Chapter 8 Cardiotocographic interpretation: clinical scenarios

MECONIUM-STAINED AMNIOTIC FLUID

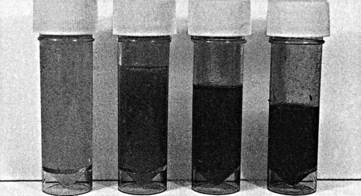

The incidence of meconium staining of the amniotic fluid increases steadily from 36 weeks to 42 weeks of gestation when it reaches in excess of 20%. This reflects maturation of the central nervous system and gastrointestinal tract manifested by increasing intestinal motility.77, 78 The passage of meconium by a preterm fetus is rare and characteristically associated with the unusual but lethal listerial infection.55 Fetal compromise, usually of an acute or subacute nature, also leads to the passage of meconium. Very acute stress such as placental abruption or umbilical cord prolapse paradoxically does not often lead to the passage of meconium. There are various degrees of meconium staining, ranging from diluted old meconium which is brownish-yellow to thick, green ‘pea soup’ meconium. Typically, thick undiluted meconium is seen in a breech presentation for mechanical reasons. Under these circumstances it is interpreted differently from the same appearance in a cephalic presentation. In a cephalic presentation the meconium has to find its way from the fetal anus near the fundus of the uterus to the cervix and vagina: it has to pass through the uterine cavity which is normally filled with a good volume of amniotic fluid; this is the fluid for dilution. If there is little fluid then the meconium cannot become diluted and remains thick. If there is a good volume of fluid a greater degree of wetness occurs after membrane rupture, with thinner meconium. When membrane rupture occurs several days after meconium passage then the meconium is thin and old. If there is no amniotic fluid on rupture of the membranes then concern may be justified on suspicion of oligohydramnios. Thick, fresh meconium in a cephalic presentation suggests oligohydramnios and if the trace is abnormal then delivery should be expedited unless it is expected without delay. In The National Maternity Hospital, Dublin, on every bedside on the labour ward there is a specimen of that woman’s amniotic fluid in a universal container. This focuses the attention on the issues involved (Fig. 8.1).

Clear amniotic fluid is reassuring.

Thick, fresh meconium in a situation of high risk is of great concern.

TWIN PREGNANCY

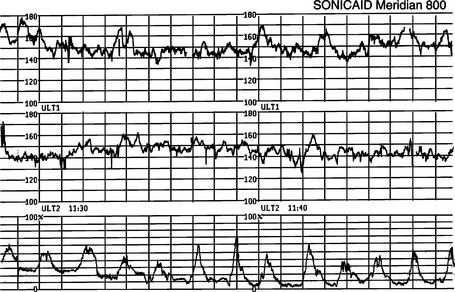

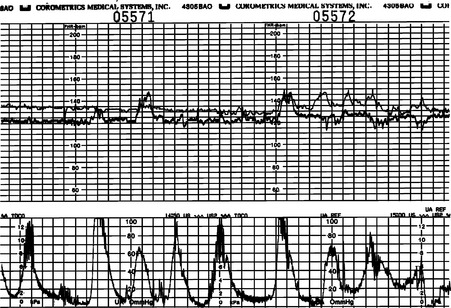

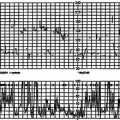

Perinatal mortality in multiple pregnancy is considerably higher than in singleton pregnancy, and particular risks are present during labour and delivery. It is now known that this mortality is considerably increased for monochorionic twins compared to their dichorionic counterparts. The rare monoamniotic twins should be delivered by caesarean section because of the risk of cord accidents, particularly after the delivery of the first twin. There is an increasing tendency to deliver monochorionic, diamniotic twins by caesarean section because of the risk of acute fetomaternal transfusion. If this is not done then very careful electronic monitoring must be undertaken. Twins are generally smaller than singletons, with more pathological growth restriction. The second twin may be at greater risk of this and the ability to electronically monitor both twins continuously is therefore important. The latest generation of fetal monitors have been specially designed to perform this function. One twin can be monitored on direct electrode with the other on ultrasound or both can be monitored using external ultrasound. To have only one machine at a woman’s bedside is a considerable advantage which should be fully exploited. The Sonicaid Meridian prints its own paper and therefore has the novel feature of a three channel trace (Fig. 8.2). The Hewlett-Packard and Corometrics models have a technique of printing out both traces in the same channel but in different shades (Fig. 8.3). It is critical to follow the second twin with the ultrasound transducer: this may prove difficult, especially in an obese mother. Assisted delivery is performed for the same indications as in a singleton pregnancy. A senior resident doctor must supervise the delivery of the second twin and ensure continuous electronic fetal monitoring during the interval between deliveries. Such an approach permits a more measured, less anxious delivery process; however, this should not be used as a justification for undue prolongation of the interval.

BREECH PRESENTATION

Babies presenting by the breech are acknowledged to be exposed to more risks than those presenting by the head. The Term Breech Trial Collaborative Group’s study has resulted in most breech babies being delivered by caesarean section.79 This is unfortunate as women who like to deliver vaginally are now being denied the opportunity of vaginal breech birth and doctors in training no longer have the opportunity to acquire this skill.

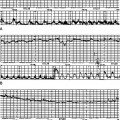

There are several risks, but intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) and umbilical cord compression have particular implications for fetal monitoring. The footling or flexed breech has a greater chance of cord prolapse and compression of the umbilical cord in labour. This is a classical scenario for variable decelerations due to cord compression as outlined in Chapter 4. This is one of the reasons why such cases usually have planned caesarean section. There is also evidence that compression of the skull above the orbits by the uterine fundus is a mechanism for variable decelerations. Figure 8.4

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree