- •

Locate the position of the mass within the heart.

- •

Search for multiple masses and identify the number of masses seen.

- •

Determine whether the mass is obstructing either right or left ventricular outflow.

- •

Determine whether the mass is obstructing right or left ventricular inflow across the tricuspid or mitral valves.

- •

Identify whether there is any distortion of the atrioventricular valve apparatus and presence/degree of atrioventricular valve regurgitation.

- •

Determine whether the mass is occupying ventricular cavity space and to what degree there may be limitation of ventricular filling.

- •

Look for heart rate irregularity that may reflect arrhythmia related to the mass.

Cardiac tumors are a relatively rare pathology seen in the fetus. Owing to the timing of ultrasound screening, the true incidence of tumors in utero is difficult to ascertain. Some tumors only increase in size over the course of the latter half of pregnancy, limiting detection in the second trimester when screening ultrasounds are typically performed. Most referrals for fetal echocardiograms are a result of detection of a mass, a pericardial effusion on screening ultrasound, arrhythmias, or family history of tuberous sclerosis. Unless the fetus has significant hemodynamic derangements or arrhythmias, they may not present for a fetal echocardiographic evaluation and may go undiagnosed until the neonatal period. Two cases of symptomatic neonates with cardiac tumors at birth were reported to have normal fetal echocardiograms at 26 and 38 weeks, respectively, demonstrating this point. One patient presented with fetal hydrops at term and was found to have a large left ventricular tumor infiltrating the right ventricle (RV) and atria; diagnosis of a fibroma was made after neonatal demise. The other neonate presented with supraventricular tachyarrhythmia (SVT), was electively delivered, and did well clinically after antiarrhythmic therapy. Postnatal echocardiography demonstrated a small right ventricular mass that was presumed to be a rhabdomyoma.

In a large multicenter study, cardiac tumors were diagnosed in 19 (0.14%) out of 14,000 fetal echocardiograms performed over an 8-year period. The gestational age at diagnosis ranged from 21 to 38 weeks, with rhabdomyoma occurring in the majority of fetuses along with a few cases of fibromas and hemangiomas. In a review of 10,000 fetal echocardiograms from a 12-year period, 11 cardiac tumors (0.1 %) (10 rhabdomyomas, 1 intrapericardial teratoma) were diagnosed in fetuses with gestational ages ranging from 20 to 34 weeks. In a summary of 91 fetal and newborn cases from the literature, rhabdomyoma was the most common tumor accounting for 50% of the cases, followed by teratoma (21%), fibroma (12%), myxoma (8%), and hemangioma (4%) along with the rare occurrence of the malignant tumors rhabdomyosarcoma (3%) and fibrolipoma (1%).

At the Fetal Heart Program at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia during an 8-year period between 2000 and 2008, there were 17 fetal diagnoses of cardiac tumors. Most of the tumors were solitary (13/17) and were either rhabdomyomas, fibromas, or pericardial teratoma based on the echocardiographic features. Multiple tumors were found in 4 cases consistent with the diagnosis of rhabdomyoma.

In some cases, cardiac neoplasms in the fetus may be the first indication of a genetic disorder including tuberous sclerosis, neurofibromatosis, Gorlin’s syndrome (nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome), familial myxomas, and Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome. Although the majority of tumors in the fetus and neonate are histologically benign, their size and location can cause pericardial effusions, compromised blood flow, arrhythmias, myocardial dysfunction, or hydrops fetalis ultimately leading to in utero demise.

Conservative management is the usual approach for fetuses without arrhythmias or hemodynamic compromise. Depending on the gestational age, fetuses with recalcitrant arrhythmias, increasing pericardial effusions, or significant hemodynamic compromise are delivered with anticipation for cardiac surgery to resect the tumor or tumors if technically feasible. Although fetal intervention has been reported for pericardial teratomas, currently, there are no options for prenatal therapy for fetuses with rhabdomyomas and fibromas. Fetal pericardiocentesis was performed in a 28-week fetus with an intrapericardial teratoma after the tumor was noted to be increasing in size with development of pericardial effusion along with concern for progression to hydrops. Although the effusion reaccumulated and hydrops developed at 33 weeks, lung maturity was documented and the patient was delivered at 34 weeks. The patient was immediately taken to surgery for resection of the tumor and did well clinically.

The natural history of cardiac tumors varies depending on their histological composition and anatomical location. Anatomy, pathophysiology, intervention, and clinical outcome are described in the following sections for each individual type of tumor.

Rhabdomyoma

Anatomy and Anatomical Associations

Rhabdomyomas are found most often within the ventricular wall and septum, subepicardial region, and atria and can be single or multiple in nature. Typically, these tumors are not associated with congenital heart lesions, although sporadic cases of rhabdomyoma associated with endocardial fibroelastosis, tetralogy of Fallot, and hypoplastic left heart syndrome have been reported.

Frequency, Genetics, and Development

Rhabdomyomas are the most common cardiac tumor seen in fetuses, infants, and children. In multiple fetal studies, rhabdomyomas were the predominant lesion ranging from 50% to 91% of the cases. A summary of 91 fetal cardiac tumor cases reported in the literature found 50% of these cases to be rhabdomyomas.

Rhabdomyomas or hamartomas are considered to be overgrowths of cardiac muscle with only mildly abnormal changes and without true neoplasia. Grossly, these single or multiple tumors are composed of white to yellow-tan circumscribed nodules in the myocardium, primarily in the ventricular wall or septum or subepicardial region of the atria.

Cardiac rhabdomyomas, particularly when there are multiple tumors, have been shown to be the earliest marker of tuberous sclerosis in utero. Tuberous sclerosis is an autosomal dominant disorder with variable expression and penetrance. It effects multiple organs and can result in neurological manifestations including developmental delay and seizures in early childhood. Hamartomas can occur in the skin, eyes, kidney, heart, and brain with the most clinically significant morbidity being the neurological manifestations that may not be present until early childhood. Several small studies have reported the diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis in fetuses or neonates with cardiac rhabdomyomas. In one study, 9/11 (81.1%) cases of rhabdomyoma were diagnosed with tuberous sclerosis. In follow-up of patients diagnosed with fetal rhabdomyoma, 15/19 (79%) were diagnosed with tuberous sclerosis. Of these cases with documented tuberous sclerosis, 5 had a fetal brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study suggestive of the disease. In a meta-analysis of 138 cases of prenatal diagnosis of cardiac rhabdomyoma, tuberous sclerosis was present in 85/133 (64%) cases, with multiple tumors being predictive of the disease. Although some studies have shown that multiple rhabdomyomas are predictive of tuberous sclerosis, it is unclear whether the same is true for single tumors. Because of the significant neurological manifestations that present later in childhood and the limited data available at this time regarding the association of the disease with single rhabdomyomas, fetal diagnosis of a cardiac rhabdomyoma typically leads to further evaluation for tuberous sclerosis. We typically perform fetal MRIs looking for hamartomas in the brain and/or kidneys that contribute to confirmation of the diagnosis. However, it is also known that many of these brain lesions develop after birth, so a clean MRI with no findings, unfortunately, does not rule out the possibility of tuberous sclerosis. In familial cases, molecular testing for mutations in tumor suppressor genes TSC1 or TSC2 may be useful because these genes have been implicated in tuberous sclerosis. Genetic testing is less helpful in confirmation of tuberous sclerosis in cases without a family history because there is a high likelihood of de novo mutation reportedly as high as 60% to -80%. Although sporadic mutations occur with high frequency, fetal diagnosis of a rhabdomyoma with an unknown family history should lead to further evaluation for the disease in parents and siblings.

Prenatal Physiology

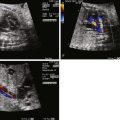

Cardiac rhabdomyomas have been detected as early as 18 weeks by fetal echocardiograms. These tumors have distinct echocardiographic features: highly echogenic, well circumscribed, intramural, or intracavitary nodules that sometimes are pedunculated with a homogenous, echo-bright, finely speckled pattern. Dystrophic calcification of the fetal myocardium can have similar appearances by ultrasound. In half of the cases, these tumors are asymptomatic and discovered only on routine ultrasonography, whereas the other half present secondary to arrhythmias or outflow tract obstruction.

Fetal arrhythmias, either tachyarrhythmias or bradycardias, have been reported in fetuses with rhabdomyomas. Left uncontrolled, these can lead to myocardial dysfunction and hydrops. Depending on the location and size of the tumor, there may also be a spectrum of hemodynamic effects ranging from being asymptomatic to poor cardiac output or elevation of venous pressures leading to hydrops.

Prenatal Management

Prenatally, limited interventions are available for the fetus with a rhabdomyoma. If the patient develops an arrhythmia such as SVT, drug therapies such as digoxin and sotalol potentially can help control the rapid rate by treating the mother with medication. If the patient develops hemodynamic compromise such as low cardiac output or hydrops as a result of obstruction, the only option, depending on gestational age, is early delivery. Close follow-up is essential because these tumors may remain stable or increase in size during the course of pregnancy. Therefore, it is important to perform sequential echocardiograms to monitor the tumor size and hemodynamic changes that may develop.

Postnatal Physiology

Just as described in the fetus, the impact of cardiac tumors on hemodynamics during the neonatal period depends on the location and size of the tumor. Large tumors can cause significant hemodynamic instability leading to the neonate who is critically ill with respiratory distress, congestive heart failure, and low cardiac output. Large rhabdomyomas that are located on the left side of the heart can cause inflow and left ventricular outflow tract obstruction and, if large enough, act as a space-occupying lesion essentially mimicking anomalies such as hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Those on the right side of the heart can cause inflow or right ventricular outflow tract obstruction, resulting in signs and symptoms of right-sided failure and cyanosis, and can mimic lesions such as tricuspid atresia or critical valvar pulmonic stenosis. Neonates may also present with rhythm issues: sinus bradycardia, atrial and ventricular tachyarrhythmias, or first- to third-degree heart block.

Postnatal Management

If the neonate is completely asymptomatic, the approach is to follow conservatively because most rhabdomyomas regress over time. In contrast, surgical intervention may be necessary if there is compromise of the cardiac output secondary to inflow or outflow obstruction. If there is significant right ventricular or left ventricular outflow tract obstruction, the patient should be started on prostaglandin E1 (PGE 1 ) infusion. Medical management for heart failure with dopamine and milrinone may need to be initiated to stabilize those who have low cardiac output and poor perfusion. If arrhythmias are contributing to cardiac instability, antiarrhythmic therapy should be added to the treatment regimen.

Outcomes

Rhabdomyomas generally have a favorable outcome with survival for fetuses ranging from 94% to 100%. In a meta-analysis of 138 rhabdomyoma cases summarized from the literature, large cardiac tumor size, fetal dysrhythmias, and hydrops were found to be predictors of a poor prenatal outcome. In another prenatal series, 6/9 fetuses had increase tumor growth up until 30 to 32 weeks’ gestation without hemodynamic compromise. In the neonatal period, no patient required medical therapy for arrhythmias or cardiac surgery. Median follow-up was 4.2 years and there was at least partial regression of the tumor. Tuberous sclerosis was diagnosed in 6/9 (67%) cases, with some patients requiring neurosurgery whereas others had neurological symptoms.

In another series of 19 fetuses diagnosed with rhabdomyomas, there was one spontaneous in utero demise at 28 weeks. There was no hemodynamic compromise in the others during the course of the pregnancy. During the neonatal period, 7/19 had cardiac symptoms requiring medical therapy or surgical intervention. Tuberous sclerosis was diagnosed in 15/19 (79%) patients. Beyond the neonatal period in patients for whom clinical information was available, 10/16 were asymptomatic from a cardiovascular standpoint, and in 10/16, tumors spontaneously regressed. In 1 patient, there was substantial tumor growth in utero requiring surgical intervention in the neonatal period.

Teratoma

Anatomy and Anatomical Associations

Teratomas develop primarily from the pericardium and attach to roots of the pulmonary and aortic arteries. Depending upon their size, they can compress adjacent atria or ventricles. A large number of these tumors are located anteriorly and to the right of the heart, causing compression of the cardiac chambers, great vessels, or even the trachea. Occasionally, they occur within the atrium or ventricle. Of the 19 cases summarized from reports in the literature, 17 were intrapericardial with only 2 occurring within the heart, 1 in the right ventricle and the other in the interatrial and interventricular septum. There are no reported associations with other congenital heart lesions with this tumor.

Frequency, Genetics, and Development

Intrapericardial teratomas are rare cardiac tumors but are the second most common tumor diagnosed in fetuses and newborns. Grossly, these tumors have a smooth, lobulated surface comprising numerous loculated cysts lined with a variety of epithelia. There are typically intervening solid areas composed of mature or immature neuroglial tissue with thyroid, pancreas, smooth and skeletal muscle, and foci of cartilage and bone. Histologically, these tumors contain all three germ layers: endoderm, mesoderm, and ectoderm. To date, there have been no reports of associations with genetic syndromes and no etiology has been identified.

Prenatal Physiology

Teratomas are heterogeneous with cystic components and pericardial calcification, along with the common finding of pericardial effusions and sometimes pleural effusions. They have distinct findings on echocardiogram with cystic areas appearing echolucent and calcifications as echogenic foci. Review of 31 cases reported in the literature reveals that most present with pericardial effusions in the second and third trimesters with 77% of fetuses developing hydrops without intervention. At least in two reported cases, both with pericardial effusions, systolic function was maintained. In both cases, Doppler hemodynamics were normal upon initial evaluation, but in one of the cases a week later, there was an abnormal single peak inflow suggesting compromised filling of the ventricle along with a wave reversal in the ductus venosus and umbilical venous pulsations. These findings are consistent with elevated venous pressures secondary to obstruction from the mass and can come on quite rapidly. Although limited data are available, it appears that Doppler assessment may be useful in determining hemodynamic compromise with this potentially rapid-growing tumor.

Prenatal Management

Intrapericardial teratoma is the only tumor that is amenable to fetal intervention when hydrops and a large pericardial effusion are present. There are numerous reports of successful fetal pericardiocentesis. It has been suggested by one group that fetal pericardiocentesis is warranted when there is early hydrops with a large pericardial effusion and a small mass. If there is a large mass associated with a large effusion, fetal surgery with resection is likely more efficacious, because there is a low likelihood of having a substantial effect on improving cardiovascular hemodynamics with simple drainage of the pericardial fluid alone. If no hydrops is present, the patient can be followed closely.

Postnatal Physiology

As with all mass lesions, physiology will be variable depending on the location and size of the lesion. If there is a large pericardial effusion, this may need to be drained urgently at birth, if it is found to be causing tamponade symptoms. If the mass is causing significant cardiac compression, there may be cyanosis or low cardiac output necessitating urgent surgical intervention to remove the mass.

Postnatal Management

Some have suggested that a cesarean delivery should be planned because of the risk of cardiac compression during vaginal delivery and the high likelihood of early neonatal distress because the mass may impair the normal transitional physiology. Delivery at a tertiary care center with a neonatal intensive care unit, pediatric surgery, or pediatric cardiac team is important because most patients will require surgery at some point during the neonatal period.

Outcomes

Analysis of 31 fetal cases of intrapericardial teratoma in the literature revealed a survival rate of 58% after all underwent successful surgical intervention in the neonatal period. Long term, once the tumor is removed, these patients typically do well.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree