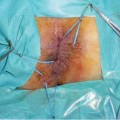

Fig. 8.1

CT from one of the three cases of colorectal cancer complicating perianal Crohn’s disease seen in our department during the last decade. a Circumferential stratified thickening of the rectal wall; b levator ani muscle involved in the abscess; c ischiorectal abscess and fistula with seton drainage

8.2 Diagnosis

When malignant transformation of a perianal fistula is suspected, the diagnostic approach is not different from the normal workup for complicated perianal disease as proposed in the Guidelines of the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organitazation [13]. Examination under anesthesia (EUA) is considered to be the most sensitive diagnostic tool, with an accuracy of 90% in the hands of an experienced surgeon. It allows concomitant surgery, such as abscess drainage, anal stenosis dilation, and seton placement [14]. Furthermore, a complete set of biopsies can be obtained. Pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has anaccuracy of 76-100% compared to EUA and may provide additional information [14]. Anorectal ultrasound has an accuracy of 56-100%, especially when performed by experts in conjunction with hydrogen peroxide enhancement [15, 16]. The best performance in terms of accuracy is obtained by the combination of EUA with one of the two imaging procedures.

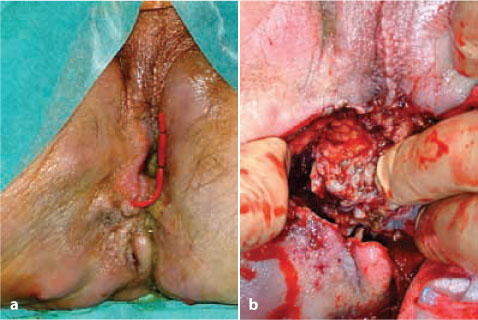

After a diagnosis of CRC is achieved, a complete colonoscopy must be performed in order to assess the presence and extension of mucosal inflammation and to exclude synchronous colonic lesions. According to the guidelines of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN version 2.2012), both a total-body computed tomography (CT) scan and measurement of preoperative CEA levels are needed. If the histology is diagnostic of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), the workup has to be completed with a fine-needle aspiration biopsy of the suspected inguinal lymph nodes, HIV testing, a gynecological exam to exclude cervical cancer, and, in selected cases, positron emission tomography-CT scan. When the patient has extended jejuno-ileal and/or colonic CD, a complete evaluation of the location and behavior of the inflammatory lesions is mandatory due to the critical implications in therapeutic strategy (see 8.3 Treatment). The same preoperative CT scan for cancer staging is in many cases also useful for CD re-staging, providing the appropriate adjustments are made (e.g., entero-CT scan of the abdomen). Unfortunately, detection of cancer at the first visit followed by biopsy confirmation occurs in less than 20% of the cases. Thomas et al., in a recent review of the literature, reported delays in the diagnosis of adenocarcinoma and SCC (non-human- papillomavirus type 16 correlated) of 6.2 and 5.4 months, respectively [17]. Adenocarcinoma is the most common cancer type (60-70%) (Fig. 8.2). At the time of diagnosis, affected women are younger (47 vs. 53 years), have a shorter disease duration (18 vs. 24 years), and a shorter history of perianal disease (8.3 vs. 16 years) than is the case in affected men [17].

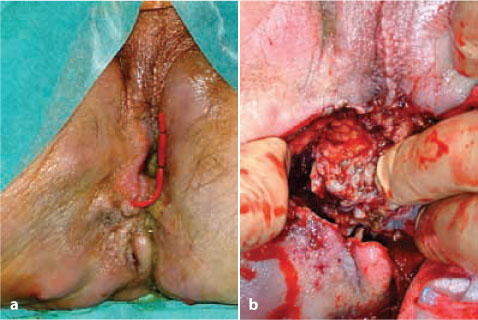

Fig. 8.2

a Clinical presentation of a patient’s perineum, showing scars from previous perianal disease, a seton drainage in place, and recurrent fistula and abscess. b Adenocarcinoma arising from the perianal fistula invading soft tissues and muscles of the right perineum

8.3 Treatment

Since a cancer complicating perianal disease in IBD is rare, the following indications for treatment are based only on anecdotal case reports and speculative considerations. A cancer originating in a perianal fistula, whether or not it has an intraluminal portion, spreads by definition outside the rectal wall, potentially involving soft tissues, muscles, gynecological and urological structures, and even bones. Preoperative staging is difficult to standardize, but according to the different staging systems this kind of cancer is usually classified as T4b or Dukes D, with all the surgical and medical therapeutic implications. In Figures 8.1 and 8.2 are reported the CT scan and EUA findings of a patient with perianal adenocarcinoma extended to the extraluminal pelvic structures. However, in a patient with IBD who is diagnosed with cancer, two major considerations have to be made. On the one hand, these patients are almost always under treatment with immunosuppressive and/or biological therapy in order to control inflammation. These treatments have to be promptly stopped if ongoing and are absolutely contraindicated in the future. Nonetheless, the problem of maintaining the IBD in remission after surgery for cancer remains unresolved. On the other hand, during treatment with cytotoxic drugs, patients with IBDs will be at high risk of developing complications, such as severe diarrhea, luminal bleeding, enhanced toxic effects, and flare of the inflammation itself [18].

Furthermore, in IBD patients, no data are available regarding specific therapeutic indications for the underlying inflammatory disease during radio- and chemotherapy. Continuous-infusion 5-FU alone, in combination with either leucovorin or oxaliplatin (FOLFOX), seems to be tolerated best, while bolus infusions of 5-FU and combination therapy of irinotecan with 5-FU should be avoided because of severe diarrhea and the possibility of sepsis. Although it is theoretically possible that cetuximab could adversely alter IBD activity, clinical experience in CRC patients has not shown any significant gastrointestinal side effects. Bevacizumab, however, has been associated with rare episodes of intestinal perforation and should thus be used with extreme caution in patients who have IBD [18

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree