Vaginal Carcinoma

Epidemiology

Vaginal carcinoma is predominantly a disease of the postmenopausal woman, with most cases occurring after 60 years of age. It is an uncommon cancer, accounting for 1% to 3% of all gynecologic malignancies. Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common cell type, accounting for 80% to 90%, with adenocarcinoma accounting for the remainder ( Table 35-1 ). Vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VAIN) has association with human papillomavirus (HPV) and occurs in a younger age-group. Most patients with VAIN undergo successful treatment, and only a small percentage progress to invasive vaginal carcinoma. Unlike the strong association between cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cervical carcinoma, no such definite association has been established between VAIN and vaginal carcinoma. Other risk factors associated with vaginal carcinoma are pelvic radiation and chronic vaginal irritation. Most cancers resulting from radiation occur after treatment for cervical carcinoma. Cancers developing within 5 years of treatment are usually recurrence of cervical carcinoma, and those developing later are likely primary vaginal carcinomas. Clear cell carcinoma is a subtype of adenocarcinoma with a strong association with in utero exposure to diethylstilbestrol (DES) in the first trimester of pregnancy. This is a disease of younger women, with a peak incidence between 15 and 22 years. The overall incidence in the exposed female population is estimated at 1 in 1000. Because the cohort of women exposed to DES in utero is now beyond childbearing age, it is likely that few new cases of DES-related adenocarcinoma will be identified.

| Carcinoma Type | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Squamous cell | 85-90 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 5-10 |

| Melanoma | 3 |

| Sarcoma | 3 |

| Miscellaneous | 3 |

Signs and Symptoms

Painless vaginal bleeding is the most common symptom. This may be spontaneous postmenopausal or postcoital bleeding. Vaginal discharge and urinary frequency are less common presentations of the disease. Diagnosis is made by vaginal examination and biopsy.

Patterns of Spread

Vaginal cancer metastasizes by direct invasion and lymphatic and hematogenous spread. Direct invasion of the paravaginal tissues is more common than with cervical carcinoma because of the thin vaginal wall. Depending on the location of the cancer, there can be regional invasion of bladder, urethra, or rectum. The lymphatic spread from the upper half of the vagina is to the obturator, internal iliac, and later to paraaortic lymph nodes. Cancer arising from the lower half of the vagina spreads to the inguinal lymph nodes. Tumors from the posterior vaginal wall spread to superior and inferior gluteal nodes.

Staging of Vaginal Carcinoma

Staging is based on the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO). TNM and FIGO staging are displayed in Table 35-2 and Figure 35-1 .

| Primary Tumor (T) | ||

|---|---|---|

| TNM Categories | FIGO * Stages | |

| TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed | |

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumor | |

| Tis * | Carcinoma in situ (preinvasive carcinoma) | |

| T1 | I | Tumor confined to vagina |

| T2 | II | Tumor invades paravaginal tissues but not to pelvic wall |

| T3 | III | Tumor extends to pelvic wall † |

| T4 | IVA | Tumor invades mucosa of the bladder or rectum and/or extends beyond the true pelvis (bullous edema is not sufficient evidence to classify a tumor as T4) |

| Regional Lymph Nodes (N) | ||

| TNM Categories | FIGO Stages | |

| NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed | |

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis | |

| N1 | III | Pelvic or inguinal lymph node metastasis |

| Distant Metastasis (M) | ||

| TNM Categories | FIGO Stages | |

| M0 | No distant metastasis | |

| M1 | IVB | Distant metastasis |

* FIGO no longer includes stage 0 (Tis).

† Pelvic wall is defined as muscle, fascia, neurovascular structures, or skeletal portions of the bony pelvis. On rectal examination, there is no cancer-free space between the tumor and pelvic wall.

Role of Imaging in Staging of Vaginal Carcinoma

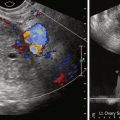

Staging of vaginal carcinoma by FIGO is based on clinical and physical examination, chest radiography, intravenous urogram, cystoscopy, and proctosigmoidoscopy. In the developed world, computed tomography (CT) scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have replaced the majority of these tests. Ultrasonography shows a soft tissue thickening of the vagina or an intraluminal mass with increased vascularity on color Doppler imaging. Ultrasonography is limited to assessment of the local extent of the tumor. MRI is excellent to assess the regional extent of the disease, and contrast-enhanced CT scan is useful for distant metastases. Positron emission tomography (PET)-CT has higher sensitivity and specificity than CT alone for lymph node and other metastases and is performed before radiation therapy.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Protocol

MRI is performed with either 1.5- or 3-Tesla systems using a phased array surface coil and standard malignancy protocol. Imaging with 3 Tesla has advantages of increased signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) but has decreased image homogeneity and increased susceptibility artifacts. After scout images, T2-weighted images of the pelvis are performed in three planes using either rapid acquisition with relaxation enhancement (RARE) or half-acquisition RARE pulse sequences. Fat-saturated RARE images may be of use after radiation treatment to identify high signal areas of residual disease. Before and after contrast-enhanced three-dimensional gradient echo images are obtained and presented in orthogonal planes. Imaging of the abdomen follows to assess for metastatic disease to the liver.

Imaging Findings

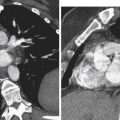

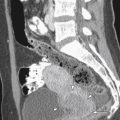

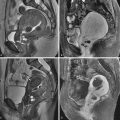

Vaginal cancer is of intermediate to hyperintense T2 signal intensity compared with the vaginal wall. In clinical stage T2 disease, the hyperintense tumor mass extends beyond the vaginal wall into the paravaginal tissues ( Figure 35-2 ), and in T3 stage it reaches the lateral pelvic wall. In clinical stage T4A, there is involvement of the urethra, bladder, and rectal mucosal surface ( Figure 35-3 ). Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted images show homogeneous or heterogeneous enhancement of the tumor with nonenhancing areas representing necrosis. T2-weighted images are also useful to assess size and location of lymph nodes (see Figure 35-3 , D ). Lymph nodes appear hyperintense compared with the hypointense iliac vessels, and metastasis is suspected when size exceeds 1 cm in the short axis. Unfortunately differentiation of enlarged metastatic nodes from reactive nodes cannot be made with certainty, and functional imaging such as PET-CT is often necessary to identify malignant involvement.

Differential Diagnosis From Other Vaginal Mass Lesions

Inflammatory Mass Lesions

Chronic granulomatous inflammations such as sarcoidosis and tuberculosis may involve the vagina with infiltration of perivaginal soft tissues similar to carcinoma ( Figure 35-4 ). Tuberculosis of the vagina is an uncommon form of genitourinary tuberculosis and is usually reported in immunosuppressed patients after HIV infection or organ transplantation. Sarcoidosis of the vagina is also uncommon, with few reports in the literature. There is usually other evidence of systemic disease, and diagnosis is established by biopsy.

Benign Neoplasms of the Vagina

Leiomyoma is a benign soft tissue mass with imaging characteristics similar to uterine leiomyoma ( Figure 35-5 ). These tumors can arise from any part of the vagina but more commonly from the midanterior vaginal wall. Fibroepithelial polyp, hemangioma, and neurofibroma are other less common benign mass lesions arising from the vaginal wall. They are all well defined and do not infiltrate into the perivaginal soft tissues.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree