calcifications. Note that the density of the calcifications is variable. BI-RADS 4C: Suspicious abnormality, biopsy is indicated. B: Spot compression magnification view. Group of calcifications that includes linear calcifications in a linear distribution as well as coarse heterogeneous calcifications. Note the irregular margins of the linear calcifications. These calcifications develop in necrotic cellular debris deposited in the lumen of dilated ducts and are molded by the proliferating epithelial cells. BI-RADS 4C: Suspicious abnormality, biopsy is indicated. Although not pathognomonic of DCIS, be careful before accepting a benign histology for calcifications having these morphologic features.

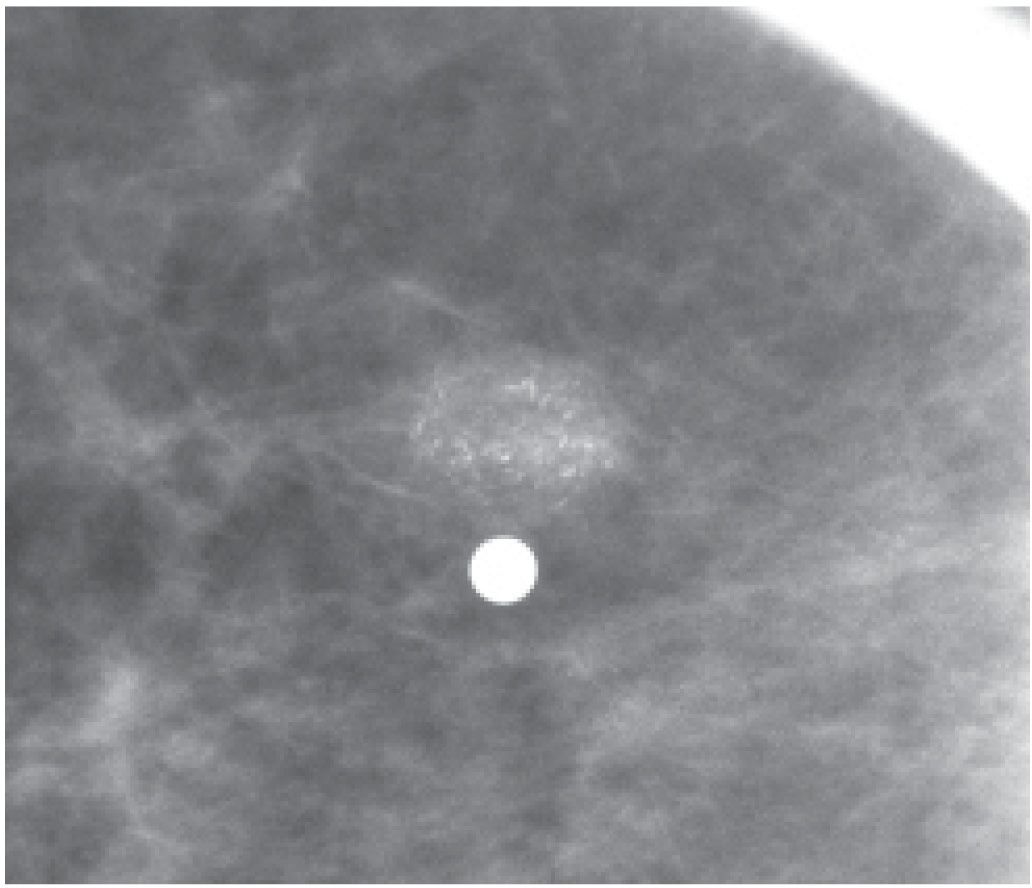

FIG. 6.3 • Round and punctate calcifications. Lobular. This group of calcifications is characterized by relatively monomorphic round and punctate calcifications having some variation in density. No linear forms or linear orientation is seen. BI-RADS 2: Benign finding. (From Cardeñosa G. Breast Imaging [The Core Curriculum Series]. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.)

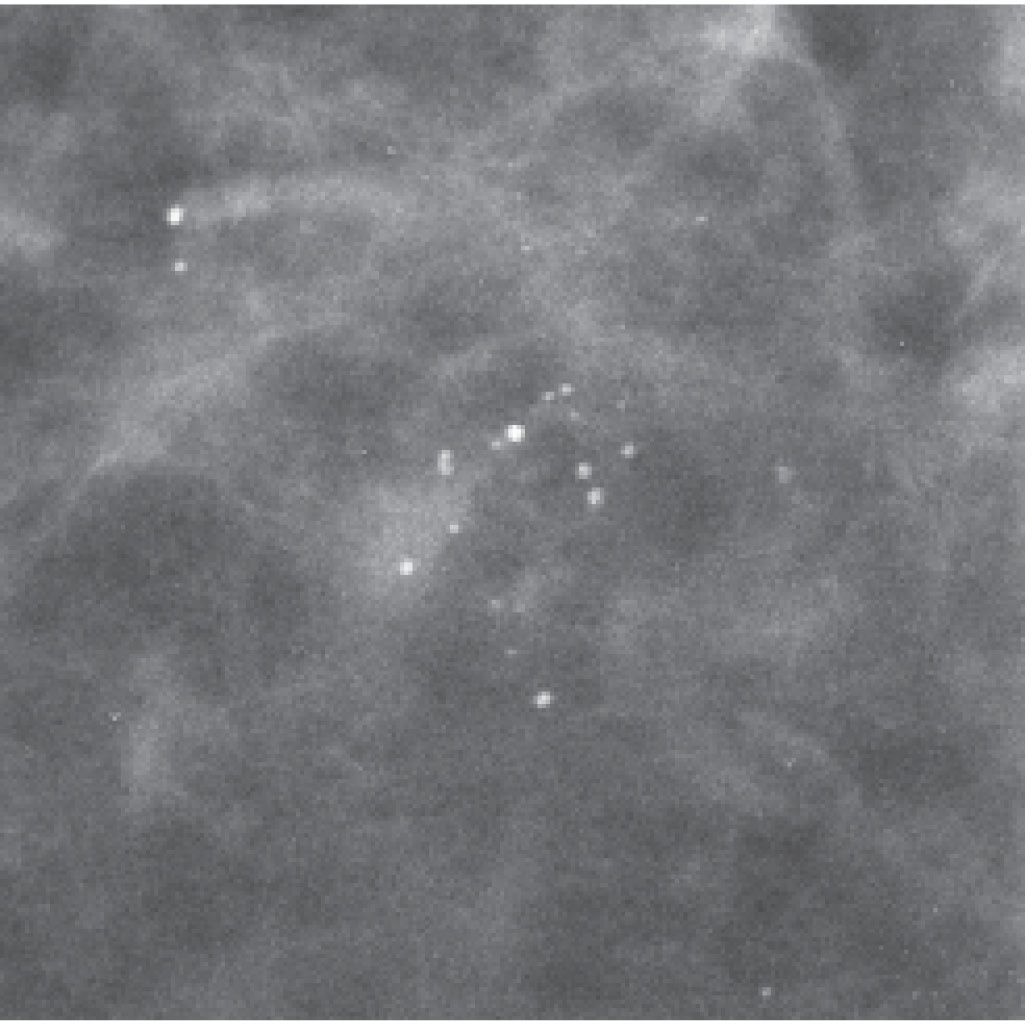

FIG. 6.4 • Linear calcifications in a linear (ductal) orientation. DCIS. A: Spot compression magnification view. Dense linear calcifications in a linear (ductal) distribution. BI-RADS 4C: Suspicious abnormality, biopsy is indicated. B: Linear calcifications with irregular margins and clefts in a linear, branching distribution. These calcifications develop in intraluminal necrotic debris, reflective of the ongoing proliferative cellular process. Fine pleomorphic calcifications are also present. BI-RADS 4C: Suspicious abnormality, biopsy is indicated.

Table 6.1 DIFFERENTIAL: FINE, LINEAR, BRANCHING CALCIFICATIONS IN A GROUP OR LINEAR/SEGMENTAL DISTRIBUTION

DCIS (w/central necrosis; commonly high nuclear grade DCIS but can also be seen in approximately 15–20% of low- or intermediate-grade DCIS) Fat necrosis (in the early stages of calcification) Fibroadenoma Dystrophic, fibrosis Autoimmune disorders (dermatomyositis, scleroderma, lupus) Vascular (early stage) Secretory (focal) Suture (cut gut sutures and radiation) Parasites (serpiginous) |

BENIGN BREAST CALCIFICATIONS

For didactic purposes, I take an anatomic approach in describing breast calcifications. The terms provided in the American College of Radiology (ACR) BI-RADS® lexicon (6) for description and distribution modifiers are listed in Tables 6.3 and 6.4, respectively, and used throughout the text. Also please see Appendix A for the ACR BI-RADS® mammography, US and MRI lexicons.

As mentioned previously, when thinking about breast calcifications consider the anatomical structures available for breast calcifications to develop and the potential pathologic processes associated with these structures. This becomes helpful when analyzing calcifications and determining appropriate diagnostic considerations and management. Include the following tissue types: skin, stroma (e.g., fibrous tissue), ducts (large and small), acini grouped into lobules, and arteries. Calcifications developing in masses may be associated with the wall (mural, rim) of the mass, if one is present (e.g., cysts, oil cysts), or the epithelial or stromal elements of the mass. If the mass contains fluid, the calcifications may be in suspension (e.g., milk of calcium). Rarely, calcifications develop in association with foreign bodies such as suture material and parasites.

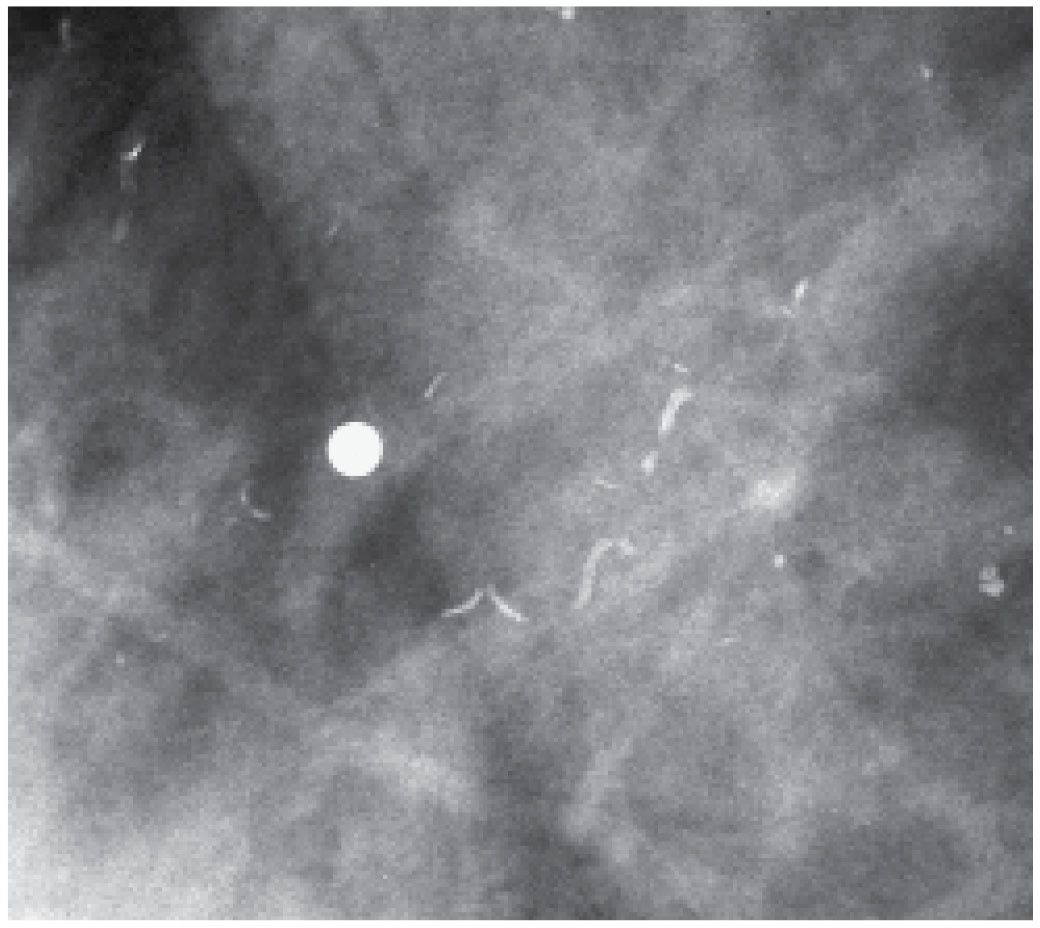

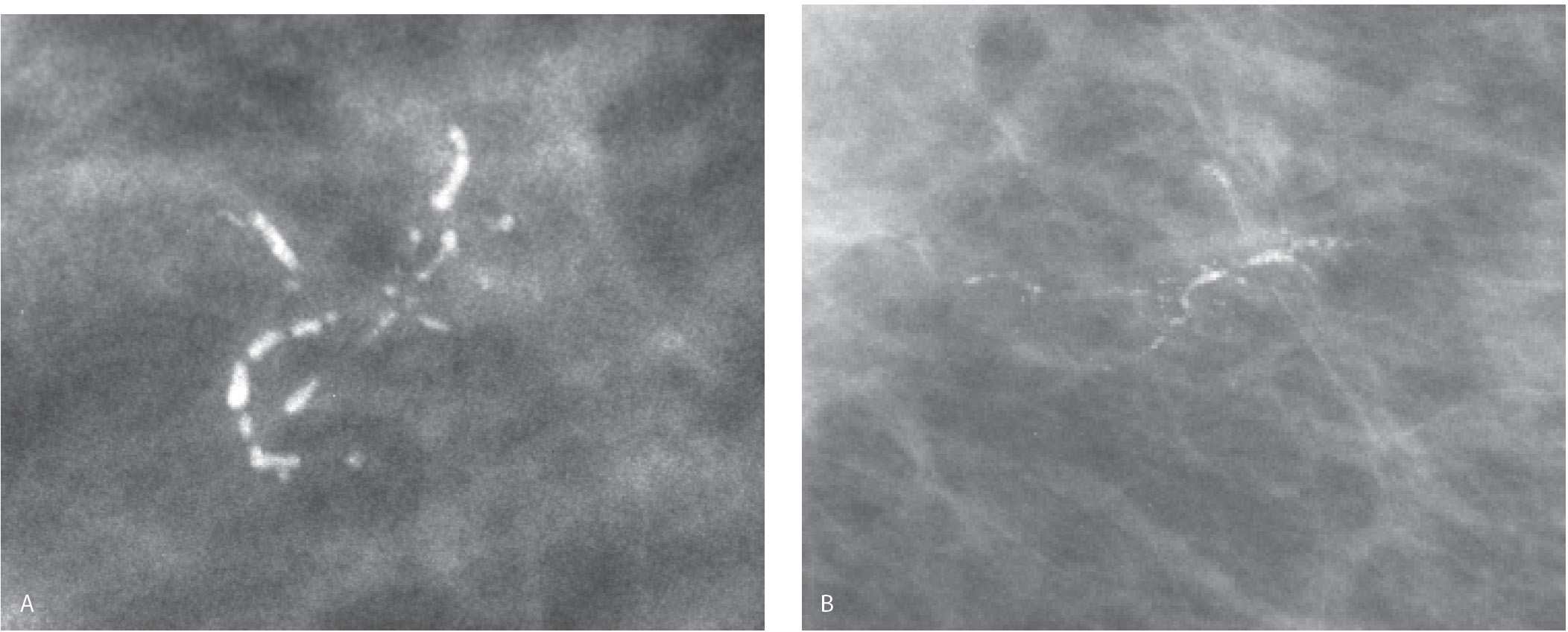

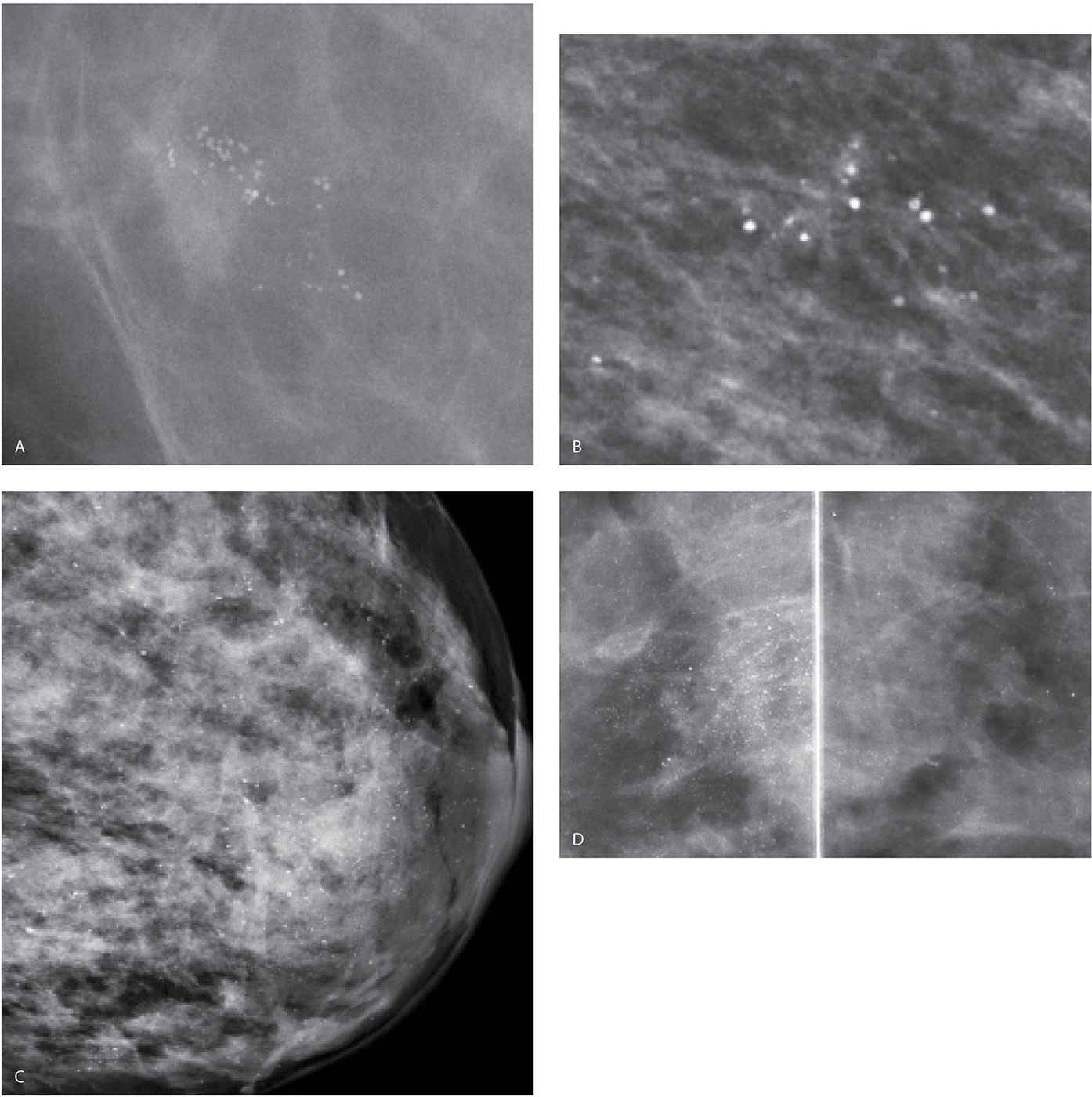

FIG. 6.5 • Linear (ductal) distribution. DCIS. A: Coarse heterogeneous and fine pleomorphic calcifications in a linear distribution (“string of pearls”). No linear forms are identified; however, the linear (ductal) distribution of the calcifications warrants biopsy. BI-RADS 4B: Suspicious abnormality, biopsy is indicated. DCIS, low nuclear grade, cribriform is diagnosed on core biopsy and confirmed on the lumpectomy specimen. B: Fine pleomorphic calcifications with intermingled coarse heterogeneous calcifications in a linear or segmental distribution. Linearly or segmentally distributed calcifications with the features shown warrant biopsy. BI-RADS 4C: Suspicious abnormality, biopsy is indicated. DCIS, high nuclear grade comedo-type is diagnosed on core biopsy and confirmed on the lumpectomy specimen.

FIG. 6.6 • Round and punctate calcifications. Group of predominantly round calcifications with similar density, no linear forms or linear orientation. These may be considered “probably benign” if no prior films are available for comparison. BI-RADS 3: Probably benign finding; however, we recommend follow-up in 1 year for patients with these types of calcifications (e.g., no 6-month follow-up). (From Cardeñosa G. Breast Imaging [The Core Curriculum Series]. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.)

SKIN CALCIFICATIONS

Skin calcifications (Fig. 6.7) form in sweat glands following low-grade folliculitis and inspissation of sebaceous material. Consequently, they are round or oval, lucent-centered, isolated, or more commonly, multiple tight clusters bilaterally. A lace-like pattern can be seen when associated with moles (see Fig. 7.8A). In lucent-centered skin calcifications, a punctate calcification may be seen centrally. Commonly, skin calcifications are seen posteromedially projecting on the pectoral muscles on mediolateral oblique (MLO) views, and medially at the cleavage, on craniocaudal (CC) views (Fig. 6.8); they can also involve the skin diffusely. In patients who have had a reduction mammoplasty, skin calcifications sometimes develop along the incisions, demonstrating a linear distribution.

Table 6.2 GROUPS OF FINE PLEOMORPHIC (PUNCTATE, ROUND, OR AMORPHOUS CALCIFICATIONS) AND COARSE HETEROGENEOUS CALCIFICATIONS

Lobular calcifications Fibroadenoma Papilloma Fibrocystic changes Sclerosing adenosis Ductal hyperplasia Atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH) Flat epithelial atypia Columnar cell change (CAPPS with or without atypia) Fibrosis Fat necrosis Mucocele-like lesions DCIS (more commonly low or intermediate cribriform, micropapillary DCIS w/no central necrosis) |

Table 6.3 ACR LEXICON, DESCRIPTIVE TERMS FOR CALCIFICATIONS

Benign | Suspicious |

Skin | Amorphous |

Vascular | Coarse heterogeneous |

Coarse or popcorn-like | Fine pleomorphic |

Large rod-like | Fine linear or fine-linear branching |

Round |

|

Rim |

|

Milk of calcium |

|

Suture |

|

Dystrophic |

|

Table 6.4 ACR LEXICON, DISTRIBUTION MODIFIERS FOR CALCIFICATIONS

Grouped Linear Segmental Regional Diffuse |

FIG. 6.7 • Skin calcifications. Multiple groups of round and oval lucent-centered calcifications. BI-RADS 2: Benign finding. A micromark biopsy clip is noted subcutaneously.

On any two views of the breast, much of the skin is superimposed on breast parenchyma; only a small amount of skin is ever in tangent to the x-ray beam, enabling distinction between skin and associated lesions from underlying breast tissue (Fig. 6.8). Although the appearance of most skin calcifications is distinctive, if lucent centers are not readily apparent, definitive diagnosis is made when the skin containing the calcifications is imaged in tangent to the x-ray beam (see Fig. 3.25 and Chapter 3 for a description of skin localization) (7–9).

In some patients, calcifications develop in association with moles or other skin lesions (e.g., sebaceous cysts). These can outline the crevices of the mole, creating semicircular, lace-like calcifications, or, when developing in the contents of the mass, they may be pleomorphic (Fig. 6.9) or more coarse and dense (see Fig. 7.13). In some women, talc, Desitin, or other high-density products, deposited in the crevices of moles, can simulate calcifications. The overall density of the particles, their morphology and distribution, is usually pathognomonic (Fig. 6.10); alternatively, placing a metallic BB on the skin lesion and demonstrating that the BB moves with the lesion on two views (Fig. 6.9), obtaining a tangential view of the skin lesion (see Figs. 3.25, 7.9B and 7.11B), or wiping the patient’s skin and repeating an image can provide a definitive diagnosis.

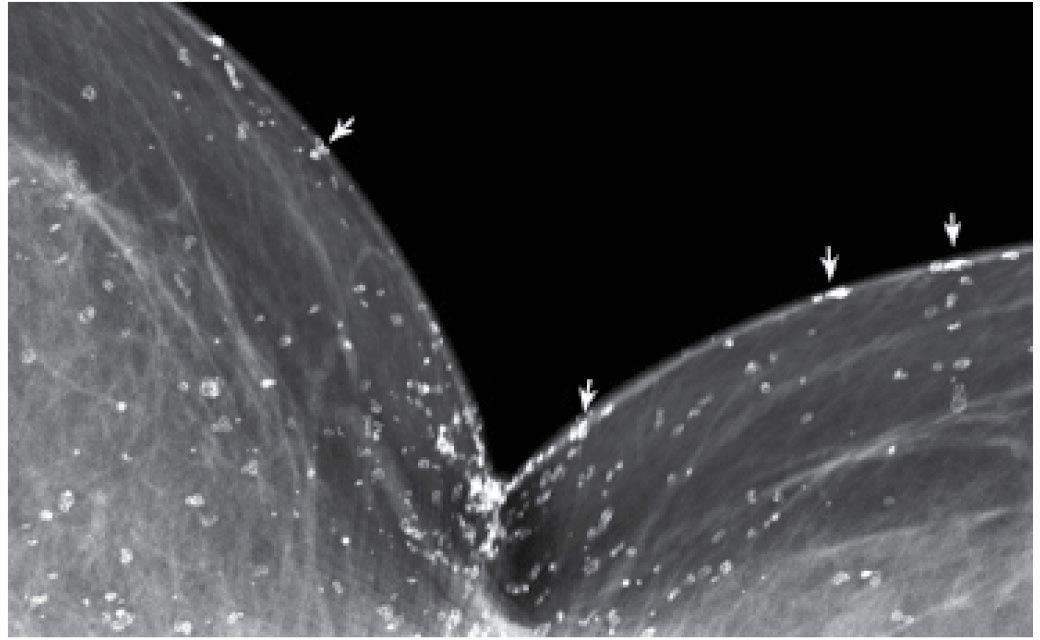

FIG. 6.8 • Skin calcifications. Cleavage view. Many round and oval lucent-centered calcifications are noted posteromedially seemingly in the breast. However, keep in mind that only a small amount of skin is captured in tangent to the x-ray beam. On any image of the breast, most of the skin projects on the breast parenchyma. Those calcifications in the skin that are in tangent to the x-ray beam can be localized to the skin (arrows).

FIG. 6.9 • Skin mass with associated fine pleomorphic calcifications. Metallic BB denotes site of skin lesion. A low-density mass with indistinct margins and fine pleomorphic calcifications is imaged correlating with the site of the skin lesion. BI-RADS 2: Benign finding. (From Cardeñosa G. Breast Imaging [The Core Curriculum Series]. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.)

FIG. 6.10 • High-density particles outlining crevices of skin lesion. Central lucencies are evident. The density of the particles and their morphology are helpful in establishing the benign etiology. If concerns remain, a metallic BB can be placed on the skin lesion, or the skin can be wiped clean and a follow-up image used to establish correlation. (From Cardeñosa G. Breast Imaging [The Core Curriculum Series]. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.)

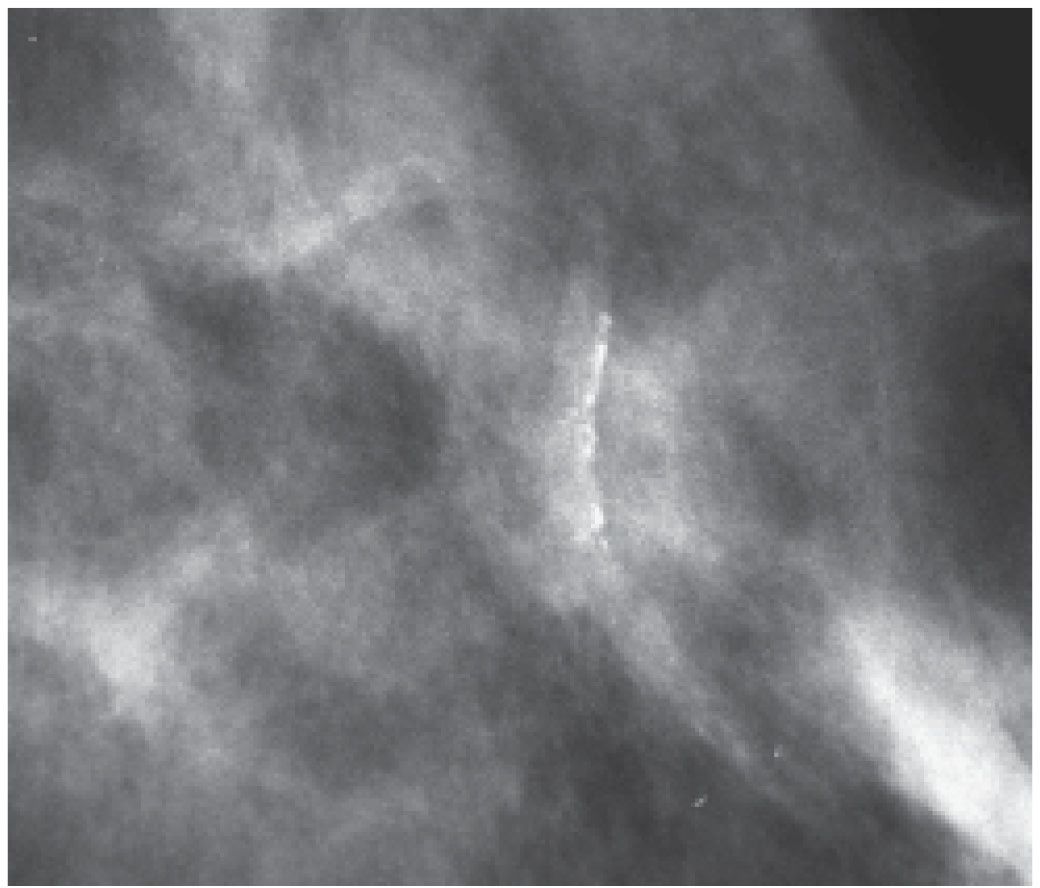

Deposition of calcium in the media, at the perimeter of the elastic fibers of arterial walls, results in dense, linear, parallel, or “tram track-like” calcifications most common in postmenopausal women; in some patients, these develop and progress rapidly after menopause (if no hormone replacement therapy is used). When seen in younger premenopausal women, it is often in patients with diabetes (see Fig. 7.80) or in those with underlying renal disease. Interestingly, in some women this is a reversible process with vascular calcifications decreasing or resolving completely on subsequent screening mammograms (Fig. 6.11). When only a portion of the arterial wall is affected, or when small vessels are involved, the calcifications may be linear, irregular, variable in density, and have a linear orientation (Fig. 6.12A), simulating those occurring in DCIS. On careful inspection, early developing arterial calcifications often have a beaded appearance (Fig. 6.12B). Spot compression magnification views in some of these patients demonstrate the contralateral noncalcified vessel wall, noncalcified sections of the vessel coming into and out of the area of the calcifications, or an accompanying vein (Fig. 6.12A and 6.13).

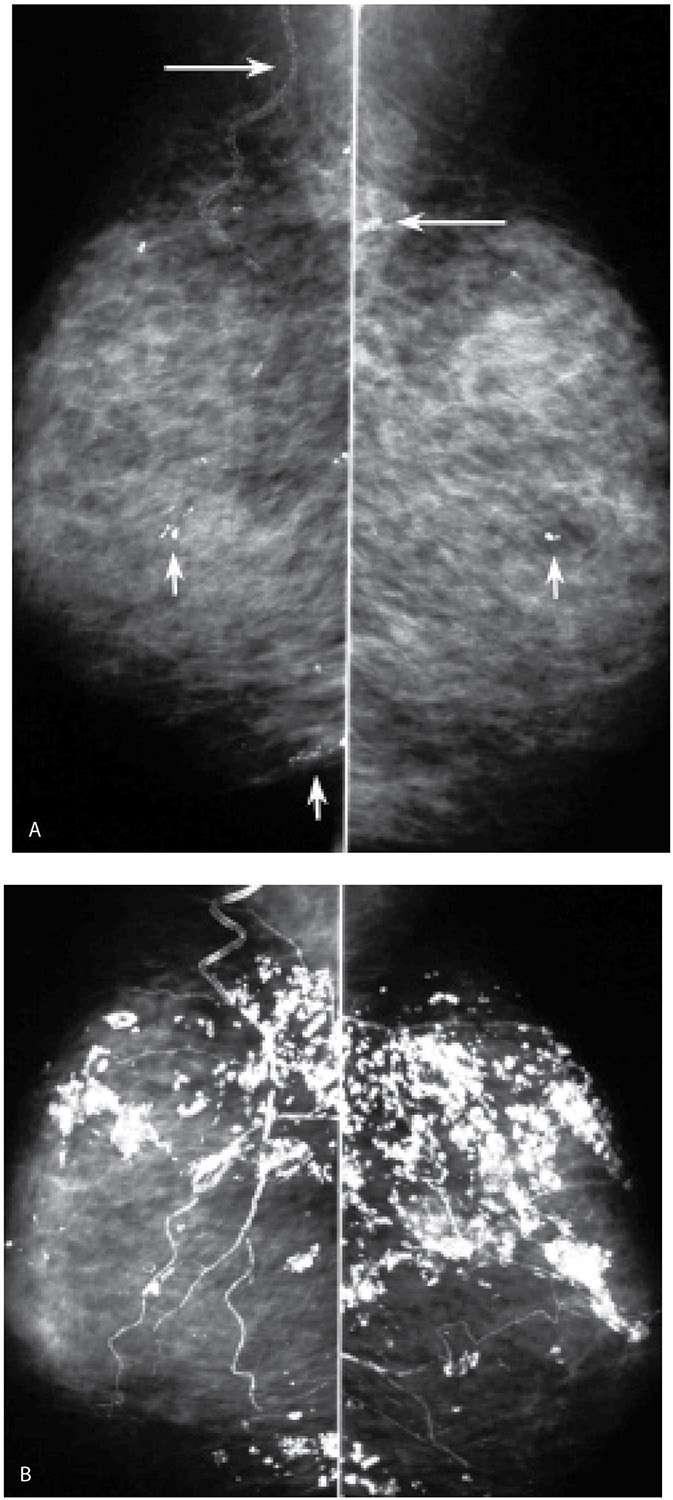

FIG. 6.11 • Resolving arterial calcifications. A: MLO views in a 63-year-old woman. The lateral thoracic arteries (long arrows) and some branches of the internal mammary arteries (short arrows) are densely calcified bilaterally. B: MLO views, 2 years after those in part A. Arterial calcifications are almost completely resolved. Although in this patient no apparent explanation for the resolution of the calcifications is known, in some patients, with underlying cardiac or renal disease, we have seen vascular calcifications resolve following cardiac or renal transplants; in some postmenopausal women, arterial calcifications may resolve after the patient is started on hormone replacement therapy.

FIG. 6.12 • Arterial calcifications, early stage. A: Fine linear calcifications in a linear distribution (long arrow) are noted. In this patient, a vessel (short arrows) is identified coming into and out of the area of the calcifications. BI-RADS 2: Benign finding. B: Linear calcifications with a beaded appearance and linear distribution. In this patient, multiple spot compression magnification views are done, and no association with a vessel is established. Biopsy is done with a sizeable hematoma developing after the first core. Core radiograph (not shown) demonstrates a linear calcification in the one core obtained. Calcification in the media of an artery is diagnosed histologically. It is exceedingly rare not to be able to correlate calcifications to a vessel wall on spot compression magnification views, but it does happen.

FIG. 6.13 • Vascular calcifications. In this patient, the association of linear calcifications with the wall of an artery is established easily on this projection. The contralateral vessel wall and other portions of the vessel are identified readily. BI-RADS 2: Benign finding. (From Cardeñosa G. Breast Imaging [The Core Curriculum Series]. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.)

FIG. 6.14 • Vascular calcifications. “Quirky” calcifications are identified with smooth margins and central lucencies consistent with arterial calcifications. Similarly, calcifications are noted diffusely scattered bilaterally. BI-RADS 2: Benign finding. (From Cardeñosa G. Breast Imaging [The Core Curriculum Series]. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.)

Occasionally, smaller vessels calcify, leading to the appearance of “quirky” types of calcifications. The borders of these calcifications are well defined, and a lucent center is often seen when evaluated closely with a magnifying lens (Fig. 6.14). In our experience, these smaller arterial calcifications tend to be more common in premenopausal women with dense tissue and can fluctuate from year to year; in some patients, they resolve completely. These patients do not usually have a history of diabetes or arteriosclerotic heart disease.

It has been reported by several investigators that there may be a correlation between the extent of arterial calcifications seen on a mammogram and underlying coronary artery disease (10–12). This remains controversial, with some reports refuting the correlation (13,14) particularly since calcifications and plaque in heart disease involve the intima of the vessel wall, not the media as seen in the vessels calcifying in the breast. We describe the presence of arterial calcifications in our consultation reports when they are identified in premenopausal women or when the calcifications develop rapidly from one year to the next (10–12). Rarely, tortuous and serpiginous calcification associated with a venous structure may be seen as long-term sequelae of Mondor disease (15).

STROMAL CALCIFICATIONS

Calcifications developing in the stroma of the breast are dystrophic. Since these develop in fibrous tissue, and not in predefined anatomic spaces, they vary in size, shape, and density; no two of these calcifications are alike. They are coarse, dense, large, irregularly shaped, and may have associated areas of lucency (Fig. 6.15). When diffuse and bilateral (Fig. 6.16), they may reflect the presence of an underlying inflammatory, degenerative, or metabolic process (e.g., renal disease with hyperparathyroidism). Dystrophic calcifications can also be seen in the fibrous capsule that forms around implants (Fig. 6.17; also see Fig. 11.49A, B), remnants of calcified capsule if implants are explanted (see Fig. 11.57C), or in conjunction with the granulomatous response elicited by foreign bodies such as silicone or paraffin injections.

FIG. 6.15 • Stromal (dystrophic) calcifications. Dense, coarse calcifications developing in fibrous tissue and not a predefined space are variable in size, density, and shape. They may be focal, limited to areas of prior surgery or trauma or diffuse. (From Cardeñosa G. Breast Imaging [The Core Curriculum Series]. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.)

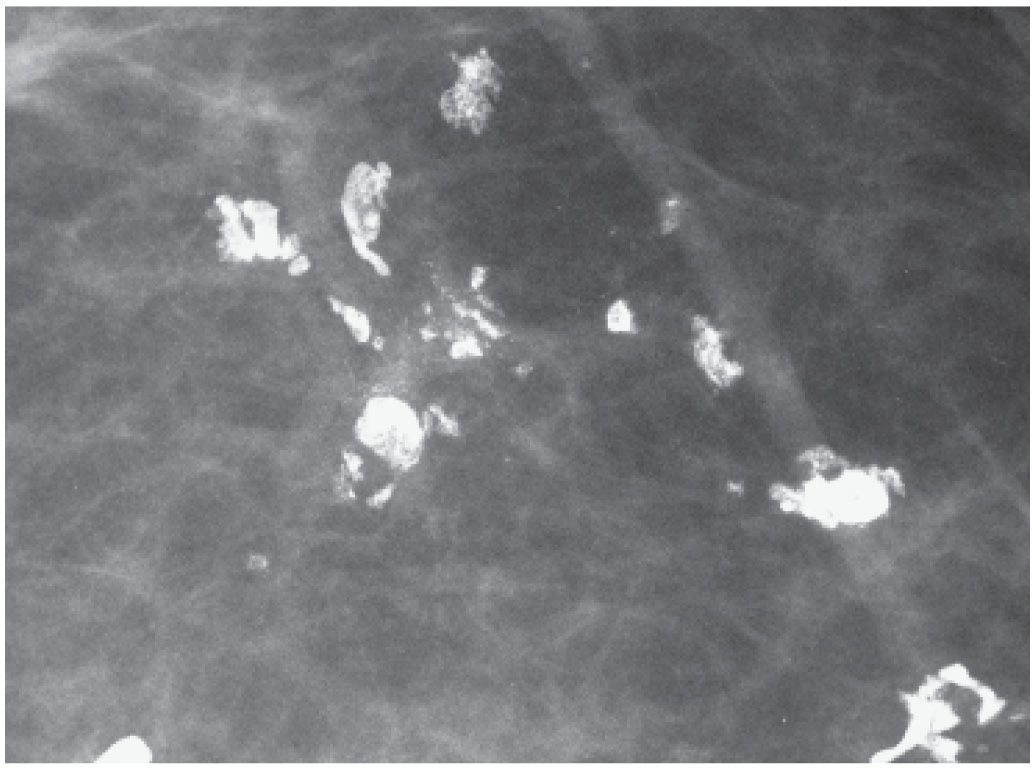

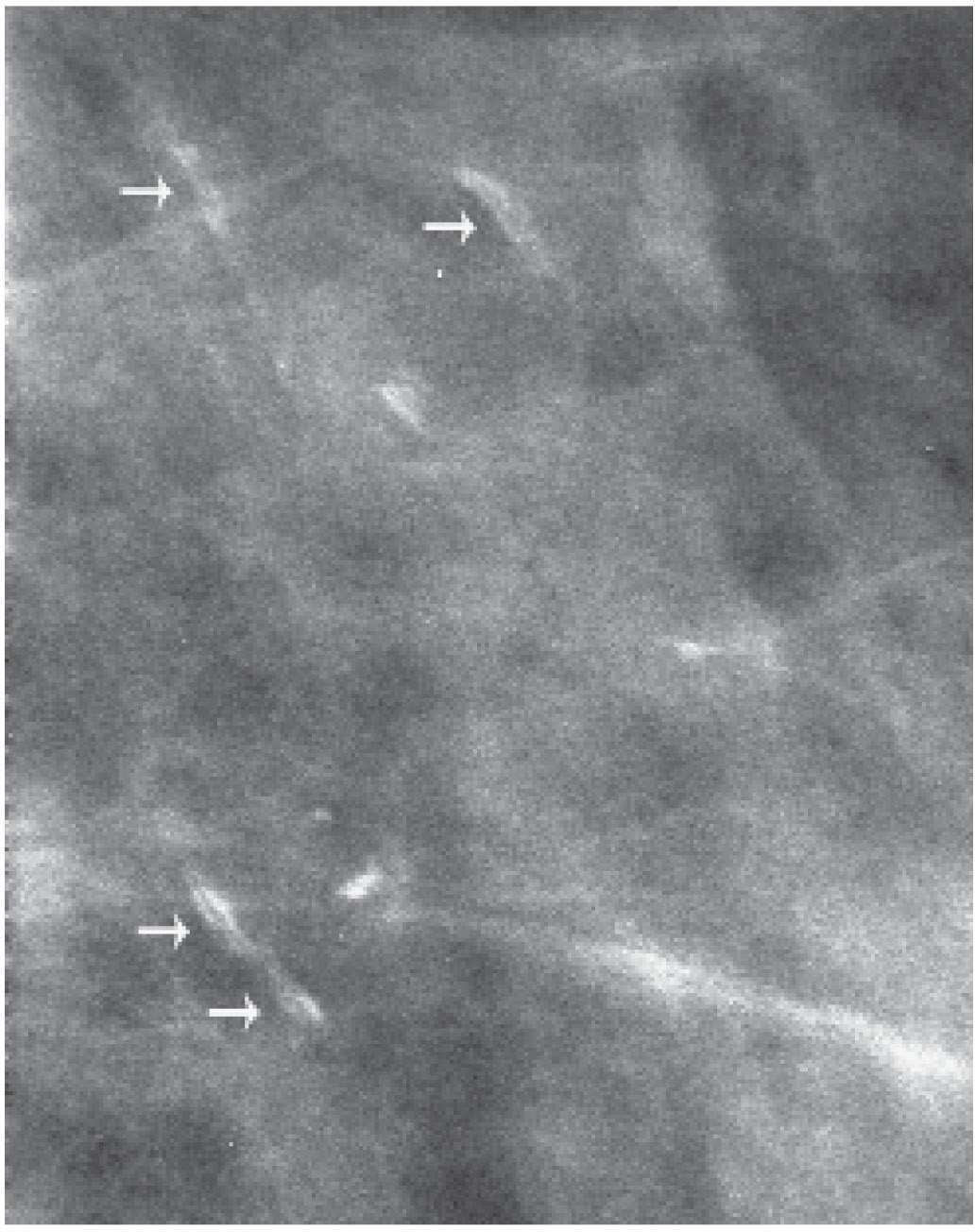

Dystrophic calcifications in areas of dense stromal fibrosis can demonstrate a linear appearance (Fig. 6.18). The margins are sometimes irregular and jagged with some of the calcifications forming acute angles. In a given cluster, some of the linear calcifications are well defined, and on close inspection central lucencies (Fig. 6.19) may be identified. Stromal or dystrophic type calcifications can also develop in the fibrous tissue in masses such as fibroadenomas (see discussion in mass section) and in areas of prior trauma, burns, surgery, or radiation therapy (see Chapter 11) as well as a healed abscess or hematoma.

DUCTAL

The precipitation of calcium salts in entrapped secretions in subsegmental ducts leads to the development of fusiform calcium casts of the dilated ducts (16,17). These calcifications (Figs. 6.1 and 6.20) are “rod-like,” cigar shaped, coarse, high in density, smooth bordered, diffuse, bilateral, pointing toward the nipple, and can demonstrate branching. When the calcifications form periductally, a radiolucent center is seen. This type of calcification reflects the presence of duct ectasia with associated inflammatory changes also called periductal mastitis, secretory disease, comedo mastitis, plasma cell mastitis, and mastitis obliterans. Histologically, the dilated ducts contain amorphous debris, foam cells, and, less commonly, a crystalline-like lipid material. The epithelial cells normally lining the ducts are atrophic, appearing attenuated, deformed, and flattened or absent. The elastic tissue layer is disrupted and partially destroyed. In women with mastitis obliterans, fibrous tissue obliterates the epithelial lining and duct lumen. A chronic inflammatory process composed of plasma cells may be seen periductally.

This process is often diffuse and bilateral, less commonly unilateral, and rarely focal (Fig. 6.21). Since the epithelial lining of the ducts is flattened or denuded, the border of these calcifications is smooth (Fig. 6.22). Coarse calcifications, associated with dense fibrotic breast tissue in the subareolar areas, reflect burned out plasma cell mastitis. These patients may describe a tender mass in one or both subareolar areas. A white, thick, cheese-like, and at times foul-smelling discharge may also be present arising from multiple duct openings bilaterally.

FIG. 6.16 • Stromal (dystrophic) calcifications developing in a patient with end-stage renal disease and hyperparathyroidism. A: MLO views. Dense tissue. A few coarse dense calcifications (short arrows) are present scattered bilaterally as are arterial calcifications (long arrows). B: Follow-up MLO views. The patient has developed many dense, coarse stromal (dystrophic) calcifications reflective of her end-stage renal disease and hyperparathyroidism. Dense arterial calcifications are now also apparent. In these patients, the dystrophic (stromal) and arterial calcifications can resolve completely if the renal disease (and hyperparathyroidism) are well controlled with dialysis or renal transplantation.

FIG. 6.17 • Calcification in fibrous capsule around implant. Implant displaced views. In some patients, dense dystrophic calcifications can be seen in the fibrous capsule that forms around implants and may remain after explantation (see Fig. 11.57C).

LOBULAR

Lobules represent groupings of round glands called acini. It is in the acinar structures that milk is produced during late pregnancy and lactation. If the acini are not altered by proliferations of the surrounding fibrous perilobular tissue, as is seen in fibroadenomas and sclerosing adenosis, calcifications developing in acini are round, relatively high density, well defined, or pearl-like and smooth bordered. If the lumen of the glands is small, the calcifications may be punctate. These can occur as clusters (Fig. 6.23A, B) of predominantly round calcifications or diffusely scattered round calcifications often bilaterally (Fig. 6.23C, D). When there is associated proliferation of perilobular stroma, as is seen with sclerosing adenosis and fibroadenomas, the acinar spaces may be deformed, compressed, and elongated, resulting in grouped pleomorphic calcifications that are indistinguishable from those seen in some forms of DCIS (18).

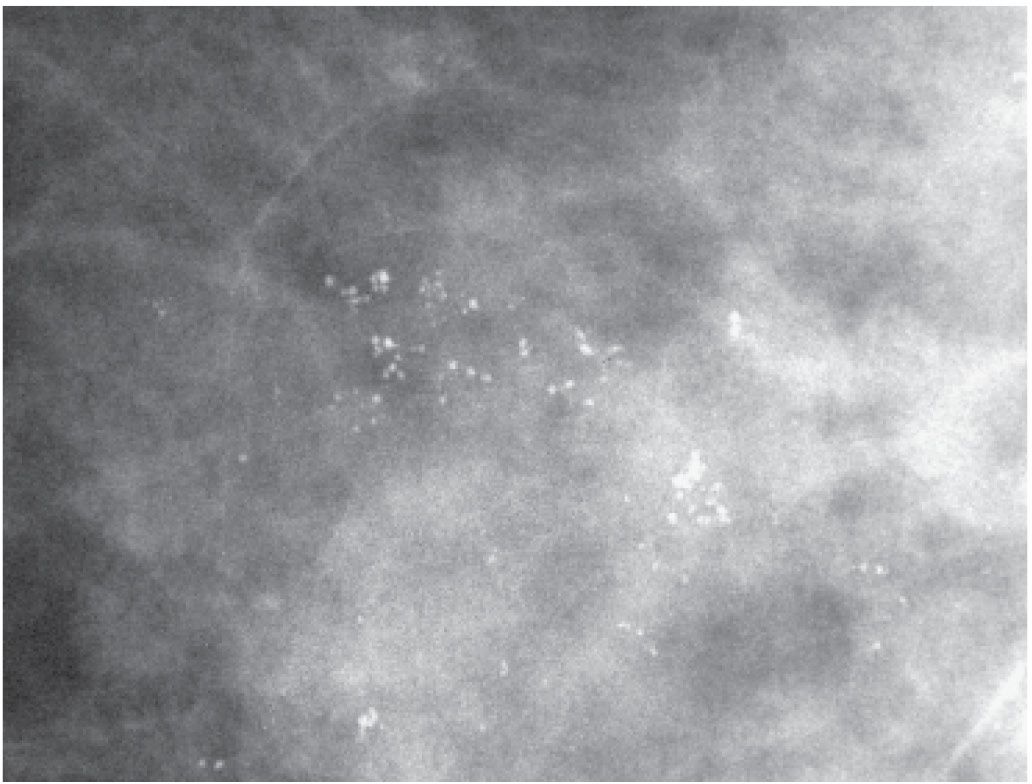

If the acinar spaces are tiny and tightly apposed, we may not be able to resolve the individual calcification particles but rather see smudgy, ill-defined, or amorphous calcifications. When specimen radiography is done using higher magnification factors than achievable in patients, these amorphous calcification clusters can sometimes be resolved into individual punctate calcifications reflecting tightly packed, adjacent acinar structures. Amorphous calcifications (5) usually reflect the presence of sclerosing adenosis; they can be associated with DCIS, commonly low nuclear grade without central necrosis (Table 6.5). When the amorphous calcifications are diffuse and bilateral in patients with dense tissue (Fig. 6.24), our approach is careful follow-up. When amorphous calcifications are identified grouped (Fig. 6.25), particularly if developing compared with prior studies, or if in an unusual location (e.g., upper inner quadrant), we recommend biopsy.

FIG. 6.18 • Stromal (dystrophic) calcifications in hyalinized breast tissue. Spot compression magnification views in the MLO (A) and CC (B) projections. Linear calcifications in a linear orientation are identified. On careful review with a magnification lens, some have a central lucency (arrows). Although the diagnosis of stromal fibrosis is suspected on the basis of the mammographic appearance of the calcifications, a biopsy is done confirming the diagnosis of dense stromal fibrosis with calcifications. BI-RADS 4A: Suspicious abnormality, biopsy is indicated. On the MLO view, arterial calcifications are also present. (From Cardeñosa G. Breast Imaging [The Core Curriculum Series]. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.)

BENIGN-TYPE CALCIFICATIONS DEVELOPING IN MASSES

Curvilinear calcifications can be seen when they form in the wall of a mass, possibly a cyst (Fig. 6.26A), oil cyst (Fig. 6.26B), or in silicone granulomas (Fig. 6.27). Some of these are lucent-centered calcifications (Fig. 6.28) or, rim-type calcifications (Fig. 6.29) (e.g., when developing in the wall of an oil cyst).

Calcium can be present in suspension (Fig. 6.30) or as discrete calcifications in micro- or macrocysts (Fig. 6.31). The hallmark of intracystic calcifications is their variation in appearance on orthogonal views (19–21). When viewed on the CC view, the calcium may appear as an amorphous, ill-defined, round smudge, or a cluster of high-density tightly packed round (polyhedral) calcifications. When viewed in the horizontal plane on a 90-degree lateral view (and often even on the MLO view), the calcium layers in the dependent portion of the cyst and is seen as sharp, high-density curvilinear calcification or individual calcifications assuming a “teacup” or a meniscus-like configuration, enabling definitive diagnosis (Fig. 6.32). Microcysts and milk of calcium can be multifocal and bilateral in women with dense tissue (Fig. 6.30), or focal and unilateral (Fig. 6.32). In some patients, milk of calcium involves macrocysts (Fig. 6.31). Although ultrasound evaluation is not indicated in these patients, micro and macrocysts with associated milk of calcium can be identified on ultrasound (Fig. 6.30C).

FIG. 6.19 • Stromal calcifications. Spot compression magnification view demonstrating linear calcifications with a central lucency (arrows). BI-RADS 2: Benign finding. Calcifications are stable on subsequent annual screening mammograms. (From Cardeñosa G. Breast Imaging [The Core Curriculum Series]. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.)

In solid masses, calcifications can develop in epithelial elements, stromal components, or peripherally. Popcorn-type calcifications (Fig. 6.33A) are dystrophic, developing in the hyalinized fibrous stroma of fibroadenomas; in some patients with a papilloma, a “hollow” popcorn is seen as the periphery of the lesion calcifies (Fig. 6.33B; also see Fig. 9.34C). Popcorn calcifications are dense and coarse and can occur in one or both breasts and be uni- or multifocal. In the initial stages of hyalinization with calcification, grouped pleomorphic calcifications may be seen with or without an associated mass (Fig. 6.34). Sequential mammograms demonstrate progressive deposition of calcium with coalescence and formation of larger calcifications (Fig. 6.35). Some women with calcified fibroadenomas present describing a hard “lump.” In these patients, it is imperative that the interpreting radiologist be unequivocal in their description of the benign finding and its correlation with the palpable finding. To mitigate surgical referrals and potentially unnecessary biopsies, the patient and referring physician must be assured that the benign finding correlates with the palpable finding. A subgroup of calcifications occurring in fibroadenomas is fairly distinctive. These calcifications are high-density, “chunky,” “coral-like” with jagged edges, some of which form acute angles (Fig. 6.36).

FIG. 6.20 • Ductal, rod-like calcifications. A: CC view demonstrating a few rod-like calcifications scattered in the right breast. B: CC view 2 years later. Many more dense rod-like calcifications have developed, and the preexisting calcifications are larger and denser. This type of calcification develops bilaterally, some have branch points, and most point toward the nipple. Grouped dystrophic calcifications (arrow) are now also noted medially. In these patients, it is easy to be mesmerized by the obviously benign findings. Force yourself to look away and search for the subtleties of a possible cancer among the obviously benign. (From Cardeñosa G. Breast Imaging [The Core Curriculum Series]. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.)

FIG. 6.21 • Focal rod-like calcifications. What is typically a diffuse bilateral process may be focal in some patients. The calcifications are dense, smooth bordered, and no other calcifications are identified in the surrounding tissue. If you have any questions regarding the underlying etiology in these patients, a 6-month follow-up may be helpful in assuring you are not dealing with an atypical presentation of DCIS with central necrosis. BI-RADS 2: Benign finding. (From Cardeñosa G. Breast Imaging [The Core Curriculum Series]. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.)

SUTURES

Suture material in the breast can calcify (22,23). These calcifications may be evenly spaced, linear, or curvilinear with smooth borders localized to lumpectomy sites (Fig. 6.37); in some, knots may be apparent. These calcifications appear to be a rare occurrence in the nonirradiated breast. They occur with a higher frequency in women following lumpectomy and radiation therapy. It has been postulated that radiation-induced damage and alterations in tissue healing delay the reabsorption of catgut sutures, thereby providing a matrix for the deposition of calcium (23).

FIG. 6.22 • Ductal, rod-like calcifications. Coarse, dense calcifications with smooth borders reflect the attenuated or denuded epithelial lining of the ducts. Branch points may be seen (long arrow). Central lucency (short arrow) is noted when the calcifications form periductally. BI-RADS 2: Benign finding. (From Cardeñosa G. Breast Imaging [The Core Curriculum Series]. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.)

FIG. 6.23 • Lobular calcifications. A: Grouped monomorphic, round high-density calcifications. (From Cardeñosa G. Breast Imaging [The Core Curriculum Series]. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.) B: Loosely grouped round, high-density calcifications. C: Round (monomorphic) calcifications are identified diffusely scattered in the dense parenchyma. D: MLO views photographically coned to the superior aspect of the image. Round and punctate calcifications are present diffusely scattered bilaterally more in the right breast compared with the left. Again, don’t be mesmerized by the obviously benign. Look carefully among the benign for possible significant findings. BI-RADS 2: Benign finding.

PARASITES

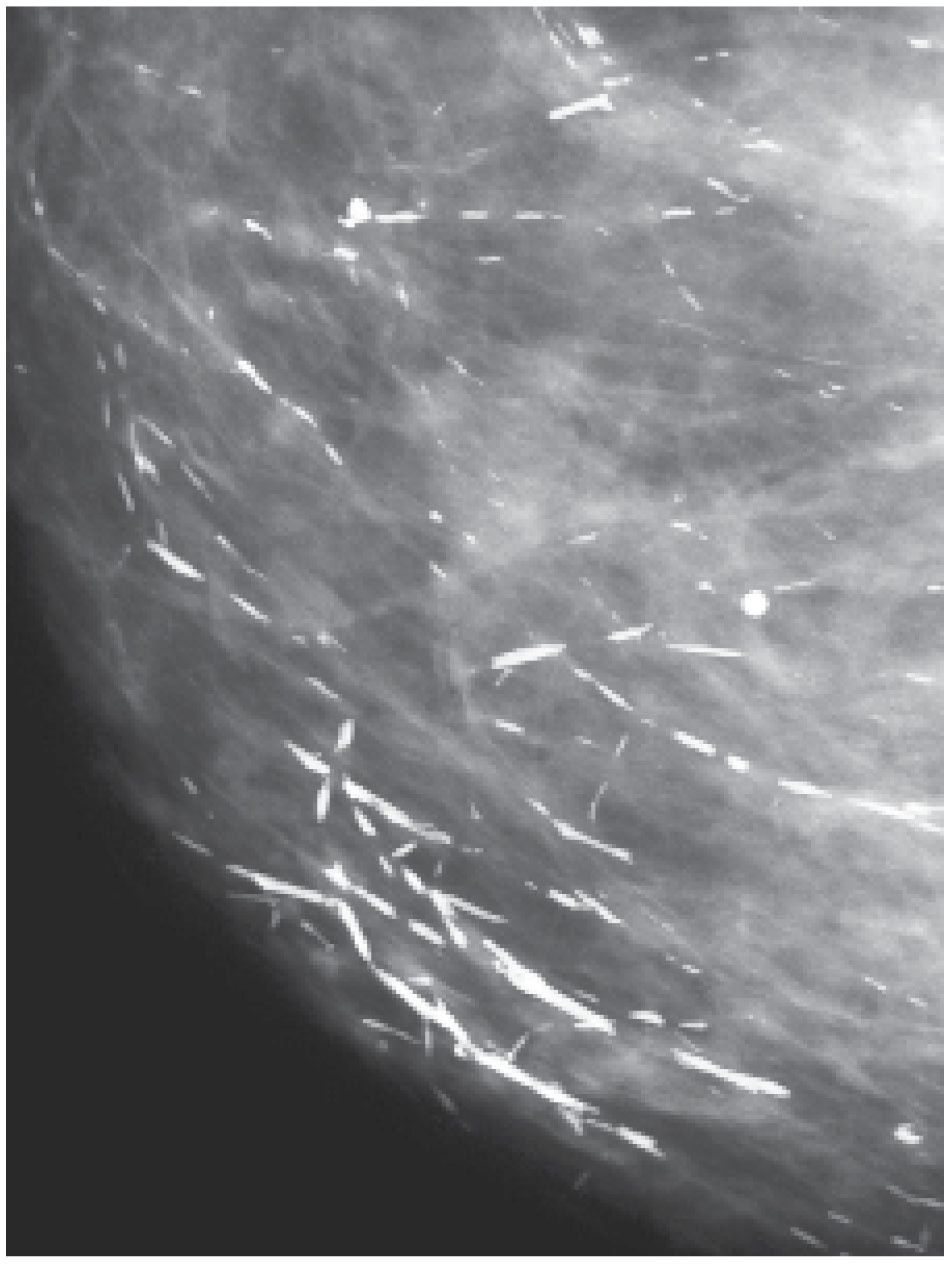

Sporadic case reports are available describing the imaging features of parasites localized to the breast. These include filariasis (Wuchereria bancrofti and Brugia malayi), onchocerciasis (Onchocerca volvulus), and loiasis (Loa loa), all of which tend to be localized to the subcutaneous tissues, cysticercosis, dracunculosis, and schistosomiasis (24,25). The dead parasites calcify, leading to the development of linear, curvilinear, coiled, lace-like, bead-like, or serpiginous calcifications (Fig. 6.38) in isolation or with an associated soft tissue component (as has been reported for cutaneous myiasis—Dermatobia hominis) (26). Trichinosis (Trichinella spiralis) involves the pectoral muscles and spares breast tissue (27); fine, monomorphic “pearl-like,” punctate calcifications are noted diffusely scattered but limited to the pectoral muscles (Fig. 6.39).

CALCIFICATIONS ASSOCIATED WITH MALIGNANCY

When considering calcifications associated with malignancy, we are primarily talking about proliferative cellular processes occurring in terminal ducts. Ductal carcinoma in situ is cancer arising in the terminal duct lobular units; it is a noninvasive or intraductal disease and should be distinguished from invasive breast cancer. The most common mammographic manifestation of DCIS is calcifications detected in otherwise asymptomatic patients during screening. Rarely, DCIS can present (Table 6.6) as a macrolobulated or spiculated mass (see Figs. 8.20 and 8.21), an area of distortion detected mammographically (see Fig. 8.22), a palpable mass, parenchymal asymmetry (see Figs. 9.27 and 9.28), diffuse parenchymal change (see Figs. 9.20 and 9.21), developing ductal distension (see Figs. 5.38, 9.35, and 9.36), spontaneous nipple discharge (clear, serous or bloody), or Paget disease (see Fig. 9.30) of the nipple (28,29). With the increasing use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), mammographically and clinically occult DCIS is being diagnosed following the detection of segmentally distributed, non–mass-like, clumped and linear enhancement (see Fig. 5.38). Currently, MRI may, in fact, be the best method available for detecting DCIS. Additionally, the extent of disease in many patients with mammographically detected DCIS is more accurately demonstrated with MRI (see Fig. 3.16). An increasing number of studies suggest that MRI is more sensitive in detecting and characterizing the extent of DCIS than mammography (30–32).

Table 6.5 DIFFERENTIAL: AMORPHOUS (“SMUDGY”) CALCIFICATIONS

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree